Israelis will go to the polls on March 17 to elect the 20th Knesset, Israel’s parliament, which will then form a new government to replace Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current one (he hopes to head the next government as well.) We are following the run-up to the elections in a series here on Markaz, the blog of the Brookings Center for Middle East Policy.

Amid the furor over Benjamin Netanyahu’s planned speech before a joint session of Congress, scheduled for March 3, domestic Israeli politics are frequently referenced. What is the political consideration behind the planned speech? Is Netanyahu playing pure politics here, or does he have a legitimate case to be made before Congress? Will the speech help him in the upcoming Israeli elections or will the dramatic backlash against the speech hurt him in the polls?

Despite appearances to the contrary, Netanyahu has generally had a very good political week.

Substance: Iran

To be clear, the substantive issues at hand are far more important than the effect on the March 17 polls in Israel. A potential deal between the P5+1 and Iran is of far greater strategic consequence. Netanyahu’s dramatic snub of the president, and the Democrats more broadly, could strengthen the possibility that Israel will gradually become a partisan issue in the United States—anathema to Israelis who care deeply about bipartisan support in Washington. Even the shorter-term relations with the Obama administration are ultimately far more important than the marginal electoral effect of any campaign stunt.

On substance, there actually is a case to be made for a Netanyahu speech if one believes two assumptions, as Netanyahu and Israeli Ambassador to the U.S. Ron Dermer both do: First, that a deal between the P5+1 and Iran in the current contours (on which Israel is routinely briefed) would be a national security calamity for Israel. Second, that a deal might be imminent.

If a deal is impossible to reach, then Netanyahu and Republican members of Congress are in essence volunteering to take the blame for the failure of the talks by calling for new sanctions, rather than letting the blame rest where it rightly should—squarely on Iran’s shoulders. But a deal—or the framework of one—may in fact be taking shape. Given Netanyahu’s sincere belief about the gravity of that possibility, coming to Washington to try and stave it off makes some sense, despite the palpable damage to Israeli diplomacy and the possibility of future damage to bipartisan support for Israel.

Politics: Agenda and Optics

Nonetheless, politics are certainly playing a role. The speech was carefully scheduled to coincide with the annual AIPAC policy conference which will be held at the beginning of March, just two weeks before the Israeli elections; in a recent survey of Israelis conducted by the Israeli Democracy Institute and Tel Aviv University a clear majority of respondents believed the elections were central to the timing of the speech.

In political terms, Netanyahu has two main considerations:

First, by shifting the debate to foreign policy and national security, Netanyahu is playing on his own turf. As I noted in a previous post, the Zionist Union (headed by the Labor Party) needs to shift the debate towards the economy and domestic issues. Netanyahu, conversely, holds a strong advantage on national security both because of the weight of his experience and because the views of the median Israeli voter on national security are closer to his than to Herzog’s. Shifting the debate toward Iran—or toward recent tensions on Israel’s northern border—is a clear win for Netanyahu. A dramatic speech in Washington definitely won’t hurt in this regard.

Events may further strengthen this shift. If a framework deal is struck between the P5+1 and Iran before the Israeli elections, Israeli voters will naturally want to hear from their candidates, first and foremost, about the contours of the deal and how Israel should adjust its policy going forward. Netanyahu is sure to take a very critical view of such a deal; the opposition may be more circumspect, but it will be challenged by what appear to be significant U.S. concessions in the negotiations.

If Iran, as a topic, is politically advantageous for Netanyahu, the rift with the United States is not. As a rule, Israelis do not like their prime ministers to quarrel with the United States. In the poll cited above, over 55 percent of respondents said Netanyahu should have declined the invitation to speak in Congress.[1] Respondents were split on whether Netanyahu’s trip damages Israel’s national interests.

The rift with the Obama administration is nothing new, however. It is likely that whatever political damage Netanyahu suffers from the frequent quarrels with the administration, it is already embedded in his numbers. It is simply not news that the president is displeased with Netanyahu, although the gravity of this crisis among congressional Democrats is not duly appreciated in Israel.

Second, in practical campaigning terms, what most voters will see is not the intricacy of policy or partisan debates in Washington, but the spectacle of the prime minister speaking—in impeccable English and with an impressive baritone voice—to the applause of hundreds of legislators in the august setting of the U.S. Congress. If any image could convey the difference in gravitas between Netanyahu and his challenger, it would be this.

Enter Biden: In political terms, therefore, the question is whether the spectacle lives up to its promise. News that Vice President Biden, who presides over the Senate and typically sits behind the podium on such occasions, will conveniently be unavailable for Netanyahu’s speech due to yet-unknown foreign travel plans, may change the calculation. If the vice president’s chair, within the TV frame, is occupied by the president pro tempore of the Senate—Republican Orrin Hatch of Utah—rather than Biden, that could become the focus of the speech. If a considerable number of Democrats are visibly absent, that too could hurt the spectacle.

Numbers

Given Bibi-Boehner-gate, and the polling cited above showing that Israelis prefer that Netanyahu cancel the trip, how has Netanyahu faired in the past week?

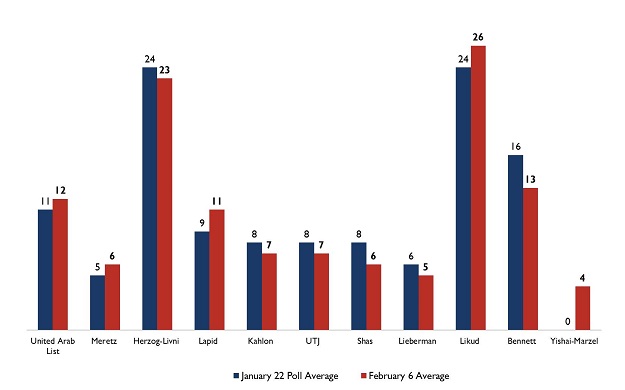

In general, Netanyahu has had a very good couple of weeks. Revisiting some of the figures from the previous post it is apparent that Netanyahu has maintained his lead in the raw numbers; if anything, the momentum Herzog and Livni had following the announcement of their joint ticket has stalled, while the Likud is now on the rise in most polls.

Figure 1 [2]

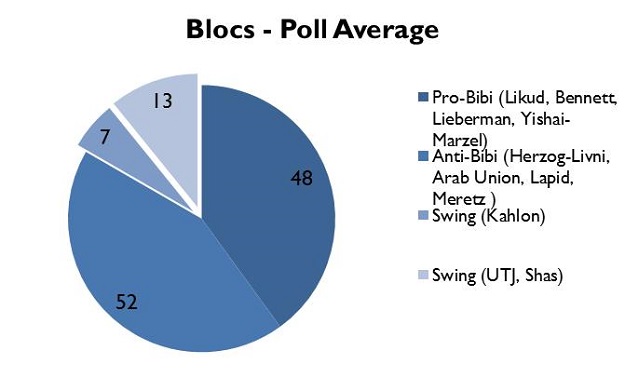

More importantly, however, the key to a possible Herzog victory, as I discussed in the previous post, was the role of the swing parties, and in particular Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu and the Ultra-Orthodox Shas and United Torah Judaism (UTJ). Lieberman this week broke with his previous centrist stance and made clear he would not support a “leftist” government (i.e. one headed by Herzog). He noted that this was unlikely anyway, which may explain his shift toward courting his own right-wing base.

UTJ, moreover, reiterated its commitment not to join in a coalition alongside Lapid—a prerequisite for a Herzog coalition noted in the previous post—with Shas more or less following suit. These commitments are not sacrosanct, but they certainly dampen the mood in the Zionist Union.

Figure 2

The upshot is that the chances of a Herzog coalition are, at present, small, and the battle seems to be—until the numbers change again—between a Netanyahu-led national unity government (which Meretz, for example, opposes, but which Herzog and Livni have yet to rule out), and a narrow right-wing government led by Netanyahu.

If the uproar over the Bibi-Boehner-gate has had a political effect in Israel, it has not been—thus far—discernably bad for Netanyahu.

[1] The question stated that “[A]ccording to clear American protocol, heads of state [sic] do not make officials visits to Washington a short time before elections in their own country…”, which may have skewed the results toward the negative.

[2] The poll average again draws on data published by Haaretz.co.il.

The chart differs from last week’s in two regards. First, Kadima has dropped out of the race and Shaul Mofaz has retired (for now—Israeli politicians are never far from un-retirement). I accordingly removed Kadima from the chart.

Second, Eli Yishai, the former chairman of Shas and former deputy prime minister, has disgraced these elections by joining forces with Baruch Marzel, former chairman of the Kach party, founded by Meir Kahane, which was outlawed as a terrorist organization by both Israel (in 1994) and the United States after being barred from running in Israeli elections due to its blatant incitement to racism. Yishai was always very right-wing but completely within the bounds of legitimate politics. Baruch Marzel and his current party however, sit firmly beyond the pale.

Yishai and Marzel’s party is now accordingly placed at the extreme right end of the scale in the Figure 1.

The result of this alliance is that Yishai now draws on the electorate of the most extreme right, and with them passes the minimum threshold (albeit barely), strengthening the overall right-wing bloc but weakening other parties within it, including the Jewish Home of Naftali Bennett.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israeli elections: The politics of Bibi’s Congressional speech

February 7, 2015