Another football season has started in Europe, including the prestigious Champions League. Some of the teams’ key protagonists—Messi, Ronaldo, and Schweinsteiger—are all playing away from their home countries. They are economic emigrants.

The refugees who have entered Europe in recent weeks are less fortunate. In recent posts Future Development has covered many facets of the ongoing crisis with refugee, most of whom fled their countries from war and persecution. Many refugees might still stay for a long period, and thus become migrants. This is why I would like to reflect on the long-term economic impacts of migration on Germany. Football is a great illustration because clubs are full of migrants and their economic and social role has increased dramatically, making the sport a $29 billion business in Europe (2014), not counting all the indirect economic spillovers.

In 2015, my home country Germany may welcome up to 1 million refugees. We have been there before. The news footage of refugees in the Budapest train station chanting “Germany, Germany” reminded many of my compatriots not only of football stadiums but also of the events which, a quarter of a century ago, paved the way for Germany’s reunification and the end of the cold war: when East German refugees fled to the West across Hungary. Then as now, after an initial emotional response came tough questions: will these new migrants eventually help our countries or overburden our economies?

If we take the example of football it should be clear that immigrants have not been overburdening us, even though some might argue that foreign players are taking away jobs from German-born footballers. My home club Bayern Munich, which is run by a Spanish coach, is an interesting case. The typical line-up of the team this season saw only four (sometimes five) German players on the pitch, including Jerome Boateng, whose father is from Ghana; the other seven players come from many different parts of the world.

Imagine we expanded the same approach to the whole economy: filling seven or eight positions out of eleven by migrants. Would this not create mass unemployment? I would argue no, in fact the opposite, for two key reasons.

First, the football business is a perfect illustration of the “lump of labor fallacy.” Many politicians often assume that the key parameters of an economy are fixed so that when migrants come, they necessarily take jobs away from natives. This thinking is wrong because immigrants who work also contribute to growing the “cake” and the overall pool of employment opportunities. German football players are also benefitting from the internationalization of their business because they earn much higher salaries today at all levels. Today, salaries of football players in Germany and other parts of Europe are about four times higher in second league than they were in the first league in the 1990s. The football cake grew in a major way when it became a global entertainment business with many customers all over the world. This has created many jobs on and off the pitch for native Germans and immigrants alike.

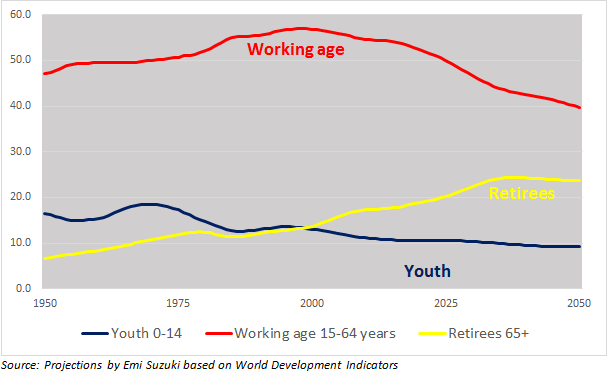

Second, for Germany to remain competitive, not just in football, it needs talented people. Since 2005, we are on a path of demographic decline, with some dramatic consequences in some rural areas, where local governments started to close down public services. In lower Saxony, a mayor recently announced that new residents would be offered plots for free if they moved into his town. Without immigration, the country’s workforce will shrink from 54 million today to an estimated 40 million by 2050 (see Figure 1) and already by 2030, Germany will face a workforce crisis. Everything else being equal, Germany would need an inflow of 370,000 working immigrants per year to close this gap.

Figure 1. Germany’s demographic decline (without migration)

Football in Europe is also a reflection of the global demographic divide. There are many young and fast growing countries in the South that face the opposite challenges of the aging and shrinking countries in the North. Temporary labor migration as well as permanent relocation can be part of a global solution to bridge this divide. Some countries, such as Australia, Canada, the U.K., and the U.S. have been relatively successful in attracting global immigrants and integrating them into their societies. These experiences hold important lessons for other high-income countries, and increasingly middle-income countries, which are struggling to embrace the potential of immigration despite the fact that they already have stagnating populations.

Integration of immigrants will be a big challenge for Germany and other European countries, but by no means a new one. After the Second World War, Germany did a remarkable job in integrating 12 million refugees—including my father—from its previous Eastern territories, and few would argue that it was unsuccessful in meeting one of the greatest integration challenges ever. People have always moved and yet how easy it is to forget that our ancestors have been migrants as well. Watching a game of football can be a good reminder.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

If you like football, you should welcome migrants

September 24, 2015