Below is a viewpoint from Chapter 6 of the Foresight Africa 2019 report, which explores six overarching themes on the triumphs of the past years as well as strategies to tackle the remaining obstacles for Africa. Read the full chapter on boosting trade and investment.

What do India, Turkey, Japan, China, and the European Union have in common with Africa that the United States does not? Each country and the EU have held two or more summits with African heads of state. While there were positive aspects in the Trump administration’s Africa strategy that was released late last year, there was no mention of a U.S.-Africa summit. Does this matter?

Frequently mistaken for little more than photo opportunities, summits foster regular interaction between governments, business, civil society, and other interested parties at various levels. Summits also signal a clear policy priority of participating governments. As a result, they are an important vehicle for advancing national interests.

For example, over the course of six Africa-EU summits (the most recent being in Côte d’Ivoire in November 2017), European and African leaders have addressed a number of issues including trade, migration, peace and security, and technological innovation. The summit process has also brought together leaders from civil society, business, youth, and female entrepreneurs.

The results have been substantive: (1) The EU has developed a trade strategy that gives European companies and products preferential access to the region’s market. (2) On the priority issue of immigration, the European Commission will soon build a $5.8 million facility to improve the relationship between African diaspora organizations and their country of origin. (3) Endorsing the recently concluded African Continental Free Trade Agreement, European Commission chief Jean-Claude Juncker said that he envisions the creation of a “continent-to-continent free trade agreement between the EU and Africa.”

Ongoing senior U.S. engagement with African leaders has been minimal at best during the current administration.

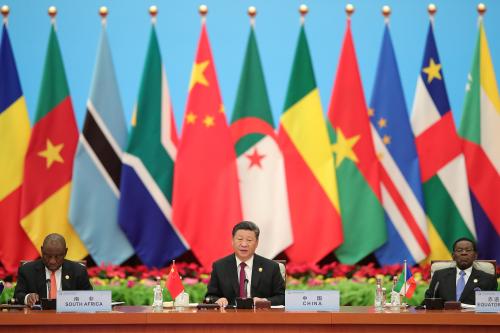

The China story has generated even more substantial headlines. After sustained high-level engagement starting in 2000, the first formal summit, the Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), took place in 2006 in Beijing where President Hu Jintao pledged $5 billion of concessionary loans to Africa. Over the course of five FOCAC summits in which virtually every African head of state has participated, China has become Africa’s largest trading partner, and, at each of the past two summits, Chinese President Xi Jinping has pledged $60 billion in financing. There are also a number of related meetings, such as between Chinese and African foreign ministers on the margins of the U.N. General Assembly and in the first ever China-Africa Defense and Security Forum.

In contrast to the EU and China, the U.S. held its first ministerial in 1999, when former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and nine U.S. cabinet officials hosted 180 ministers from 43 African countries to discuss a “Partnership for the 21st Century.” While there were several subsequent meetings, the only summit occurred in 2014 when former President Barack Obama hosted leaders from 50 African states, resulting in $14 billion worth of commitments from U.S. companies to invest in Africa. President Obama also convened a U.S.-Africa Business Forum several months before leaving office.

Apart from former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s meeting in Washington with 37 foreign ministers in 2017, President Donald Trump’s lunch for a group of Africa leaders on the margins of the U.N. General Assembly in 2017, and White House meetings with President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria and President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya, ongoing senior U.S. engagement with African leaders has been minimal at best during the current administration.

There is no question that the architecture of U.S. Africa policy is impactful. This includes the African Growth and Opportunity Act, the President’s Program for Emergency AIDS Relief, the President’s Malaria Initiative, the Young African Leaders Initiative, Power Africa, Feed the Future, the Trade and Investment Hubs, and the Millennium Challenge Corporation.

With the passage of the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act in October last year, which provides for the establishment of the $60 billion U.S. Development Finance Corporation, the Trump administration has supported the emergence of an important new agency that is likely to boost U.S. investment in Africa. USAID’s Private Sector Engagement Policy is likely to further increase U.S. commercial engagement on the continent.

However, without the active engagement of the most senior levels of the U.S. government on a regular and sustained basis, the U.S.-African relationship will not achieve its full potential.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Is the US keeping pace in Africa?

March 4, 2019