Below is Chapter 4 of the 2026 Foresight Africa report, which brings together leading scholars and practitioners to illuminate how Africa can navigate the challenges of 2026 and chart a path toward inclusive, resilient, and self-determined growth.

Globally, democracy has been waning over the past two decades, marked by a rise of illiberal states, the deterioration of political and civil rights, and a fall in global voter turnout, according to multiple democracy tracking reports.1 African countries are no exception to this trend, even as democracy remains the preferred form of governance for most citizens and voter participation remains relatively high.2 Yet aggregate trends mask the significant divergences in democratic trajectories across the continent’s 54 countries.

Analyzing diverse democratization trends such as these was a major focus of the Africa Growth Initiative’s (AGI) project on the “State of democracy in Africa: Pathways toward resilience and transformation.”3 By looking at democratic resilience, which refers to “the ability to prevent substantial regression in the quality of democratic institutions and processes,”4 the project recognizes that democracy is not a linear process but a winding endeavor impacted by crisis events and windows of opportunity.

Democracy is not a linear process but a winding endeavor impacted by crisis events and windows of opportunity.

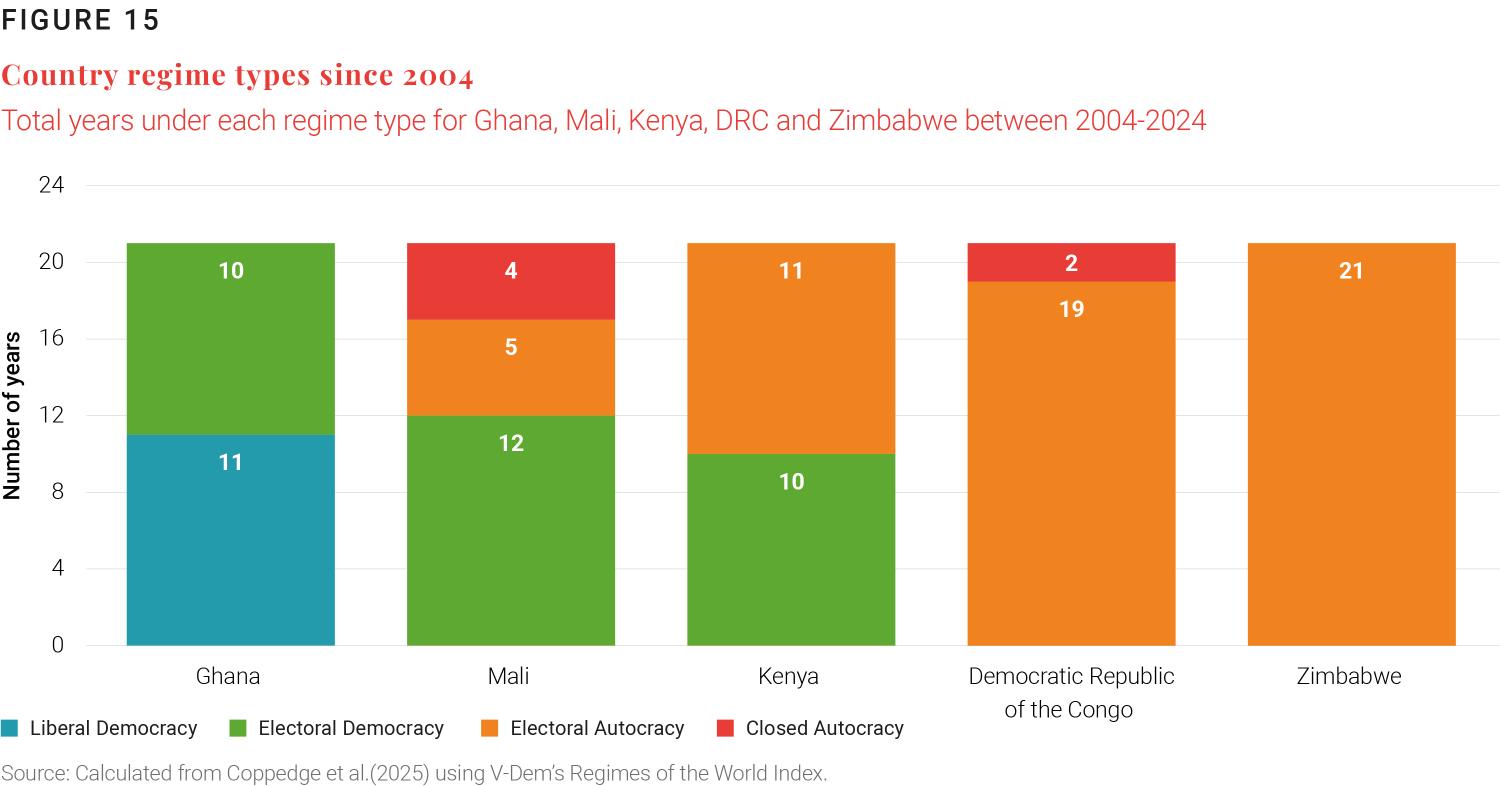

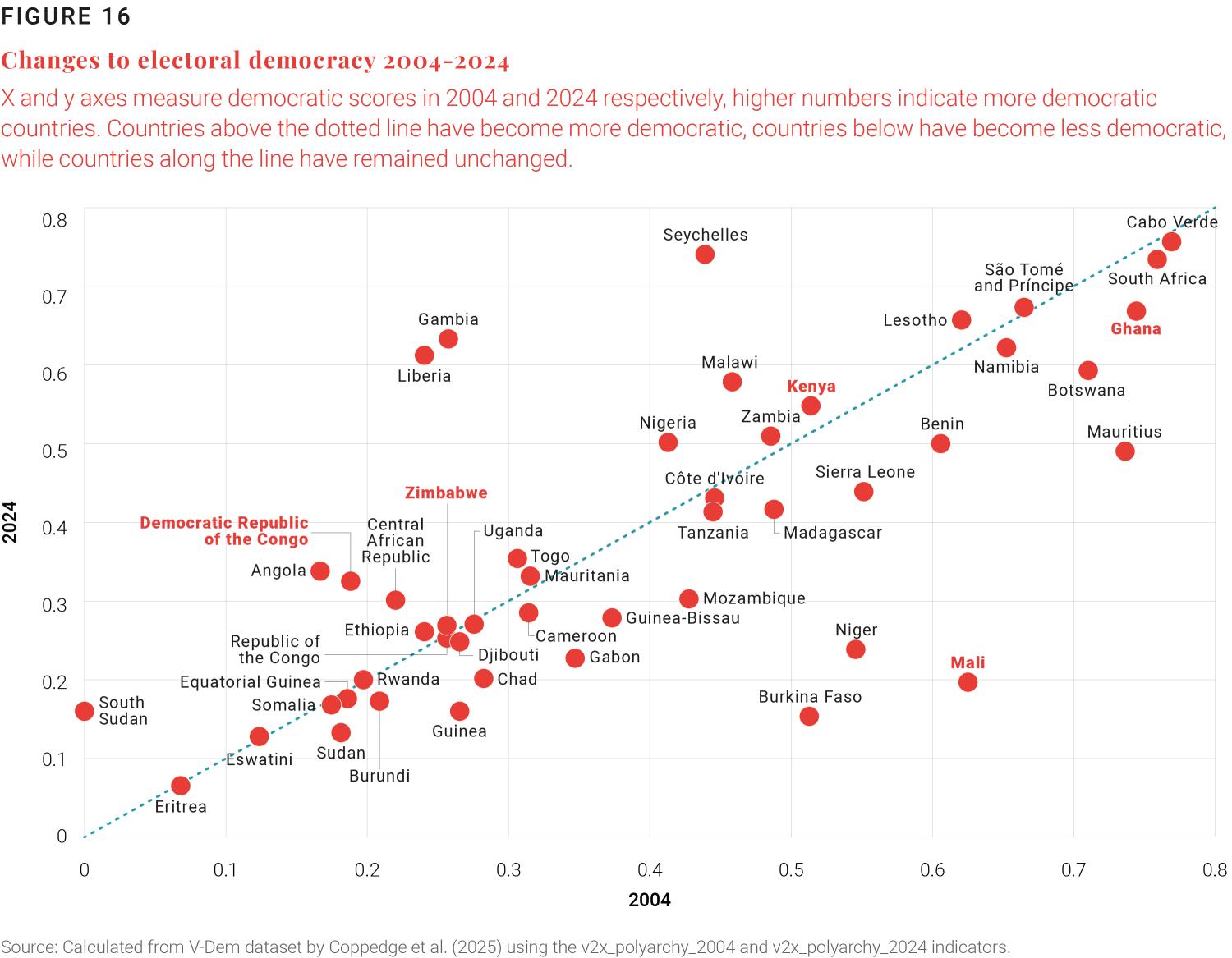

The project utilized in-depth case studies of five African countries at various ends of the spectrum of democracy: the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ghana, Kenya, Mali, and Zimbabwe. To provide more nuance about the trajectories in these countries, the project focused on three elements of accountability widely viewed by political scholars as essential for strong electoral democracies: vertical, horizontal, and diagonal accountability.5 Vertical accountability refers to the relationships between elites and citizens, often most clearly manifested through elections, while horizontal accountability encapsulates the ability of government oversight institutions, including the legislature, judiciary, audit bodies, and anti-corruption agencies, to exert checks and balances over the executive.6 Diagonal accountability refers to the ability of non-state actors, including the media, universities, and civil society organizations, to ensure state leaders and institutions stay responsive to their constituents. Democracies are most resilient when all three types of accountability are robust.

Ghana has remained strong on all three dimensions of accountability over the last two decades,7 while Zimbabwe has performed consistently poorly despite high hopes after Robert Mugabe’s ouster in 2017.8 Kenya has impressively bounced back since its extensive 2007 electoral violence,9 while Mali has dramatically reversed democratic gains due to four successive military coups since 2011.10 The DRC held elections in 2006 that were relatively free and fair—and has a relatively strong set of civil society actors—but has since experienced high levels of political volatility linked to a weak legislature, a proliferation of political parties with no clear policy agendas, and growing public mistrust of electoral processes.11 These diverse starting points and trajectories offered the basis for structured comparative findings about drivers of and barriers to democratic resilience.

Four key factors emerged as instrumental in these patterns.12 First, civil-military relations, which refer to the norms of engagement between civilian authorities and the military, impact accountability in crucial ways. If the military is given disproportionate decisionmaking power, then the security sector essentially becomes a parallel power structure that can interfere in elections, the bureaucracy, and civil society. By contrast, a professionally trained and apolitical military whose budget is overseen by civilians is key for ensuring peaceful transitions of power.13

Second, the underlying political economy—in terms of the sectors that drive economic growth and transformation— can impact elites’ access to resources, degree of corruption, and the level of inequality in a country. In turn, these factors impact citizens’ confidence and satisfaction with democratic processes, sometimes leading them to convey their grievances via protests rather than at the ballot box.14

Third, as echoed in research by Croissant and Lott,15 the nature of elite coalitions is pivotal, including whether power is widely distributed amongst many different groups or only narrowly so amongst a privileged coterie of insiders. In the latter scenario, elites may have more to lose when their party is out of power and therefore are more inclined to manipulate accountability mechanisms to avoid such an outcome.

Fourth, the makeup of party systems is determinative. Institutionalized party systems with historical or societal roots can better allow citizens to anticipate policy directions and structure elite expectations about the rules of the game than those party systems that revolve around an individual leader’s charisma and personal connections.16

If the military is given disproportionate decisionmaking power, then the security sector essentially becomes a parallel power structure that can interfere in elections, the bureaucracy, and civil society.

A second step of the project involved identifying feasible policy options to address democratic frailties identified in the country case studies. To enhance vertical accountability in Kenya, Otele, Kanyinga, and Mitullah (forthcoming) provide detailed prescriptions about how to improve Kenya’s campaign financing architecture. Such prescriptions include, for instance, reforming political finance rules to curb elite influence through stricter enforcement and stronger audit trail requirements of donations, enforcing campaign expenditure laws by establishing a monitoring unit for campaign finance law, forensic accounting and digital auditing, and strengthening financial oversight institutions with independent resources and personnel.

Likewise, Ofosu, Selormey, and Dome17 argue that a critical link in the vertical accountability relationship between voters and parties in Ghana are the grassroots party activists who often engage in vote buying and electoral violence on behalf of one of the country’s two main political parties. The authors argue this constituency—thus far overlooked by democracy assistance donors—could benefit heavily from civic education efforts to inculcate democratic norms.

In Mali, which has a long tradition of civic engagement processes, including national dialogues and conferences, Bleck and Soumano18 note that diagonal accountability could be enhanced by drawing on some of these indigenous practices. Namely, they advocate for the creation of citizens’ assemblies where randomly selected citizens deliberate on key issues facing the economy and their communities and then send their recommendations to the government. Civil society can lead by organizing dialogue and informing the government of their own resolutions, which governmental bodies could then adopt. Parliamentary restitution could be improved and deployed more often to give MPs direct interaction with diverse populations. To improve political party quality, the election management body can deliver civic education through creative outlets like local radio, and the government can sponsor deliberative forums with civil society representatives and traditional and religious leaders, moderated by journalists.

In Zimbabwe, Dendere (forthcoming) argues for expanded foreign investments in civil society groups that support human rights and fight corruption as well as broader engagement of the international community with the current government on trade issues that might concurrently incentivize the regime to embrace further governance reforms.

Finally, in the DRC, Stearns, Batumike, and Bauma (forthcoming) offer many suggestions for enhancing horizontal accountability; these include tackling the civilian-military imbalance by, among other tactics, eliminating discretionary benefits to the military that foster politicization and allowing for an independent investigation into army finances.

As another group of countries with wildly different democratic trajectories head to the polls in 2026, including Cape Verde, Benin, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Zambia, the key findings from the AGI project about drivers of resilience can be more broadly tested. And, with the dramatic reduction in foreign aid for democracy assistance in 202519—a trend likely to continue in the years to come— the project offers practitioners insights into the types of interventions that could be prioritized in contexts of resource scarcity.

Related viewpoints

-

Footnotes

- Anna Juhola, “Two Decades of Decline in the Global State of Democracy,” Demo Finland, April 9, 2025.

- Afrobarometer, African Insights 2025: Citizen Engagement, Citizen Power: Africans Claim the Promise of Democracy (Afrobarometer, 2025).

- Details from the project can be found at: https://www.brookings.edu/collection/the-state-of-democracy-in-africa/

- Vanessa A. Boese et al., “How Democracies Prevail: Democratic Resilience as a Two-Stage Process,” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 886.

- Anna Lührmann et al., “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability,” American Political Science Review 114, no. 3 (2020): 811–20,; Guillermo O’Donnell, “Horizontal Accountability in New Democracies,” Journal of Democracy 9, no. 3 (1998): 112–26; Landry Signé, Accountable Leadership: The Key to Africa’s Successful Transformation, Global Views no. 9 (The Brookings Institution, 2018).

- Landry Signé, “Executive Power and Horizontal Accountability,” in Routledge Handbook of Democratization in Africa, First (Routledge, 2019); Landry Signé and Koiffi Korha, “Horizontal Accountability and the Challenges for Democratic Consolidation in Africa: Evidence from Liberia,” Democratization 23, no. 7 (2016): 1254–71.

- George Ofosu et al., Ghana’s Democracy under the Fourth Republic (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Miles Tendi and Chipo Dendere, Understanding the Evolution and State of Democracy in Africa: The Zimbabwe Case Study (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Oscar Otele et al., Kenya’s Resilient Democracy (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Jaimie Bleck and Moumouni Soumano, Explaining Mali’s Democratic Breakdown: Weak Institutions, Extra-Institutional Alternatives, and Insecurity as a Trigger (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Ithiel Batumike et al., DRC: An Oligarchic Democracy (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Danielle Resnick and Landry Signé, Prospects for Democratic Resilience in Africa During Uncertain Times (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Louis-Alexandre Berg, “Civil–Military Relations and Civil War Recurrence: Security Forces in Postwar Politics,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, nos. 7–8 (2020): 1307–34.

- Monika Bauhr and Nicholas Charron, “Insider or Outsider? Grand Corruption and Electoral Accountability,” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 4 (2018): 415– 46; Eliska Drapalova et al., Corruption and the Crisis of Democracy: The Link between Corruption and the Weakening of Democratic Institutions (Transparency International, 2019).

- Aurel Croissant and Lars Lott, “Democratic Resilience in the Twenty-First Century: Search for an Analytical Framework and Explorative Analysis,” Political Studies, SAGE Publications Ltd, June 28, 2025, 00323217251345779.

- Noam Lupu and Rachel Beatty Riedl, “Political Parties and Uncertainty in Developing Democracies,” t46, no. 11 (2013): 1339–65; Gideon Rahat, “Party Types in the Age of Personalized Politics,” Perspectives on Politics 22, no. 1 (2024): 213–28.

- George Ofosu et al, Shaping Democracy from the Middle: Party Grassroots and Ghana’s Democratic Progress (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Jaimie Bleck and Moumouni Soumano, Consultations in Mali: Drawing on democratic heritage to deepen democratic practice (Brookings Institution, 2025).

- Annika Silva-Leander et al., When Aid Fades: Impacts and Pathways for the Global Democracy Ecosystem (Global Democracy Coalition, 2025).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).