Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

An IndiaSpend article on 8 September 2016 quotes the Brookings India report titled “Coal Requirement in 2020: A Bottom-up Analysis“, which indicates that even by a generous estimate, the country’s need for coal will not exceed 1.2 billion tonnes over the next four years, as opposed to the Government of India target of 1.5 billion tonnes by 2020.

The article shows how the report calculates India’s future coal requirement:

How much coal will we actually need by 2020?

To estimate India’s coal needs after six years, the Brookings report focuses on three sets of data:

1. Base growth rate: In this case, the report analysed two different scenarios:

a) Scenario 1: Non-power-sector demand was extrapolated based on gross domestic product (GDP) and assumptions were made that demand and production would be elastic–responsiveness of production to rise in demand and prices. Power demand was calculated on upcoming thermal power capacity (examining all plants under construction, their locations, technology, and status, assuming a similar plant load factor (PLF)—or the capacity utilisation of a power plant–as in financial year (FY)’14-15. Assumptions for the non-power sector include the following: 8 per cent GDP growth, respective sectoral GDP changes due to supply and demand and continued imports proportionate to imports in the base year FY’14-15. This scenario puts the estimate at 1,311 MT.

b) Scenario 2: The non-power-sector demand was kept the same as scenario 1. A power-demand calculation was made assuming i) no power cuts by 2020 b) electrification to unconnected rural consumers and reduction in distribution losses. This scenario pegs the estimate at 1228 MT, a more realistic figure, as per the report.

2. High Coal: This method, which pegs India’s coal requirement at 1,291 MT, is optimistic and assumes no imports of thermal coal (coking coal–used to primarily manufacture steel–imports, however, are assumed to continue), a high GDP growth of 8 per cent, 100 per cent electrification with no power cuts, and a modest growth of renewable energy. The assumption is that renewable energy does not displace coal very much as a source of power generation.

Although the health costs to India of using coal to generate electricity are about $4.6 billion (Rs 29,400 crore) annually, which is the cost of setting up five power plants of 1,000 mega watts (MW) each, or 2% of India’s installed capacity, every year, India may have little option but to focus on coal as the primary source of electricity, with the need for coal-fired electricity estimated to increase three times by 2030, as IndiaSpend reported in May 2015.

Coal generates over 75 per cent of India’s electricity and is among the cheapest energy sources available. But its main advantage over other feasible alternatives is that it is largely immune to interference from nature—quakes, floods, droughts—economic vagaries and artificial accidents.

3. Low Coal: This scenario assumes a partial improvement in supply quality with imports in the same proportion as in FY ‘14-‘15, and pegs the requirement at 1,139 MT.

Source: Brookings India

Why are the targets too ambitious?

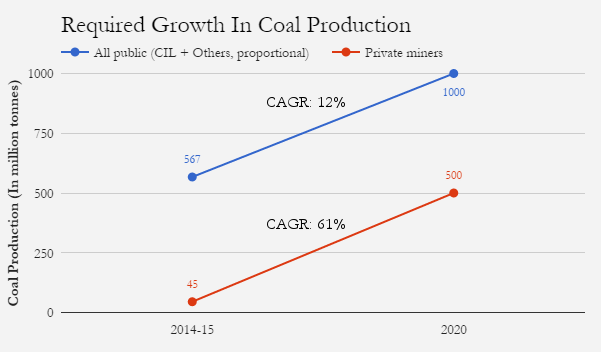

Today, about 45 MT of India’s coal production (7.4 per cent of coal production of India in FY ‘14-15) comes from private miners. Achieving the government target of 500 MT by 2020 would require an unprecedented 11 times growth or a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 61 per cent in the private sector.

If CIL and the other mining PSUs are to reach the 1-billion-tonne target, they will need to grow at an aggregated 12 per cent CAGR. If the growth target is limited to just CIL, then the company’s CAGR will stand at 15 per cent. The report notes that although CIL did achieve 8.5 per cent year-on-year growth in FY’15-16–its best ever–it still missed its target by 12 MT, settling for 538 MT in the last fiscal.

Source: Brookings India

The 12 per cent growth for CIL then seems unlikely, especially in the future over a larger base. A 12 per cent growth on a 500 base (production around 500 MT mark)–CIL produced 538 MT in 2015-16–is easier than on an 800 base (production around 800 MT), which means CIL must produce more than 800 million tonnes in the future.

Read the full article on IndiaSpend here.

Like other products of the Brookings Institution India Center, this report is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues. The views are those of the author(s). Brookings India does not have any institutional views.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edIndiaSpend article cites study on “India’s coal requirement by 2020”

IndiaSpend

September 8, 2016