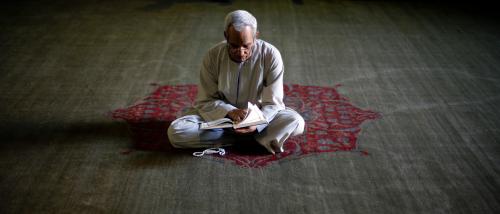

The following post is by Nael Masalha, a longtime figure in the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood and the director of the Al-Essra Hospital, and previously a member of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Executive Bureau. Shadi Hamid follows, asking some clarifying questions. Masalha then responds.

Jump to Shadi Hamid’s response »

Jump to Masalha’s response to Hamid »

The longstanding stability between Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood and the Jordanian regime has often been interrupted by changes in approaches and strategies on both sides. We are in one of those fluid phases right now. In his contribution to the Brookings “Rethinking Political Islam” initiative, Brandeis University’s David Patel also addresses the effects of the Arab Spring—especially after Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood won in Egypt—which led to a series of internal revisions and changes within Jordan’s Islamic movement. That said, there hasn’t been much fundamental change in how the movement and the regime perceive each other. I do agree with Patel that the relationship will neither end completely, nor change dramatically.

Speaking as a long-time figure in the Brotherhood, there are, in my opinion, several reasons for the recent divisions with the Jordanian Brotherhood’s ranks. The first has to do with Hamas’s complicated and controversial relationship with the Islamic movement in Jordan. Hamas changed its organizational structure and strategic vision to more effectively deal with both the Jordanian regime and the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood, with which it has a deep ties (irtibat al-’adawi). These changes began in earnest after Hamas moved its leadership from Jordan to Syria in 1999.

Hamas has now turned into an organic and independent organization. These developments started in early 2001 and ended in 2008, which is when Hamas became a regional organization directly affiliated with the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau rather than its formal leadership in Jordan.

After this organizational independence solidified, Hamas found itself looking for a strong base of support for the movement, one deeply rooted in society that would allow it to operate in broad daylight rather than in an opaque manner. Thus, Hamas looked strategically at Jordan for its deeply rooted Palestinian presence and the growth potential of its population. According to some estimates, up to 60 percent of Jordanians are of Palestinian origin. Also, the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan and its affiliated institutions—including the Islamic Action Front—have traditionally enjoyed considerable financial and political resources. Therefore, it was both natural and easy to penetrate the Brotherhood’s organization given Hamas’s capabilities. Namely, its overwhelming popularity as a result of its repeated victories in Gaza, its steadfastness in Palestine within and beyond the Green Line (pre-1967 borders), and the sympathy and support it enjoyed from Palestinians in the diaspora and by Arab Muslims across the globe.

There arose a change in the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood’s leadership in 2008, in conjunction with Hamas’s breakaway from the Brotherhood’s leadership in Jordan. This amounted to a coup within the Brotherhood, which came about as a result of the Brotherhood’s leadership crossing all the red lines that had come to define relations between Islamists of Palestinian origin and those of Jordanian origin. Of particular significance was the appointment of a General Overseer for the Brotherhood and a secretary-general for the Islamic Action Front—both of Palestinian origin—who were well known for their loyalty to Hamas. More important, however, was Hamas’ ability to penetrate and consequently exert control over all aspects of the Jordanian Brotherhood. In so doing, they were able to make it seem that if you were not with Hamas, you were against the Islamic movement overall, or that if you weren’t for the Palestinian cause, you were for the Jordanian regime and its various agencies.

Hamas worked in an organized fashion within the Jordanian Brotherhood and its affiliated institutions, injecting huge amounts of money to recruit members—some of Jordanian origin—who became increasingly active and engaged in the Brotherhood’s projects. This resulted in Hamas consolidating control over the Brotherhood’s organization in Jordan. Longtime Brotherhood members of Jordanian origin started to become nervous after sensing that the group’s new leadership was adopting a non-Jordanian, unpatriotic agenda. They felt that the leadership was using the members as pawns to implement the policies of Hamas, which had begun to interfere in every detail.

This situation—which started worsening during the Arab Spring—led to the following splits: first, a group of first- and second-rank Brotherhood leaders put forward the Jordanian Building Initiative, known popularly as Zamzam. Zamzam concentrates on presenting a project of national reform based on citizenship; loyalty to Jordan (while retaining an Islamic identity in line with the Jordanian constitution); the acceptance of others regardless of religion and political orientation as long as they accept joint action within a national inclusive framework; and a desire to maintain a collegial and non-confrontational spirit when interacting with any party, including the Jordanian regime.

This approach was met with harsh rejection by the Brotherhood’s leadership, which, as discussed earlier, had come to represent Hamas’s interests. Consequently, the leadership instructed its affiliated writers—who enjoy financial and logistical support from Hamas—to attack the idea and link it to being a scheme of Jordanian intelligence, and subsequently claim that Zamzam was a means by which to bring the Islamic movement under state influence.

Second, because of adverse reactions to the Zamzam initiative within the broader Islamic movement, another group of Brotherhood members tried to put forward a reform project of their own, leading to the formation of the “Group of Elders” (Majmu’a al-Hukama’). Comprised of first-generation former Brotherhood and Islamic Action Front leaders, this new body could also claim a significant membership of Palestinian origin. The Group of Elders warned against the Brotherhood leadership’s behavior, stating that it was putting the group and its future in Jordan at risk, and calling for its dismissal and restructuring, resulting in the Group of Elders coalescing around a centrist position. They proclaimed that they lost hope in the leadership of the Brotherhood and subsequently mobilized supporters to announce the establishment of a new party. This group has been revitalizing its internal procedures and engaging in discussions with many parties—including those behind the Zamzam Initiative. However, Zamzam’s leadership rejected the idea of a merger with the Group of Elders. Zamzam ultimately put the issue to rest by registering a new party of their own called the National Congress Party (Hizb al-Mu’tamar al-Watani). As of the time of writing, the party is still in its early stages, with roughly 20% of its members coming over from the Jordanian Brotherhood, and 80% from elsewhere.

Third, the establishment of a new organization called the Muslim Brotherhood Society (Jam’iyyah al-Ikhwan al-Muslimeen)—with the installation of Abdul Majeed Thneibat as the society’s General Overseer (al-muraqib al-’am al-ustadh)—was a significant development. The society was established following conferences discussing the Brotherhood’s reform efforts. A chorus of voices then emerged calling for the dismissal of the then-General Overseer Hammam Said, a revision of the Brotherhood’s organizational statutes, and a restructuring of its leadership.

During these developments (which were being watched closely by the Jordanian government), a discreet meeting was held in January 2015 between Abdul Majeed Thneibat and His Majesty King Abdullah II at the Royal Palace. According to Abdul Majeed Thneibat, His Majesty the King expressed concern that Arab leaders would bring up the case of the Muslim Brotherhood in member states, including Jordan, during their next meeting—which was scheduled to be held in early March. He added that many wanted to designate the Muslim Brotherhood as an illegal terrorist group within Arab League member states. In this meeting, a request was made to help the Jordanian state avoid any embarrassment, especially since the Brotherhood had a long history of legal participation in Jordan, to the point where it had its own Jordan-specific slogans. The request was clear: the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood had to rectify its legal status in terms of its registration permit to continue operating according to the current Jordanian laws in force. It also had to change its founding statutes, which asserted the group’s organizational ties with the Brotherhood in Egypt. Abdul Majeed Thneibat invited a group of Brotherhood members and explained the situation. They discussed possible ways forward, arriving at a decision to register the group under the name “Muslim Brotherhood Society,” and to appoint an interim leadership for six months until elections were held to choose a new leadership. They would then be in compliance with Jordanian law.

All in all, there are four organizations or groups that have emerged from the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood thus far:

- The old or parent group led by Hammam Sa’id

- The Muslim Brotherhood Society led by Abdul Majeed Thneibat

- The group functioning under the auspices of Zamzam and its attendant National Congress Party

- The Group of Elders, which has recently announced the formation of a new political party under the name of the Partnership and Rescue Party (Hizb al-Shiraka w’al-Inqadh).

The Current Reality

When Zaki Bani Rashid — then the Brotherhood’s deputy General Overseer—was released from prison in 2016, he put forward an initiative based on the principles of Zamzam to contain the ongoing division, but it was shrouded in uncertainty and mistrust and was thus met with extreme caution. The proposal promoted cooperation across the range of views within the organization, as well as dialogue between the various factions.

To the ever-watchful Jordanian government, the Islamist scene today is in a state of disarray and division, making it especially vulnerable. The government is attempting to perpetuate this weakness in any way possible to keep the Islamic movement weak, rather than risk the likely pricier option of attempting to eliminate it.

Consequently, this weakness and division is reflected in the Islamic movement’s other social, political, advocacy, and union initiatives. It has also lowered public confidence in its ability to serve the nation, rectify the culture of corruption, or address the general weakness of civil society.

The Vision

The overall situation in and around Jordan—especially given the presence of Daesh (the Islamic State) at its borders, the failure to reach a fair solution to the Palestinian conflict, and the region’s preoccupation with different and sometimes conflicting agendas—keep each party within Jordan and within the Islamic movement in a near-constant state of suspense. The state, taking advantage of the situation, is trying to weaken the Islamic movement’s presence and activity. In response, the movement is trying to endure, while sometimes overlooking the gravity of the situation, waiting for things to pass like a summer cloud. This paves the way for other groups—such as Zamzam—to fill political vacuums and address blind spots. This gives them a better chance, especially given that Zamzam’s ideology is a departure from the path of da’wa (religious education and advocacy), which the parent Muslim Brotherhood group, the Muslim Brotherhood Society, and the Group of Elders have all retained.

Shadi Hamid responds:

I have two quick comments and questions.

First, would it be possible for you to address David Patel’s thesis that “what is almost always described as an ideological divide is better understood as an ‘ethnic’ or ‘communal’ one”? It sounds like you would agree with this to an extent, but I would be curious to hear a bit more, including on the question of whether ideology and religious and moral issues are important in understanding tensions between “hawks” and “doves” within the Muslim Brotherhood. Also, you focus on the question of Hamas, which is obviously very important, but what about divides over how confrontational the Jordanian Brotherhood should be toward the government? There’s the perception among some in the old Hammam Sa’id–led Brotherhood that the new (breakaway) Muslim Brotherhood Society has been too deferential toward the monarchy and hasn’t pushed hard enough for political change. To what extent is this a legitimate concern?

Second, could you say a bit more about the effects of the military coup in Egypt on Jordan’s Islamic movement? How much did what was going on in Egypt and the fear of a repeat scenario drive the new strategy of those like Zamzam, the Muslim Brotherhood Society, and the Group of Elders?

Nael Masalha responds:

On your first question, I think that the ideological and religious dimensions of the orientation of the group’s doves and hawks are completely different from the regional dimension.

Brotherhood members of Palestinian origin do not differ on the need to support Hamas’s project in Jordan and Palestine; rather, they only differ at times on the details. The Brotherhood members of Jordanian origin and the hawks who support Hamas’s project and work for its support apparatuses do so because they are attracted to its religious and ideological framing. They are also sometimes drawn in as a result of their personal and religious interests converging.

On the other hand, doves of Jordanian origin who are either involved in the Zamzam project, the Group of Elders, or the new Muslim Brotherhood Society engage in religious activity to serve the interests of a national project. They are thus closer to the regime in approach and are more likely to avoid confrontation, preferring to stick to “soft” opposition in pursuit of political reform, within the framework of their ideological convictions.

Regarding the coup in Egypt, it has become evident that the coup has failed to provide for the needs of the Egyptian people. The gradual decline in enthusiasm among the Egyptian public toward the coup and the resulting regime has provided an impetus for Islamic movements to once again embark upon a project of reform and proffer political Islam as society’s next alternative.

Furthermore, in addition to the Egyptian experience, both the Libyan experience (with General Khalifa Haftar) and the Yemeni experience (with former president Ali Abdullah Saleh) have failed to provide a viable alternative to political Islam.

The societal consciousness of the Arab people is gradually moving toward a greater level of mistrust in the military. This reality will surely be exploited in the future by Islamic movements running on platforms of peaceful and gradual reform and will aid their being accepted by the people. This is precisely what is encouraging a few trends in Jordan at the moment, such as

- Zamzam’s establishment of an affiliated political party, The National Congress Party, and the establishment of the Elders’ party, the Partnership and Rescue Party, as I mentioned earlier;

- A change within even the parent Muslim Brotherhood movement toward greater openness, coalition-building with a more national orientation, and a focus on “soft” opposition; and

- A decline in support for the Muslim Brotherhood Society, due to its inability to formulate a new and inspiring political project. It is currently lost, having failed to distinguish itself from various other emerging ideas and political parties.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).