Marcela Escobari is a senior fellow at Brookings. She served in the White House National Security Council as special assistant to the president and coordinator for the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection. In this role, she led efforts to advance a collaborative, regional response to the displacement of over 10 million people across Latin America and the Caribbean. She was confirmed twice by the U.S. Senate as assistant administrator for USAID’s Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean, under Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden. Alex Brockwehl is a visiting researcher at Brookings and previously served as director for migration cooperation at the National Security Council.

Overview and key lessons

Few policy areas have seen less durable progress over the last thirty years than migration. Repeated attempts to negotiate a grand bargain on immigration have failed, and the issue is widely considered a “third rail” of American politics. The issue has only festered, becoming a top concern for voters over the last three U.S. presidential election cycles. We see today how profound and far-reaching the consequences of current migration policy can be: Even amid multiple global conflicts and a trade war, the Trump administration’s defiance of court orders and deployment of National Guard troops as part of its mass deportation policy are so far providing the most significant test of the rule of law.

While the Trump administration has fulfilled its campaign promise to bring border encounters down to historic lows—accelerating a downward trend that began in the closing months of the Biden administration—it has done so by presenting a false choice to the American people, suggesting we cannot continue to be a land of opportunity and also have a secure border.1 The administration has cast most immigrants as “criminals” or “terrorists”, despite clear evidence to the contrary.2 And it has weaponized immigration enforcement to create a culture of fear, not only among non-citizens but even by targeting those who might come to immigrants’ defense. With a few notable exceptions, the administration seems intent on cutting off most legal migration options, including for those who could fill labor gaps in the U.S. and those fleeing persecution, conflicts, or natural disasters.3 Far from learning lessons from the family separation policy, which provoked widespread outrage during President Trump’s first term, his administration seems intent on going further and faster this time around.

If recent history is any indicator, the pendulum of public opinion is likely to swing back again (in fact, recent polling suggests opinion is already shifting against the Trump administration’s approach). And when it does, there may be a narrow window of opportunity to tackle the underlying problems that have plagued the U.S. for decades. Seizing that moment will require a better understanding of what does and does not work to devise policies that advance the full range of U.S. interests at stake—economic, moral, and strategic. This paper seeks to draw lessons from the Biden administration’s approach—both its progress and its pitfalls—to help shape a more balanced migration policy.

Even though immigration reform has eluded Congress for decades, better policy is possible. Americans broadly agree on many of the key tenets of a balanced and pragmatic immigration policy, from increasing enforcement resources at the border to providing a pathway to citizenship for migrants already in the U.S. and linking legal migration pathways with labor market needs. Countries like Canada and Australia have developed systems that more directly link immigration to labor market needs. Moreover, with a larger share of the American population aging out of the workforce, and immigrants playing an increasingly vital role in helping drive U.S. economic growth, the need for a balanced and predictable migration policy has only become more urgent.4

What we see today is not success. Success is an orderly and efficient border where asylum claims are adjudicated quickly in accordance with U.S. and international law. It is a system that makes available lawful pathways that serve our various interests as a country while enforcing the rule of law and imposing consequences for those who cross the border irregularly. Under this kind of system, the government has the tools to increase or decrease migration levels in response to labor market needs, global crises or shocks, and communities’ capacity and willingness to absorb and integrate newcomers.

Achieving such a system has been a challenge for every recent administration. But the urgency to do so only grows. This century will bring more global crises and rapid demographic and technological change, and adapting to these changes will require a modern and functional migration policy.

Why look backward as we move forward?

In considering future migration policies, it may be tempting to write off the Biden administration’s record. After all, poll after poll showed migration to be a political vulnerability for both President Joe Biden and then Vice President Kamala Harris in their campaigns against Trump. But the Biden administration confronted a regional migration crisis and implemented a range of new policy responses that ultimately began to show durable results; a close examination of which policies worked and which did not can offer valuable lessons for future policy.

By the final months of the Biden administration, in late 2024, irregular border encounters between official ports of entry had dropped over 80% from their 2023 peak.5 This decline was driven by a range of strategies, but in particular, stepped-up enforcement combined with the availability of newly authorized pathways for over 1.7 million people that were rolled out in 2022 and 2023.6 These policies not only eased pressure at the border but also enabled migrants to fill critical labor shortages, providing a buffer that helped the country avoid a post-pandemic recession. The Biden administration also leveraged diplomacy and foreign aid to help partner countries absorb and resettle 4.5 million migrants within the region and enhance their own enforcement efforts. This migration diplomacy strategy, which is often overlooked in domestic policy discussions, proved instrumental in reducing migrant flows to the U.S. border and supporting countries in the region that were at the frontlines of the migrant crisis.

Of course, there were significant drawbacks to these policies as well. The rapid arrival of so many migrants strained the resources of major U.S. cities, fueling public frustration and contributing to an anti-immigrant backlash. Moreover, because these new pathways were created by executive action rather than legislation—and in each case were authorized as emergency, temporary measures—they were vulnerable to legal challenges and swiftly reversed by the Trump administration. Since taking office, the Trump administration has taken steps to rescind the status of over 1.3 million immigrants who had been legally living and working in the U.S.7 The move has not only upended lives and sparked court challenges, but it has generated uncertainty and labor shortages for businesses that rely heavily on immigrant labor, particularly in sectors like healthcare, hospitality, construction, and agriculture.

Looking back is not about relitigating the past; it is about identifying the major reforms needed to build a system that not only responds to crises but helps prevent them. Congress has not passed comprehensive immigration reform in over 30 years, but the stakes are too high to give up hope. By offering an inside look at how the Biden administration managed the largest migration displacement in Western Hemisphere history—and the highest number of border encounters since record keeping began in 1925—we hope to inform the next generation of policymakers who are ready to put solutions above politics. Understanding the past is the first step in forging a better way forward.

Lessons

Among the key lessons we highlight from the Biden administration’s response:

1. Enforcement and lawful pathways are not opposing strategies—they are interdependent

Key to slowing migrant flows to the U.S. border was deploying various policy levers simultaneously. Political leaders often talk about the need to sequence policies to earn political space for hard reforms—enforcement first, then relief. But in practice, sustainable reductions in irregular migration required multiple, mutually reinforcing lines of effort at the same time, specifically linking enforcement measures to available lawful pathways. Combining lawful options with clear consequences for unauthorized entry changed migrants’ risk calculus and encouraged the use of legal channels, even if that meant waiting.

2. Emergency parole programs were a necessary and effective, but imperfect, stopgap

Most of the United States’ legal immigration quotas were set decades ago and no longer reflect current labor market needs or the bipartisan priority of attracting and retaining top talent to strengthen U.S. competitiveness. We speak often about immigrants “coming the right way,” but the reality is it has become nearly impossible for most people to do so. In the absence of legislative updates, the administration relied on humanitarian parole to expand authorized entries—most notably through the CHNV program for Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan nationals and the asylum scheduling Customs and Border Protection (CBP) One app.8 These tools allowed migrants to apply from where they were, reducing unlawful crossings and allowing vetted migrants to enter the workforce quickly, contributing to a strong economic recovery.9 Criticism that these efforts represented “open borders” policies often overlooked their deterrent impact on irregular flows and ignored how decades of congressional inaction have led to a severe lack of legal ways for migrants to fill labor gaps. The real lesson is not that these tools failed, but that better, more permanent ones are needed.

3. Regional cooperation was indispensable

The policies of our neighbors affect the U.S. directly. It was regional diplomacy—securing cooperation from countries like Mexico and Panama and supporting partners who resettled over 4.5 million migrants—that helped reduce flows. U.S. foreign assistance played a catalytic role, but the bulk of resources came from host countries. The Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection provided a framework for hemispheric cooperation, accelerating coordination and the sharing of data and best practices among many Latin American countries responding to record levels of displacement.10 This regional burden-sharing model proved far more effective—and far less costly—than unilateral deterrence at our border.11

4. Cities bore the brunt of the crisis and needed faster federal support

The upfront costs of managing migrant flows are felt almost exclusively by states and cities, even though the long-term fiscal benefits are more broadly shared. To make this concrete, the Congressional Budget Office projects that increased immigration over the last five years will contribute over $90 billion in annual federal revenue. Yet, cities faced acute challenges: shelter overcrowding, strained public services, and housing shortages. Because there is no federal government agency in charge of surging support when needed, the few transfers that happened under the Biden administration went through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), an agency focused on natural disasters and already cash strapped. Aid was eventually approved by Congress specifically to deal with migration, but it was delivered in spurts and with constraints on who could access it. Invoking an emergency declaration earlier, while politically tenuous at the time, would have unlocked some additional local and federal capabilities and provided local authorities with the political cover to respond. By the time the administration took steps to expedite migrants’ insertion into labor markets, the damage had already been done. The lessons point to ensuring more and faster transfers, accelerating work permits for migrants, improving coordination between cities and the federal government, and promoting more geographic dispersion to facilitate the integration of new migrants into communities best able to absorb them. While we tend to think of immigration as primarily a federal government authority, the Biden administration learned the hard way that failing to get the local level response right comes at a cost.

5. Private sponsorship is a scalable model for the future

The global refugee system is outdated and overwhelmed. Fixing it will require a range of solutions, from expanding labor pathways to helping countries support displaced people closer to home. In responding to different international crises, the Biden administration turned to private sponsorship as a necessary complement to existing refugee resettlement programs. Through programs like Uniting for Ukraine (U4U), the process for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV) and Welcome Corps for refugees, Americans across all 50 states helped resettle more than 780,000 newcomers. These private sponsorship programs, some scaled through the use of humanitarian parole to respond to immediate crises, have proven to be an efficient and scalable way to resettle and integrate migrants and refugees. This bottom-up approach was not only cost-effective but also tapped into widely held American values of generosity and opportunity.

Ultimately, crisis was the catalyst for innovation. Faced with historic migration surges and an outdated system, Biden administration officials were forced to take risks, iterate quickly, and adopt policies that might have been politically or bureaucratically impossible in ordinary times. Not all efforts succeeded. But the failures were as instructive as the successes. Where the administration struggled most—mitigating the strain on cities, aligning enforcement and lawful pathways earlier, and communicating policies effectively to the American people—are areas where the lessons can be especially valuable in shaping future reform efforts.

In the pages that follow, we offer a detailed, insider account of the strategies the administration deployed to respond to record migration flows. We explore what worked, what did not, and what future administrations—regardless of party—can learn from this moment.

Understanding the surge

Displacement in the Western HemisphereWhen the Biden administration took office, the Western Hemisphere was in the midst of the largest displacement of people in its history. With over 10 million people displaced, this would become the defining driver of migration to the southwestern border of the U.S.

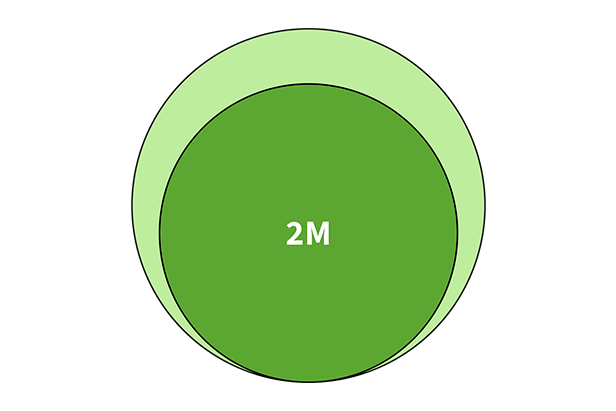

While migration surges are not new, the scope and scale of recent flows were unprecedented (Figure 1). Past spikes—such as Mexican migration in the 1950s, the Cuban raft exodus in 1994, and the Central American child migrant crisis of 2014—pale in comparison to the sustained volume of arrivals beginning around 2017 and peaking in 2022 and 2023 when U.S. border encounters exceeded two million annually.

To understand this spike, we must look beyond the U.S. border. Much of the new flows were driven by the collapse of Venezuela. Over 7.7 million people—roughly a quarter of the country’s population—fled repression and economic ruin under the Maduro regime. At the same time, Latin America faced the deepest COVID-19 recession of any region globally, costing an average of 7% of GDP, and pushing more than 20 million people into poverty. During this time, criminal networks also became more prevalent in the human smuggling business and their tactics more sophisticated—for instance, recognizing the strains on detention capacity, they began coaching migrants to turn themselves in and claim asylum.

As COVID-19 travel restrictions subsided, the U.S. experienced one of the fastest economic recoveries in the world, with job openings far outpacing available workers. By July 2022, there were two open jobs for every unemployed person, up from 0.7 in January 2021. Consistent with the trend over the last 25 years—which shows a strong correlation between job availability in the U.S. and border crossings—increased labor demand clearly drew migrants north.

The result was not only an increase in migration, but also a dramatic shift in its composition. Historically, the vast majority of migrants encountered at the U.S. border came from Mexico and Central America. In fiscal year 2014, just 7% of border encounters were from outside Mexico and Central America; but by 2023, that number had climbed to 51%, reflecting growing numbers of migrants arriving from South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia.

No route better illustrates this transformation than the Darién Gap—a once impassable stretch of jungle between Colombia and Panama that by 2023 had become a major corridor for over half a million migrants, most of them Venezuelan. The growing number of migrants from faraway places made returning them more complex, as doing so required fresh diplomatic efforts, costly flights, and in some cases, negotiations with recalcitrant governments often unwilling to take their citizens back.

The border policy landscape only added to the pressure.12 Title 42, invoked during the pandemic, allowed quick expulsions to Mexico without formal processing (Figure. 2)—reducing detention strain but also removing penalties for repeat crossings. Recidivism spiked: Repeat encounters soared from 7% in 2019 to 27% in 2021, with rates reaching 49% for Mexican and northern Central American migrants in May 2022. After years of declining border encounters, Mexican migration surged under Title 42. Though litigation delayed its termination, the administration was also slow to prepare for a return to using Title 8—a more rigorous process that, while slower, imposes real consequences and has proven more effective at curbing repeat entries.

Figure 2. Nationality affects enforcement actions at the US southwest border

Monthly encounters by processing outcome at the US southwest border, October 2013-November 2024

Critics of the Biden administration often point to its early policy shifts—rolling back the Muslim ban, halting border wall construction, and announcing a deportation moratorium (for internal, not border, enforcement)—as magnets for increased migration.13 It is true that President Biden ran on a campaign of change from his predecessor and promised a more humane approach to migration. But while this rhetorical shift likely had an impact on flows to the U.S., there were deeper structural drivers at play: economic collapse, regional instability, and pent-up labor demand in the U.S.

In the next section, we turn to the Biden administration’s policy response—examining its effectiveness to better identify the core components of a pragmatic migration policy.

The power of policy mix

Enforcement and lawful pathways to change migrants’ risk calculusThe prevailing narratives about the Biden administration’s immigration policy either cast all of its actions as overly permissive or criticize its late-stage enforcement measures as “too little too late.” These narratives miss a key insight; the administration’s most effective actions stemmed from combining lawful pathways with targeted enforcement to influence migrant decision making.14

From 2021 onward, the administration introduced a series of policy changes designed to both deter irregular migration and offer viable alternatives. While some critics accused the White House of adopting an “open borders” stance, many of its parole programs were explicitly tied to enforcement measures. Migrants who failed to utilize these legal avenues often faced heightened consequences, including rapid removal or ineligibility for asylum.

Empirical evidence suggests that expanding lawful pathways can help reduce irregular migration. For instance, in a 2024 paper, economist Michael Clemens finds that a 10% increase in lawful border crossings leads to a 3% decrease in irregular crossings within 10 months. In other words, expanding access to lawful pathways is a “partial but substantial deterrent” which, when combined with increased enforcement measures, can impact migrants’ risk calculus, nudging them toward legal options instead of more dangerous and unauthorized routes. However, this substitution effect is not immediate—it takes time, must be implemented at scale, and paired with credible enforcement.

This dynamic was evident during the Biden administration. After peaking in late 2023, border encounters began to decline. Mexico’s increased enforcement was a key contributor. But the U.S. also layered in new lawful alternatives to enter the country and tightened asylum eligibility if daily encounters exceeded 2,500. By the end of 2024, this balanced approach had reshaped border dynamics. Total monthly encounters at the Southwest Border fell by two thirds—from a high of 300,000 to fewer than 100,000—and authorized encounters at ports of entry via programs like CHNV and CBP One exceeded unauthorized encounters in between ports of entry (Figure 3). These programs’ pre-vetted applicants reduced pressure on border patrol, decongested detention facilities, and freed up processing resources to remove those without valid asylum claims faster—ultimately destressing and streamlining the system and allowing it to function more effectively.

BOX 1

The border as a water system and the dual goals of increasing border capacity and reducing migrant flows

The analogy often evoked for migration policy is to think of migration as water and our border as a dam designed to manage the flows. Water ebbs and flows with global events—economic downturns, political instability, natural disasters, and labor demand. Migration is a force that, when well-managed, can be harnessed to support growth, resilience, and renewal. A well-designed dam does not aim to stop water entirely. It manages flow—protecting downstream communities while ensuring water goes where it is needed most. The same is true at the border. The goal is not zero migration. The goal is manageable, legal, and beneficial migration that flows through structured, intentional channels.

But even a well-built dam has a limit—it has carrying capacity, the maximum flow the system can process without spilling over. That is what the U.S. border has too. At the border, that capacity depends on a complex web of operational resources: the number of CBP and ICE beds and holding capacity, processing infrastructure of asylum officers and immigration officers, and transportation and removal logistics. When encounters exceed that capacity, the system is forced to release pressure—often by issuing Notices to Appear (NTAs) with court dates years in the future and transferring migrants to already strained cities (Figure 5).

The story of the border during the Biden administration is one of shifting pressure and expanding capacity. Its policies focused on bringing flows below the system’s carrying capacity, while at the same time gradually increasing processing capacity. By the end of 2024, the system could process over 2,500 individuals per day—a meaningful increase from years prior (Figure 4). As processing capacity increased, fewer migrants were released into the U.S. while they awaited hearings. The administration showed that establishing control does not require zeroing out migration altogether but rather bringing flows below the border’s carrying capacity.

The trajectory of enforcement and lawful pathways policies

It is important to remember that the Biden administration’s first actions to step up border enforcement occurred in 2021, not 2024. Beginning in 2021, officials advanced reforms to tighten asylum eligibility and expedite case adjudication to close the asylum loophole that was filtering so many people into a heavily backlogged system. A key move was allowing asylum officers—not just immigration judges—to adjudicate claims, helping to reduce the backlog and mitigate a perverse incentive: migrants turning themselves in to authorities to secure court dates years into the future.

As global crises emerged, the administration responded with tailored tools. When Ukrainian nationals surged to the border after Russia’s invasion in early 2022—with as many as 1,000 Ukrainians showing up each day in Tijuana—the administration launched Uniting for Ukraine (U4U), a private sponsorship parole program. The administration mobilized a rapid, whole-of-government effort, with clear messaging to discourage irregular entry. Legal arrivals displaced irregular crossings almost immediately (Figure 6), and the private sponsorship component of the program served as a natural constraint on program size.15

This model was scaled with CHNV. Launched in October 2022 for Venezuelans, and then expanded in January 2023, it allowed up to 30,000 vetted migrants per month from four countries to enter legally if they applied from abroad (rather than show up at the U.S. border) and had U.S.-based sponsors. At the same time, those from the same countries who attempted irregular entry were swiftly expelled to Mexico. The program had immediate and eventually enduring effects [see Appendix 1 for details], reducing irregular encounters from these countries dramatically while providing over 530,000 migrants the opportunity to obtain a 2-year work permit and fill labor gaps. The number of lawful pathways made available was far lower than the number of migrants attempting to cross irregularly. Even as the number of parole entries was reduced—from 1,000 per day in June to fewer than 10 per day in October 2024 after the program was paused to address concerns around CHNV sponsor vetting—it did not trigger a shift toward irregular migration. This underscores how the combination of increased enforcement and a lawful pathway worked to shift behavior (Figure 7). And just as importantly, this balanced approach opened the door for increased enforcement cooperation between the U.S. and its neighbors. Specifically, CHNV allowed the U.S. to negotiate with Mexico to receive up to 1,000 returns per day of Venezuelan, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Cuban nationals that did not avail themselves of these new lawful pathways. While implementation was difficult and Mexico received a small number of Venezuelans at the start, this arrangement also encouraged Mexico to increase their own internal enforcement, taking steps to limit travel for migrants further south who were making their way to the U.S. border.

Meanwhile, CBP One, a mobile app launched in early 2023, allowed 1,500 migrants a day to schedule asylum appointments in advance. During the period that CBP One was in effect from January 2023 to January 2025, nearly 1 million migrants scheduled appointments at ports of entry. It allowed migrants to be pre-screened, giving law enforcement officials time to assess potential security threats and collect information about those entering the U.S. While the app was criticized by some human rights advocates, who alleged it unduly restricted asylum access, its effectiveness in controlling border arrivals is undeniable.

Further steps, such as the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways Rule and the Securing the Border Rule, added teeth to these efforts by denying asylum eligibility to those who bypassed legal channels. The Securing the Border Rule, implemented in June 2024, suspended most asylum cases when encounters exceeded 2,500 a day, and could only be reinstated after the 14 day average dropped below 1,500 per day. The rule effectively increased the threshold for initial asylum screening from credible fear to requiring a proactive manifestation of fear. The rule was controversial. Officials defended it as a legal way to get border numbers under control, enabling more efficient removal of those lacking valid claims while keeping asylum open to those who truly needed it. But human rights groups and other outside experts assailed the rule as a violation of U.S. and international law. Administration officials also debated this measure extensively, but after Congress did not pass the bipartisan border security bill, the administration enacted the rule, which had the intended effect of further reducing irregular flows to the border. This kind of measure may prove to be vital in future crises, making the establishment of other protection pathways that can be accessed away from the border (as Biden attempted with the Safe Mobility Offices across Latin America) even more important.

Lastly, the administration worked with partner countries to expand repatriation flights and step up their own enforcement actions. By securing agreements with key regional partners like Colombia and Ecuador to increase the number of return flights, the administration was able to more quickly remove those without a legal basis to remain in the U.S., thereby reducing the strain on detention facilities. Mexico’s cooperation in more aggressively going after smuggling and trafficking organizations and limiting the use of buses and trains for migrant smuggling proved crucial to bringing down irregular flows in 2024. The administration also launched a pilot with the government of Panama in mid-2024 to repatriate migrants who entered Panama through the Darién Gap, rather than facilitating their transit northward toward the U.S. The number of migrants transiting through the Darién Gap plummeted as the combination of increased deterrence and lawful pathways started to work.

These steps all sought to change migrants’ risk calculus, incentivizing them to apply for lawful options rather than pursue dangerous irregular journeys to the U.S. The administration’s policy steps were not without detractors, as rights groups called these steps draconian and overly restrictive of asylum access while Republican governors sued to block the lawful pathways programs. But it was precisely this multifaceted approach, combining lawful pathways with credible enforcement, that ultimately reduced irregular migration in a constrained and suboptimal policy context in which Congress chose not to support a bipartisan compromise that would have increased border patrol, detention, and repatriation resources.16

You cannot do it alone

Why migration response must be regionalOne of the clearest lessons from the Biden administration’s experience is that migration management cannot succeed through unilateral action alone. Regional dynamics—economic instability, shifting visa rules, and other countries’ policy posture toward migration—directly shape who arrives at the U.S. border and when. Any sustainable solution requires cooperation across borders.

When Colombia offered 10-year Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to 2.4 million Venezuelans, onward migration slowed. But when it cut off eligibility in January 2021, meaning those who arrived after this date would not be eligible, the U.S. immediately saw more migrants passing through Colombia and continuing north in search of opportunity.

This trend played out repeatedly as other countries’ policies impacted flows to the U.S. border. The policy changes that Chile enacted toward Haitians in 2021, for instance, making it much harder for Haitians already living in Chile to obtain or renew residency permits, led to a wave of migration of Haitians from Chile to the United States, culminating in the Del Rio episode, where the gathering of thousands of Haitian migrants under a bridge led to a local state of emergency, an ugly confrontation with border patrol agents, and the mistreatment of many migrants.

Similarly, after Mexico imposed a transit visa requirement for Venezuelan migrants, targeting those who had been flying into Mexico to travel north to the U.S., migrants found other ways to come up to the southwest border—specifically through the dense jungle in the Darién Gap—and numbers again reached another all-time high (Figure 8).

Because of this interdependence, a more coordinated strategy across partner countries was clearly needed.

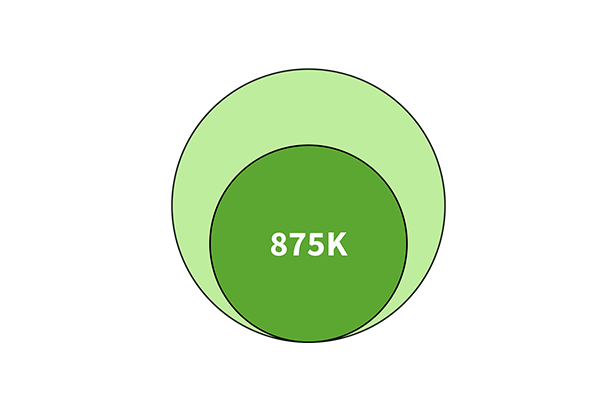

The benefits of regularization and integration: What actually keeps people in place

One approach that worked at scale was the development of a patchwork of policies across the region providing migrants legal status and work authorization. Countries throughout Latin America—in particular Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil—received more than 80% of the Venezuelan exodus. Their integration policies enabled many migrants to access public services, enroll their kids in school, and seek formal-sector jobs. These and other neighboring nations granted legal status to over 4.5 million migrants, also helping reduce onward migration to the United States. These policies effectively absorbed millions of migrants in place—de facto taking them out of the pool of displaced people. UNHCR and Migración Colombia data support the relationship between these policies and reduced onward flows to the U.S., showing that relatively low numbers of those who transit through the Darién Gap have a residency permit in another country.

These policies were not just acts of generosity—they were smart crisis management. Countries like Colombia and Peru were dealing with a migrant crisis almost unprecedented in scale (see Figure 9, which shows how the massive displacement mostly affected Latin American countries). By providing legal status, access to education and health services, and permission to work, regional governments gave displaced people reasons to stay and contribute. The immediate cost was significant: Colombia spent an estimated 0.5% of its GDP on integration efforts in 2019 alone. But over time, these investments are projected to pay off through higher tax revenue, labor market participation, and GDP growth.17

Small checks, big returns: The US’ role in integration success

U.S. foreign assistance—while comparatively modest—was instrumental in making these efforts viable. During the Biden administration, more than $500 million per year in humanitarian and development aid helped countries set up integration programs, establish one-stop migrant support centers, and support innovative initiatives like Brazil’s labor matching system (Operation Welcome) or Peru’s professional credential verification for Venezuelan doctors and nurses.

During the first Trump administration, the U.S. Government had significantly increased humanitarian aid to respond to the Venezuelan migration crisis, reaching close to $1 billion from 2017 to 2020. The Biden administration maintained this commitment, providing humanitarian assistance to help the most vulnerable migrants meet their most basic needs, enabling them to get back on their feet while they figured out life in a new place. U.S. foreign assistance was a drop in the bucket compared to what these countries put toward this challenge, but it was instrumental to these policies’ success. [See Appendix 2 for more detail on the effects of foreign aid].

BOX 2

Snapshot of success: How 4 countries stepped up

South American countries absorbed and integrated displaced Venezuelans who might have otherwise migrated onward to the U.S.

% = share of hosted displaced persons relative to host-country population

Colombia

5.3% of population

Colombia led the way. In 2021, then President Duque announced a new policy to provide 10-year temporary protected status to over 2 million Venezuelan migrants. Since the policy went into effect, migrants with TPS have reported higher levels of household income and consumption, a greater sense of social integration and belonging, and higher rates of enrollment in schools and health services. U.S. foreign assistance played an important supporting role, for instance by funding one-stop-shop integration centers run by the Colombian government that enabled migrants to apply for benefits, enroll their kids in school, or learn about job opportunities. In an era of mass displacement around the globe, Colombia’s effort to welcome and integrate close to 3 million Venezuelans stands out as an example for the world.

Peru

4.9% of population

Peru has also stood out for its important response to Venezuelan migration. Its capital, Lima, has received over 1 million Venezuelan migrants alone. While Peru has confronted some of the most challenging and visible examples of xenophobia against Venezuelans, it has also advanced innovative approaches to verifying professional credentials of migrants, enabling them to overcome barriers and provide the full extent of their skills in new communities. As a result, Venezuelan doctors and nurses served at the front lines of Peru’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Brazil

0.4% of population

Brazil has also been an important leader in welcoming and integrating migrants, pioneering the most innovative labor matching program for migrants in the region. Through Operation Welcome, Brazil has welcomed over 600,000 Venezuelan migrants and matched more than a third of them directly with job opportunities throughout various parts of the country through its interiorization program.

Ecuador

2.6% of population

Ecuador followed closely behind, launching three waves of migrant regularization programs to provide legal status about half of the more than 500,000 Venezuelans living there. Ecuador also provides access to education and health benefits to migrants upon arrival, irrespective of status. The government engaged media around reporting about migrants without baselessly stoking xenophobia.

Note: Total in-country estimates of the forcibly displaced population (asylum seekers, refugees, and others in need of international protection) are sourced from UNHCR using their end-of-year 2024 estimates. The population with temporary residency permits is sourced from country-level data and conversations with local partners.18

The LA Declaration: A regional framework on paper and in practice

In 2022, Biden administration formalized a new regional cooperation framework: The Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection (LA Declaration). Twenty-two countries agreed to shared goals and over two years, endorsing countries gave over 4.5 million migrants legal status, launched 300+ new transit visa policies, and worked together on law enforcement investigations of transnational migrant smuggling groups.

Migration diplomacy under the Biden administration was a two-way street, with the U.S. encouraging countries to step up and do more and also coming to the table with foreign assistance resources and high-level political cover to help partner governments tackle their migration challenges. Migration cooperation became a top foreign policy priority for the United States. Even as wars raged in Ukraine and Gaza, Secretary of State Antony Blinken attended four Los Angeles Declaration Ministerial meetings in three different countries, demonstrating the U.S. Government’s commitment to high-level migration diplomacy.

A regional chain reaction

As countries stepped up, others followed. In one remarkable sign of the buy-in to this shared framework, countries like Argentina and Uruguay launched new regularization efforts in 2024—even as they anticipated potential outflows from Venezuela following what were expected to be unfree and unfair presidential elections in July. In total, eleven countries in the region have implemented generous policies to integrate Venezuelans and other migrants. What started as a crisis response started to look like a regional compact.

This multilateral approach enabled countries to coordinate on measures like transit visa policies that can become a form of whack-a-mole if countries undertake isolated actions. For instance, when Chinese nationals had started taking advantage of Ecuador’s visa-free policy, the government of Ecuador took important action, in coordination with the U.S. and other regional partners, to close this loophole. The number of Chinese nationals transiting the Darién Gap quickly plummeted by nearly 90%.

As each country stepped up, it motivated others to also adopt a bold and welcoming approach to migration, even if there could be short-term political costs.

From burden to benefit: The opportunity of labor migration

By the end of Biden’s term, some countries were starting to treat migration not just as a problem, but as a resource. Efforts to expand labor pathways were central to this mentality shift. U.S. partnership with Northern Central American countries tripled the number of H-2 visas issued to the region between 2021 and 2024, surpassing 30,000. This new model relied on local government buy-in, rather than private recruiters, to help match labor migrants with U.S.-based employers.19 Other countries with growing rates of outmigration, like Colombia and Ecuador, sought U.S. partnership to help their citizens access H-2 visas as well. These efforts were informed by research showing that these kinds of pathways serve as substitutes for irregular migration.

It became increasingly clear that it was not just the U.S. or Canada that could benefit from well-managed labor migration. Countries like Mexico with aging populations or Guyana and Suriname with booming new industries all have labor needs that well-managed migration could help fill. It was with this in mind that Secretary Blinken launched the Labor Neighbors initiative in 2024, with the goal of creating a regional and ultimately global marketplace for talent to match labor supply to demand across the hemisphere and beyond. As International Organization for Migration (IOM) Director General Amy Pope and others have written, expanding labor pathways will be increasingly critical in an era of growing displacement. The benefits of labor migration to growth are well documented across the globe.

With the Trump administration walking away from the declaration and so far disengaging from most multilateral fora altogether, it is too early to tell what the impacts will be. The approach of applying pressure on key countries has so far led to some countries accepting foreign nationals, albeit with significant legal hurdles and logistical and optical challenges for key partners. The Biden administration found that countries needed to see that the benefits of coordinated action pay off economically and politically inside their own countries. While pressure tactics may yield temporary cooperation, they are unlikely to build the trust and shared investment required to manage future waves of displacement effectively. And it is worth questioning whether this approach focused solely on deterrence will merely delay, rather than prevent altogether, irregular migration.

The lesson is clear: Strong partnerships, not just strong-arm, unilateral tactics, are the foundation of a sustainable, modern migration policy. Regional integration policies—not just enforcement—are the invisible infrastructure that prevented millions from ever reaching the U.S. border.

The refugee versus migrant conundrum

A system built for a different eraOne of the most persistent challenges the Biden administration confronted was the mismatch between modern migration realities and the outdated legal frameworks meant to manage them. The U.S. asylum system was designed in the aftermath of World War II to protect individuals fleeing political persecution. Today, that narrow definition often fails to capture the complex reasons people leave their countries—economic collapse, failed states, climate disasters, or generalized violence. Yet in the absence of alternative lawful pathways, more and more migrants turn to asylum as their only viable option for entry.

This dynamic creates two critical problems. First, it overwhelms the system. Asylum officers and immigration courts are inundated with applications, many of which—while reflecting genuine hardship—do not meet the strict legal threshold for protection. Second, it distorts migrant behavior, incentivizing individuals with primarily economic motivations to claim asylum simply to gain a foothold in the United States.

Countries in Latin America responded to these realities with a more flexible model. Colombia’s approach stands out: Rather than rely on individualized adjudications, it offered a broad-based, temporary protected status to 2.4 million Venezuelans. This streamlined approach avoided years-long backlogs and allowed displaced people to work, access services, and begin integrating almost immediately. Ten other countries in the region adopted similar strategies, bypassing the limits of formal asylum systems to manage large-scale displacement more pragmatically.

The U.S., by contrast, remained tethered to a rigid legal architecture—though the Biden administration took steps to evolve it. Key reforms included empowering asylum officers to adjudicate certain claims more quickly and creating the Circumvention of Lawful Pathways rule and Securing the Border final rule to redirect migrants to legal options before they reach the border.

The administration also launched the Safe Mobility Initiative, which established triage centers in Colombia, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Guatemala where migrants could access information about various lawful pathway options, and if they chose, initiate their application process for refugee resettlement. Though small in scale—resettling around 30,000 people—the initiative represented a promising model: process migration upstream, expand lawful options, and reduce irregular flows. This innovation could undoubtedly be broadened in a future administration to enable migrants to apply for labor pathways to the U.S. and other countries, and pursue other lawful pathway options as well, with the goal of reviewing and adjudicating their cases elsewhere to reduce strain on limited border resources.

Lastly, the administration pioneered a private sponsorship model, leveraging the generosity and philanthropy of American volunteers to help settle displaced people more efficiently than through the refugee resettlement program. Through programs like U4U, CHNV, and Welcome Corps for refugees, Americans helped resettle more than 780,000 newcomers. These efforts did not replace the refugee resettlement program, which grew under the Biden administration to 100,000 refugees resettled in fiscal year 2024, compared to just 11,400 admissions in the last year of the Trump administration. But these private sponsorship initiatives enabled a large number of migrants to put down roots and integrate into communities in a way that would not have been possible through formal refugee resettlement.

This emerging framework reflects a critical insight: Not all displaced people are refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention, but many still deserve protection or opportunity. Expanding alternative pathways—whether for work, safety, or family reunification—is essential to reduce pressure on the asylum system and build a more humane and functional model for the 21st century.

When the border moves inland

Cities on the front linesWhile national leaders shape immigration policy, it is cities that absorb its most immediate consequences. During the Biden administration, a surge of arrivals—many entering legally through new pathways—placed immense pressure on urban systems unprepared for their rapid integration.20

Historically, federal and state governments set immigration policy, while local governments were largely reactive: managing shelters, school enrollments, public health, and housing. But by 2023 and 2024, that equation had flipped. Cities like New York, Chicago, and Denver found themselves on the front lines, not just responding to federal policy but demanding changes to it.

Many of the new arrivals were legally admitted but lacked immediate access to work authorization. They also generally had fewer family networks than traditional undocumented immigrants, meaning that they were less likely to have support and help finding work. As a result, they became dependent on city-funded shelters and support systems at a time when many cities were facing housing and cost-of-living crises. Municipal leaders, even those in immigrant-friendly jurisdictions, began calling for faster federal action—not only to authorize employment more quickly, but to provide emergency funding to cover growing costs. By the summer of 2023, there was a growing chorus from many mayors and governors urging the federal government to do more both in terms of resources and policy changes that would facilitate their integration.

The federal government’s response was inconsistent and slow. The lack of meaningful coordination and communication from federal authorities exacerbated the challenge for cities that were dealing with so many arrivals. And the failure to declare the crisis an emergency not only kept cities from unlocking further resources but deprived local leaders of political cover to more effectively manage the situation. While over $1.6 billion was eventually made available through FEMA’s Shelter and Services Program, much of it arrived late, was restricted in use, and failed to keep pace with the scale of need. In the interim, cities were forced to shift funds from other essential services, leading to political backlash and a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment. The administration eventually moved to expand Temporary Protected Status to nearly 500,000 Venezuelan migrants in 2023, increase eligibility for other nationalities, and expedite the issuance of work permits for those eligible. These policy steps enabled migrants to get on their feet more quickly and get out of government shelters. But the damage in terms of public opinion may have already been done.

The lack of a coordinated response reinforced how cities bear uneven levels of responsibility when addressing a large inflow of migrants. Migrants flocked to places like New York and Chicago, but at the same time that these major cities were being overwhelmed, other cities had unmet labor needs. Policies like community visas could entice migrants to go where the opportunities are. Under one such proposal, communities could apply to the federal government to become destinations for migrants that have certain skills to fill local labor gaps, thereby generating greater dispersion of migrants and more precise matching between demand for labor and migrants with the relevant skills.

While U.S. cities experienced this migrant surge differently from cities in Latin America, there could be value in looking at how other cities in the region dealt with large numbers of Venezuelan migrants. In Brazil, the federal government was proactive in preempting the likelihood that migrants would flock to major cities, launching an interiorization initiative to match migrants who arrived in Brazil with job opportunities in cities and towns throughout the country. In Colombia, the government gave cities a key integration tool with its national TPS policy. And the cities that were bold in attempting to quickly integrate migrants were those that benefited the most economically and seemed to experience less blowback.

BOX 3

Comparative perspective: Bogota’s response to migrant flows

In Bogota, the mayor’s office assembled a team to identify and unlock the key obstacles to migrants’ access to vital government services and integration into the labor market. With U.S. government support, they set up one-stop shops for migrants where they could register in the health system, enroll their kids in school, and get information about job opportunities. They also provided resources to support migrant entrepreneurs and incentivize the creation of new businesses that could hire Venezuelans and Colombians alike. The results were impressive, as migrants created over 9,000 new businesses and generated 188,000 new jobs in the three-year period from 2019-2022 in which Bogota received over 600,000 Venezuelan migrants (nearly 8% of the city’s population). Other cities like Barranquilla took a similarly bold approach. The Barranquilla mayor’s office built partnerships with over 200 local employers with specialized staff working to understand company needs and linking migrants to job opportunities, providing them subsidized skills training as needed.

Despite a slow start, the Biden administration ultimately made some progress—for instance, announcing steps in September 2023 to speed up work authorization processing times and extending the length of automatic renewals—but systemic reform remains unfinished. Necessary steps like shortening the six-month period that asylum seekers must wait to receive their work authorization would require an act of Congress. A future policy must account for the impact that changes to lawful pathways and enforcement measures can have at the city and state level from the very beginning and frontload resources and coordination capacity to minimize disruptions for local communities and speed up labor market insertion and integration processes.

Communication and narrative

The bully pulpit mattersWhatever one makes of the Biden administration’s record on immigration policy, there is little debate that it lost the messaging war—especially among moderate or persuadable observers. Even as irregular border encounters fell sharply in the final year of the administration and diplomatic wins mounted, public perception remained largely frozen. Poll after poll showed immigration approval ratings stuck near historic lows, unmoved by substantive progress.

Here as well, there are lessons. First, perceptions are often cemented early. The Biden administration’s experience likely speaks to the importance of establishing a balanced policy from day one, recognizing that public perception may be hard to shift later. Despite ultimately advancing a balanced and multifaceted policy, the administration’s early tone—emphasizing compassion and undoing Trump era restrictions—set the frame. In a U.S. media environment laser focused on enforcement and border visuals, this frame stuck. Even a pivot to tougher rules could not dislodge the “soft on immigration” label. Explaining the interplay between lawful pathways, enforcement, and regional coordination earlier and more forcefully, and continuing to explain in the clearest possible terms what the administration was doing, was a gamble worth trying. Instead, the administration largely played defense, allowing media outlets and opposing politicians to define the narrative.

Second, the problem is bigger than optics. Immigration has become a proxy for a deeper public distrust in government competence. Americans do not just fear porous borders—they doubt any administration can manage migration effectively. That’s the political baseline any future administration must confront.

And yet, other countries show that the politics do not always play out this way. In Colombia, former President Ivan Duque’s bold response to the Venezuelan migrant crisis became a defining achievement, and one that President Petro continued and expanded. In Brazil, Operation Welcome enjoyed bipartisan continuity—from Bolsonaro to Lula, with minimal fanfare and without significant political cost—a rare area of commonality between two leaders with sharply divergent governing agendas. A recent Inter-American Development Bank study found that only 10% of migration-related media in Latin America is alarmist compared to the dominant crisis narrative in U.S. coverage. Canada, long a champion of skills-based immigration, has maintained broad public support—at least until very recently—by aligning migration policy with labor market needs and national values.

Future leaders will need to do more than fix policy. Those in favor of more pragmatic policies will have to preempt and substantively counter the belief that migrants inherently threaten public safety or burden communities. This requires more than data—it requires reframing, avoiding extremes, and being clear about the trade-offs of every policy. The choice between legal migration and a secure border is a false one, and a future administration must make this case aggressively if it wants to create a political constituency for a moderate, pragmatic approach to migration.

Recommendations

The prevailing narratives about the Biden administration’s migration policies tend to fall into two camps: that any progress made was too little, too late—or that the administration failed because it was too permissive. Both overlook the complexity of what actually transpired—and the real-time innovation required to manage the largest displacement crisis in the Western Hemisphere’s history.

A sober look at the Biden administration’s approach on migration reveals important lessons. The administration stood up lawful pathways at scale, forged unprecedented regional cooperation, and developed a new generation of policy tools. But it faltered in responding quickly to the needs of frontline cities. Its largely defensive messaging allowed others to define the narrative. And it struggled to deliver a compelling public case for the benefits of its approach.

Still, the lessons are clear: Better tools. More flexible lawful pathways. Faster funding for cities. Clearer messaging. These are the building blocks not just for crisis response, but for a functional, forward-looking immigration system that reflects American values and interests.

Policy recommendations for future administrations and Congress

- Build a demand-driven, flexible legal labor migration system. Congress should replace outdated visa caps with a modern, demand-driven system that better matches U.S. labor needs. Current limits—such as the 65,000 H1-B cap (set in 1990 and modestly raised in 2005) and the 66,000 H-2B cap—are disconnected from today’s economic realities. The solution is likely not to impose a new arbitrary cap, but for Congress to create a more flexible system for both high-skilled and lesser-skilled that would accommodate permanent and temporary roles, including non-seasonal, long-term employment and allow regional or place-based visas that align migrants’ skills with local labor needs.21

There have been signs of bipartisan support in Congress for revisiting these caps or at least modifying how they are applied to create more flexibility for employers. For instance, in the current appropriations cycle, House Appropriations members unanimously approved a proposal to not count return workers under the H-2B program toward the annual cap, enabling employers to rehire the workers they need. Another bipartisan proposal would enable STEM graduates with advanced degrees from U.S. universities to seek employment and receive legal permanent residence in the U.S., without it counting against high-skilled visa caps. These processes should be demand driven and less bureaucratic, while retaining protections for U.S. workers to ensure ethical recruitment and equal pay. An independent commission could assess labor market trends and recommend visa adjustments annually. Rather than imposing arbitrary limits that hinder employment and growth, these caps should function as an economic accordion, expanding in times of workforce shortages but also decreasing when jobs are more scarce.22

- Put diplomacy at the center of migration policy. On challenge after challenge, the Biden administration found that the role of regional and global partners was essential for finding durable solutions. Regional burden-sharing, coordinated transit policies, and harmonized integration efforts proved critical. While the Trump administration has so far compelled short-term cooperation from key partners, long-term success is likely to require deep, sustained diplomatic engagement. Multilateralism in migration is not idealism—it is a necessity.

- Use foreign aid as a strategic multiplier. During the Biden administration, U.S. foreign assistance helped an unprecedented number of migrants settle within Latin America. Aid does not just stabilize populations—it builds policy momentum. The first Trump administration had understood this as it also provided increased assistance to address the Venezuela migrant crisis. Yet the current retreat from USAID and global assistance undermines U.S. leverage and trust. This approach has taken away one of the key tools the U.S. has to support partner countries in making life better for the millions of people displaced in the region and reducing the likelihood they will be displaced again. No future administration will be able to undo the harm these actions have inflicted on America’s global standing or trust among our partners. But a future administration should try to leverage foreign aid, even in a leaner form, to advance a balanced migration policy that serves U.S. interests and reflects U.S. values.

- Supercharge labor matching efforts. The misuse of the asylum process, as a way to enter the labor force, is not a U.S. phenomenon, but a global one. Both rich and developing country economies have significant unmet labor market needs, yet the systems to channel migrants with the right skills into the appropriate roles are either nonexistent or outdated and do not tap into already-displaced populations in search of opportunity. There is a huge opportunity for the current administration or a future one to help build an infrastructure across the Western Hemisphere and beyond to help countries match talent with labor needs. Creating such a system would not need to be resource-intensive, rather, it would just require a concerted diplomatic push and harmonization of skills taxonomy and visa regimes. Helping other countries build out their own lawful pathways could ultimately reduce irregular flows to the U.S. while improving life for millions of displaced people and helping partner countries meet their labor market needs and grow their economies.

- Improve federal coordination with cities. The administration’s slow response meant cities were left dealing with the consequences of a huge influx of immigrants, unable to integrate them quickly and move them from being a strain on public resources to contributors to the local economy. Any future expansion of lawful pathways must be paired with rapid-response funding and work authorization reforms. But even absent a future crisis, the Biden administration saw firsthand how, in the future, the federal government must be better coordinated with cities and be able to provide more flexible funding based on needs. Moreover, future administrations should be more proactive in working with cities to incentivize migrants to go where communities and labor markets can best integrate them. One positive result of the last few years is that cities have created valuable technical networks to coordinate responses and share best practices—these should continue and be strengthened going forward.

- Create paths to legal status for long-term migrants already in the U.S. Officials need to bust the myth that creating paths to legal status is unpopular or has a pull effect. Most Americans support it. The Biden administration’s “Keeping Families Together” executive order, which would provide legal status to over 500,000 undocumented spouses—sparked virtually no backlash. Research confirms legalization does not create a “pull factor.”23 It is time to unburden cities and dedicate law enforcement resources to real threats, not separating long-settled families.

- Go on offense with communications. Over the course of the Biden administration, as immigration became largely a defensive issue, there was a growing reticence to speak about an affirmative policy agenda. In some circles, the unspoken mantra was that a day without talking about immigration was a good day. But this reluctance allowed critics to fill the vacuum. Future leaders must shift from a defensive crouch to an assertive case for a balanced approach. Explain the policy. Defend the logic. Trust the public. The opposition will always weaponize fear. The only antidote is clarity and courage.

Despite the Trump administration’s actions thus far, a window of opportunity could emerge at any moment to drive commonsense reforms to address the underlying flaws of our immigration system. As the economic and political costs of an enforcement-only approach mount, Trump could shift the political dynamics on this issue with just one Truth Social message. If this happens, solutions-minded leaders should seize the opportunity and find common ground, even if progress comes in pieces. The country has experienced firsthand the consequences of an all-or-nothing, zero-sum approach to immigration reform; it’s time to try something different, and we hope the lessons and recommendations in this report can help drive long overdue progress.

Appendices

Appendix 1: How the CHNV parole program worked—and why Venezuela was different

Launched in October 2022 for Venezuelans and expanded in January 2023 to include migrants from Cuba, Haiti, and Nicaragua, the CHNV parole program marked a significant evolution in U.S. migration policy. It showed that even modest, clearly communicated lawful pathways can shift migration patterns—when paired with credible enforcement and regional cooperation.

The program addressed both practical and humanitarian realities. Many of these migrants were fleeing authoritarian regimes, gang violence, and economic collapse. In most cases, deporting them posed not only logistical hurdles but also legal risks. International agreements prohibit the return of individuals to countries where they may face persecution—known as refoulement—and the governments of origin often refused to accept deportation flights.

CHNV offered a structured alternative: Up to 30,000 individuals per month from these four countries could apply for temporary parole from abroad, using a digital platform and a U.S.-based sponsor. At the same time, the U.S. secured a parallel agreement with Mexico to accept returns of migrants from these nationalities who entered irregularly. Though implemented unevenly and in limited numbers, this return policy was key for making the program work.

The effect was immediate. For Cuba, Haiti, and Nicaragua, irregular encounters at the U.S. border fell sharply and stayed low, reinforced by the expansion of CBP One appointments and stepped-up coordination with Mexico and regional partners (Figure A1). The success reflected two key factors: first, a credible consequence structure (those crossing illegally became ineligible for parole and subject to removal); second, a preference among migrants to “do things the right way,” when the right way was made available and attainable.

Figure A1. The CHNV Parole Program cut encounters of migrants fleeing authoritarian regimes

Why Venezuela was different

Venezuelan flows proved more complex—due to both scale and circumstance. Venezuela’s displacement crisis was by far the largest in the hemisphere, with over 7.7 million people having fled the country. Managing that volume required not just lawful pathways, but the actions of many countries and actors along the migratory path. CHNV had an immediate effect in reducing Venezuelan flows when first introduced, but the decrease did not hold. Several factors explain why:

- Timing and perceptions. By the time CHNV launched for Venezuelans, many were already traveling through the Darién Gap. Rumors of Title 42 ending fueled fears that the window for legal entry was closing.

- Eligibility gaps. Large numbers of migrants lacked the documents, digital access, or sponsors required to apply for CHNV. In particular, many Venezuelans did not have valid passports, as the collapse of the state had rendered basic services like obtaining and renewing a passport or identity card much more difficult. This meant that for some of the most desperate migrants, CHNV was not a viable option.

- Weak enforcement mid-2023. Mexican enforcement capacity waned midyear due to funding shortfalls at INM (Mexico’s migration enforcement agency), resulting in less interdiction and more unregulated movement through Mexico. After the deadly and tragic fire at the migration detention facility in Ciudad Juarez on March 27, 2023, Mexico’s migration agency paused enforcement altogether for over six weeks. Lax enforcement from Mexico particularly impacted Venezuelan flows due to the limited capacity of the U.S. or Mexico to repatriate Venezuelan migrants.

Over time, two developments shifted the dynamics: First, CBP One appointments became increasingly available, focused on migrants already in Mexico. By mid-2024, 98% of Venezuelans encountered at the border were using CBP One rather than crossing between ports of entry. Second, diplomacy delivered. A December 2023 visit from Secretaries Blinken and Mayorkas secured a renewed Mexican enforcement push, including the restoration of INM funding and more robust internal interdictions. As asylum eligibility tightened in June 2024 and enforcement increased on both sides of the border, migrants began to see that the legal path was now the best path.

Appendix 2: Supporting regional response to the Venezuelan migration crisis: The strategic role of U.S. foreign aid

As Venezuela’s collapse triggered the largest displacement in Latin American history—over 7.7 million people by 2024—the U.S. deployed targeted foreign aid to help countries across the region absorb and integrate migrants. This investment in stability, dignity, and lawful pathways abroad proved far more cost-effective than reacting to unmanaged flows at the U.S. border. The U.S. government committed approximately $3.6 billion in foreign aid across the western hemisphere in the four years of the Biden administration. These efforts included humanitarian aid to respond to the Venezuela crisis inside and outside of Venezuela, support for refugees across the region, the implementation of the Safe Mobility Offices in 2023 and 2024, and development aid to support regularization and integration policies.

In Colombia, where more than 2.8 million Venezuelans have settled, USAID surged over 400 technical staff to support the government’s effort to regularize migrants and issue new ID cards—an essential step to unlocking formal employment, education, and health care. U.S. assistance helped launch integration centers, bolster local schools and hospitals, and expand financial inclusion so migrants could access banking and credit, reducing reliance on informal economies. Programs offered trainings to help media outlets report on crime without stoking xenophobia. Much of this support was provided to communities that welcomed migrants, without differentiation between migrants and native-born residents, which was important to avoid a sense of preferential treatment to newcomers. For instance, the integration centers all provided services to both Colombians and Venezuelans (and other migrants), leveraging existing spaces that were already well known in these communities to expand government service provision.

In Peru, U.S. assistance focused on accelerating migrants’ economic integration. USAID supported efforts to validate professional and academic credentials, enabling Venezuelan doctors, teachers, and engineers to rejoin the workforce faster—reducing dependence on aid and enhancing Peru’s economy.

In Brazil, USAID backed “Operation Welcome,” a nationally coordinated effort that relocated Venezuelans from overwhelmed border towns to interior cities where they were matched with job opportunities, while helping migrants secure housing, documentation, and job training. In Ecuador, humanitarian assistance from PRM (State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration) and BHA (USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance) provided food, shelter, and healthcare, while supporting the government’s rollout of three decrees that created new lawful pathways to regularization for Venezuelan migrants—reinforcing national sovereignty while expanding protection.

Beyond South America, U.S. assistance also supported expanded legal migration from Central America, including additional H-2 temporary work visas, job training, and rights-awareness campaigns, offering alternatives to irregular migration. Researchers found that in communities in Guatemala with higher shares of H2A and H2B visas, only about 11% of families reported having irregular migrants compared to nearly 30% in communities with low shares. Legal migration options were backed by diplomatic engagement and community-level programs to build confidence in the system.

Most importantly, humanitarian assistance from PRM and BHA provided migrants with basic stability—through food, shelter, hygiene, and legal assistance—allowing them to begin the path to regularization in host countries, rather than continuing northward in search of basic needs.

These efforts worked. Regional absorption reduced pressure at the U.S. border while strengthening governance and economic inclusion in receiving countries. At a fraction of the cost of managing migrant flows at the border, U.S. foreign aid helped shift migration from a reactive crisis to a shared, strategic challenge—one better addressed regionally than at the last mile of desperation.

Appendix 3: The rise of private sponsorship in U.S. migration policy

In the past three years, the United States quietly launched one of the most significant innovations in its immigration infrastructure in decades: The expansion of private sponsorship as a tool to welcome displaced people. What began as an emergency measure matured into a scalable, cost-effective model with deep community roots. The Biden administration did not just adjust the traditional refugee pipeline—it opened up new channels of participation for everyday Americans. And in doing so, it expanded both capacity and public trust.

The transformation began in a time of crisis. In 2021, Operation Allies Welcome resettled more than 80,000 Afghans who had worked alongside U.S. forces. Lacking the capacity to handle such a large caseload through the formal refugee system, the administration authorized an alternative model: “Sponsor Circles,” made up of community volunteers, faith groups, and veterans’ networks. These circles provided housing, mentorship, and basic services. The initiative moved quickly and demonstrated that Americans—when asked—were ready to step up. Still, the experience highlighted key gaps: Sponsors lacked clear guidance, coordination with local governments was uneven, and evacuees were left in legal limbo due to the absence of a path to permanent residency.

Those lessons were applied almost immediately. In 2022, the launch of Uniting for Ukraine built on the Afghan experience by pairing humanitarian parole with structured private sponsorship. More than 45,000 Americans volunteered to host Ukrainian families, offering temporary protection, housing, and community support. This time, federal messaging was clearer, digital infrastructure more robust, and public enthusiasm more widespread. Additionally, the parole structure of this program was well suited to Ukrainian migrants, as many hope to return home when the security situation permits. The results were encouraging: Sponsors helped newcomers integrate faster and at lower cost than traditional systems allowed.

Then came the formal leap. In early 2023, the administration launched Welcome Corps—the first private refugee sponsorship program in over 40 years. Any group of five or more Americans could sponsor a refugee, providing basic support for the first 90 days. More than 15,000 Americans signed up in the first year.

Welcome Corps did not replace the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP)—it complemented it. While the traditional system remains essential for high-need and vulnerable populations, it is costly (averaging $7,000–$15,000 per refugee) and limited in scale. In contrast, private sponsorship introduces a leaner, more flexible alternative, reducing taxpayer burden while expanding capacity. Sponsored refugees often achieve quicker employment and stronger local ties. According to Welcome.US, Americans have contributed an estimated $7 billion in time, housing, and resources across all recent sponsorship programs.

The CHNV parole process (for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans) further demonstrated the power of sponsor-based systems. Though not formally part of Welcome Corps, it relied on private U.S.-based sponsors, streamlined digital applications, and community networks to manage large-scale flows with minimal federal infrastructure.

While the concept of private sponsorship was not new, as family and employment sponsorship have been around for many years, the administration deployed it in new contexts and at a greater scale than before. The impact was not just logistical—it was cultural. In red and blue states alike, sponsorship became a vehicle for restoring a sense of agency in a national conversation that often feels polarized and gridlocked. People who know someone who came through the process were more likely to support it.

Appendix 4: An expansion of border processing capacity

While the headlines often focused on deportations and border arrivals, a more technocratic story also unfolded in response to record migrant arrivals at the Southwest border: capacity at the border to process, screen, and remove migrants steadily expanded.

The evolution had two main drivers: increased processing infrastructure and streamlined processes. On the border infrastructure, after an initial decrease, the administration boosted core operational inputs (Figure A4a) such as detention beds, officers and judges, and repatriation flights.

CBP holding capacity, for example, rose from 11,200 beds in FY2020 to 20,000 by FY2024—an essential expansion as surges repeatedly overwhelmed facilities. The administration worked to increase the number of immigration judges and asylum officers to avoid further backlogs. In FY2020, there were 517 immigration judges, but this number rose to 735 by FY2024. The number of asylum officers, however, remained roughly flat—largely due to attrition and persistent recruiting challenges. Despite this, throughput improved in part through procedural innovations including conducting credible fear interviews by phone from CBP custody instead of after release and installing booths and remote adjudication systems to allow officers to handle higher case volumes.

Technology and policy also helped accelerate downstream steps. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) leveraged CBP biometric and vetting systems to issue work authorizations faster, shaving the average processing time from 90 days to 30. In some major destination cities, processing times dropped to less than a day.