Financial safety nets protect households from cascading into poverty when income unexpectedly drops. Government transfer programs—food stamps, Supplemental Security Income, and Medicaid—kick in when household income drops below a designated threshold. But millions of American families rely on another, very different, safety net to help them through tough times: their own retirement savings.

Retirement Accounts as Personal Safety Nets

Retirement accounts are of course designed to encourage the accumulation of assets for retirement. In general, savers cannot access their retirement wealth before age 59 ½. But there are a few exceptions. Workers with retirement accounts who leave their jobs can either rollover their wealth into another account or take it as a “lump sum” distribution, paying income tax and a 10 percent penalty. And most plans offer employees options for accessing their wealth while still employed, either as a loan from their own account or as a “hardship withdrawal” that can be taken under particular circumstances—such as to make medical payments or to avoid foreclosure. Owners of IRAs can tap their retirement wealth without penalty under a similar set of circumstances.

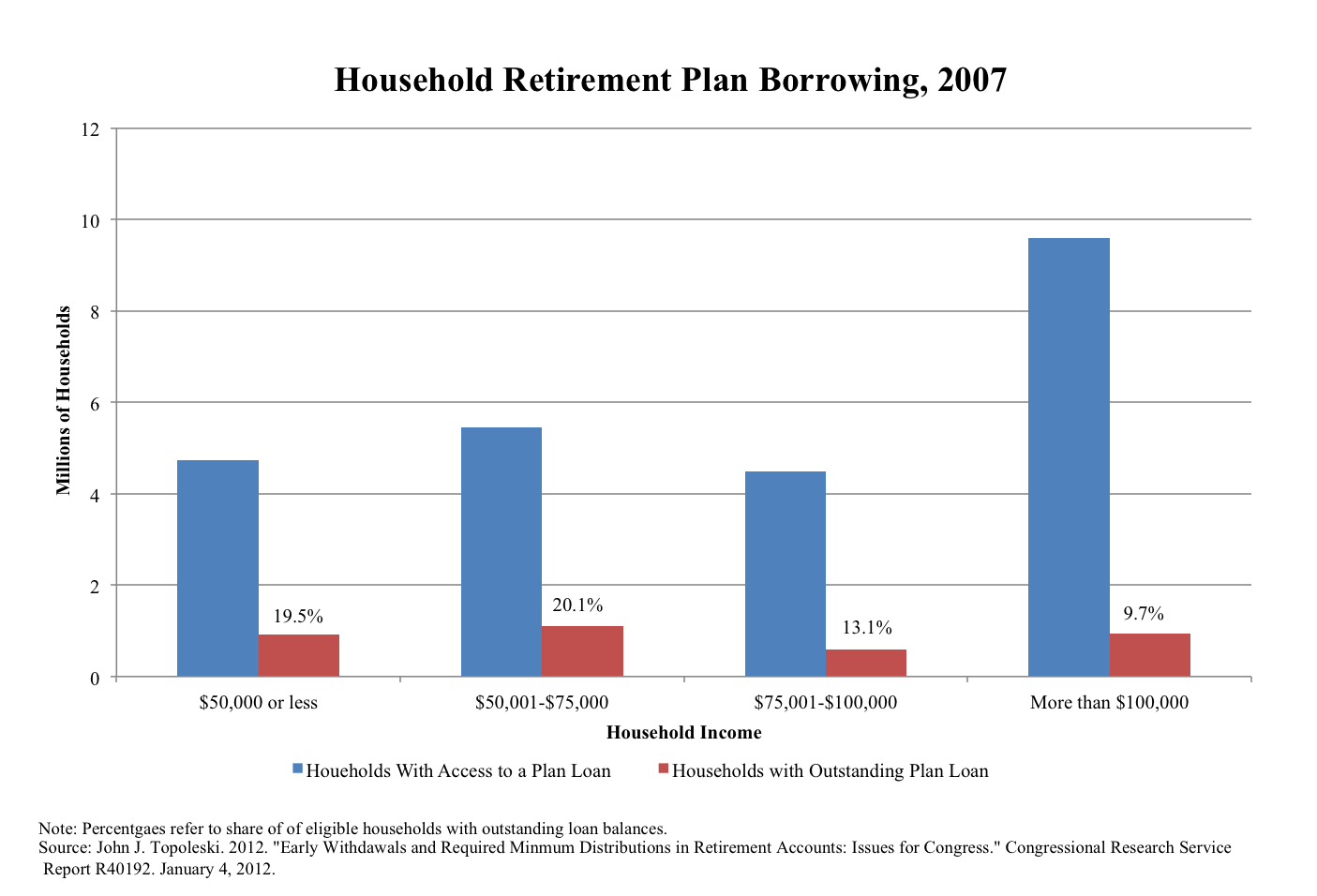

There is huge potential for access to retirement assets to supplement the U.S. safety net. At the start of 2014, Americans held $6.0 trillion in employer-based retirement accounts and an additional $6.6 trillion in IRAs. In 2007, nearly 28 million households had access to hardship withdrawals and another 24 million were in a position to borrow against their retirement assets. But this widespread access did not translate into high take-up: in 2006 just 3 percent of 401(k) participants took a hardship withdrawal and only 8 percent initiated a loan.

Early Access to Retirement Accounts is A Double-Edged Sword

Retirement experts see these early-access provisions as a double-edged sword. On one hand, the ability to access funds during tough times makes retirement saving more attractive. Workers might not give so readily to accounts if they are strictly prohibited from accessing these funds before retirement. On the other hand, unpaid loans and hardship withdrawals represent “leakage” from retirement assets, potentially threatening well-being in later years.

Research confirms that leakage due to hardship withdrawals and unpaid loans is small, amounting to just $10 billion in 2006. (Leakage due to lump-sum payouts when workers leave their jobs is another story, causing $74 billion in leakage.) Studies have also shown that workers use these mechanisms when they truly need them—often after a divorce, a steep drop in income, or to purchase a new home. And these fallbacks are more frequently used by those with low incomes: nearly 20 percent of low-income households with access to a loan had taken one, compared to less than 10 percent of high-income households.

Needed: More Retirement Accounts for Low-Income Households

The big problem is that the lowest-income households—those who most need access to inexpensive emergency credit—often don’t have a retirement account. As policymakers search for strategies to lighten the devastating effects of payday loans and high credit card balances on poor families, one promising path forward lies in enabling all Americans to save for retirement, and in the process contribute to their own personal safety net.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Retirement Accounts as Personal Safety Nets

August 25, 2014