When you are a leader of a low- to middle-income country, tasked with improving the lives of thousands and sometimes millions of citizens, the temptation to take a few shortcuts to propel your country to high-income status might be high. After all, even at high rates of economic growth, catching up to a standard of living of developed economies is a long process that often requires current generations to make certain sacrifices for the well-being of future generations.

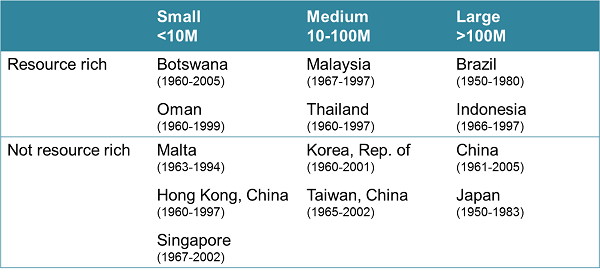

The 2008 Commission on Growth and Development report by Michael Spence and other influential thinkers identified 13 countries that sustained high levels of economic growth exceeding 7 percent per annum for at least three decades. This means that these countries multiplied their economic might eightfold because according to the rule of 72, a decade of 7.2 percent of growth would result in a doubling of the economy.

When we take a closer look at these countries, we notice surprising diversity: Small countries like Malta and Botswana performed equally as well as large countries like China and Brazil; countries lacking rich natural resources were able to grow at comparable levels with their resource-rich counterparts. As one economist put it, there are many recipes to achieve economic growth, and those countries that adjust these policy recipes to their own realities are the most successful.

Table 1: Every country can grow at high levels (periods of high growth in parentheses)

Source: Own compilation based on The Growth Report

Over the past 20 years, Western Balkan countries—Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Croatia—followed a development model that skips an important step. As their economies transformed from being primarily agriculture-based, labor moved directly into the service sector, bypassing industry and manufacturing. Manufacturing output decreased from 15 percent of GDP 20 years ago to 12 percent today while services increased from 48 to 63 percent of GDP over the same period. Services now account for the largest share of total output and employment, which is characteristic of post-industrial, high-income economies. However, the all-encompassing services category includes primarily low-skill trades rather than sophisticated, higher value-added services.

Are there any lessons that the Western Balkan countries can glean from Table 1?

Only two countries with comparably small populations—Botswana and Oman—have gone through a period of sustained economic growth without advancing manufacturing production, and both countries have been able to draw upon their ample amounts of natural resources. On the other hand, the so-called East Asian Tigers—often cited for their sustained high economic growth—all had targeted industrial policies to spur export-oriented manufacturing production. The four tigers, for example, increased their manufactured exports from $4.6 billion (in relative value to 2000) in 1962 to $715 billion in 2004. India, the often cited poster child for service sector-led economic growth, is notable missing from the list. In fact, the Indian prime minister announced plans to expand manufacturing production with his “Made in India” campaign.

These developments show that manufacturing is a great strategy to advance economically, especially if you are close to a large consumer market like the EU; however, it is not the only strategy. Today, services are becoming increasingly tradable. They have become the new “growth escalator” in many countries.

In the Western Balkans, information and communications technology and tourism are among the service sectors with great potential to grow and create many more jobs. Over the last 20 years, the services sector is the only one to have created net jobs globally (plus 3 percent). By contrast, and despite East Asia’s industrialization, global industrial jobs growth is down (minus 1.2 percent). Services-led growth is also more inclusive and sustainable. It’s increasing the participation of women in the labor force and easing the dependency on natural resources. This service revolution is connected to changes in manufacturing itself, which is becoming much more knowledge-intensive, making the border between manufacturing and services more porous and opening up opportunities for countries that are developing a strong services base.

While there are no shortcuts to development, it is comforting to know that there are many paths that can lead to economic success. As long as the Western Balkan economies have a genuine commitment to growth and inclusion, are willing to learn from other countries’ successes, and adjust the lessons learned to their own economic and political realities, there will be many roads to prosperity.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Is there a shortcut to development for the Western Balkans?

May 26, 2016