Editor’s note: This article first appeared in The Cairo Review of Global Affairs.

The much-anticipated 18th Party Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in November unfolded according to that classic rhythm in the study of Chinese elite politics: predictability giving way to ambiguity, and optimism alternating with cynicism.

Prior to the announcement of the composition of the new guard, led by new party General Secretary Xi Jinping, many analysts both in China and abroad had believed that the new leadership would continue to maintain the roughly equal balance of power that existed between the Jiang Zemin camp and the Hu Jintao camp. Yet in the end, the results were a huge surprise: the Jiang camp won a landslide victory by obtaining six out of the seven seats on the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) while only one leader in the Hu camp—Li Keqiang, now designated to become premier in March—was able to keep a seat on this supreme decision-making body.

In the wake of the recent Bo Xilai scandal and the resulting crisis of CPC rule, many had anticipated that party leaders would adopt certain election mechanisms—what the Chinese authorities call “intra-party democracy”—to restore the party’s much-damaged legitimacy and to generate a sense that the new top leaders do indeed have an election-based new mandate to rule. For example, some analysts had anticipated that the CPC Central Committee might use competitive (though limited) multiple-candidate elections to select members of its leadership bodies, such as the twenty-five-member politburo or even the PSC. Such high-level elections, however, did not take place. The selection of elites at this congress continued to be done the old fashioned way—through the “black box” of manipulation, deal-cutting, and trade-offs that occur behind the scenes among a handful of politicians (e.g., outgoing PSC members and retired heavyweight figures—most noticeably the 86-year old Jiang).

What is even more troubling is the fact that four out of the seven PSC members are princelings—leaders who come from families of either veteran revolutionaries or high-ranking officials. It has been widely noted that large numbers of prominent party leaders and families have used their political power to convert state assets into their own private wealth. The unprecedentedly strong presence of princelings in the new PSC is likely to reinforce public resentment of how power and wealth continue to converge in China.

Chinese politics thus seem to be entering a new era characterized by the concentration of princeling power at the top. This gives rise to important questions regarding the nature and implications of the new leadership. What caused the dramatic defeat of the Hu camp in this political succession? Does the six-to-one split of the PSC mean a shift from factional power-sharing to a new “winner takes all” mode of Chinese elite politics? Will the factional imbalance at the top seriously undermine leadership unity and elite cohesion, thus potentially threatening the sociopolitical stability of the country at large? What are the main characteristics of this new princeling elite? What should we expect in terms of economic policies, political reforms, and foreign relations under the Xi Jinping administration? And can the identities of newly promoted leaders help us understand where China is headed?

Because of the key role China plays in the global economy and in regional security, the international community needs to grasp these new tensions and dynamics in the Chinese leadership now emerging at a time when the Middle Kingdom is facing many daunting challenges. How the princelings govern China, especially how state-society relations unfold, will undoubtedly have profound ramifications far beyond China’s borders.

One Party, Two Coalitions

Though China is a one-party state in which the CPC monopolizes power, the party leadership is not a monolithic group. CPC leaders do not all share the same ideology, political association, socioeconomic background, or policy preferences. Two main political factions or coalitions within the CPC leadership have been competing for power, influence, and control over policy initiatives since the late 1990s.

This bifurcation has created within China’s one-party polity something approximating a mechanism of checks and balances in the decision-making process. This mechanism is, of course, not the kind of institutionalized system of checks and balances that operates between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches in a democratic system. But this new structure—sometimes referred to in China as “one party, two coalitions”—does represent a major departure from the “all-powerful strongman” model that was characteristic of politics in the Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping eras.

One of the two intra-party groups in China is the “elitist coalition,” which emerged in the Jiang Zemin era and used to be headed by Jiang and is currently led by Xi Jinping. The other is the “populist coalition,” which was led by President Hu Jintao prior to the 18th Party Congress and is now headed by his protégé Li Keqiang.

These two coalitions represent different socioeconomic and geographical constituencies. Most of the top leaders in the elitist coalition, for instance, are princelings. Many of these princelings began their careers in the economically well-developed coastal cities. The elitist coalition usually represents the interests of China’s entrepreneurs and emerging middle class. Most leading figures in the populist coalition, by contrast, come from less-privileged families. They also tend to have accumulated much of their leadership experience in the less-developed inland provinces. Many advanced in politics by way of the Chinese Communist Youth League and have therefore garnered the label tuanpai, literally meaning “league faction.” These populists often voice the concerns of vulnerable social groups, such as farmers, migrant workers, and the urban poor.

Some clarifications about China’s intra-party factionalism are in order. Factional politics and political coalitions in present-day China, although not really opaque to the public, still lack transparency. With a few noticeable exceptions—such as former party chief of Chongqing Bo Xilai and party chief of Guangdong Wang Yang, both of whom conducted distinct self-promotion campaigns a couple of years prior to the 18th Party Congress—a majority of political leaders in China usually take a low-profile approach, lobbying for promotion in a non-public manner. Unlike the decades of Liberal Democratic Party hegemony in Japan (1955–94), for instance, factional politics within the CPC have not yet been legitimated by the party constitution. A few leaders may have dual identities as both princeling and tuanpai, although one can usually identify their factional affiliations by the channel through which they are promoted and who their patrons are.

Leaders of these two competing factions differ in expertise, credentials, and experience. Yet they understand the need to compromise in order to coexist—especially in times of crisis. By and large, these two competing camps have maintained a roughly equal factional balance of power over the past decade. The previous nine-member PSC, for example, was characterized by a five-to-four split, with five seats held by the elitist coalition and four by the populist coalition.

The Hu Camp’s Waterloo

This factional balance of power now appears to be broken. There were three eligible candidates who served on the previous politburo and met the age requirement but failed to be elevated to the PSC at the 18th Party Congress—all were tuanpai leaders. These include the only woman candidate, State Councilor Liu Yandong, and two rising stars, the aforementioned Wang Yang, and former head of the CPC Organization Department Li Yuanchao. All three, especially Wang and Li, are regarded as staunch advocates of political reform.

The Chinese public will likely understand why Wang was not elevated: many conservative leaders saw him as a threat. Wang’s main political rival was Bo Xilai, and the two tended to balance each other in terms of power, influence, and policy agenda. Now that Bo is out of the political game, the conservatives do not want Wang to remain in it. That Li Yuanchao was not elevated, however, was surprising. In charge of personnel promotion within the CPC over the past five years, Li carried arguably the strongest weight in selecting delegates to the 18th Party Congress. An instrumental voice for rule of law, governmental accountability, and intra-party democracy, Li has many supporters, especially among liberal intellectuals. He has also played a crucial role in recruiting foreign-educated returnees and promoting college graduates who work as village cadres.

Furthermore, at the congress Hu Jintao ceded his military position instead of following the practice of his predecessor Jiang Zemin, who retained the chairmanship of the powerful Central Military Commission (CMC) for two years after resigning from the formal party leadership. Now the number of princelings in this supreme military leadership body is unprecedentedly high. Four of the eleven members of the CMC are princelings, doubling the representation of princelings since the formation of the previous CMC five years ago.

This outcome is particularly startling when one considers the fact that Hu Jintao and his ally Wen Jiabao decisively expelled Bo, a notoriously ambitious princeling, from the party in 2012. This occurred in the wake of the dramatic incident in which former Chongqing police chief Wang Lijun defected to the United States Consulate in Chengdu, and the subsequent revelation of the murder of British businessman Neil Heywood, carried out by Bo Xilai’s wife. By levying a long list of criminal charges against Bo (presently awaiting trial)—including obstruction of justice, abuse of power, violation of party rules, bribery, and other crimes—Hu and Wen seemed to have won a landmark political battle.

The Bo Xilai scandal was a huge blow for the princeling faction. How is it possible that leadership infighting has taken yet another dramatic twist since his downfall? What has caused this profound change in the power equation? Though full answers to these politically sensitive issues will perhaps take time to emerge, clues have already surfaced.

The first relates to the now well-known Ferrari crash that occurred in Beijing on March 18, 2012, three days after the Chinese authorities fired Bo Xilai as Chongqing party chief. The crash immediately killed the driver, who was the son of Ling Jihua, the then director of the CPC General Office and Hu Jintao’s chief of staff. It also critically injured two young female passengers, one of whom died mysteriously at the hospital months later. It was believed that Ling not only managed to hide his son’s death from the leadership but also asked the CEO of the China National Petroleum Corporation to pay a large sum of money to the families of the two women in exchange for their silence, and even ordered the Central Guard Bureau, China’s secret service corps that manages the top leaders’ security, to handle—and cover up—the incident.

There have been two main rumors explaining how Ling Jihua sought to cover up the crash. One is that Ling helped fabricate information about the incident, which spread by social media, stating that the dead driver was a son of then PSC member Jia Qinglin. Upon hearing such rumors, an outraged Jia brought his grievance to the top leadership, including former party chief Jiang Zemin. The other rumor is that Ling attempted to make a deal with a prominent princeling, then PSC member and police tsar Zhou Yongkang, who was involved in the Bo Xilai scandal. The deal was simple: Zhou would help Ling cover up the car crash incident, and in return Ling would refrain from investigating Zhou’s involvement in the Bo case.

Regardless of which rumor holds the most truth, the Ling scandal was the second earthquake to rock Chinese elite politics last year, second in magnitude only to the Bo crisis. Ling has long served as Hu’s closest confidant and “political fixer.” This episode has severely damaged the authority and credibility that Hu Jintao wields in the leadership. The PSC’s decision in July to remove Ling from his post as director of the powerful General Office and to instead appoint him to a less important post was seen by many as a prelude that the Hu camp would be far less competitive in the power jockeying of the fall congress than had been previously thought.

The second incident was the accusation that Premier Wen Jiabao’s family was corrupt. This charge was widely circulated both by Chinese social media and in the foreign press, notably by the sensational story published by the New York Times in October charging that Wen’s relatives have controlled assets worth $2.7 billion. Whether or not Wen and his immediate family have been involved in illegal business activities is not clear. What is also not clear is whether this accusation against Wen was initiated by his political rivals.

The ideological differences between Wen on one end of the factional spread and politically conservative leaders in the Jiang camp on the other, however, are widely known to the Chinese public. Over the past several years, Wen has consistently emphasized the universal value of democracy, the political bottlenecks that undermine Chinese economic development, and the necessity for fundamental political transformation in the country. In contrast, Wu Bangguo, the second-highest ranking leader in the previous PSC and a heavyweight leader in the Jiang camp, rejected Wen’s call for democratic reform by claiming that the Wen’s appeals (for elections, constitutionalism, and media supervision) would lead the country into an uncharted sea of drastic political change or even chaos, and thus should be resisted at all cost.

The timing of the latest wave of criticism against Wen that circulated in both the Chinese social media and overseas mainstream news outlets has effectively undermined the premier’s reputation and sabotaged his well-known political reform agenda. Wen, potentially the strongest supporter of like-minded political reformers in the fifth generation (such as Wang Yang and Li Yuanchao), was thus forced to fall largely silent during the most crucial period of the leadership succession.

Third, even without these two incidents, the Hu-Wen administration has confronted an increasingly profound sense of public disappointment and criticism as the Hu era wound to a close. Hu has been criticized by the political and economic elites in the country, including the middle class, for his “inaction” (wuwei), a frequently used term in both Chinese blogs and daily conversations in the country. Some critics also portrayed Wen Jiabao as an ineffective premier who is famous for crying in public but not for getting things done. Some prominent Chinese public intellectuals have openly called the two five-year terms of the Hu leadership “the lost decade.”

For many critics, Hu’s rhetoric of a “harmonious society” (a buzzword in the Hu era for the principal policy objectives of reducing social tensions and economic disparity) resonates poorly (and ironically) given that the country’s Gini Coefficient, the standard measurement of the income gap, has worsened. Since 2002 it has risen to 0.48 in 2009 and to 0.61 in 2010, according to two recent studies conducted by the World Bank and China’s Southwestern University of Finance and Economics respectively, far exceeding the 0.44 figure that scholars say indicates the potential for social destabilization. Furthermore, the country’s spending on internal public security has skyrocketed in recent years, for the first time overtaking spending on national defense in 2010 to the tune of $84 billion.

On the foreign policy front, critics have argued that Hu’s “good neighborhood policy” has largely failed because China seems to have generated serious tension or distrust with virtually all of its neighboring countries, including a number of flash points along China’s borders and seas. China confronts an increasingly complicated and challenging international environment yet, despite its growing power and influence on the world stage, has few friends.

Disillusionment over Hu’s leadership is arguably most salient among the vast number of the country’s middle class. Members of this stratum often complain that they (rather than the upper class) shoulder most of the burden incurred by Hu’s harmonious society policies that are targeted at helping vulnerable socio-economic groups. Another thing angering the middle class is the high unemployment rate among college graduates, who often come from middle class families: nearly two million each year fail to find work. The admission rate for civil service exams has fallen remarkably low, reaching just 1.9 percent this year, in sharp contrast to ten years ago when government employees were leaving to “jump into the sea of the private business sector” (xiahai). This change reflects the shrinking of the private sector in recent years.

However, it is too early to hand down a definitive verdict regarding the legacy of the Hu era. For instance, many of the issues that emerged or were not resolved during Hu’s administration may have structural or cyclical origins and thus were beyond his control. The above criticisms also reflect only the views of certain groups such as opinion leaders and the middle class. Hu and Wen may remain popular among the vast number of peasants and migrant workers; and Wen may still have strong support from liberal intellectuals in the country. Many problems might also be attributable to policy deadlock—and political gridlock—caused by the factional jockeying as played out in the collective leadership. It is possible that the situation could have been even worse without Hu and Wen’s efforts to constrain the powerful elitist coalition. Nevertheless, the fact that Hu has been in charge during the past decade has made him the natural target for blame.

More importantly, the argument that factional deadlock was at the root of the Hu-Wen administration’s ineffectiveness has now apparently played into the hands of Jiang’s camp. If a more balanced factional composition at the PSC has often led to policy deadlock, why shouldn’t the 18th Party Congress have a leadership lineup where power is concentrated in the hands of the new top leader Xi Jinping and his team? This is another important factor behind the six-to-one split of the new PSC.

This does not mean, however, that the winner now takes all in Chinese elite politics. Hu’s protégés are still well represented in other important leadership bodies. Although the Jiang camp has dominated the new PSC, the balance between the two camps in the 25-member politburo, the Secretariat (the organization that handles daily administrative affairs), and the CMC have largely remained intact. In fact, many tuanpai leaders have made it into the new 376-member Central Committee. This writer’s research indicates that tuanpai leaders now occupy ninety-six seats in the new Central Committee constituting 25.5 percent of this very crucial decision-making body, a steep uptick when compared with the tuanpai’s eighty-six seats in the previous 371-member Central Committee (23.2 percent).

Prominent tuanpai leaders such as the aforementioned Li Yuanchao and Wang Yang will still be eligible in terms of age for the next PSC in five years. If the “one party, two coalitions” dynamics is a new experiment in Chinese elite politics, the CPC can also experiment with a new mechanism of “factional rotation” (paixi lunhuan). This may explain why the Hu camp quietly acquiesced to its political Waterloo in the latest leadership succession.

Xi’s Mandate

Xi Jinping has had an auspicious beginning as China’s new leader. He enjoys a majority in the PSC and is the top leader in the wake of a complete succession in both the party and military leadership. Xi thus has obtained the power and authority to initiate his new policy agenda. His predecessor’s unpopularity among opinion leaders and the middle class has also enhanced Xi’s public support—giving a sense that he has a new mandate. In the wake of the recent Bo Xilai and Ling Jihua scandals, all party elite regardless of factional affiliation will unite, at least for the time being, under Xi’s leadership in order to maintain CPC rule.

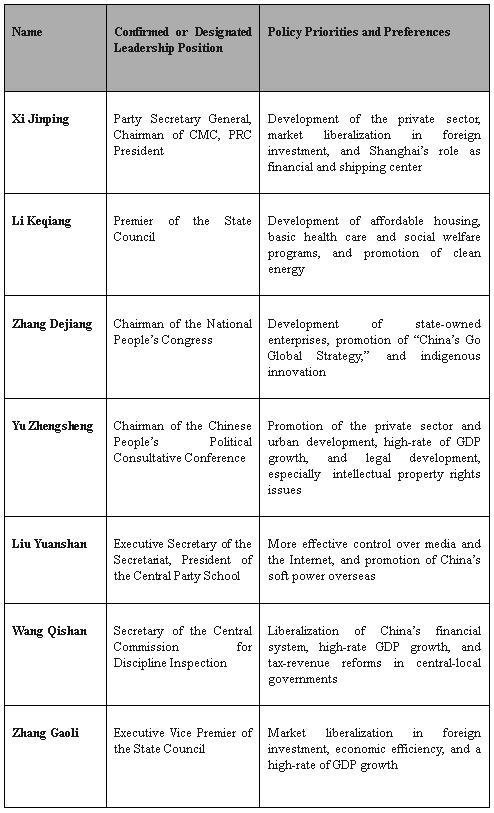

Most importantly, the new leadership seems to be very capable on the economic front and it has strong policy preferences for accelerating market reforms (see chart). Four princeling leaders on the PSC—Xi Jinping, Zhang Dejiang, Yu Zhengsheng, and Wang Qishan—all have decades of experience and high levels of competence in economic and financial affairs. Some Chinese analysts argue that due to their princeling background, these leaders have more political capital and resources than did their predecessors Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao (who came from humble family backgrounds) in terms of running the Chinese economy and coordinating various governmental agencies.

Table 1: Policy Priorities and Preferences of China’s Top Seven Leaders (New PSC Members)

Xi has long been known for his market-friendly approach to economic development for domestic and foreign businesses alike. Xi’s leadership experience in running Fujian, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, three economically advanced regions in the country, has prepared him well for pursuing policies to promote the development of the private sector, foreign investment and trade, and the liberalization of China’s financial system—all of which have experienced serious setbacks in recent years under the previous administration. Another good example of effective leadership is Wang Qishan, the newly appointed anti-corruption tsar. Over the past few years Wang has served as a principal convener for China in the Sino-U.S. Strategic and Economic Dialogue. Wang, whose nickname is “the chief of the fire brigade,” is arguably the most competent policy maker in economic and financial affairs in the Chinese leadership. The Chinese public regards Wang as a leader who is capable and trustworthy during times of emergency or crisis, whether it be China’s response to the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, or China’s ongoing rampant official corruption. Based on his previous leadership experiences and policy initiatives, Wang will most likely promote the development of foreign investment and trade, the liberalization of China’s financial system, and tax-revenue reforms, which are all crucial for the maintenance of smooth central-local economic relations.

In spite of (or because of) their weaknesses and liabilities in terms of fundamental political reforms, the new leaders will likely opt for bolder and more aggressive economic reforms to lift public confidence. The upcoming economic reforms will probably prioritize three sets of policies. First, the new leaders will work hard to please the middle class. Such policies would include tax cuts, more loans to private small and medium enterprises (SMEs), and more preferential policies to the services sector. A richer and larger middle class in China would also help to stimulate domestic consumption, the next driver for China’s economic growth. Second, the new leaders will promote financial liberalization by inviting more foreign competition to the Chinese banking sector. Finally, they will accelerate urbanization, especially in second- and third-tier cities, by reforming policies involving both rural land reform and the urban household registration system (hukou).

Xi Jinping’s first domestic trip after becoming the party general secretary was to Shenzhen, the point of origin for Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening” policy in the late 1970s. China’s stock market, after two years of sluggishness, rebounded very strongly after Xi’s symbolic trip. The central question, however, is whether or not Xi and the princeling-dominated PSC can achieve sustainable economic development without pursuing systemic political reform. Can China really adopt an innovation-driven economy while the country’s political system remains as it is?

Daunting Challenges

The ascent of the princelings has occurred at a time when public criticism of rampant official corruption is unprecedentedly high. Some Chinese public intellectuals use the term “statist crony-capitalism” (quangui zibenzhuyi) to refer to the growing phenomenon in which senior leaders and their families control some state-monopolized industries or major state-owned enterprises (SOEs) for their own profit. This cronyism is especially noticeable in the major business domains such as railways, petroleum, utilities, banking, and telecommunications.

The remarkable growth of some SOEs such as China Mobile, for example, has primarily been attributed to the company’s monopoly on telecommunications in the Chinese domestic market. This has two troubling consequences. First, there is no incentive for these flagship companies to pursue technological innovation. While China’s large SOEs have dramatically increased their profitability and standing among the Global Fortune 500 over the past decade, no single Chinese brand has truly distinguished itself in the global market. Second, the real beneficiaries of China’s economic rise on the world stage are not the Chinese people, but merely a small number of corrupt officials and their families.

The state-of-the-art high-speed train system is often seen as the symbol of China’s economic take-off, but the country’s railway industry has been running a budget deficit. China’s official media recently reported that a bureau-level official in China’s Ministry of Railways held Swiss and American bank accounts with assets of $2.8 billion. What is even more astonishing has been the scandal involving the former minister of railways, Liu Zhijun. Liu’s nickname—“Mr. Four Percent”—derived from his reputation for demanding a personal cut of every business deal in the industry. According to the Singapore media, Liu intended to spend two billion yuan ($320 million) to “purchase” the post of vice premiership, and even a seat in the 2012 politburo, before he was arrested on corruption charges in February 2011. Almost two years after the arrests of the bureau-level official and the minister, the two cases have not yet been tried.

According to an internal report by the CPC Organization Department, of the 8,370 senior executives in China’s 120 flagship state-owned companies, 6,370 (76 percent) have immediate family members who live overseas or hold foreign passports. It is also widely noted that a significant number of children and siblings of senior CPC leaders live, work, and study in Western countries. The Chinese public has often linked this trend to the large-scale outflow of capital in recent years. According to a 2012 report released by Washington-based Global Financial Integrity, cumulative illicit financial flows from China (primarily by corrupt officials) totaled a massive $3.8 trillion from 2000 to 2011.

Since a top priority of the CPC leadership is the maintenance of its own rule, it is no surprise that the police have become more powerful, not only in terms of their input into socioeconomic policies but also in terms of budget allocation. For example, the total amount of money used for “maintaining social stability” in 2009 was 514 billion yuan—almost identical to China’s total national defense budget (532 billion yuan) that year. The Chinese government budget for national defense in 2012 was 670.3 billion yuan, while the budget for the police and other public security expenditures was 701.8 billion yuan (an 11.5 percent increase).

Two factors have contributed to the growing power of the police force. First, the Arab Spring led CPC leaders to fear that they could face an outcome similar to that, for example, of the Hosni Mubarak regime in Egypt. Second, business elites—especially those who work in state-monopolized industries—have often bribed government officials including police officers and formed a “wicked coalition.” This coalition constantly talks about the need for stability in the country but in fact is more concerned about maintaining its own interests.

The oligopoly of SOEs not only jeopardizes the commercial interests of foreign companies but also hurts the country’s own private enterprises, thus detracting from the long-term potential of China’s market economy. A study conducted by Chinese scholars shows that the total profits made by China’s 500 largest private companies in 2009 were less than the total revenues of two SOE companies, China Mobile and Sinopec. Ironically, the private sector’s net return on investment was 8.18 percent, compared to the 3.05 percent return of SOEs in the country in 2009.

All this not only shows that China’s future economic development will increasingly depend on much-needed political reforms, but also reveals the enormous challenge for the new leadership in its pronounced commitment to crack down on official corruption. This commitment is as essential as it is dangerous, because the sociopolitical demands unleashed will be overwhelming. Ultimately, it is a test of Xi Jinping and Wang Qishan’s anti-corruption campaign. Is it driven merely by factional interest in getting rid of political rivals? Will it primarily target “small potatoes”? Will it simply be adopted as a temporary tactic instead of pursuing the institution building necessary to effectively control corruption?

It is interesting to note that within a week after Xi and Wang made their speeches calling for a tougher crackdown on official corruption, journalists in the commercial media and netizens using social media leveled accusations against three senior leaders—one new politburo member and two ministers—of nepotism in elite recruitment, fake academic credentials, womanizing, and corruption. Social media has become so influential that Chinese authorities often shut down domestic micro-blogging services.

China’s various new economic and sociopolitical forces are also becoming increasingly protective of their interests. For example, a manual labor shortage in some coastal cities in recent years has reflected the growing political consciousness of the younger generation of migrant workers to protect their own rights. Migrants, effectively second class citizens in China, are resentful over all manner of discriminative policies. They have moved from one job to the next in order to receive a decent salary. Due at least partly to their repeated demands, China has recently witnessed a dramatic increase in wages.

More broadly, as the American political scientist Minxin Pei has observed, the Chinese citizenry now routinely challenges the party on a wide range of public policy issues, including environmental protection, public healthcare, food safety, social welfare, social justice, rural land reforms, urban development, religious rights, and ethnic tension. Official statistics report that there are on average 500-plus mass protest incidents each day.

The lack of a legal channel for public participation combined with tight police control has created a vicious circle in which the more fiercely the police suppress social protests, the more violent and widespread the protests become. There is a similar vicious circle in the realm of the media: the more that sensational rumors in social media are suppressed by the government, the more influential they become.

Meanwhile, growing popular nationalistic sentiment, particularly xenophobic views against the Japanese government (and perhaps the United States government as well) over the territorial disputes on the East China Sea, also constitutes a major political challenge for the Xi administration. Contemporary Chinese history shows that the practice of trying to distract the public from domestic problems by playing up foreign problems has often ended with regime change. Xenophobic public sentiments can quickly transform into an anti-government uprising. Yet CPC leaders may be cornered into taking a confrontational approach to foreign policy due to the nationalistic appeal from both the Chinese military and left-wing opinion leaders.

All of these sociopolitical challenges are reinforcing the necessity and urgency for profound democratic political reforms. A democratic system, of course, can neither solve social tensions nor the problem of extreme nationalism. Yet, it does provide a much better chance to channel social conflicts through the legal process and provide open debate in search of a more rational foreign policy.

The sense of urgency was bluntly explained on the eve of the 18th Party Congress by Zhang Lifan, a well-known public intellectual in Beijing: “If the next generation of leaders does not pursue political reforms in their first term, there is no point in doing so in their second term.” In his words, “China should witness either reforms in the first five years, or the end of the CPC in ten years.” Interestingly enough, in speeches given after becoming party general secretary, Xi Jinping also talked about the possible collapse of the CPC if the leadership failed to seize the opportunity to reform and revitalize the party.

Some Chinese liberal intellectuals explicitly regarded Xi as mainland China’s Chiang Ching-kuo. Also a princeling (the son of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek), Chiang Ching-kuo surprised many in the mid-1980s with his bold and historical move to lift the ban on opposition parties and media censorship in Taiwan, initiating the island’s transition from authoritarianism to democracy.

The next few years will likely tell whether Xi will be a transformative leader, or merely a transitional leader.

Download » (PDF)

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Rule of the Princelings

February 10, 2013