The federal government is reconsidering how the census collects race and ethnicity information from U.S. residents. While this might not capture many national headlines, it is an important process that many social science researchers—including education researchers—are paying close attention to. This is because decisions over how we collect race/ethnicity data are both highly consequential and inherently subjective. These decisions have direct implications for the allocation of public resources and shape how we understand what is happening in U.S. schools and society. Yet, there is no “correct” set of racial and ethnic categories, which leaves a wide range of outcomes for these decision-making processes.

In this piece, I describe how the process for identifying race/ethnicity categories works, why it matters, and what I believe the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should ultimately recommend to the U.S. Census Bureau to ensure that this revision process is a success.

The federal government takes another look at racial/ethnic categories

Race and ethnicity are sociopolitical constructs, with categories that are not natural, neutral, given, or static. As such, the process of choosing categories should mirror how we as individuals and as a society change over time. However, OMB and the U.S. Census Bureau have only occasionally taken up the issue (i.e., in 1977 and 1997). As a result, the current categories are outdated and not reflective of our diverse multiracial society.

How the census collects race/ethnicity data sets the precedent for all state and local agencies to follow. School districts, for example, are required by the U.S. Department of Education to collect race data using categories that closely align with those used in the census: Hispanic, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, white, and two or more races. In education, the decision to use these broad racial categories limits our ability to identify unmet needs, ensure services are accessible to all racial/ethnic groups, improve access to services, and advocate for an adequate and fair distribution of resources and funding. Although agencies can take initiative and gather their own more nuanced racial/ethnic data—as the Portland Public Schools and Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction have done—these agencies have been the exception, not the norm.

As a first step, OMB convened a Federal Interagency Technical Working Group on Race and Ethnicity Standards, consisting of 14 principal statistical agencies and 25 other federal agencies. It held virtual public listening sessions beginning in late 2022 (which I participated in). Those conversations informed the Working Group’s suggestions for how the census should revamp its collection of race/ethnicity data. The Working Group has suggested changes that are aligned with our changing society. For example, they proposed eliminating the use of the terms “majority” and “minority,” removing “Negro” from the Black or African American description, replacing “Far East” with “East Asian,” and removing “Other” from “Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander.”

What’s missing from OMB’s race/ethnicity data collection recommendations

I support OMB’s recommendations. If these changes are implemented, they would create a new status quo in how government agencies approach racial/ethnic data collection. I also have thoughts on how we could further improve our processes for collecting these data:

First, race and ethnicity should be merged into one question allowing individuals to mark all that apply: “What is your race or ethnicity?” The status quo—with separate questions about race and ethnicity—results in an estimated undercount of Latinos by five percent and overcounting of white individuals. This is especially concerning for school districts or state departments of education using this approach, given that Latinos represent 14.1 million K-12 students (or 28% of the public school population). A five percent undercount translates to hundreds of thousands of students potentially being misidentified. It’s important to note that two-thirds of Latinos consider “Latino” to be their race. Despite the fact that concepts of ethnicity and race are sometimes conflated, ethnicity is not the same as race, as it encompasses multiple dimensions, including language, culture, religion, and nationality. Since Latino is not an option for the race question, many feel forced to select “white” even if they do not identify this way and are not offered the privileges of being white in America. For Afro-Latinos, who constitute 12% of the Latino population, having separate questions has allowed them to mark Latino as their ethnicity and Black as their racial identity. The merge option would still allow them to mark both.

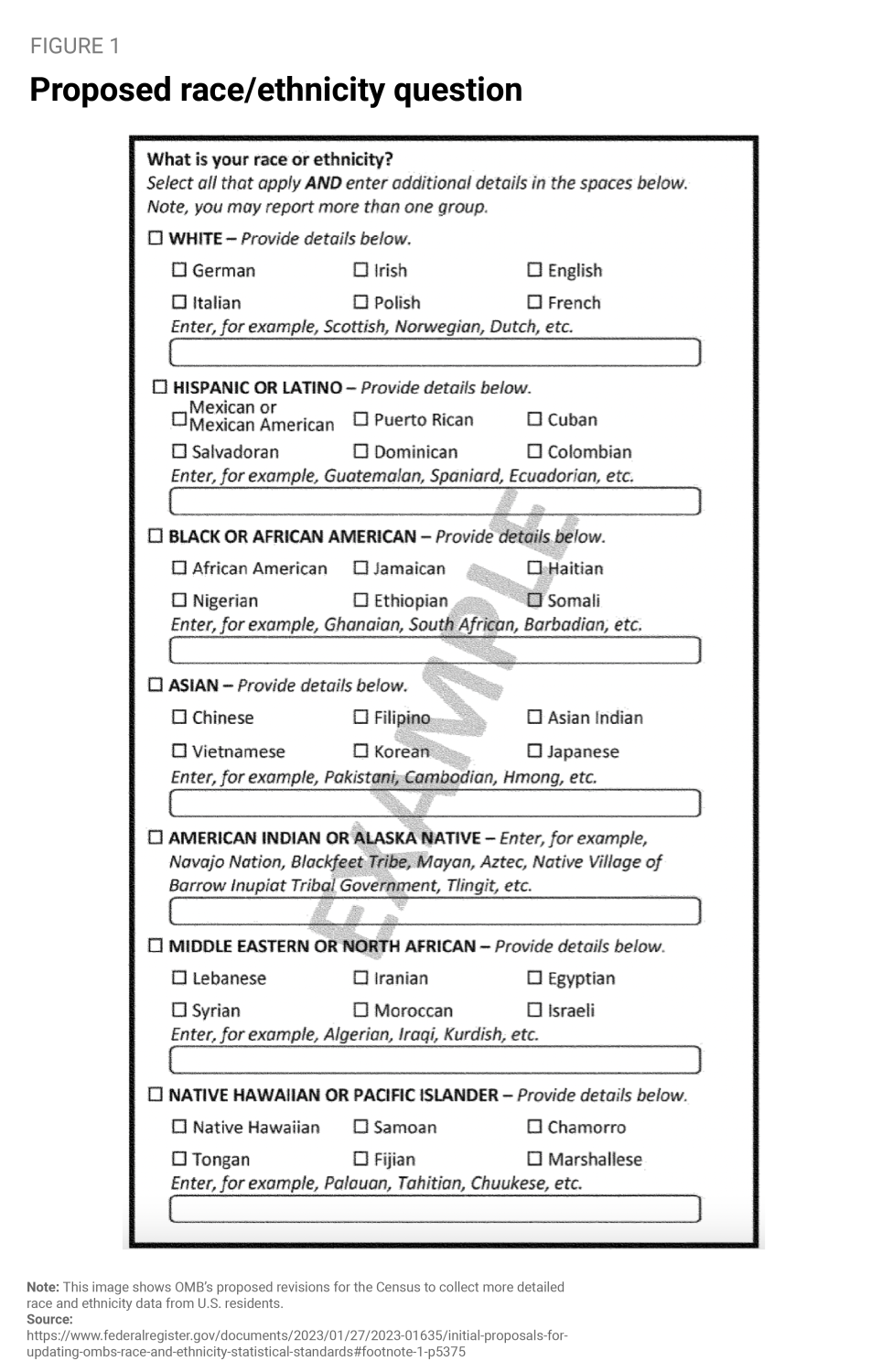

Second, the federal government should also consider collecting disaggregated race/ethnicity data. This would mean adding follow-up questions to the merged race/ethnicity question to allow respondents to provide more detailed data on how they self-identify. That is, after asking a merged race/ethnicity question, a follow-up question with additional subcategories would appear. The OMB working group has already proposed something along these lines—suggesting that the census also collect information on countries of origin as subcategories for each racial group (See Figure 1 below).

Collecting disaggregated data upfront would allow analysts to use aggregated data, if needed, but also examine subcategories to identity patterns or needs that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. For example, the Asian community is often treated as a monolith, but when examined further, Southeast Asians are dropping out from high school at higher rates and enrolling in college at lower rates compared to South and East Asians. The same data also defies the myth that Latinos are one big group, similarly, showing Central American students dropping out of high school at higher rates and enrolling in college at lower rates compared to other Latino subgroups. Our awareness of, and response to, these patterns require a nuanced understanding of them.

A potential approach to pilot would add an additional layer by asking for subcategories by region first, followed by specific countries of origin. For analysts and researchers disaggregating data, this option may prove useful since sample sizes may become too small for any meaningful disaggregation by country. For example, after selecting “Latinos,” there could be a drop-down list that could include the following subcategories: Puerto Rican, Mexican, Central American, Caribbean American, South American, Spanish, and/or Afro-Latino, followed by subgroup questions of countries of origin. Adding the Afro-Latino option under the Latino and Black subcategory is important to ensure that individuals who are Latino are still prompted to elect their Black identity (a concern expressed in the OMB listening sessions).

Third, for collecting data on Indigenous peoples, the options in the census form in Figure 1 should be guided by direct consultations with Native nations. The U.S. government has not collected Indigenous data accurately for centuries, leading to undercounting Native people and a way of seeing Indigenous communities through a deficit lens (e.g., using “Indian” until 1950). Here, it is important to note that the census relies on individuals’ self-identification of their racial and ethnic identities, whereas Native nations rely on tribe membership. Put another way, as Native writers have stressed, Native American is not a racial identity but rather a political one. This fundamental difference in identification has led to inaccurate data collection, undercounting, and potentially a masking of inequities.

Advocates and scholars argue for the decolonization of Indigenous data by repositioning the authority back to Indigenous peoples. In education, this means directing resources, data infrastructure, and investment in personnel capacity to tribally controlled schools and to the Bureau of Indian Education to give Native nations Indigenous data sovereignty–the right for each U.S. Native tribe to collect, own, and use its own tribe’s data.

By following these proposed changes, the federal government will set a model for other local government agencies to follow, and lead in a more accurate, nuanced, and respectful collection of data on race and ethnicity. Rather than convening every 30 or so years, OMB and the U.S. Census Bureau should have a standing working group to regularly gather feedback from communities to continuously improve data collection. These efforts will help us understand the inequities in our society, identify solutions to remedy these inequities, and make changes in our policies and institutions to address the effects of systemic racism. While thoughtful data collection is not sufficient for these pursuits, it is certainly necessary—and long overdue.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How students can benefit if the federal government collects richer race and ethnicity data

August 28, 2023