This paper was presented at the Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER) conference in Tokyo, October 2017. All the conference papers are available here.

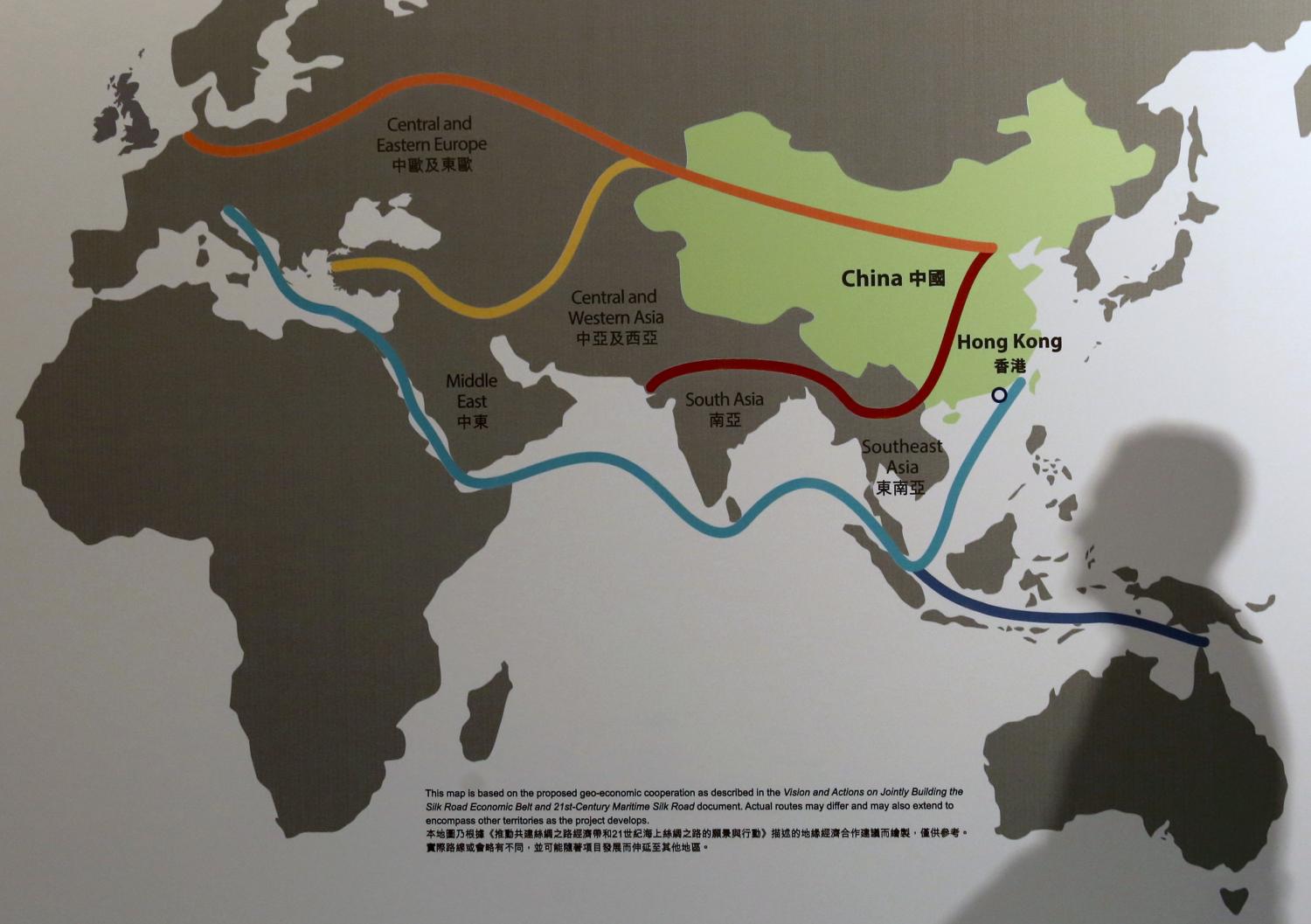

China in recent years has become a major funder of infrastructure in the developing world. The big Chinese financing push started shortly after the global financial crisis (GFC). Starting in 2013 China “branded” the program under the rubric of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In speeches in Kazakhstan and Indonesia, President Xi Jinping proposed the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The former refers to the ancient overland Silk Road between China and Europe. The latter is a vaguer concept that in practice seems to incorporate the whole world. The BRI involves issues such as policy coordination and harmonization of standards, but at its heart is infrastructure financing.

In his opening remarks at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May 2017 President Xi noted that:

“Infrastructure connectivity is the foundation of development through cooperation. We should promote land, maritime, air and cyberspace connectivity, concentrate our efforts on key passageways, cities and projects and connect networks of highways, railways and sea ports.”

The initiative has been met with enthusiasm by many developing countries, who see new opportunities for financing needed infrastructure. Some nearby countries such as India, on the other hand, have reacted with caution as they question China’s strategic motivations. Developed countries of the West have also been reticent to endorse the program until they learn more about the details. A concern of Western countries is that China’s efforts will undermine global norms, especially in the areas of debt sustainability and environmental and social safeguards.

This paper examines China’s role in development finance and in particular addresses the issue of whether China is challenging global norms. China’s effort is recent and data problems are legion. Given that the initiative is popular in many locations it is odd that China is so secretive about the lending amounts, terms, and specific projects funded. Most of the lending is coming from two big state-owned policy banks, China Development Bank and China EXIM Bank. It would be straight-forward for them to publish up-to-date data on lending to different countries, including the terms. In the absence of that kind of transparency, researchers have to make heroic efforts to compile their best estimates. The paper uses recently published AidData to paint a picture of the scale of Chinese financing and where it goes in terms of countries and sectors. Total lending to developing countries appears to be about $40 billion per year in the recent period, an amount that is significant and consistent with China’s overall balance of payments. Geographically, the lending is not particularly targeted to the belt and road; much of it is going to Africa and Latin America. Also, the lending is uncorrelated with measures of risk such as political stability or rule of law.

The paper also takes up the issue of debt sustainability. The countries receiving significant finance from China vary significantly in the quality of economic governance. Some have very good governance, and some, quite poor. Not surprisingly, some of the countries with poor governance are beginning to have problems servicing their external debts. This raises some important questions of global governance: will the troubled countries go to the IMF, as has been the practice in the past? Will China change its behavior as recipient country debt reaches unsustainable levels?

Another important global issue is environmental and social safeguards in infrastructure projects. Most large projects have environmental risks and involve resettlement of communities. The multilateral development banks (MDBs) have developed through experience a set of rules and procedures for assessing and mitigating risks. Many client countries, however, find these procedures cumbersome and extra-legal. It is a fact that the MDBs have become very slow in the construction of infrastructure, and the clients had turned away from this source of finance even before China came on the scene. China’s approach is to follow the laws and regulations of the country in which it is operating, which is a reasonable position. However, in some countries with poor governance regulations are mostly honored in the breech. How is the Chinese approach playing out on the ground? And is there evidence of any shift in the Chinese approach?

Most of the action up to now has come from CDB and EXIM. An interesting recent development is the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a Chinese-led MDB that has quickly attracted 56 member countries. In two years of operation AIIB has lent about $3 billion, a very small share of China’s development finance; and three-quarters of the projects have been co-financed with the other MDBs. AIIB’s lending will grow over time, however, and has the potential to directly and indirectly address some of the concerns about Chinese practices.

The bottom line: It is too early to make a definitive judgment on whether China’s finance is a challenge to the global economic order. There are certainly things to worry about such as growing indebtedness of some of China’s big clients and environmental and social safeguards on the ground. But there are also signs of evolution. China stopped new funding for Venezuela, which is the most problematic of its major clients. Several of the major borrowers from China have turned to IMF programs, which is the traditional medicine for unsustainable debt. Chinese companies and lenders have been given voluntary environmental and social standards by the Ministry of Commerce, which is a step in the right direction. Most encouraging, AIIB is off to a good start and may bring about improvements in the operation of the whole MDB system.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).