With the 2035 exhaustion of the Social Security trust fund looming, policymakers are—or ought to be—searching for solutions to bolster the finances of one of America’s most beloved programs.

The primary reason for Social Security program’s challenging finances is the demographic transition that the U.S. experienced over the last 70 years. The fertility rate among American women has steadily declined since the end of the Baby Boom in the 1960s due to cultural shifts in gender roles, women going to college and investing in their careers, and increased access to family planning. At the same time, improvements in medicine have significantly lengthened the lifespans of older Americans. These coexisting trends work together to produce an aging population in the U.S.

This shift has caused an increase in the old-age dependency ratio—the number of adults aged 65 and up per 100 people ages 18-64. In 1970, the ratio was 18; by 2020, it had risen to 28. Census projections indicate that this trend will continue, with the old-age dependency ratio expected to reach 53 by 2100; in other words, there will be one adult aged 65 and up for about every two working-age adults (see Fig.1). The ratio is important for Social Security financing because the system is largely “pay as you go,” with the taxes taken out of workers’ paychecks funding benefits for current retirees. By 2035, only about 75% of Social Security benefits will be fundable under current law. The most direct fixes—raising taxes and cutting benefits—are unpopular among voters.

Population pyramid diagrams can help visualize the shifting demography of the U.S. population. These diagrams show the breakdown of a population by age group and gender and can indicate directions of certain population trends, such as fertility rates. The diagram gets its name from the traditional pyramidal shape of many populations, with larger populations at younger ages and very few older adults. Today, many countries in Africa and some in Central America continue to have pyramid-shaped age structures because of higher death rates and high fertility rates. On the other hand, many countries in Asia and Europe have transitioned similarly to the U.S. Comparing the U.S. population pyramids for 1920, 1970, and 2020 demonstrates how changes in fertility and death rates have caused a shift to a demographic “pillar,” leaving a large population of retirees to be supported by a relatively smaller population of workers. Further, the projected pyramid for 2050, created using U.S. Census Bureau’s estimates taking into account births, deaths, and migration trends, shows an even more top-heavy demography, with many more people in the 85+ category than ever before.

Immigrants to the U.S. can help by adding to the working-age population and supporting the economy. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), in 2023 the foreign-born, or first-generation, population made up 18.6% of the labor force, an increase from only 5.3% in 1970. The BLS also reported that foreign-born men were significantly more likely to participate in the labor force than U.S.-born men, with a 77.5% participation rate compared to 66.1%, respectively. Foreign-born women, on the other hand, were slightly less likely to participate than their native-born counterparts at 56.1% compared to 57.6%, respectively. Economic research also makes it clear that immigration expands the number of jobs in the workforce, finding that U.S. states with higher immigration inflows experienced relatively larger gains in employment compared to those with lower rates of immigration. Not only do immigrants improve the old-age dependency ratio by supplementing the working age population, but they also boost overall fertility rates. In 2023, the total fertility rate (TFR), measured as the number of births per woman, was 1.62. This rate was 2% lower than the TFR in 2022 and far below the replacement rate of 2.1. Though fertility is declining for both foreign- and U.S.-born women, foreign-born women had a significantly higher birth rate than native-born women ages 15-44 in 2017, according to Census and NCHS data: 77.4 births per 1,000 women and 56.2 births per 1,000 women, respectively. The same data shows that while immigrants made up 14% of the U.S. population in 2017, they accounted for 23% of all births.

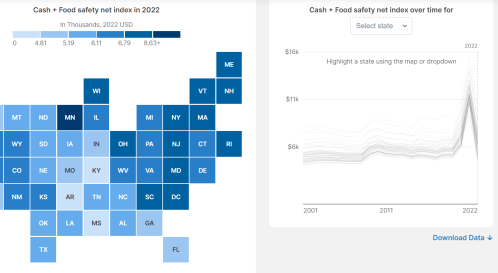

The graphs below show how first-generation immigrants and their children support the aging U.S. population today by widening the base of the population “pyramid.”1 Excluding the two outermost categories—first-generation immigrants and second-generation U.S.-born children of immigrants—results in an even higher old-age dependency ratio for the U.S. population. By this calculation, the ratio is 30 rather than 28 for the year 2020, illustrating how immigrants and their children are critical to maintaining a strong workforce. Changing dramatically in fifty years, the bulk of the foreign-born population today is concentrated at working ages, and the second generation will be a large fraction of the workforce in the coming decades.

The Social Security actuaries consider immigration to be an important determinant in the health of the Social Security system. The 2024 Trustees Report shows a long run deficit in the program that is about 25% smaller in the high-immigration scenario compared to a low-immigration scenario, or an average annual total net immigration of 1,683,000 people compared with 829,000 people. The contributions of immigrants to payroll tax revenue, including those from undocumented immigrants working in formal sector jobs, are a key reason that the overall fiscal effects of immigration at the federal level are so positive.

To be sure, a one-time surge in immigration is not a permanent fix to Social Security’s financing problem. Immigrants who work in the U.S. and legally pay into the Social Security system will be later recipients of benefits as they age. But immigration today helps extend the time Congress has to make necessary changes to tax or benefit rates, and a policy allowing for continued inflows of new migrants improves the sustainability of the program.

The incoming Trump administration is poised to limit the number of immigrants in the United States through curtailing legal migration, reducing undocumented migration, and ramping up deportation. As a result, Americans can expect slower growth in the labor force in the coming years. However, there are ways to mitigate the harm to the Social Security system, particularly if Congress is willing to take action and address the labor needs of the economy. The negative economic impacts of tighter border control could be partially offset by targeted expansions in legal pathways for the millions of people around the world who are interested in contributing to the American economy.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports, published online. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- To determine the number of people who were second-generation in 1980 and 1990, we imputed the ratios of the second-generation population to a combined second-generation and third-generation population for each year using IPUMS ACS data for 1970 and IPUMS CPS data for 1995.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Immigration and the future of Social Security

December 17, 2024