Introduction

Medicare premiums pose a significant burden on low-income older adults. Current policies meant to alleviate those burdens do not work well. This issue brief proposes a new way of lowering those burdens for millions of older adults and illustrates how this can be done in an efficient manner without adding to the federal budget deficit. This proposed policy will also eliminate situations where small changes in income or aging into Medicare generate a large difference in government assistance.

In 2022, the poorest one-fifth of older adults live below 151% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) and have an average family income of $14,067.1 Over 50% of these people live alone and rely on Social Security, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), or both, for a large portion of their income.

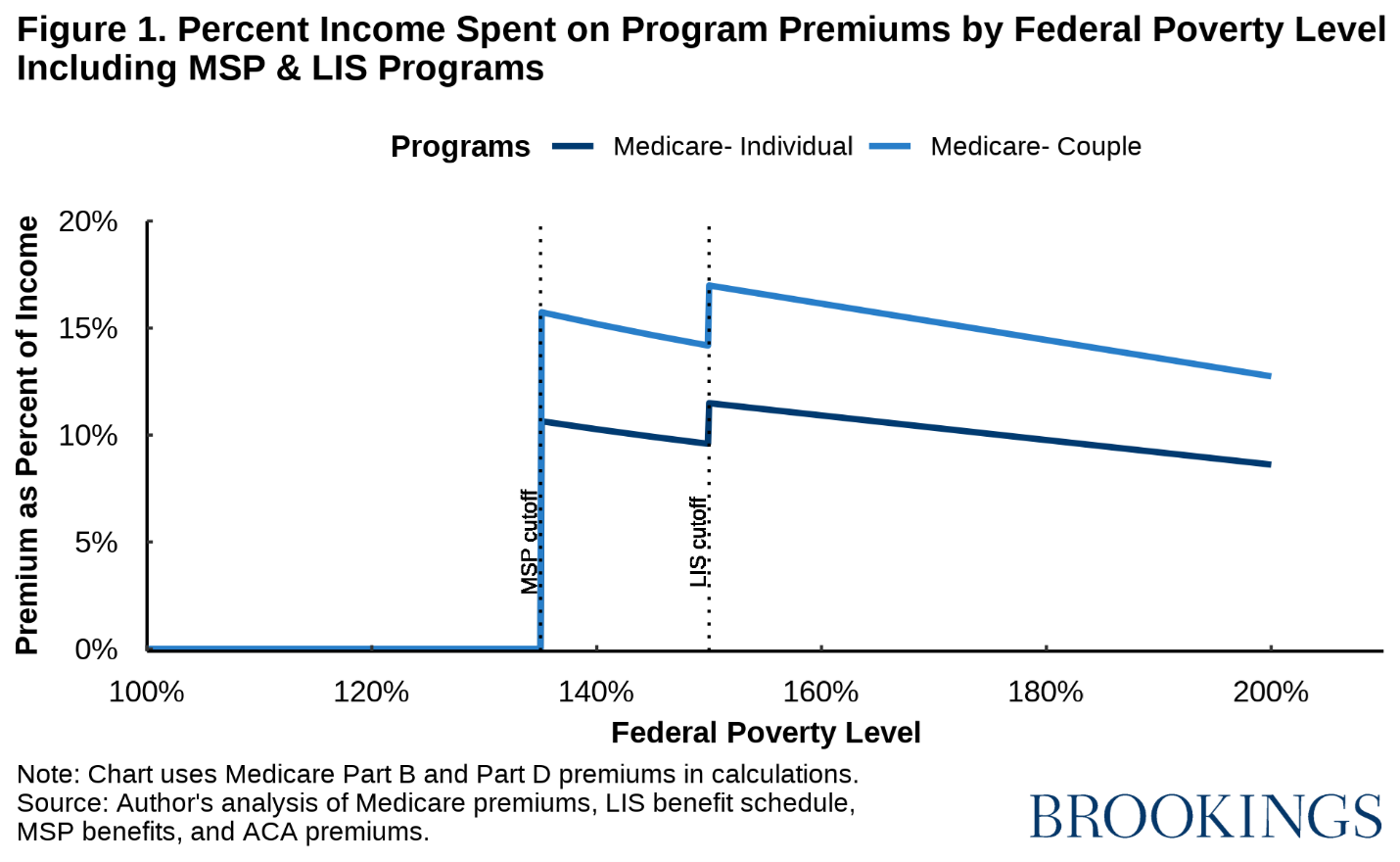

Medicare premiums are large relative to these beneficiaries’ incomes. For a single beneficiary with income at 150% of the FPL,2 premiums are over 11% of their annual income. For a couple at 150% of the FPL, premiums are equal to 17% of their income. Given the modest income of these households, these premiums may constitute a substantial burden and force them to cut back on other valuable spending, both in the health care domain and beyond.

Current law aims to reduce Medicare premium burdens for low-income recipients through the Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs) and the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS). However, because of low participation rates and limited eligibility, these programs leave many of the lowest-income Medicare beneficiaries with substantial premium burdens. Furthermore, a very small change in financial circumstances can lead to large differences in government assistance.

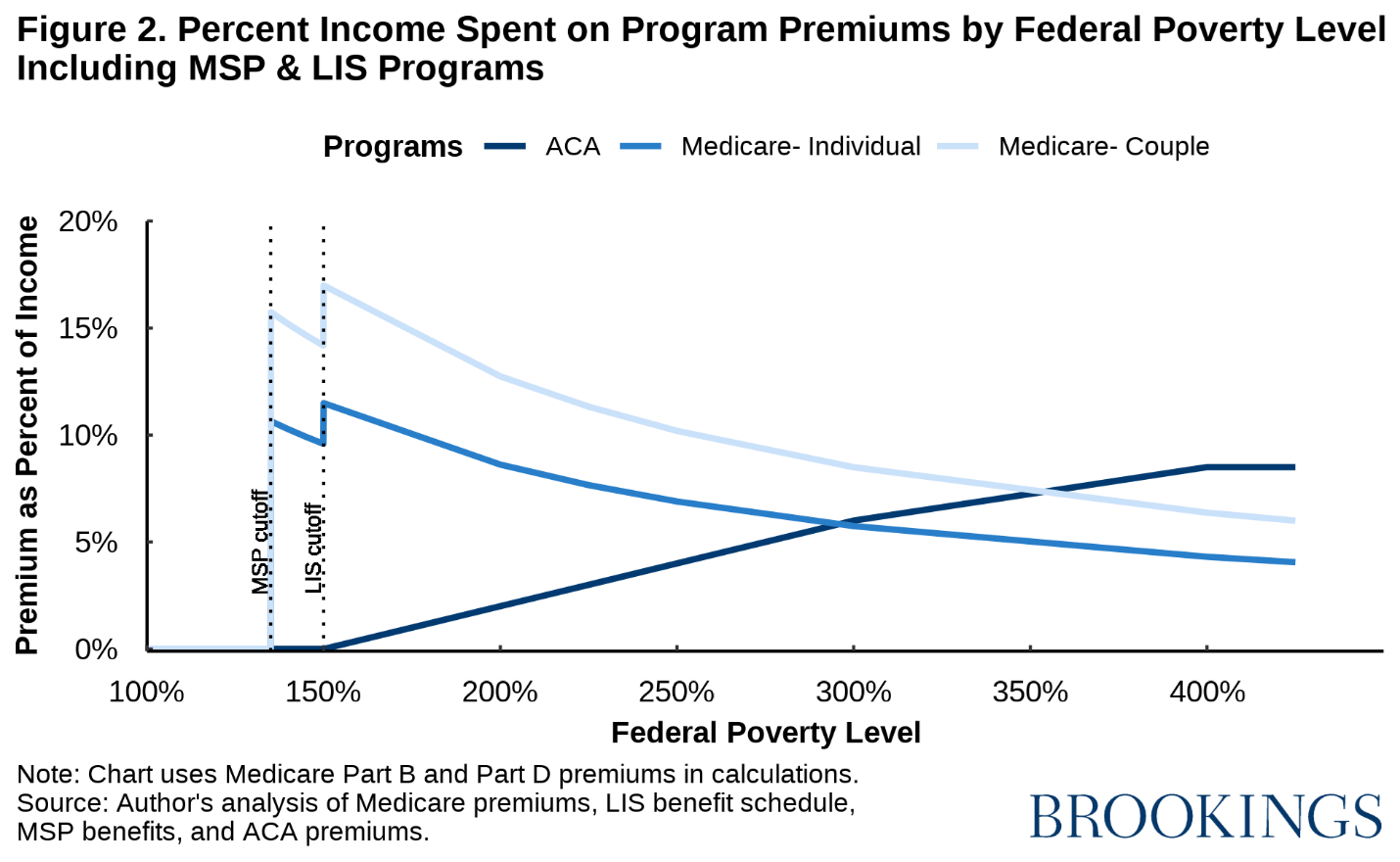

Federal policy is notably more generous to low-income non-elderly people who buy their coverage on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces. In Medicare, all assistance in helping pay Part B premiums ends at 135% of FPL. For non-elderly people eligible for subsidized coverage through the ACA Marketplaces, no premiums are required until 150% of the FPL. As a result, an elderly couple at 200% of the FPL pays $5,026 (12.7% of income) in Medicare premiums while a couple eligible for subsidized Marketplace coverage with the same income pays $789 (2% of income).

We propose to replace the MSPs and LIS with a new federal program that would more generously subsidize Medicare Part B and Part D for low-income Medicare beneficiaries. This program would have higher participation rates than the MSPs and LIS and extend eligibility for subsidies to substantially higher income levels. The details of this program are explained in the following sections of this issue brief.

We begin by examining the premiums owed by Medicare beneficiaries. In this analysis, we focus only on Medicare Part B – which covers physician and outpatient services – and Part D – the prescription drug benefit. We do not include Part A – the hospital insurance program – in this analysis because almost all Medicare beneficiaries do not pay premiums for Part A. For 2024, the Part B monthly premium is $174.70 and the base Part D monthly premium is $34.70.3 These premiums total $2,513 for an individual and $5,026 for a couple annually. Therefore, for an individual Medicare beneficiary whose income is at 175% of the FPL, these premiums amount to 9.8% of their income. For a couple on Medicare whose income is at 175% of the FPL, these premiums amount to 14.6% of their income.

The MSPs and LIS

The MSPs and LIS are designed to help alleviate this burden for Medicare beneficiaries with the lowest incomes by paying these premiums for eligible beneficiaries.4 There are three main MSPs: the Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) program, the Specified Low-Income Medicare Beneficiary (SLMB) program, and the Qualified Individual (QI) program.5 Each of these programs cover the Part B premium for beneficiaries whose income is at or below 135% of the FPL, but they differ in benefits and eligibility requirements. All have stringent asset limits. The LIS program covers the Part D premium for eligible individuals who fall under 150% of the FPL. This program also has stringent asset limits. The eligibility requirements for the various MSPs and the LIS program are described in greater detail in the Appendix.

Although these programs were created to address the financial burden that Medicare premiums pose to low-income Medicare beneficiaries, there are two major issues that prevent the MSPs and LIS from achieving these goals: low participation rates and limited eligibility.

Low participation rates

Low participation rates are mostly a result of the complex administration of these programs. The MSPs are administered through state Medicaid programs, resulting in inconsistencies with eligibility and program details across states, such as varying state policies for counting assets. Some factors affecting the participation rates of MSPs are asset limitations, the lack of knowledge about these programs among potentially eligible participants, and a burdensome application process.

According to one study, participation rates for the MSPs in the late 2000s were 53.1% for the QMB program, 32.2% for the SLMB program, and only 15.1% for the QI program. However, there were issues with this study that lead us to believe that these participation rates are not accurate estimates,6 and we have reason to believe that the true participation rates are higher than these estimates. For example, California program officials commented that their participations are relatively high compared to the rates in the study cited above.7 Administrative data on MSP enrollment also shows large increases in overall enrollment from 2007 to 2022. However, because of lack of data, we cannot accurately estimate the participation rate in the MSPs.

The LIS program is administered federally by the Social Security Administration (SSA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). According to the National Council on Aging, the LIS program’s participation rates vary widely depending on whether or not an individual is automatically eligible for the program. In 2014, the participation rates for those automatically eligible were near 99% whereas the participation rates of those not automatically eligible were under 33%. More details on LIS’s automatic enrollment policy can be found in the Appendix.

CMS recently proposed to begin using LIS eligibility and enrollment data to automatically enroll eligible individuals into the MSPs. There are over 1.1 million individuals who are enrolled in the LIS and seemingly eligible for the MSPs, so this proposal could substantially increase MSP enrollment. Although this rule would increase participation in the MSPs, there would still be many individuals who qualify for the program but would not be enrolled.

Limited eligibility

While the LIS and MSPs have low participation rates, a more fundamental problem is limited eligibility. All assistance for Part B premiums ends after 135% of the FPL. This leads to a significant difference in premiums faced by Medicare beneficiaries whose income falls on either side of this cutoff. An individual with income at 135% of the FPL, or $19,683, faces premiums of $0 because of the MSPs and LIS programs. However, an individual whose income is just above the income cutoff at 136% of the FPL, or $19,829, now has to pay the full premium for Medicare Part B, which is $2,096, or 10.6% of their annual income. The annual income difference between these two individuals is only $146, and yet they face extremely different premiums for the same health insurance. This same issue occurs at 150% of the FPL, when assistance from the LIS program ends. These cliffs are even larger for couples who are enrolled in Medicare, as Figure 1 below demonstrates.

The sharp cutoff of the MSP and LIS subsidies are problematic for two reasons: 1) individuals on either side of this cutoff have relatively equivalent incomes but face extremely different Medicare premiums, and 2) for some individuals, income fluctuates from year to year. Therefore, an individual whose income is close to the cutoff could switch between qualifying for MSP assistance in one year and face the full Part B premium the next year, a financial shock that may be hard for some families to absorb.

Comparison to ACA Marketplace subsidies

Given the significant burden imposed by Medicare premiums on low-income older adults, it can be instructive to compare the Medicare Part B and D premiums of Medicare beneficiaries to the premiums faced by people enrolled in subsidized coverage through the ACA Marketplaces with identical incomes and family size. Under current law, Marketplace premiums for the benchmark (i.e., second lowest-cost) silver plan are zero for anyone whose income is below 150% of the FPL and gradually increase as a share of income until income reaches 400% of the FPL, above which the premium is limited to no more than 8.5% of a household’s annual income.8 More details on the premium structure of the ACA program can be found in the Appendix.

When accounting for the MSPs, Medicare beneficiaries and Marketplace enrollees with incomes below 135% of the FPL pay the same premiums. However, individual Medicare beneficiaries whose income falls between 135% of the FPL and 300% of the FPL (an income of about $44,000) pay significantly more than low-income single Marketplace beneficiaries who buy benchmark coverage. For couples, Medicare beneficiaries pay more in premiums until 350% of the FPL or an annual income of about $69,000.

Due to significant differences in the structure of Medicare and the Marketplaces, raw premium comparisons likely overstate the degree to which Marketplace enrollees in these income ranges—and particularly Marketplace enrollees above 200% of the FPL—are better off. Notably, for people with incomes above 200% of the FPL, a Marketplace silver plan offers an actuarial value of only 70%, whereas the Medicare program has an actuarial value in the low-to-mid 80s, meaning that Marketplace enrollees in this income range can face greater cost-sharing. Some of these beneficiaries may also opt for Medicare Advantage plans that typically offer even lower cost-sharing, plus additional benefits, although such plans generally also impose more utilization restrictions. Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans alike typically pay lower prices for care, which further reduces cost-sharing. Marketplace plans also tend to offer relatively narrow networks, whereas traditional Medicare offers an extremely broad network of participating providers.

There are factors that push in the other direction as well. Medicare serves an older and disabled population with higher medical spending than the population served by the Marketplaces. People in traditional Medicare also lack catastrophic coverage (which Marketplace plans must provide), although many Medicare beneficiaries buy a Medigap insurance plan that provides such coverage (as well coverage of much other cost-sharing), albeit at an additional premium. Regardless, it is clear that simple premium comparisons like those we present here do not and cannot tell the whole story.

There may also be good reasons for policymakers to set different premiums in different populations. For example, insurance take-up has historically been incomplete in the Marketplace population, whereas it has been nearly universal among people ages 65 and older. If policymakers aspire to universal coverage, offering deeper subsidies in the Marketplace context may be necessary to achieve that goal.

Nevertheless, we see it as notable that Congress has made different choices about the level of premium assistance to offer Medicare beneficiaries versus Marketplace enrollees. Moreover, in our view, the premiums offered to Marketplace enrollees are more appropriate, at least at lower income levels.

This significant difference in premiums becomes very apparent to many new Medicare beneficiaries as they are required to switch from ACA plans to Medicare when they reach age 65. This leads to an issue which has become known as the “Medicare cliff.” For an individual whose income is at or below 150% of poverty and younger than 65, they face no premiums while they are covered by Medicaid or the ACA Marketplace. However, when those individuals enroll in Medicare – either by turning 65 or reaching two years after being found disabled, their insurance premiums jump from zero to over 10% of their annual income (Figure 2). State policymakers and advocacy groups are becoming more aware of this cliff.

Proposed solution

There are two approaches to addressing the issues of low participation rates and limited eligibility caused by the current structure of these programs: 1) modify the MSPs and LIS or 2) create a new federal program modeled after the current administration of the LIS program and the program that collects the income-related premiums (IRP) from high-income Medicare beneficiaries. We believe establishing a new federal program to subsidize Medicare Part B and Part D premiums to replace the current MSPs and LIS is the better choice. We reject the first option because addressing the problems we have identified would entail a large expansion of eligibility and major changes in how benefits are calculated. Even if the enhanced benefits were federally financed, this would place considerable administrative burden on states, which would likely pose both substantive and political problems.

This new program would restructure the Medicare Part B and base Part D premiums to be entirely a function of a beneficiaries’ income level. Like in the current Marketplace subsidy structure, no premiums would be required until income exceeds 150% of the FPL. After 150% of the FPL, the Medicare premium would be 9% of income above 150% of the FPL, up until the maximum premium. The maximum premium would be set to be equal to twice the current premiums, or $5,026 for an individual and $10,051 for a couple. When Part B was first established, the premium was equal to 50% of the cost. These maximum premiums would be reached at an annual income of about $77,700 (533% of the FPL) for an individual and above $141,300 (716% of the FPL) for a couple. As under current law, a higher premium will be charged for those at the highest end of the income distribution. However, when the current IRP is less than 50% of the actuarial value of Parts B and D of Medicare, the premium will be increased to 50%. For other beneficiaries that pay the IRP, those premiums will not change. Low-income Medicare beneficiaries would have their premiums lowered significantly, while some middle-income and upper-income beneficiaries over age 65 would pay more than under current law. Table 2 outlines the premiums this proposal would charge at different income levels.

Just like today, the Medicare actuaries would establish what the premium is for Parts B and D of the Medicare program as under current law. Then they would establish the 9% parameter to switch the premium from a flat dollar amount to a premium as a function of income. Like today, the premium will change each year including the 9% figure to maintain the 25% rule.9 But unlike current law, there will be much less concern about whether the Social Security cost of living adjustment (COLA) covers the increased Medicare premiums except when the COLA is zero or close to zero. For low-income beneficiaries, the COLA will always be larger than the increase in Medicare premiums because Medicare premiums have been significantly reduced. For most higher-income Medicare beneficiaries, the increase in their Social Security check will exceed the increase in the Medicare premium and if not, those individuals will have sufficient income to cover the additional cost of the Medicare premiums.

Asset limits would also be eliminated, which would both increase participation and eligibility by reducing barriers to receiving necessary help. The program would also include an automatic enrollment process for many participants, which is described in greater detail below. This automatic enrollment process would ensure that the program achieves near universal participation.

Administrative details

Anyone receiving aid from Medicaid, SSI, or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) would have their Medicare premiums set to zero. While SSA already has information on SSI enrollment, information on Medicaid and SNAP enrollment would be reported by states. Anyone who has a Medicare premium that is subtracted from their Social Security check would have their eligibility for the new program automatically assessed using income data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

About 9% of Medicare beneficiaries pay IRPs. The IRS electronically provides the SSA with tax information to determine which enrollees must pay the IRP. Extending this system to apply to all Medicare recipients should not create substantial additional administrative burden. Income would be taken from the same tax return that is used today to administer the IRPs. If there was no income tax return filed by a Medicare beneficiary, the IRS would share with SSA any form 1099 income reports for the beneficiary and the SSA would assume their income equals their Social Security and form 1099 income. The beneficiary’s Medicare Part B and D premium would automatically be calculated in accordance with the schedule described above.

In cases where no tax return was available, the SSA would check with the beneficiary and determine if the individual or couple had other income and require that this income be reported. If the individual or couple had income, the SSA would adjust the premium for the remainder of the year to ensure that the premium amount collected for the year is the correct amount. No adjustment would be necessary if the change in premium was less than $10 per month. As occurs under the current IRP rules, beneficiaries could also request that more recent income information be used.

There may be some individuals who would qualify for the program but do not have their premiums automatically subtracted from their Social Security checks. Those individuals would have to apply for assistance through an SSA-operated website. The website would evaluate their eligibility using SSA records on SSI enrollment, IRS data, and state-reported data on Medicaid and SNAP enrollment in the same way as beneficiaries who were enrolled automatically. In cases where the individual was enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan that charged a lower premium than the normal Part B and Part D premium, SSA would ensure that the premium subsidy provided did not exceed the actual premium.

Income in the previous year determines eligibility for this new federal program. By making income in the previous year the basis for eligibility, the reconciliation process that ACA beneficiaries are subjected to each year is avoided. At the time individuals reach 65 and become eligible for the Medicare program, eligibility for the new federal program is assessed given their Social Security benefit level and any non-employment income that will be received that year. Thus, when they are new entrants to the program, the income that will be received on a regular basis in retirement determines their income. For someone that applies mid-year, it is their income for the remaining months of the year that would be used to determine eligibility. Eligibility would be reevaluated each year using the same procedures.

The participation rate for this program should be nearly 100% because of the auto enrollment feature of the plan. Eliminating the MSPs will create a windfall for states and how that windfall could be utilized will be described in a later publication.

Impact10

The proposal would dramatically improve the well-being of low-income older adults and individuals with disabilities. We have simulated the proposal for individuals on Medicare who are 65 or over. Under this proposed premium schedule, we calculate that approximately 26.7 million Medicare-aged beneficiaries would be paying less than current law, and approximately 24.0 million Medicare-aged beneficiaries would be paying more. For example, in 2024, individuals with incomes less than $49,790 and couples with incomes less than $85,420 will be paying less for their Medicare premiums. We also calculate that this change would cost $40.0 billion to cover the lower premiums of those 26.7 million beneficiaries, but this new premium schedule would bring in $34.6 billion from beneficiaries paying more. Thus, this new premium schedule would not be fully funded and would have an overall cost of $5.4 billion. Our calculations do not include Medicare beneficiaries who are disabled and are only based on beneficiaries who are 65 years or older. We propose to increase the net investment income tax (NIIT) rate to make up the cost not covered by the increase in premiums. According to administrative data, there are 7.2 million older adults enrolled in the MSP programs. The federal government will now pay the entire cost of those beneficiaries and the states will reap an estimated $6 billion windfall.11 The increase in the NIIT and the amount collected from beneficiaries above 150% FPL will maintain the 25% rule.

Unlike current law, there will be no instances where Medicare premiums would change significantly with small changes in income. When Marketplace beneficiaries turn 65 and become eligible for Medicare, premiums for low-income beneficiaries also would not change significantly.

Conclusion

Premiums for Medicare Part B and Part D can pose a significant financial burden to low-income beneficiaries. The current policy solution for this issue is the MSPs and LIS programs. However, because of low participation rates and limited eligibility, we conclude that the current avenues do not adequately address the financial burden faced by Medicare beneficiaries with the lowest incomes. The current programs end all assistance at 150% of the FPL, leaving many Medicare beneficiaries facing premiums that total to be a significant percentage of their income.

The structure of the MSPs and LIS programs also lead to significant “cliffs” where individuals who have similar incomes face substantially different premiums depending on which side of the cliff they fall. The differences between the current ACA structure and the MSPs and LIS programs also lead to many individuals facing significantly higher premiums as they age into Medicare, even if their financial situation hasn’t changed.

The best way to reduce these burdens would be to create a new federal program that is structured to both increase participation rates through automatic enrollment and expand eligibility significantly past 150% of the FPL. This will lead to more low-income Medicare beneficiaries having access to help with paying their premiums and alleviating this large financial burden. This issue and solution deserve attention as it holds the potential to improve the well-being of millions of low-income Medicare beneficiaries significantly. It is critical that before 2026, the extension of the current ACA premium schedule is enacted and Medicare premiums for millions of low-income elderly individuals are lowered in a budget neutral manner.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors gratefully acknowledge comments from Matt Fiedler on an earlier draft. They also thank Chloe Zilkha and Caitlin Rowley for excellent research and editorial assistance.

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- Author’s calculations based on 2023 CPS ASEC data. We sort older adults into quintiles based on their family income relative to the relevant poverty level.

- Calculations in this issue brief are based on the 2023 FPL.

- Medicare Part D premiums depend heavily on the insurance plan a beneficiary is enrolled in. However, CMS sets baseline premiums every year, and we use this baseline in our analysis.

- This issue brief focuses on older adults since Medicare coverage broadly begins at age 65. Much of this issue brief also applies to low-income individuals with disabilities. Individuals with disabilities can receive Medicare two years after becoming eligible for Social Security benefits.

- We do not include the Qualified Disabled and Working Individuals (QDWI) program because it only deals with Part A premiums, which are not important to this analysis.

- The study did not account for beneficiary assets and counted some people who clearly were ineligible as eligible, and it did not fully account for Medicare beneficiaries who were getting supplementary coverage from employers.

- Private communication with California program official.

- This analysis is based upon the current ACA premium schedule which was set into effect by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, but will revert back to the original ACA structure in 2026 if the current law isn’t extended.

- See Appendix for further details on the 25% rule.

- All values in this section come from authors’ analysis of CPS data and current policy unless otherwise noted.

- This estimate is based on an average federal medical assistance percentage as found here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Reducing premiums for low-income Medicare beneficiaries

Millions would benefit from a new federal program

February 15, 2024