Following Shanta’s confession of his past professional sin in costing the MDGs, it is now my turn to share my experience with a fundamentally flawed belief.

In my youth and up until the 1990s I still thought, like most activists on the left did, that the solution to global poverty lay in taking resources away from the rich and redistributing them to the poor. At that time the world had a relatively stable structure with the so-called first world (market-based rich countries), second world (the socialist countries), and third world (the remaining countries, almost all of them very poor). Fighting inequality and injustice was seen as the same as redistribution. It was and still is a very human approach to many of the ills that are still affecting us across the world. People who care about others want to fight the injustices of the world.

At the global level, we believed in the “dependency theory,” which assumes that rich countries acquired their wealth through “exploitation” of poor countries. It is true that there has been exploitation of dramatic scales in history; even today, many tragedies are related to global inequality (just look at all those stranded and dying in the Mediterranean). However, the fact that Northern countries are rich because Southern countries are poor is misguided. I still remember the moment when my professor called these beliefs “pure nonsense.” I shuddered because I felt that this was an outrageous statement. It took a while until I grasped that countries like the East Asian Tigers and many other emerging economies grew rich despite their alleged dependency on the West.

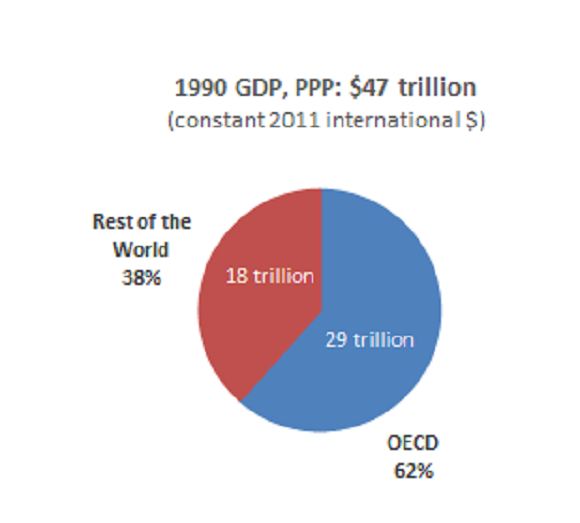

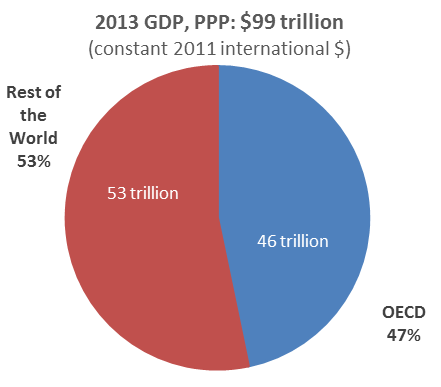

Too often we follow a “fixed-cake” fallacy. The main mistake many people make, and I was among them, is to assume that the economic cake is fixed in size and things will stay as they are today. If that were true, it would be even more challenging to fight poverty and injustice because many people would need to reduce their standard of living for others to gain something. Fortunately, the cake does grow. Since 1990, global GDP has more than doubled from $47 trillion to 99 trillion (PPP, 2011 Int$). Most of this growth has happened in countries that were as poor 25 years ago as most of Africa is today. Today’s GDP of emerging markets and developing countries is larger than the total GDP of the world in 1990 (see Figure 1). If the world only focused on redistribution, many of these previously poor countries could have never grown rich.

Figure 1: The cake doubled since 1990, mainly thanks to emerging economies

So how did countries like South Korea, Chile, and India overcome the dependency they were said to be in? Instead of pursuing protectionist trade and economic policies as suggested by dependency theorists, these economies opened themselves up to foreign trade and supported export-oriented production. Other countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, are still trying to catch-up. But they are left behind because of too little—not too much—trade. If sub-Saharan Africa suddenly ceased to exist there would be little impact on a country like Germany, whose trade with the region is now at around 1 percent and only starting to pick up gradually. If there were more trade, poor countries would likely be much wealthier.

Catching-up is easier if every person can develop their full potential, if there is equality of opportunity. Joseph Stiglitz’s recent argument that rising inequality in societies hampers development, especially if incompetent people reach power and maintain it at the detriment of the poor, is a prescient warning of the dangers of inequality. At the same time, this is should not be mistaken with the fact that some degree of inequality is a natural consequence of development. Just imagine life some 10,000 years ago. With very few exceptions, everyone would have been considered poor by today’s definition. As many people get richer, the gap between those escaping poverty and those left behind is naturally getting larger, a trend we observe even as a larger share of people escape poverty.

In short: Whenever you listen to politicians, watch out if they want you to believe in the fixed cake fallacy. Instead, think of development as a dynamic process. Think of young people not just as those in need of jobs, but also those creating jobs. Think of an interconnected knowledge world, where what you have in your brain and heart matters more than what you have in your pockets. Then you won’t make the same intellectual mistakes I made.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The fixed cake fallacy: Why I was wrong to believe that rich countries are rich because poor countries are poor

May 1, 2015