What are the barriers stopping doctors from using the best treatments for patients?

When people have back pain, doctors may recommend physical therapy, pain control, and occasionally, surgeries like “spinal fusion,” in which the doctor joins together two or more bones in the spine to prevent movement between them. One would think surgery is a last resort, but it appears that economic incentives may encourage overuse.

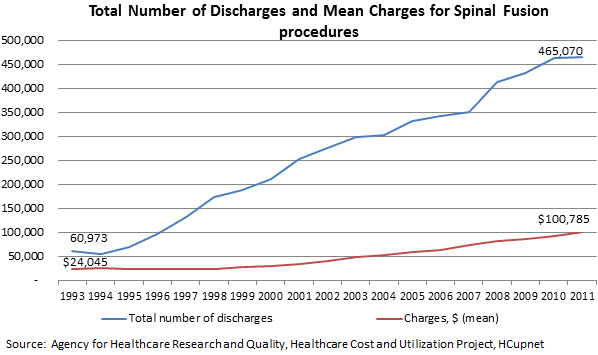

A recent government study found that rates of spinal fusion procedures increased when doctors were investors in distributors of spinal devices, such as plates, screws, and rods. This study suggests that doctors tend to recommend spinal fusions more when they also benefit from the sale of equipment for the procedures. In addition, an article by The Washington Post found that one particular surgeon in Florida had performed many surgeries and received hundreds of thousands of dollars in incentive payments. While the hospital where the surgeon worked had been warned about his high rate of surgeries, the hospital did little to limit the number of procedures. However, a hospital compliance officer has since brought a lawsuit against the hospital but the surgeon has not been disciplined. Out of 10 spinal fusion procedures that this doctor had performed, nine were deemed to be not medically necessary by an independent review—in other words, those patients should have gotten physical therapy or other less invasive treatment. Though few surgeons are as problematic, it’s likely that back pain is regularly over-treated with surgery. The number of spinal fusion procedures has grown from nearly 61,000 in 1993 to 465,000 in 2011, as this graph shows. It’s hard to believe that patients really need ten times as many hospitalizations, and spend nearly five times as much on these procedures, today compared to twenty years ago.

Invasive procedures may not be the best treatment option for the patient and often increase the cost of treatment for the patient and in the health care system. The American Medical Association has noted that there are areas other than spinal fusion procedures where overuse could be a concern for patient safety, such as the use of antibiotics for upper respiratory infections, blood transfusions, and early-term delivery.

Most doctors care a great deal about patients, train for many years, and take an oath to “first do no harm.” And yet, something about payment incentives appears to harm their judgment. The consensus among health policy experts is that the way in which doctors get paid contributes to these problems. Today, doctors get paid on a per-procedure basis, often called “fee-for-service” (FFS). The more procedures they do, the more they get paid. Such a system does not consider outcomes to patients or payers; it only rewards quantity. For example, under the current system, a physician would be paid based on the number of procedures he or she performs regardless of the outcomes of the patient. Under a “value-based” system, a physician would receive payment based on the patient’s later health status.

The good news is that good alternatives exist, and hopefully will become more common.

How to improve incentives

Let’s take one example of more comprehensive care. The Spine Center at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center is an example of an integrated care system that addressed the problem of engaging physicians in treating patients suffering from spinal problems. It’s a single building with one-stop shopping, where patients with back pain get a complete evaluation by physical therapists, neurologists, orthopedic surgeons, and pain control specialists, depending on an initial screening. They also get the right x-rays or imaging procedures. This is termed “a multidisciplinary approach” to spinal care where many types of doctors and other providers are involved in a patient’s care, including non-medical issues such as mental health or workforce participation that are typically not provided by physicians. Complementing this team-based approach, the Center design its payment structure so that physicians would work together to improve a patient’s care. By changing the incentives for physicians, the Spine Center could reduce the competition among doctors’ departments and incentivize non-surgical treatments to provide the best care for the patients.

Clearly, this is a great way to deliver care. But how can one make a business case for such care, since it may actually make less money for the health system? This is where payment reform comes in. Payment reform is a complicated process but it makes sense to pay doctors for the care they provide and to make sure that complicated and expensive procedures will improve a patient’s health. For example, one way to save money while providing patients with better care would be to pay doctors with a “bundled payment.” A bundled payment would pay for all of the services provided in a patient’s episode of care, rather than just paying separately for each individual service or procedure. This way, all of the doctors involved in a patient’s care, such as both a surgeon and anesthesiologist for a surgery, are motivated to work together and to cut back on any unnecessary surgeries or treatments that don’t ultimately help a patient. Rewarding doctors for taking good care of their patients, rather than for the number of procedures they perform, is an important part of current payment reform efforts.

An important part of payment reform is making sure that Medicare and other insurers can measure whether providers are helping their patients. Medicare uses quality measures, which evaluate a provider’s performance in providing care, such as helping a patient control their high blood pressure or screening a patient for colon or breast cancer. Quality measures can help physicians judge how their performance compared to their peers and to give them the motivation to improve the quality of the care they provide. They can also be tied to payment, so that a physician who screens his patient for cancer, among good performance on other measures, can get a bonus payment. Tying quality measures to payment can help make payment reform easier and more widely adopted as doctors have greater motivation to improve their patients’ care.

Can better treatment guidelines help doctors and patients?

How else could doctors do what they know is the right thing for patients? Fixing perverse payment incentives is a good start. Better payment allows better care. In a system where payment is based on the value and not the volume of services, doctors ideally also adhere better to “best practice” guidelines—that is, commonly accepted protocols. Adhering to these guidelines, in complement to payment reforms, could help reduce the number of procedures that doctors provide. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included bundled payments in the hopes that it would lead to more coordinated, higher quality care while reducing costs. Medicare is moving forward on testing bundled payments to different types of health care providers through the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative (BPCI). These payment reform demonstrations build upon earlier work on the Medicare Acute Care Episode (ACE) demonstration, where providers received an overall payment for an episode of care with the goal of improving the efficiency and quality of care for Medicare patients. With the provisions of the ACA that promote greater care coordination and a movement away from FFS, payment reforms are likely to be more and more common in the future.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

It’s Likely Back Surgeries Are Done Too Often. Can Doctors Do Better?

November 14, 2013