The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted almost every aspect of daily life but presents an added burden on families with young children. Closures of preschools and child care centers have put a strain on caregivers to meet all of the developmental needs of children at home. This, in combination with economic instability and social isolation, is a recipe for toxic stress, which can have long-term negative effects on brain development and health.

Even before COVID-19, 8 out of 10 children in low-income countries did not have access to pre-primary education. We are missing a critical window of opportunity to build the foundational skills that set young learners on a path to success in school and beyond.

Recently the Center for Universal Education (CUE) hosted a virtual roundtable discussion that examined the current state of pre-primary education around the world—who has access, how it is funded, and what “quality” means—and what is needed to prioritize and accelerate progress toward providing quality universal pre-primary education for all. Joan Lombardi, long-time adviser of CUE and senior scholar at the Center for Child and Human Development at Georgetown University, moderated the discussion, and I provided opening remarks.

The discussion kicked off with brief remarks from leading global organizations, including UNESCO, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), with an update on their efforts to highlight and both protect and increase public funding for pre-primary education .

- UNESCO shared a preview of their soon-to-be-released study “The Right to Free Pre-Primary Education,” which aims to establish pre-primary education as (at a minimum) a free, one-year program for children in all countries as an important step in shaping the policy landscape and legal provisions surrounding pre-primary education mandates and implementation.

- UNICEF has responded to the pandemic by addressing the immediate needs of parents and caregivers to support holistic development and learning at home, while at the same time supporting governments and employers in developing longer-term recovery plans. UNICEF’s recent report provides an economic argument for investing in pre-primary education based on a benefit-cost analysis in 109 developing low- and middle-income countries and territories.

- The World Bank is working across sectors to support parents and caregivers to reach the most vulnerable children and ensure that government efforts prioritize early childhood development during the pandemic. A recent World Bank blog highlights the risk to underinvesting in the early years right now and the many opportunities to support children’s learning in innovative ways as part of the pandemic response and recovery.

- USAID has a new working group on early childhood development and pre-primary education that is currently conducting a literature review to guide low- and middle-income countries on best practices for implementing high-quality pre-primary education.

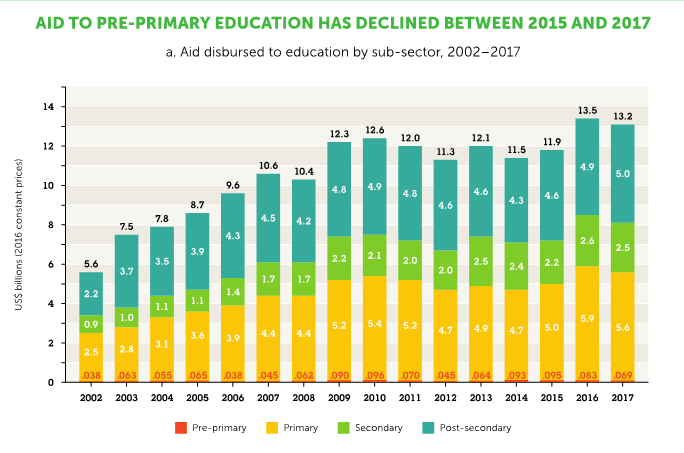

A constant thread in the conversation focused on the lack of tangible investments in pre-primary education. An analysis of donor spending by Theirworld reported that while overall aid to education has been growing, the aid for pre-primary has been uneven over the past decade and has not increased at the same pace as other sectors. Looking at some of the more recent figures, like below, pre-primary’s share of education aid declined from 0.8 percent in 2015 to 0.5 percent in 2017.

The roundtable also benefited from the perspectives of representatives from various regions of the world including Africa, The Asia-Pacific, and Latin America. Concern was raised about the lack of access to pre-primary education in the African region and the need to include comprehensive services such as health and nutrition. Looking at the Asia-Pacific region, all of the 49 countries offer one to four years of pre-primary education, but less than half offer one year free, and only eight make it compulsory, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database (accessed June 2020). Many Latin American countries have made significant strides in access to pre-primary education, so the conversation has turned to the need for quality education, with a focus on teacher-child interactions, consistent monitoring and evaluation of classroom practices, and promoting communication between public and private sectors.

Joan concluded the meeting with a call for action to continue to raise public awareness about early education and emphasized the critical importance of increased investments.

With crisis comes opportunity—an opportunity to reduce inequalities, optimize human capital, and contribute to healthy and prosperous futures—and this discussion was an important step forward in reimagining what pre-primary education can and should be.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Pre-primary education around the world: How can we provide quality universal early education for all?

November 3, 2020