Every day, Willie McShan climbs into a beat-up Chevy van in the parking lot at the Greater Praise Church of God in Christ in Milwaukee and gets a free ride to his job at an auto parts plant in Sheboygan County, Wisconsin. This is a one-church solution to the problem of a lack of jobs in the inner city, and a blessing for the companies facing labor shortages out in Sheboygan.

The Milwaukee metropolitan area has a decent enough economy, ranking 47th out of 100 for ‘prosperity’ and 68th for growth over the last five years, according to the latest Brookings Metro Monitor. But like many other U.S. cities, the problem is that the fruits of this growth are not shared widely, especially across barriers of race and geography. Segregation means that affluent neighborhoods (Milwaukee sees its second branch of Whole Foods opening next week) co-exist with deeply poor city tracts.

The issue facing Milwaukee and other cities is the lack of connection between the areas of greatest need and the areas of greatest growth.

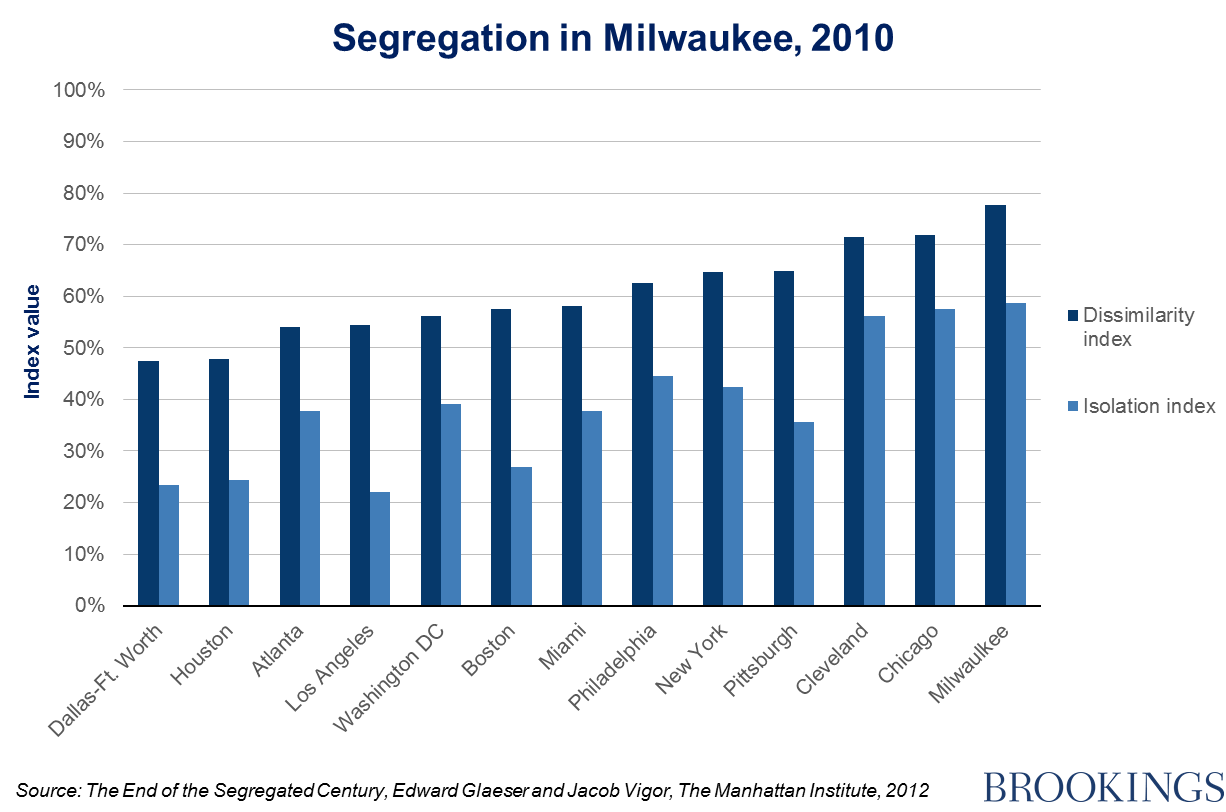

Milwaukee: Leader in segregation

Milwaukee is the most segregated metro area in the United States. (Note that in our earlier blog on Chicago we only listed the biggest ten.) In 260 of Milwaukee’s 296 census tracts, the members of one demographic group account for more than 60 percent of the tract’s population. Milwaukee has the highest dissimilarity index—0.78—of any major metropolitan area, according to research by Edward Glaeser and Jacob Vigor. That means 78 percent of black residents or 78 percent of other residents would have to move for Milwaukee’s neighborhoods to be demographically balanced. A similar picture emerges if we apply a slightly different measure, the “isolation index”:

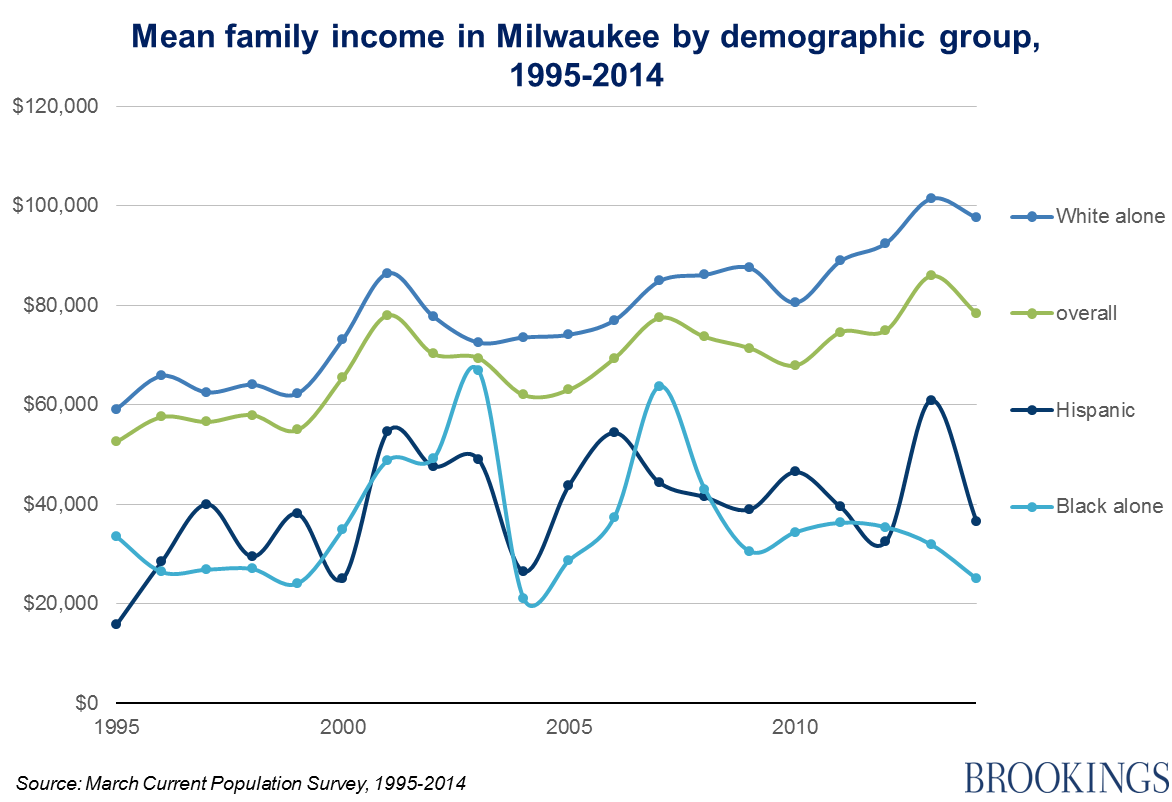

Race gaps in family income

The dangers of relying on metro-wide averages can be seen in an analysis of income by race. Mean family incomes for black and Hispanic Milwaukeeans have consistently trailed white incomes. If anything, the gap is widening:

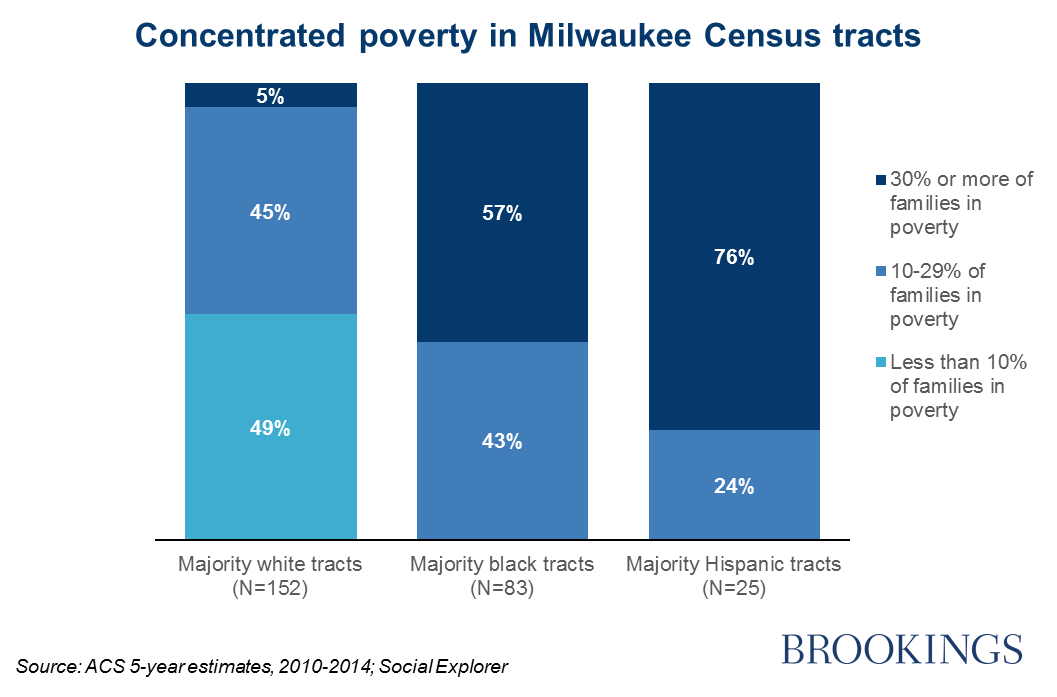

Concentrated poverty: Not for whites

The combination of income gaps by race and residential segregation means a stark difference in the nature of black, white, and Hispanic census tracts (defined as those where more than 60 percent of the population is from the dominant group). Just 5 percent of the mostly white tracts have more than 30 percent of families in poverty, compared to 57 percent of the mostly black tracts, and 76 percent of the mostly Hispanic ones:

Now welfare reform requires desegregation

Wisconsin is seen by many as the cradle of the welfare reform movement of the 1990s; even then, Milwaukee seemed to benefit less than other parts of the state. Two decades on, it is clear that creating jobs and incentives is not enough. We also need to address the barriers to opportunity generated by deep, stubborn segregation. The stakes are economic and personal. As McShan told Rick Romell, a reporter for the Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel, the bus to work has changed his life. “I’m a part of something. I just feel like I can wake up tomorrow, and it’ll be there.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Milwaukee, segregation, and the echo of welfare reform

February 17, 2016