After nearly 80 years of war, Colombia is on the cusp of closing a historic peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC), the country’s largest guerrilla group. The parties have set a March 23, 2016 deadline to conclude talks. Drug cultivation and trafficking are crucial aspects of the deal, as drug profits have long enabled the country’s violent conflict.

In a major breakthrough, the Colombian government and the FARC have agreed on a joint counternarcotics strategy. As it should be, developing alternative livelihoods—couched within a larger rural development plan—is core to the policy.

What would a peace deal between the Colombian government and the FARC mean for drug production and routes? Production won’t disappear from the country any time soon, but sustained efforts to improve rural livelihoods can pull Colombians away from coca production in the long run, while well-designed interdiction can reduce some of the harms, including violence, associated with drug trafficking.

Peace with drugs after all

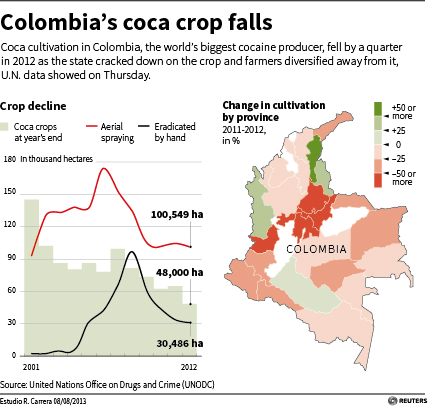

In spring 2015, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos suspended the controversial aerial spraying of coca fields due to harmful health effects. This ended what had been the cornerstone of Colombia’s drug policy and U.S. assistance in the country for years. Along with the FARC peace deal, this is a major reversal of Colombia’s basic strategy toward drugs and conflict (though the government has not ruled out all means of eradication, including forced eradication, for counternarcotics purposes).

Colombian police planes spray herbicide on a coca plantation in San Miguel, Putumayo province, 2006. Credit: Reuters.

For years, the Colombian government insisted that drugs had to be eradicated in Colombia before the conflict could end. The United States has spent almost $10 billion in combined counternarcotics and counterinsurgency assistance to the country since 2000.

But forced eradication campaigns, including aerial spraying, often just drove cocaleros (small cocaine growers) into the FARC’s arms. The campaigns also failed to bankrupt the FARC, though interdiction occasionally dented the funding of particular FARC columns. It expanded its illicit economic activities into illegal mining and logging, as did its leftist guerrilla and rightist paramilitary rivals.

Colombia has finally accepted what many other countries already knew: that conflicts can end even while insurgents make illicit profits. Other countries, such as Peru, Thailand, Burma, China, Northern Ireland, Lebanon, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Nigeria, to list just a few, were able to end conflict without ever eliminating or even substantially reducing the illicit economy.

The right sequencing

In fact, ending violent conflict is a precondition for eliminating an illicit economy, not the other way around. Reducing the illicit economy requires good government access and sufficient security. That can be achieved either through mailed-fist repression (in the case of Burma in the 2000s or China in the 1950s) or through developing alternative economic opportunities, as Thailand has done. Thailand is the most successful alternative livelihoods case ever, in fact, and Bolivia’s uno cato policy could be a good model for Colombia as well.

The “eradication first, alternative livelihoods second” approach has never worked in Colombia, even with the best of intentions. Colombian officials should resist continuing to embrace such counterproductive policies.

Drugs there will not disappear just because the FARC signs a deal.

Tolerating some coca cultivation will be necessary and will actually enable the development of alternative livelihoods. It takes several years, after all, for legal production to start generating much income. And some areas are simply too remote for any legal agricultural project to be profitable. In those areas, coca will persist—the only solution is to attract people to move. Given Colombia’s history of brutal internal displacement and land theft, it will be crucial to ensure that such relocations are truly voluntary.

The history of alternative livelihoods, including programs such as Guardabosques to eliminate coca cultivation in national parks, also shows its share of failures. This is often due to sequencing problems, with officials putting eradication before alternative livelihoods are sufficiently in place. Another policy mistake includes over-focus on shifting to a replacement crop, such as coffee or cacao, and under-focus on development-support infrastructure and value-added chains. Developing off-farm job opportunities and investing in cocaleros’ (or potential cocaleros) basic human development is also essential. None of this is easy, but the evidence shows that these problems can be fixed. In contrast, eradication programs without alternative livelihoods in place already, not merely promised in the future, will always be problematic in Colombia.

New buyers and sellers

Drugs there will not disappear just because the FARC signs a deal. Some FARC frentes (units) may persist in sponsoring cultivation and trade in cocaine, perhaps even breaking off from the rest of the group.

Moreover, plenty of other drug-trafficking sponsors are available: the other main leftist group, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN)—with which peace negotiations have not taken off—as well as Mexican drug trafficking groups operating in Colombia or new Colombian groups.

Coca cultivation and cocaine production in Colombia has fluctuated over the years. After dominating the world’s production for almost 20 years, Colombia yielded the first-place slot to Peru in 2013.

But in 2014, Colombian coca and cocaine production swung back up, again outpacing Peru and Bolivia (the world’s No. 2 and No. 3) combined.

The U.S. and Colombian governments have blamed the upswing on the FARC, saying they have encouraged cocaleros to grow more coca. But that’s too simplistic. The cocaleros are far from FARC pawns—to the contrary, they have become more politically organized in their own right. This reinforced the FARC’s decision to negotiate, as it became obvious that the group could no longer count on its original core support base.

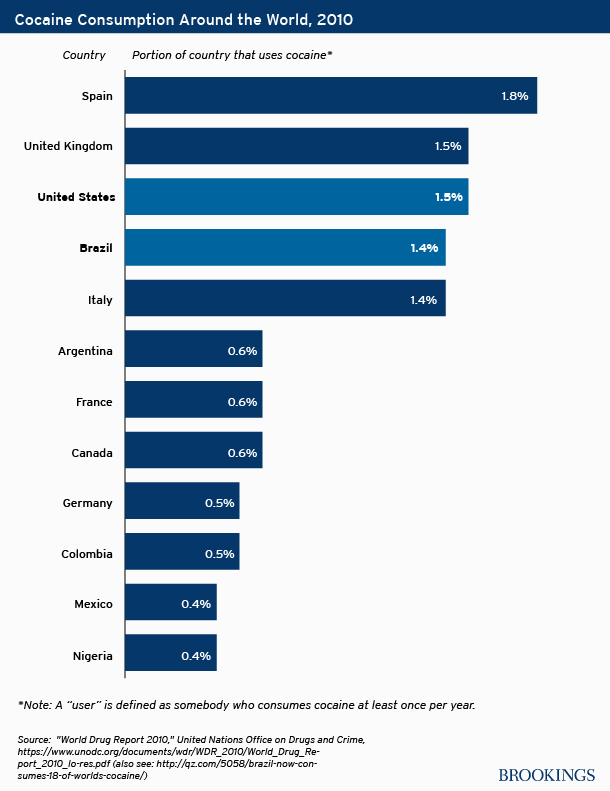

More fundamental market forces are also at play. Demand for cocaine has been declining in the United States—but it has risen in Europe (smuggled through West Africa), Brazil, Argentina, and China. Although Brazil and Argentina have been loath to disclose consumption data, the internal per capita demand in both countries is widely believed to be on par with the United States. Much of the Brazilian and Argentinian demand is supplied by cocaine from Peru and Bolivia, but much more can be supplied from Colombia. Eventually, however, Colombia could face new production competitors, as coca cultivation could increase in Ecuador and Venezuela. So even if coca production is reduced in Colombia, it will rise somewhere else.

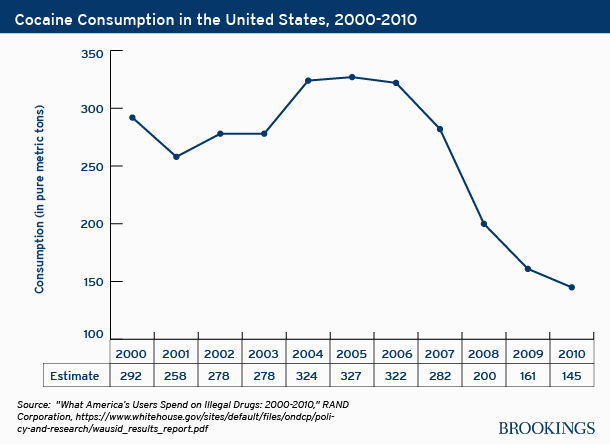

Cocaine consumption in the United States has fallen dramatically since 2006.

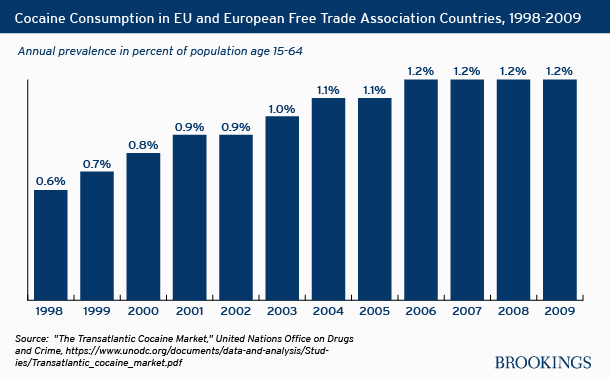

Cocaine consumption in Europe has been steadily rising.

Cocaine use in Brazil is nearly on par, as a portion of population, with the United States.

In it for the long haul?

It’s not clear that the Colombian state and elite can or will sustain the flow of resources necessary to develop areas that have legal economic potential. Under far more auspicious circumstances, eliminating poppy cultivation in Thailand took 30 years of alternative livelihoods efforts (and methamphetamine production and other illicit economies still persist). But, coupled with smart interdiction to reduce violence in Colombia’s drug markets, it’s still the country’s best option for dealing with its drug problems.

The Colombian government will need to confront those vested interests opposed to more equitable rural development. Disappointingly, it hasn’t even been able to generate the resources for a flagship post-counterinsurgency rural development program in Macarena (a small territory in comparison with the overall need in Colombia), having to rely on U.S. funding and ultimately downsizing the program.

Rural development in Colombia won’t be easy: It will require a lot of resources, time, and political wherewithal. But that is the only path to reducing coca cultivation in Colombia that is politically sustainable and consistent with human rights principles.

The core challenge is that rural development in Colombia will demand larger changes in the country’s economic and political power arrangements, enabling far greater inclusiveness and equity. Among these is the highly sensitive and demanding task of changing a taxation system: Currently land is taxed very little, encouraging land theft and concentration (including for money laundering), as well as letting land lie fallow. On the other hand, labor is taxed heavily, encouraging capital-intensive growth instead of the much-needed legal job creation.

Without far greater inclusiveness, Colombia won’t be rid of drugs and illegality, nor will its peace be fully satisfactory.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How to break free of the drugs-conflict nexus in Colombia

December 16, 2015