There is something that is beautiful about Appalachian spirit, and grit and people that live here and that have called this place home for generations.

Kim Effler

Over the past several years, a set of partners in Old Fort, North Carolina, has been developing a network of elite mountain bike and hiking trails that was starting to put the town on the map. In September 2024, Hurricane Helene left the place in ruins, damaging homes, trails, and more than a dozen businesses that had opened as the outdoor recreation economy took hold. In this episode, the first in season 3 of Reimagine Rural, Tony Pipa visits this small western North Carolina town to learn how it plans to keep its vision for a just and sustainable future intact as it continues to rebuild after the storm.

Featuring:

- Kim Effler, President & CEO, McDowell Chamber of Commerce

- Jason McDougald, Executive Director, Camp Grier

- Chad Schoenauer, Owner and Operator, Old Fort Bike Shop

- Pam Snypes, Mayor of Old Fort, North Carolina

- Stephanie Swepson-Twitty, President and CEO, Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation, CDC

Want to learn more? Read Tony’s interview with Matt Calabria, director of the Governor’s Recovery Office for Western North Carolina, on how state leadership is coordinating recovery after the most devastating storm in state history.

Transcript

[sound of water rushing; music]

PIPA: On September 27, 2024, Hurricane Helene brought catastrophic rainfall to the southern Appalachian mountains. The storm led to at least 250 deaths across six states and damaged tens of thousands of homes and businesses. In North Carolina, 108 people lost their lives. In Old Fort, a town of around 800 people about 25 miles east of Asheville and surrounded by the Pisgah National Forest, Helene’s force raised railroad tracks off the ground, upended bridges, washed out roads, destroyed almost 50 homes, and made an additional 36 unlivable.

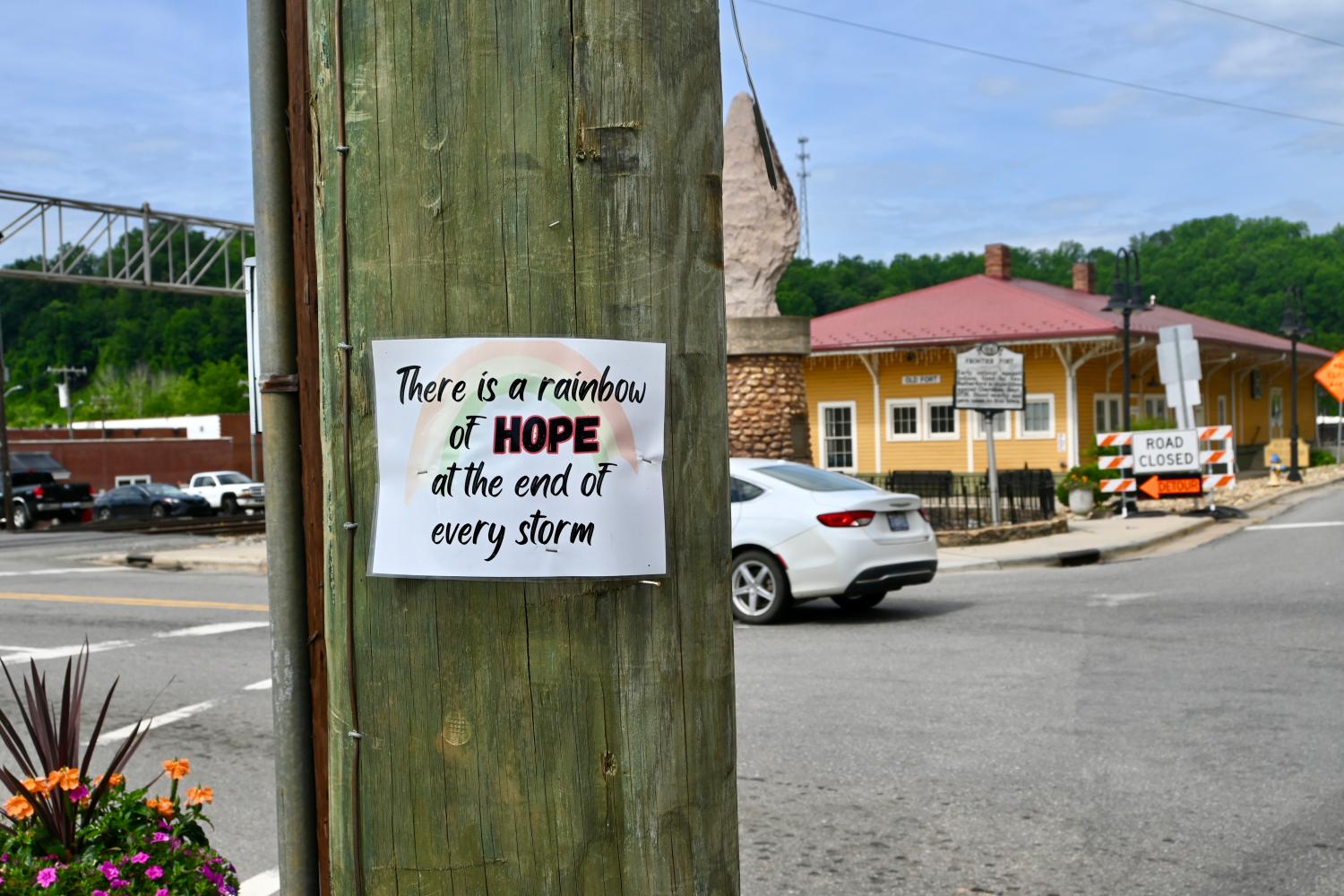

The audio you just heard was of a torrent of floodwater engulfing a country road and splintering an electric pole during the height of the storm. When I visited 8 months later, signs of the damage to Old Fort were still pretty evident.

MCDOUGALD: And this really looks nothing like what it used to. The creek, the stream corridor is probably 50 to 75% wider than it was pre-Helene, you know? That’s the bridge. During the storm, it pushed so much debris, trees, deadfall, houses, all kinds of stuff against the bridge and it basically the water just picked it up and flipped it over. So the bridge is still intact, it’s just upside down and a hundred feet down the stream where it should be.

[music]

So yeah, it’s, it’s crazy how much force that water took to, to overturn a concrete and steel structure of that size.

PIPA: A few days before the hurricane, a trail crew had just finished work on the twentieth mile of a new network rails that was in the works for years. That flipped bridge helped people get to those trails. It was all part of a growing outdoor recreation economy helping to revitalize downtown Old Fort, a former manufacturing town, and turn it into a real destination.

In this episode, we’ll visit Old Fort and hear how residents are rebuilding their lives, and this new economy, eight months after Hurricane Helene tore through the region.

[music]

I’m Tony Pipa, a senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution. And welcome to season three of Reimagine Rural, the podcast where I talk to local people, capture their stories of the changes unfolding in their hometowns, and explore the implications and intersections with public policy.

Pisgah National Forest is one of the country’s most visited national forests, and one of its oldest.

[music]

It has some of the highest peaks in the eastern United States and offers travelers panoramic views of the Blue Ridge Mountains, patches of ancient, old-growth forest, with trails for mountain biking, hiking, and horse-back riding. The forest surrounds Camp Grier, a summer youth camp that started in 1952 as an outdoor ministry of the Presbyterian Church.

[3:25]

MCDOUGALD: We sit really strategically between the town and about 70,000 acres of public land. So we’re really completely surrounded by conserved land. And what makes Camp really unique is that while we have this access to public lands, we’re just minutes from Interstate 40, so that connects us to about 30 million people within a half day’s drive.

PIPA: Jason McDougald is the executive director of Camp Grier.

MCDOUGALD: Yeah, so my grandparents lived in western North Carolina. I grew up coming here as a kid. And my dad owned an outdoor store, and so I grew up in the outdoor world, selling backpacks and water bottles. And one of the benefits of working there was there was a lot of mentors in the outdoor space. So I got introduced to rock climbing and paddling and fly fishing. And we—my wife and I—wanted to live in the mountains and this just felt like a good spot.

PIPA: In 2014, downtown Old Fort had lots of boarded up store fronts. But Jason began thinking about the role Camp Grier could play in shaping an economy around adventure tourism in town.

[4:34]

MCDOUGALD: Kind of what started it all was looking at the map, just looking at this trail called Heartbreak Ridge. It was a legacy trail that had existed in Old Fort for a long time. And just had this idea of if we could really take this trail all the way to town, it would be the longest descent on the East Coast. So over 4,000 feet of downhill riding in about 13 miles.

PIPA: Jason worked with an expert at Appalachian State University and initially drew up plans for six to eight miles of new trails. But as they talked to the U.S. Forest Service and looked at all the possibilities, they eventually got 42 total miles of new trail approved. The trails became the centerpiece of the local economy and the catalyst for new civic collaboration. At a town meeting, Jason met a representative from People on the Move, a Black-led community group in Old Fort, and realized they had common goals.

MCDOUGALD: We wanted to see the town be more vibrant, more economically robust. And, you know, I was just able to convince them that trails were a good way to do that. We felt like this could be a way to really change the town without having to get permission from anybody but the Forest. You know, it was like, well, if we can build trails on public land that is gonna have the effect that we’re looking for. It’s gonna bring in businesses.

[music]

PIPA: People on the Move is a community engagement initiative started by West Marion Community Inc., a local organization committed to getting the local Black community more involved in the civic leadership of Old Fort. African Americans, while a small percentage of the population, had a vibrant history in Old Fort. And as Jason built a relationship with People on the Move, they embraced his vision and included some funding for planning, permitting, and design into a grant proposal they had developed to support Black entrepreneurs.

Not only did that funding cover the critical early stages—all the work that has to happen long before anyone moves a single piece of dirt—but it’s also how he met Stephanie Swepson-Twitty.

[6:41]

SWEPSON-TWITTY: I am a native of Old Fort. I was born and nurtured here. I had a wonderful childhood. We lived right off the edge of the Pisgah Forest and were able to enjoy the amazing beauty of the forest and the play in the mountains. So yeah, that was, that was my childhood and my young adulthood.

PIPA: Stephanie joined Eagle Market Streets Development Corporation as an AmeriCorps fellow in her early 50s. She was deliberately searching for work that would allow her to more directly address the country’s legacy of racial discrimination in banking and finance—her first career. Two years later she became Eagle Street’s CEO.

[7:27]

SWEPSON-TWITTY: Jason and I, because of our relationship and understanding of the not-for-profit world, absolutely locked arms, if you will, and commitment to doing the work in understanding how the economics of this was very intertwined, that if we could develop trails that would draw an audience or visitation that they would need an amenity or amenities that would keep them. And that Eagle had in their development of real estate and small business the capacity to bring that piece of it.

PIPA: At first, some residents were skeptical about this shift from a traditional manufacturing and timber economy to one focused on outdoor recreation.

SWEPSON-TWITTY: I think we still have old-school thinking that for the South that textile manufacturing is still gonna come back and be the champion for the South. That battle wages on even as we sit today and think about these things.

I just would love for the audience to know that when you’re doing these things, even when intentions are well placed, that that often people don’t come with arms wide open embracing things just because the intentions are good.

PIPA: Indeed, many of the people I talked to in Old Fort pointed out valid concerns by residents about the influx of outsiders encroaching upon the natural beauty and quality of life that made Old Fort so special to them. But the business opportunity was undeniable.

[9:20]

SCHOENAUER: They started up a trail project where they were taking the existing 35 miles of trails here in Old Fort and adding 42 more. And that project is ongoing and has produced some incredible riding around here. Once I got word that that was moving forward and it was a definite thing, I came down and started scoping spots.

PIPA: Chad Schoenauer opened Old Fort Bike Shop in August 2021.

SCHOENAUER: This also happens to be the first real area where you’re entering legit mountain biking terrain from the east. This is kind of uncharted territory and people come from Charlotte and Raleigh and all points east and stop in Old Fort to check it all out.

[10:11]

MCDOUGALD: That first six miles and the parking lot was just really proof of concept for the community. It’s like, look, like, we have this asset, and we should be proud of it, and people will travel across the country to come here and experience it.

But I think you’re never gonna get everybody on the same page about what direction to go. But I think in general, most folks wanted to see Old Fort thrive, you know, they wanted their hardware store, they wanted a place to get dinner. In general, the community was really supportive.

And so that adage of, you know, private money following public was really true. We joke that it’s really a business per mile is what we saw. So, like, we’ve built 20 miles of trails and we’re at 20 businesses that, you know, we can point to and say, these weren’t here three years ago.

[music]

[11:02]

EFFLER: It was Tuesday before Helene hit on Saturday, we received a phone call at the Chamber of Commerce that representation was needed at the EOC, the Emergency Operation Center in the county. I was in West Virginia at the time visiting with my family. I left West Virginia on Wednesday, arrived home, packed a bag, and on Thursday headed to the EOC.

I remember the night, the calm before the storm. That phrase means something so differently now than it ever has in my life.

PIPA: Kim Effler is the director of the McDowell County Chamber of Commerce.

EFFLER: And then Helene came and all hell broke loose.

[sound of thunder, lightning]

The 911 call board that was on the wall was empty to then immediately full. Radios were going off on the officer’s belts. There was lots of confusion. Communication was down and we all sort of just settled into finding our place of what do we do to help.

I was prepared and everything that I prepared went away. And I jumped into the human services division of Emergency Operations and immediately our first task was how do we get water into the county and keep people alive?

PIPA: Jason was drinking a cup of coffee that morning in the living room of the director’s house at Camp Grier when a tree fell through the roof above him, sending rain pouring into the house with branches and debris.

[12:46]

MCDOUGALD: And the house was essentially an island at that point. And yeah, just rode it out in my truck for a couple hours and ‘til it started to slack off. The water that was coming through Old Fort was just beyond anything that I’ve ever seen.

Water, sewer, fiber—all that was gone. Landslides, you know, across roads, you couldn’t get anywhere. You know, railroad tracks. It just looked like a roller coaster, just suspended in air.

Walked into town that afternoon and there was probably a foot or two of mud, you know, in the town center. Smelled like natural gas just from all the gas leaks. People wandering around in their house coats and no shoes ‘cause they just got out of their house that morning and watched it float away.

PIPA: Because of a landslide, it took two days before Chad Schoenauer was able to get to his bike shop.

[13:39]

SCHOENAUER: I came off of the interstate and immediately saw what looked like a war zone. And I started crying. I couldn’t contain it. And I saw everybody kind of picking through and walking around in just mud and gross filth. And everything was rearranged, if you can imagine that.

And I made it to the parking lot here and I saw a group of probably 15 people already inside my shop. I had three-and-a-half feet of water come into the shop. I had over a foot of mud here in the shop. And, yeah, totaled is how I would describe it.

[music]

My landlord had already organized getting help and my heart flipped. I became full of gratitude, and I walked in here with a smile and nothing but thanks, and I was high fiving people, and we all got to work.

PIPA: Among the destruction, Camp Grier was a surprising outlier for how little damage it sustained. The creeks washed out and roads were damaged. But the dam at the lake held strong.

[15:03]

MCDOUGALD: I was really surprised because main camp was fine. I couldn’t believe it. So we started really just cooking food and taking it into town. And then somebody gave us a Starlink that first week, and then we were able to communicate a lot easier.

So got in touch with my parents and a couple of other donors, and they were able to source, like, a big generator off the coast of South Carolina. And they brought that up and we hooked it up and that powered all the main camp. And we ran off that generator for about 60 days and just served as a relief hub.

[15:43]

EFFLER: I was in the EOC for seven days. It was the most intense seven days of my entire life. And I really understand now what fight mode, what fight status is when you’re dealing with trauma. I think that the average person is not meant to go through what we as normal people went through in headquarters.

And I think that the trauma is still bubbling up and it’s still coming out, and there are trigger points. A helicopter is a trigger point. The rain that we’ve had today is a trigger point. One day last week, our cell phones went down for about a half a day, and there was panic, like, oh my goodness, we can’t talk to our friends and family and know that people are okay.

So, we believe that there were about a hundred businesses that were affected with either water damage, structural challenges, and the bulk of them were in Old Fort. There’s a section on the Catawba River in Marion where about 17 businesses became flooded.

So here we are eight months later and it’s still very, very real. It’s both heartwarming and heartbreaking all at the same time.

PIPA: Right away, the Army Corps of Engineers was removing debris in the region, including in Old Fort. Within eight hours, they helped Stephanie Swepson-Twitty clean a layer of silt from the first floor of Eagle Market Street’s building.

[music]

It served as a distribution point for emergency relief.

The experience of the locals belies much of the national media coverage politicizing the federal government’s response. Old Fort Mayor Pam Snypes, who came into office just four weeks before Helene hit, said FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, arrived quickly.

[17:40]

SNYPES: They were supportive. We had a lot of FEMA personnel coming here to help and explaining things to us, working with us on, you know, process. FEMA and the state, once they saw the condition of Old Fort, they stepped up for us. I know they get a bad rap a lot, but they have been beneficial in our town.

As far as the paperwork and FEMA and our projects that we’re dealing with, here again, can’t complain too much. I will say that the funding process has been a little bit slow, but we are seeing some reimbursements coming in. Still got a long ways to go.

PIPA: Before coming to Old Fort, Mayor Snypes served as administrator and financial officer of another town, and that experience has been good preparation for dealing with the bureaucratic idiosyncrasies among the different levels of government. Others in Old Fort found aspects of FEMA’s guidelines and processes to be rigid and outdated.

[18:48]

MCDOUGALD: The federal response, you always want it to be faster, but it did come. But what we saw was really inconsistent, like, the rules around how that money could be spent and for whom we’re really limiting. Like, a good example was there’s a statute in FEMA where they don’t pay for second homes, right? Our maintenance director lives at Camp, and he owns a house in Old Fort that he rents to his son. And so that didn’t qualify for FEMA relief.

I think if there was a way where that decision-making could have been somebody with the authority to see like, okay, I understand what this rule is here for, but in this case that doesn’t make sense. This family, this is not their second home. This is affordable housing in a rural community that needs affordable housing, you know, and we need to figure out a way to support it.

And then FEMA would only cover up to $48,000 if the home was completely destroyed. Well, nobody here has flood insurance. So, there’s those limits. So it’s, there was just a lot of gaps and a lot of inflexibility, and it just left a lot of need that was still there to fill.

PIPA: Jason kept Camp Grier running as a relief hub for the community for months, then raised funds to address some of those gaps.

[20:10]

MCDOUGALD: It was 18-hour days for 60 days. And then we have two race production teams that are under our non-profit umbrella. They came and basically said, we’re gonna put on an event at Camp in December, what do you think? And I said, let’s do it if it can raise some money. We had 450 participants sign up in, like, 48 hours to come and do it, and they were all agreeing to raise 1,500 bucks in recovery.

By the end of the year we’d raised almost a million bucks to help rebuild homes and purchase cars. And I think today we’re up to like 1.7 million that we’ve raised. We’ve pushed out about 1.4 now to families. So it’s going to things like paying contractors and supplies and just filling those gaps. We’ve paid off people’s mortgages so that they can go out and get another loan on a new home.

So it’s classic rural. You got a couple of organizations and a few folks that are just putting on different hats for different things. So, yeah, so that’s what we’re still doing and I think we’ll be doing it for another probably 18 to 24 months.

PIPA: And federal relief comes not just from FEMA. Kim Effler heard frustrations from the business community about the relief offered by the Small Business Administration, or SBA.

EFFLER: What I hear from my constituents, from my members is the red tape is ridiculous. When we think about getting a community back on its feet quickly, families are behind these small businesses. Children are relying on this income to be able to live and thrive and grow. And when you’re dealing with red tape it slows everything down on a ridiculous level.

[music]

PIPA: FEMA’s been a longstanding target for reform given the increase in natural disasters and the amount of federal money supporting relief and recovery. Soon after taking office in January, President Trump issued an executive order that directed a review of its processes and effectiveness. Kristi Noem, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, has publicly suggested abolishing the agency. Actions by the Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, have affected staffing and programs.

And there’s also been bipartisan legislation to reform FEMA, proposed by the chair and ranking member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, to simplify assistance and speed relief to disaster survivors.

All of this raises questions about what will happen in western North Carolina during its road to recovery.

[sounds of birds; outdoors]

[22:55]

MCDOUGALD: Yeah, this is Curtis Creek and it’s a great fly fishing resource. It’s great swimming holes. It’s, you know, you’ll see people and families, you know, here after they go mountain biking or hiking just playing in the water.

Yeah, if we were to continue to drive up Curtis Creek, or if we were to go up, uh, Catawba up the Catawba River, you would see people that are still parking on one side of the creek and walking their groceries across, you know, foot bridges to their homes.

Yeah, and then any, any place that you see a camper around here people are living, you know, those are people that were displaced. So if you see a camper in somebody’s front yard or just a camper sitting in a lot somewhere, that’s where somebody’s living.

[sound of water rushing]

PIPA: We took a walk with Jason McDougald to this creek in the Pisgah National Forest near Old Fort. It’s an important place to him. It’s where they built the first six miles of trail, with a dedicated and roomy parking lot, which is a rare thing in the mountains. That combination made it very popular and served as proof of concept, bringing new visitors to these mountains. And it showed how the outdoor economy could help the town thrive.

But as we heard earlier, Hurricane Helene took out the bridge connecting the parking lot to the rest of the trail, flipping it upside down and moving it downstream.

[24:23]

MCDOUGALD: I intentionally didn’t come out here. I just didn’t want to see it, honestly. And it was probably early December before I, I came out here. We had an actual official visit from representatives from the Forest Service that wanted to come see it. And, I mean, Stephanie and I were here giving a tour and she started tearing up and I couldn’t look at her ‘cause then I would start tearing up.

[music]

[24:50]

SWEPSON-TWITTY: So I would say that the storm certainly decimated, devastated our town. There is no doubt about that. That we are a good 60 months from any type of recovery from this storm, particularly economically.

The trailhead is one of those areas that was absolutely overcome; I mean, decimated to the point that no one can be there except the engineers that are re-developing the trailhead.

PIPA: Kim Effler at the Chamber of Commerce pointed out that extended closure of parts of the 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway—the National Park System’s most visited feature—has presented an economic challenge to many places in the region. The Parkway suffered widespread damage from Helene and it’s reopened in spots. But in North Carolina, several sections are still under repair. Mount Mitchell State Park, in Old Fort’s vicinity and home to the tallest mountain east of the Mississippi River, remains closed indefinitely because of the Parkway damage.

[26:08]

EFFLER: People come from all over the world to drive on the Blue Ridge Parkway. It’s nostalgic. It’s mysterious. It’s really an asset that we probably didn’t realize was such an asset until Helene illuminated the need for this road, and its visitors and the people that come here to enjoy it every day.

The Parkway is truly a lifeline to the small communities that are connected to it. Every day, people are coming to visit us and they’re headed to the Parkway. And we have to turn them around and tell them that they can’t, they can only jump on a very small section of the parkway.

So as far as policy issues or policy support from Washington, D.C., that is one that we’ve been very passionate about.

PIPA: As Kim sees it, one of the complicating factors is that small businesses don’t have many options when it comes to recovery from disasters.

EFFLER: I think the federal response for support in a town of less than 5,000 people needs reform. The federal response to small businesses, and newly formed small businesses have to be included in that, is really unacceptable. I think that the answer lies in creating some sort of a forgivable loan or a forgivable grant. I tend to favor a forgivable loan because there’s a due diligence process there when an applicant is applying for a loan.

We’ve been able to produce very small grants, very small grants, $5,000, $10,000 grants on a local level. But disaster relief for small business now is almost impossible. Many of the businesses only were given one option to apply for an SBA loan, but if they had a COVID SBA loan, they were immediately rejected for another SBA loan. We saw so many GoFundMe’s pop-up because people were that desperate for help.

PIPA: One of those business owners pursuing crowdfunding, in addition to government help, was Chad Schoenauer at the Old Fort Bike Shop.

[28:25]

SCHOENAUER: I started up a GoFundMe, and that was successful. I’ve also, fortunately, been able to access a number of grants to help my business. I had over two months of downtime with no revenue. And bills are bills, they gotta get paid. And so I was able to do that.

And then the longest effort that I faced was obtaining a SBA loan. The restructuring of the SBA, we’ll call it, caused my loan, which should have been closed in January, to be held up for five months. And that was another test of patience.

Combined with the uncertainty of the current administration and so forth, the tariff situations and all those market factors coming in, I am sitting at probably what would be typical in retail and business—I’ve heard numbers of around 30% year over year decline. And that is kind of where I’m at, coupled with the hurricane. So I, I’ll take it. I mean, it could be way worse for me.

Now in turn, I have been able to help out with fundraising for other folks. And gladly have done that so that everyone can benefit. I’ve also sat on a community board for grant and funding approval. And this is all done anonymously.

[music]

But I’ve seen the effects of that grant money making it to the right people here in Old Fort that want to still live here, that want to get out from underneath a mortgage for a home that’s disappeared.

PIPA: Everyone I talked to in Old Fort is committed to this place and its future. Camp Grier and Eagle Market Streets are still working on two major projects they had in development before the storm, estimated to bring $30 million in revenue to the town each year.

Eagle Market Streets’s project is the Catawba Vale Innovation Market. They hope the 60,000-square foot vacant commercial warehouse in downtown Old Fort will become a mixed-used facility with retail shops, a film studio, a restaurant commissary kitchen, meeting and conference rooms, maker space, and more.

Stephanie Swepson-Twitty is eyeing January 2026 to start construction.

[31:02]

SWEPSON-TWITTY: And we’ve been working on this project for about three years now. That kind of achievement is a byproduct that we didn’t think would happen post-Helene. But, you know, we’ve, we’ve managed to reshuffle the cards. I like to say that that Eagle’s greatest strength is the power of the pivot. We have, with this project alone, had to pivot at least three times.

EFFLER: We have married a project with Stephanie’s project, the Catawba Vale Innovation Market. The Chamber of Commerce is working to create a small business incubator right here in the heart of downtown Old Fort. Our small business incubator would be the first in a three-county region. I always say, McDowell County is known for manufacturing. Well, let’s manufacture business.

Statistically, one in three businesses fails in the first three years. So let’s beat those statistics. Let’s defy the odds. And let’s create an incubator where small business can come, learn everything about business, in two years graduate with a strong foundation for success. That’s all happening in the heart of downtown Old Fort.

PIPA: As for the trail system, progress has been steady but slow. In December of 2024, Congress passed the American Relief Act, which provided over $2.5 billion for the National Forest system. The U.S. Department of Agriculture plans to use 80% in association with Hurricanes Helene and Milton.

[32:51]

MCDOUGALD: Forest Service roads are still closed. Bridges are still out. There’s trails that have slides across ‘em that we have to go in and repair. So we’ve gotten about half of what we want to get opened reopened.

But we’re hoping, and our fingers are crossed, that that paperwork will be done soon and that we’ll be able to get back into the forest and continue to repair those trails and roads and bridges, ‘cause they’re really critical to the economy here. I mean, I, you know, the way I describe it is, like, each one of those businesses is like a little tree, like a little sapling. You know, it’s roots aren’t very deep. It’s kind of already just barely hanging on. And so we really need to get people coming back to Old Fort and to western North Carolina.

PIPA: The region still needs plenty of help with debris removal and rebuilding roads and bridges. This will help bring visitors back.

[33:44]

MCDOUGALD: You know, I think if people are trying to plan a vacation and they’re looking at coming to western North Carolina, do they wanna spend a couple grand to go to a place that still has pretty significant damage from a storm like Helene? So I think they’re choosing to go other places. You know, I think the state, North Carolina Department of Commerce and Visit NC, are doing a great job of trying to promote the region and invite people back. You know, our governor was just on Colbert basically saying the same thing. So I think those efforts are helping.

But in reality, it’s really we have to get all this debris removed and so that it doesn’t look like a, you know, a disaster zone and then, you know, build back smarter so that the next time, you know, we don’t have this extensive of damage.

PIPA: Yes, remaining debris still needs clearing, and full recovery will take time. During our conversation, Stephanie estimated it would take 60 months. But from my perspective, the debris distracts the eye from the beauty that remains—the beauty not just of the natural surroundings, but of the civic and community renewal driven by these people who love their place so much.

[35:00]

EFFLER: Helene may have been a gut punch, but we are back on our feet and we’re ready to continue the growth and the success. And the key to all of the success are the strong partnerships and the people like Jason and Stephanie and I that believe in the passion and that this is the right place. It is the right place for the work that we’re doing. The real estate will grow; the investment will come. But at the heart is the forest, right? the natural assets, and then the people that love this community.

SNYPES: What I would like to see for the town of Old Fort is to pick up where they left off. I would like to see the mountain biking and the hiking and the outdoor opportunities to continue. I want to see those new businesses continue to come in and thrive. I want to see Old Fort become a destination but not overwhelm us.

[36:04]

MCDOUGALD: Our vision for Old Fort, I think collectively, is just that we do outdoor recreation, community development different than it’s been done before.

[music]

And that it’s the best example of how to do it justly and sustainably. And, you know, you’re essentially trying to create that perfect economy. Right?

And so we want to continue to kind of be a model for how to think holistically about community development and workforce and housing and all those things. But, I mean, ultimately turning Old Fort into that kind of vibrant, kind of campus-like environment, like you can be here and not need to touch your car, you know, which is really unique. And so kind of making it a bikeable, walkable, vibrant space.

[37:03]

EFFLER: Everything has to matter in a town like Old Fort. Every amount of energy expended has to matter in a town like Old Fort. And when like-minded people come together with the same passion and are striving for the same purpose, magic happens. Big magic happens.

PIPA: As Old Fort was weathering the economic changes of the past couple of decades, Hurricane Helene was an unanticipated disruption of unimaginable ferocity. And yet, powerful as it was, it has not vanquished the vision, the commitment, and passion that these leaders have for Old Fort’s future … and its present. You don’t need to take my word for it—if you have the chance, I know they’d welcome a visit so you can see for yourself. No matter what, I’m sure they’re thankful for you listening to their story.

…

Reimagine Rural is a production of the Brookings Podcast Network.

[music]

My sincere thanks to all the people who shared their time with me for this episode.

To provide further policy insights based on this episode, we also publish a Q&A with an outside expert on the Brookings website. You can find the link in the show notes.

Many thanks to the team who makes this podcast possible, including Fred Dews, supervising producer; Molly Born, producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video manager; Zoe Swarzenski, senior project manager at the Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings; Adam Aley and Kevin Martinez, also in the Center for Sustainable Development; and Junjie Ren, senior communications manager in the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings.

Also, my sincere thanks to our great promotions team in the Brookings Office of Communications and Global Economy and Development. Katie Merris designed the beautiful logo.

Finally, support for this podcast is provided by Ascendium Education Group. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication or podcast are solely those of its authors and speakers, and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or its funders. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

You can find episodes of Reimagine Rural wherever you like to get podcasts and learn more about the show on our website at Brookings dot edu slash Reimagine Rural. You’ll also find my work on rural policy on the Brookings website.

If you liked the show, please consider giving it a five-star rating on the platform where you listen.

I’m Tony Pipa, and this is Reimagine Rural.

More information:

- Listen to Reimagine Rural on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

- Find out more about the Brookings-AEI Commission on U.S. Rural Prosperity.

- Discover more research on Reimagining Rural Policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastRestoring outdoor recreation in Old Fort, North Carolina, after Hurricane Helene

Listen on

Reimagine Rural

July 29, 2025