“Please don’t destroy my business. It is Black-owned.”

These and similar words were emblazoned on storefronts across the country during the civil unrest following George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020. Black business owners hoped this plea—directed at those who were looting and damaging commercial real estate amid the protests—would not be drowned out by the unrest and frustration.

Embedded in such signs is a unique investment thesis and value proposition: When Black people own stores and other commercial real estate, members of the community will patronize, protect, and respect those businesses in a different way. That is, Black-owned businesses will be strongly supported by Black communities, and Black communities will feel more enfranchised if they have a stake in local business.

So, is this assumption true?

To find out, Brookings Metro is collaborating with developers and community partners in Baltimore, Cleveland, and Detroit as they attempt to “buy back the block.” Specifically, our new Buy Back the Block Lab is studying and advising the efforts of a cohort of community-based, mission-driven investors as they purchase commercial real estate in corridors within majority-Black neighborhoods.

The racial ownership gap precedes the racial wealth gap

In a 2022 analysis, Brookings scholars found that few Black households own commercial real estate (CRE), especially if we exclude rental properties: Only 3% of Black households own nonresidential CRE, compared to 8% of white households. For households that do own CRE, the average white household owns $34,000 of it, compared to just $3,600 for the average Black household.

Nonresidential CRE includes neighborhood retail shops on Main Street, downtown offices, waterfront warehouses, and more. Ownership of these income-generating assets—the management of which also shapes the vibrancy of communities—is extraordinarily concentrated in the hands of a few. In fact, 81% of the value of nonresidential CRE is owned by the top 1% of households that own any. In comparison, for owner-occupied housing wealth, the top 1% owns only 16% of the value.

This is a major missed opportunity for Black wealth-building, given that nonresidential CRE generated $512 billion in revenue in 2020. Income concentrated so heavily in white owners contributes to a wealth gap that sees the median white household hold $188,200 in wealth—7.8 times that of the median Black household ($24,100).

However, there’s more to the story. Not only is CRE ownership very unequal by race, but all CRE owners in Black neighborhoods are impacted by devaluation. Our research found that storefronts and shopping centers in communities with higher shares of Black residents are valued measurably lower than otherwise comparable properties in communities with fewer Black residents.

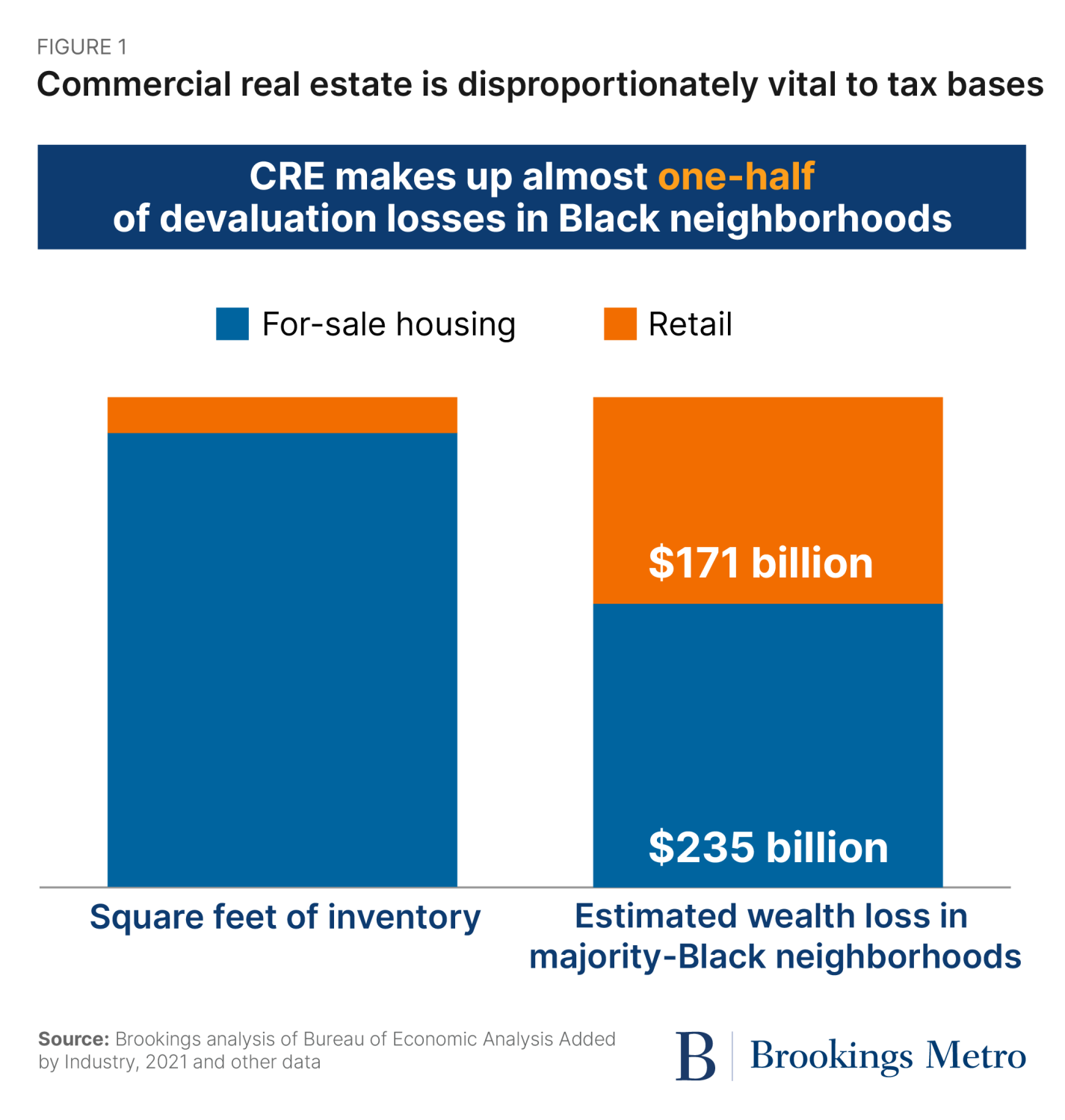

After accounting for predictors of CRE value, we estimate that retail space is undervalued (as directly measured by asking rents and holding capitalization rates constant) by 7% in majority-Black ZIP codes. This means that CRE owners in majority-Black ZIP codes are getting less rental income than they otherwise should, as well as generating less taxable value, resulting in significant revenue loss for individuals and places. We estimate that the undervaluation of majority-Black ZIP codes results in aggregate wealth losses of $171 billion in retail space for the owners of these properties.

These losses represent a real warping of the incentives that CRE owners respond to. In addition to the direct loss of access to the billions of dollars in capital estimated in this analysis—capital that could serve as collateral to finance growth or intergenerational wealth-building—a systematic negative differential in the valuation of property in Black neighborhoods renders these communities vulnerable to speculation and neglect. Devaluation reduces the carrying costs of real estate, and can thus be exploited by investors with greater access to capital who can afford to acquire properties and hold them (if they are anticipating changes in the economic and racial makeup of the neighborhood, for example). Per the collateral point, devaluation also reduces owners’ access to capital for maintenance and improvements, leading to stagnation and decline that further accelerate devaluation.

Can this cycle be broken by changing who owns the properties? Brookings and the neighborhood cohorts are developing innovative ownership models to apply to real CRE assets in their communities in order to articulate and test a multifaceted investment thesis and value proposition. Will increasing the proportion of Black people who own the homes, businesses, and buildings in majority-Black neighborhoods…

- Give those owners greater ability to raise the value of those assets?

- Directly increase the wealth that individuals and communities can accrue?

- Make communities safer?

- Empower Black communities to combat the devaluation of assets stemming from negative perceptions of those neighborhoods, as expressed through both asking rents and tenant location decisions (i.e., retail redlining)?

Given the wide racial gap in business wealth and concerns about gentrification and “development without displacement,” we believe there is a broad public interest in finding out if these hypotheses are true. One direct stakeholder is local government, since they rely heavily on assessing and taxing property to provide services—from public education to police and fire protection, parks, and more—and must also deal with the challenges tied to neighborhood decline and perceptions of decline.

Why local governments want to help ‘buy back the block’

Previous research by Carlos F. Avenancio-León and Troup Howard found that Black and Latino or Hispanic Americans face a 10% to 13% higher tax burden for the same bundle of public services, due in large part to the devaluation of homes in Black neighborhoods. In other words, because of devaluation, local governments in Black and brown jurisdictions have to charge higher tax rates in order to raise the same amount of revenue needed to provide services. What at first might seem like a boon to an individual homeowner—a lower assessment means less taxes owed—becomes a burden when devaluation is systemic throughout a community, as tax rates must increase. In addition, over the long term, the homeowner has access to less equity to leverage. Our research on the devaluation of CRE contributes another major explanation for the fiscal distress of Black communities.

Aggregate wealth losses of $171 billion in retail space impact not just the owners of the properties, but the localities that rely on property tax revenue to fund services. By comparison, owner-occupiers of housing lose an estimated $235 billion in majority-Black ZIP codes.

Commercial real estate—which includes all income-producing property, such as retail, office, industrial, and multifamily rental residential property—plays an important role in balancing local government budgets. Property taxes are in aggregate 31% of all revenue that state and local governments rely on, so any destabilization of this funding source has a negative fiscal impact on jurisdictions’ ability to provide services—especially education, which is the top state and local government expenditure. The tax burden that devaluation places on Black communities may be a reinforcing cycle, because taxes affect both property values and the borrowing capacity of buyers. These communities are trapped in a paradox of under-valuation and over-assessment, and elected officials struggle to balance the need to raise revenue today against stewarding value.

Ending CRE devaluation in Black neighborhoods would take pressure off residential real estate and help both residents and the jurisdictions that serve them. However, in order to avoid commercial gentrification, increasing the share of Black CRE owners is a necessary part of the solution. Any increase in CRE assessed value would ultimately be tied to higher asking rents for business tenants in majority-Black neighborhoods. Therefore, any equitable solution to the systemic devaluation of assets in Black neighborhoods must restore value to the people and communities that are, literally, losing equity.

The Buy Back the Block Lab

We know how conventional CRE practitioners create investment theses, conduct market research and due diligence, assemble capital, and obtain site control. What needs to be done the same way—and what needs to be imagined differently—in order to “buy back the block” with the assets we have and without gentrification and displacement?

The Buy Back the Block (BBtB) Lab is working with local leaders in Cleveland, Detroit, and Baltimore to scope projects and answer these questions. With Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, the Harvard Community Services Center, the Grandmont Rosedale Development Corporation, and Invest York Road, we will help assemble the team of professionals needed to conduct due diligence, structure debt financing, garner government grants and approvals, and attract community investors.

So, who is the “community” that investors come from, and how many are needed? As part of this project, we are exploring concepts to democratize CRE and move beyond the conventional ownership model. There are already many existing models of shared ownership, including community land trusts, employee-owned businesses, and housing cooperatives. However, the BBtB Lab approach will differ from these efforts in that its principal purpose is to help individual residents and local entrepreneurs create wealth through buying an appreciating CRE asset, rather than preserving affordability of space. The Lab will provide advice, data, and support for potential developers, investors, and operators at promising sites in each participating community. While recognizing the urgency of the wealth gap, we will take a patient mindset that begins with understanding the deal potential, getting site control, and acknowledging the long-term financial return horizon. The goal is not just to conduct a transaction, but to practice community-centered economic development that is holistic and considers both neighborhood residents who live and shop locally as well as the entrepreneurs who create small businesses, in order to design inclusive CRE investment vehicles.

In addition to identifying and structuring deals, the Lab will investigate the role of nonprofit intermediaries in facilitating Black CRE ownership, as well as what state and federal economic development policies can help break the cycle of devaluation. Everything we learn will be published in a final “playbook” for communities nationwide who are looking for new ways to practice community-centered economic development.

We hope that results from the BBtB Lab will help many more members of the Black community earn a nest egg with real estate assets that gain meaningful value over time, so that they can send their children to college, set aside retirement funds, make a down payment on a home, reinvest in their home, expand a business, or otherwise realize their financial goals. Over time, we expect to learn lessons that are relevant beyond Black communities. As our colleague Tonantzin Carmona—an expert on Latino or Hispanic wealth-building—has observed, there is a clear demand for alternative wealth-building opportunities and products among groups that feel excluded or do not trust traditional financial services. If tangible, secure, and vetted opportunities are not available, predatory mechanisms will continue to thrive—and gaping wealth inequalities will persist.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).