The final results of the 2022 midterm election in the United States are in. Journalists tell us that a key issue for voters was preservation of democracy. A recent NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll showed that while inflation was the top issue on voters’ minds, “preserving democracy” captured second place. The issue that claimed little attention was education. Yet, as Thomas Jefferson once said, “An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.” That is, if we care about democracy, we must also care about education.

Only $10 million were spent on education ads by both parties between Labor Day and late October 2022, compared to $103 million spent on abortion ads by Democrats and $89 million spent on tax ads by Republicans. When education was discussed, political scientist Sarah Hill suggests that the topic was narrowly construed around culture war issues, including parental rights and ideologically-driven curriculum changes like banning books.

Sadly, conversation about education was limited in the most recent American election. We desperately need to ignite this discussion.

Given the lack of discussion around education, it is fair to repeat the claim made in 1983 that our nation is at risk. Now more than ever, the populous is required to sift truth from fiction among the many hyperbolic claims made by politicians on both sides. Without strong critical thinking skills, it is nearly impossible to manage the amount of content that people encounter every day and to form cogent opinions—be it on issues like health care, inflation, or climate change.

We are failing the next generation of citizens. Our recent Brookings blog on the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores makes this point. It showed how students’ levels of proficiency in reading and math were already relatively low pre-pandemic, with the important qualifications that NAEP proficiency is not equivalent to grade level proficiency and a high academic standard to achieve. In fact, proficiency on the NAEP requires a deeper understanding of reading and math skills, including the application of critical thinking in relation to subject area content. And many reports suggest that even reaching proficiency (as defining success through the lens of just reading and writing) will not be enough to achieve Jefferson’s vision. Children need to learn a breadth of skills that includes—but goes beyond—content, to go from classroom to career success.

Our recent discussion of education facilitated by Brookings on November 9 following the launch of our book, “Making Schools Work: Bringing the Science of Learning to Joyful Classroom Practice,” explored a comprehensive, but flexible, framework for how to educate children with a breadth of skills—how to educate children to be caring, thinking, and creative citizens for tomorrow. Born from research in the science of learning, we suggest that we must teach in the way that human brains learn through an active (not passive) pedagogy that is engaging rather than distracting, meaningful with clear connections to prior lessons and students’ out-of-school experiences, socially interactive instead of entirely solo, iterative with room for experimentation and trial and error, and joyful rather than dull and repetitive. This is the antithesis of what is going on in many schools across the globe that were fashioned for a bygone era. If we do embrace a more modern educational model, students can be strong across the skills required to navigate school, work and society: collaboration, communication, content, critical thinking, creative innovation, and confidence (the ability to persist even after a failure and to know that you can grow with experience).

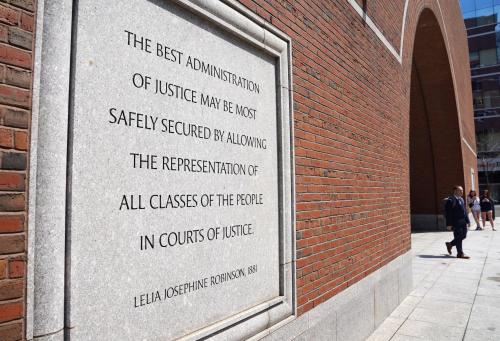

Sadly, conversation about education was limited in the most recent American election. We desperately need to ignite this discussion. If our graduates are to outsmart the robots, to be viable for the job market, and to be discerning voters and citizens, education must literally be on the ballot. Yes, a major issue for voters this year was the precarious nature of our democracy. Our democracy, however, cannot survive if we do not educate our citizens. As The Atlantic proclaimed, “Democracy was on the Ballot and Won.” If it is to keep winning, we must discuss education reform. Our science of learning can lead the way. It is imperative that children learn a breadth of skills that they can carry with them into the voting booth.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Let’s educate tomorrow’s voters: Democracy depends on it

November 21, 2022