I want young people to see this as a place they're called to come or called to return to and not forced to stay.

Luke Glaser

Hazard, Kentucky, is overcoming the decline of its coal industry and the impact of the opioid epidemic, creating a vibrant downtown business district and renewed civic spirit. In this episode, Tony Pipa visits the Queen City of the Mountains to meet the people who decided downtown was worth fighting for and understand how they brought it back to life.

Featuring:

- Kennedy Caudill, Civic Fellow, City of Hazard

- Stacie Fugate, Director, InVision Hazard

- Luke Glaser, Assistant Principal, Hazard High School; City Commissioner

- Donald “Happy” Mobelini, Mayor, City of Hazard

- Moriah Musick, Civic Fellow, City of Hazard

- Kailey Pennington, Civic Fellow, City of Hazard

- Maggie Prosser, Co-owner, Hazard Coffee Company

- Stephen Prosser, Co-owner, Hazard Coffee Company

- Bailey Richards, Downtown Coordinator (former), City of Hazard

- Mandi Fugate Sheffel, Owner, Read Spotted Newt bookstore; Project Coordinator, Sycamore Fund, Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky

Want to learn more? Dive deeper into Hazard, Kentucky’s story of renewal in Tony’s interview with Ryan Eller. He shares his insights on how the community is creating a new identity, shifting the narrative around rural America, and charting a path for a future that moves beyond its coal-centric history.

Transcript

CAUDILL: It doesn’t matter in Hazard what you look like, what you do like. There’s always a seat at the table and we wanna listen to you. ‘Cause Hazard is weird. We are full weirdness. We are the odd cats of Appalachia, and we want to hear whatever anybody has to say.

[music]

PIPA: The “odd cats of Appalachia”—it’s not your typical city branding. And honestly, it might be a tricky moniker for a town in Eastern Kentucky given the stereotypes about the region. This is a place that was hit hard by the decline in the coal industry and by the opioid epidemic.

But for Kennedy Caudill, the “odd cats of Appalachia” captures the spirit of openness, quirkiness, and civic creativity that is helping revive his hometown of Hazard, Kentucky. He’s a biology major a couple of hours away at Eastern Kentucky University, preparing to become a science teacher after he graduates. But—and this may be a little unusual for a college kid—he’s also really interested in local government.

Kennedy spent the summer of 2025 working for the city of Hazard as one of three Civic Fellows, a program that has staked its claim as “The Most Comprehensive City Internship in the State of Kentucky.” It’s just one of several things that makes Hazard stand out among small towns in the coalfields of Central Appalachia.

[music]

I’m Tony Pipa, a senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution. And this is Reimagine Rural, the podcast where I talk to local people, capture their stories of the positive changes unfolding in their hometowns, and explore the implications and the intersections with public policy. In today’s episode, we’ll visit Hazard, Kentucky, known as Queen City of the Mountains, to learn how a cadre of new leaders, creative civic collaboration, and a willingness to take risks has revitalized the heart of downtown Hazard.

[archival tape]

Hi, this is Dolly Parton, and I’d like to remind all of you that I’ll be in Hazard, Kentucky on October the 11th — that’s on a Saturday — for the King Coal celebration. We have a lot of country music going on, and I’d like to invite you to come out and be part of it with us. I’ll be there along with all my traveling family band, and I look forward to seeing you. Okay? See you then.

PIPA: Hazard is a mountain town bisected by the north fork of the Kentucky River, about two hours southeast of Lexington, and an hour west from the Virginia border. A century ago, more than 40 coal companies operated here within a 10-mile radius. And at one time, there were five hardware stores on Main Street. So having a popular musical act like Dolly Parton, who came through town in 1975, was normal.

But like so many small towns across Central Appalachia, Hazard saw its thriving downtown diminish alongside the decline of the coal industry and the effects of the opioid crisis.

[music]

A little over a decade ago, Hazard had a run of bad news that just didn’t seem to let up. In 2013, two people died and a teenager was injured in a shooting in the parking lot of the community college campus in town. In 2014, the New York Times published a disparaging article entitled “What’s the Matter With Eastern Kentucky?” complete with an illustration of a Kentucky vanity license plate spelling out “HELP ME” in capital letters. It was a companion piece to an analysis about the so-called hardest places to live in the United States. A scene from Hazard was the featured photo.

[3:52]

GLASER: I think that was, like, the low point of downtown was 2015.

PIPA: That’s Luke Glaser, a town council member and assistant principal at Hazard High School, where he’s also a teacher. Luke created the Civic Fellows program in 2019. We’ll come back to that a little later.

GLASER: There was a group around that same time that got organized called InVision Hazard. It was just a community action board. It was just a bunch of people who were invested in making downtown a thing again. And it started with small things like an event, a float in the annual parade. And I think one of the big things they did, they did a party on top of the parking structure downtown for Hazard’s birthday. And that was a big festival and a big thing. And, like, you can come downtown and it’s safe and everybody has a good time.

PIPA: Around that time, Luke was teaching math at Hazard High School. And he set aside a full pre-calculus class period each week and called it “Calculus Creates Problem Solvers.” If it seems to some like he was shoehorning a civic lesson into a math class, for Stacie Fugate, who was 16 at the time, it was a revelation.

[4:55]

FUGATE: And so one of his biggest things to tackle was that you can make kids learn math all day long, but you can’t necessarily make them care about it. And he started off by showing us all of these stereotypes that the outside world thought about Appalachians and thought about Eastern Kentuckians. So I remember just being so angered that people thought this of us, all across the United States, no matter what you put us up against, right? we’re a very resilient group of people. We’re very intelligent and we’ve always had to be because the rest of the country isn’t coming to save us. Right?

So I remember seeing these stereotypes and really for the first time I started thinking about systemic issues and why why people thought that of us, you know, I started doing my research on the history of these stereotypes. And so it didn’t just end with Luke telling us and showing us all of this media. It ended with, let’s find a problem in our community that we can solve.

PIPA: Stacie and some other kids from Hazard High School started joining Luke and others at those InVision Hazard meetings.

[6:00]

FUGATE: I felt overwhelmed because there was stuff that I didn’t know, but I also felt very welcomed, because there has always been people in positions of supervision, for me at least, and in higher up positions and leadership positions that have made me feel welcome and made me feel like my ideas matter, especially as a young person in this town.

There’s this four year period where InVision Hazard we were doing public facing events. You know, we were doing Thursdays on the Triangle, we were throwing Founder’s Days parties in the parking structure and bringing life in the form of events back to downtown. And so I think that did a little bit of narrative change work, a little bit of that hearts and minds work, where people see stuff happening in downtown and they’re like, oh!

[music]

That doesn’t sound like much, but to a town where there hasn’t been a ton of livelihood, seeing a parking structure party with the string lights and with live music and just something to do, giving people something to do. That does more work and does a lot of heavy lifting for the hearts and minds work that we needed to do in order to get Bailey hired and make her be able to be successful in her position.

PIPA: Stacie eventually graduated from high school, went to college, and now she’s back in Hazard working as InVision’s director. But back in 2018, when she was a high schooler, the group didn’t have a budget, or staffers, or nonprofit status. They did have solid ideas and the ear of local leaders. Above all, they wanted the city to hire someone who could focus on downtown full time.

In fall of 2018, after elections ushered in a new mayor, Happy Mobelini, he and county Judge Executive Scott Alexander called up a bright young professional named Bailey Richards and asked her to apply. Bailey grew up in Cincinnati and moved to Hazard in 2011 for a job at the local newspaper after college.

[8:00]

RICHARDS: Neither of them knew me very well. I had moved here. I worked for the paper. I knew both of them through that, just from interviewing them for various things.

PIPA: Bailey worked with two different nonprofits after leaving the paper, and during that time she was just determined to become a homeowner.

RICHARDS: And then I got this idea in my head that I could buy a downtown building and turn it into my house, and I would live in this, like, kind of cool loft environment in this, like, rural downtown. And then I did it!

And it was the first building downtown that had been totally renovated and looked good. And so when all of that happened, Happy and Scott thought about doing this, and they were like, well, the only building that has been successfully converted and is now being used and was previously abandoned, it’s hers.

PIPA: On her second day at work, Bailey made her debut at a town meeting. Commissioners were voting to formally confirm her position and also to consider Sunday alcohol sales. After the meeting, she was packing up her things when a man approached her.

[9:03]

RICHARDS: And he was like, I don’t know why they hired you. Nothing’s gonna change, nothing’s gonna happen. They’re wasting their time and energy. And that was kind of the sentiment that I felt around the whole idea of this, that everybody had kind of just given up on downtown. That was just not the way that this was gonna work. This was not the future of it. So I felt a lot of pressure to prove that my job and my salary was worth doing and was worth something to accomplish.

So I decided, I was, like, I’m gonna take on as many little wins as I can really, really quickly so we at least have something to point to. Even if the big stuff doesn’t come for a while, what can I get done really, really quickly? So I would do things like, I would pull the weeds on Main Street myself. I would come out with, you know, a paintbrush and just paint over little things.

[music]

But, just like, those little things add up and people start noticing them over time.

PIPA: Bailey went on a fact-finding mission: Why do businesses choose to open in a rural town? Based on programs elsewhere, she helped create an incentive program to provide small grants for business owners—for things even as small as shelving or signage so would-be entrepreneurs could set up shop in Hazard. If a business owner needed to take a day off and couldn’t get a shift covered, it was often Bailey who spelled them behind the register.

In a nod to the kind of quirkiness that Kennedy Caudill talked about at top of the show, Bailey also started building and installing dozens of miniature ceramic doors on interesting or historic buildings in Hazard’s downtown. They were an Easter egg of sorts—and people would come downtown specifically to look for them.

[10:48]

RICHARDS: So, I wanted to get people to look at the assets again. And so when I did this huge project and nobody noticed it for a little while, I realized that I needed to shift people’s focus and give them a reason to have to look for the things that were good or were changing or were, you know, a positive whatever.

So I started this idea of tiny doors. And so I started building these little, tiny doors and putting them all over downtown. I let people find them on their own and a few people started posting about ‘em. And when that happened, it blew up. Then other people started making them, and I don’t know who all of those people are. But by the time the whole thing had kind of run its course, and it was a few years, there was probably 60 or 70 of them around.

And that was kind of something that I realized that, like, you can do these major huge projects, and that’s awesome and that’s great. But you gotta make people at least look at and appreciate the stuff that they already have in order to get them to accept and love what there is about their town.

PIPA: When Bailey started her work in the spring of 2019, she focused on a particular vacant building downtown: the old bus station which had closed seven years earlier. The Appalachian Arts Alliance had formed in Hazard to turn the space into a performing arts center. And with the support of a local bank, the Alliance developed a vision that earned them a half-million-dollar federal grant. Architects drew up plans, but when the Alliance put the work out for bid, proposals came in a million dollars over the grant amount. This cycle happened a few times before, eventually, they had to return the grant.

[12:28]

RICHARDS: And so it became this thing in the, like, nonprofit world that this was just a project that was never gonna happen. And so when I was hired, I was actually on the board of this organization and the mayor turned to me and was, like, if you’re on the board, if you can do nothing else in this job but get that stupid building open, I will consider this a success. And I was like, okay, great!

PIPA: Then one day, she was talking about these challenges with a couple of business owners from neighboring counties. One of them pointed out: you know, these improvements are really only suggestions.

RICHARDS: It hadn’t even dawned on me that you didn’t have to do all of this modernization, do all these things that the architects were telling us that you had to do, that you could keep, like, some of these things. And it was okay if it wasn’t perfect, and it was okay if it wasn’t perfectly energy efficient and up to the latest standards of this and that. And I was like, oh, so maybe we can start looking at these things as assets and we don’t have to look at them all as challenges.

So that was a big turning point. And, like, kind of accepting the building as it was, where it was, and the shape that it was, and just working within that really changed how we thought about that building.

[music]

And it took a project that was bidding out at over $1.2, $1.3 million and made it a $250,000 project that we were able to actually do.

PIPA: Not long afterwards, the Arts Alliance hired Tim Deaton as its executive director. Together, Bailey and Tim helped keep the project moving forward. The Art Station opened 15 months later in July 2020. These days, it’s where the kids from young families take Kindermusik classes together.

In the courtyard, a large metal sculpture in the shape of a tree stands as a community memorial to those who died during the COVID-19 pandemic and their loved ones—as well as the 2022 floods that hit Hazard and killed 40 people in Eastern Kentucky. Students used the new metalworking studio at Hazard High School to make leaves on what they call the Healing Tree.

It’s an example of how the town has leveraged the creativity of its youth, its strong civic spirit, and its artistic bent to create a community space that tells a story of loss, grief, but also resilience and hope, all at once.

At the opposite end of Main Street, there’s also now a gathering space where the historic Grant Hotel building used to be. It burned in 2015 and sat empty for years until its disposition was resolved through the courts, becoming too damaged by then to save even its façade. But tearing it down and turning into a welcoming gathering space adorned by a big, bright mural, has given Hazard creative, artistic gathering spaces at both ends of its downtown where the community gathers for music and events on a regular basis.

In addition to the civic spirit reflected in InVision and the capacity brought by a downtown coordinator, one of the other things that distinguishes Hazard is the Civic Fellows program. Since 2019, the youth participating in the program have designed signs for Hazard’s many unmarked cultural neighborhoods, explored the viability of a riverwalk in town, and developed a dog park from soup to nuts.

This summer’s Civic Fellows—Kennedy Caudill, plus Moriah Musick and Kailey Pennington—were not stuck behind a desk in city hall. They spent their time presenting ideas at public meetings, conducting research, visiting leaders in other Eastern Kentucky towns, and working on a joint downtown revitalization project. Moriah, who will start at George Washington University in the fall, speaks first.

[16:33]

MUSICK: So, over in Perry County we have the veterans, East Kentucky Veterans Center. There’s close to a hundred veterans that live there. So we’ve started to make banners for downtown to hang on the light posts that go throughout Main Street with the names, faces, ranks, and branches of Perry County veterans. And then we are also taking their oral histories and making a database, and a website hopefully will be up and running to tell their stories.

PIPA: Outside of the fellowship, these students are involved in their community. This past school year, Kailey presented her work on a separate project focused on kids with special needs. City officials regularly attend these events, and the local Chamber of Commerce director Betsy Clemons urged her to apply for the Civic Fellows program.

[17:21]

PENNINGTON: So I’m very passionate in special needs. And we have a program at Hazard High School called CARAT-TOP. And we basically focus on betterment of lives of special needs individuals. And at our end of year presentation that specific year we had made toys, like, adapted toys for kids with special needs.

PIPA: When Kailey starts her junior year this fall, she’ll be busy at work on another project, specifically for this underserved community: an inclusive sensory park—play spaces for people with sensory-processing issues.

PENNINGTON: Happy approved our sensory park last … in the spring, and I get to help design it. The goal is to focus it to be for as many special needs individuals as possible. So yes, it’s gonna be autism geared, but also for cerebral palsy, and Down syndrome and other disabilities too.

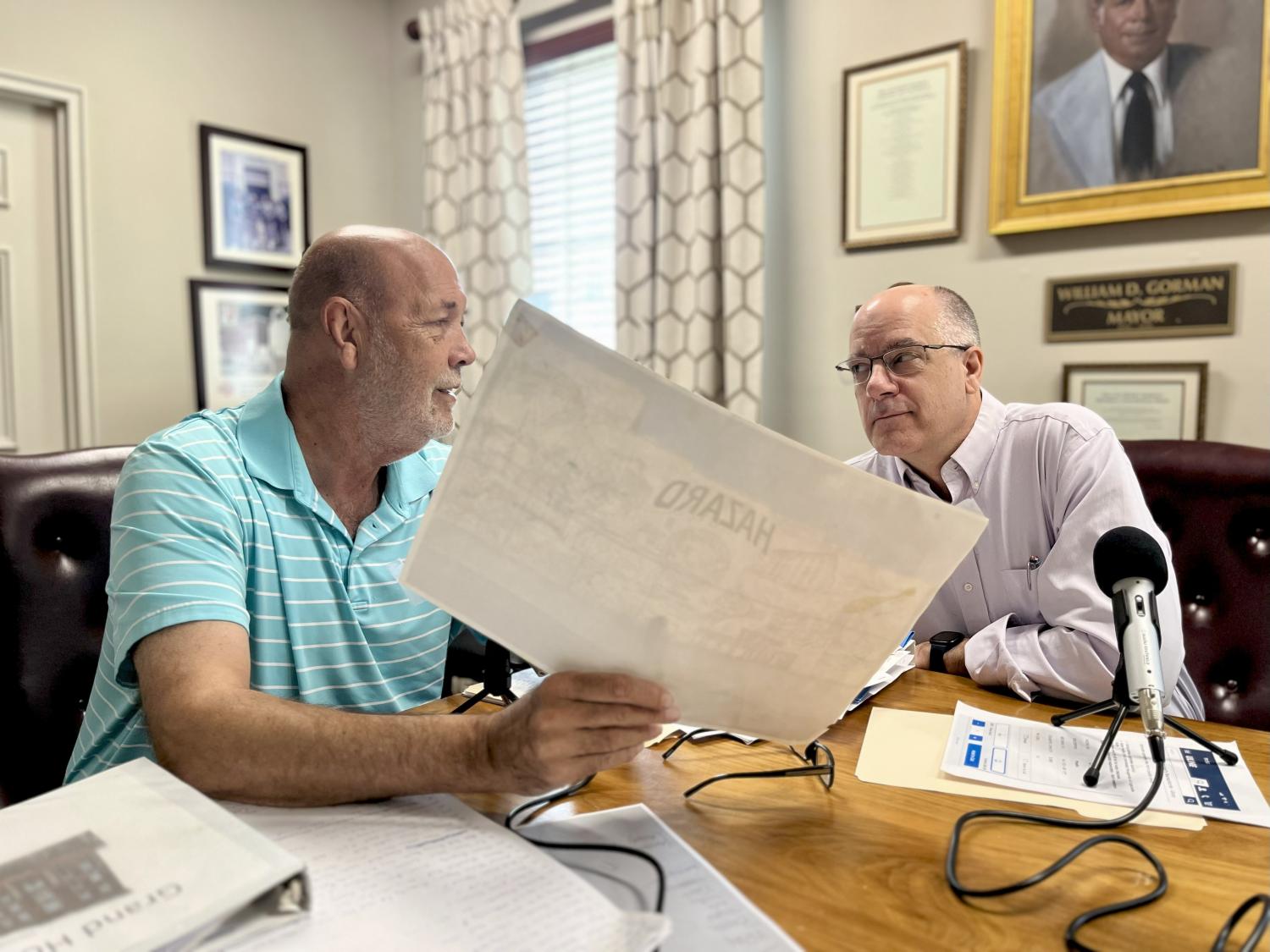

PIPA: “Happy” is the nickname for Donald Mobelini, the mayor of Hazard and the retired principal of Hazard High School.

[18:23]

MOBELINI: At one time we were the Queen City of the Mountains. We really were the hub for all of Eastern Kentucky. And that’s when the coal business was booming and all that type of stuff. But then, you know, obviously we lost our coal industry. And, and just at the last Census, all counties around us in Eastern Kentucky lost people. They’d moved away because of migration for jobs and things. We didn’t. We don’t have any more coal companies; we have maybe one or two that’s working as opposed to 30 that we used to have. But we actually gained people moving back here. We’ve been really conscientious of trying to recreate ourselves.

How many small towns of 5,000 have 20 high school or college kids doing an internship program in your city and learning how the government works? And here’s the other thing, these kids got a seat at the table. If they come up with a good idea, we’ll do it. If they come up with a bad one, we’ll laugh and say no.

[music]

To me, I think that we’re very progressive in that sense.

PIPA: So as I mentioned before, the Civic Fellows Program is the brainchild of Luke Glaser, who’s not only on the town council, but is the assistant principal at Hazard High School, where he’s also an AP calculus teacher, the assistant soccer coach, and was a semifinalist for the 2024 Kentucky Teacher of the Year award. But Luke’s not a native; he grew up in Louisville, Kentucky’s largest city.

[19:59]

GLASER: So when I was in high school, what I knew, I knew two things about Eastern Kentucky, right? Somewhere past the Gorge, everything became black and white ‘cause all the pictures from Eastern Kentucky were of sad people and they were in black and white. And that’s where you went on alternative spring break trips because they couldn’t build schools or houses themselves. And those are horrible two things to think, but I didn’t know any better. Right? That’s just what I was receiving up in Louisville.

So in college I had the opportunity to go down to Whitesburg. And I was part of a a fellowship at the University of Kentucky, and two board members invited us down for the weekend. And I found all those presuppositions upended, right? There were brilliant people here who could be doing anything, but they were working and living in Eastern Kentucky because they loved it here and because they were passionate about it. And that really stuck with me, and I wanted to explore that a little bit more.

PIPA: Luke’s original plan included law school but he found his calling when he signed up for the Teach for America program in 2013 and landed in Hazard.

GLASER: When I first joined Teach for America, they were like, be careful. They’re wary of outsiders, they’re suspicious of outsiders. And I never found that. I thought people were just fascinated with the fact that you had chosen to be here of all places, and they were super welcoming about that, and they were very accommodating, and very curious about your story.

I joke that I’m 14 years into my two-year commitment. I just fell in love with the place. I fell in love with the people. They’re the kindest, most generous people that I have ever met, and I am privileged that they let someone like me be a part of this revitalization and this renaissance that we are now under undertaking.

PIPA: Luke’s a big Hazard booster in his personal life, too. While we were walking around downtown together, he revealed that it had been the setting for a very special occasion.

[21:37]

GLASER: My wife and I, when we got married, we had our reception on Main Street. We blocked it off in front of the courthouse ‘cause I wanted all of my relatives and and friends to see all of this work that we had done down here and built together. And I think the downtown businesses did, like, double their normal business for the weekend?

RICHARDS: Oh, yeah. I actually did a little bit of a, like, economic impact study, just like a very, like, cheeky under the table quick one —

PIPA: — of Luke’s of Luke’s wedding?

RICHARDS: — of Luke’s wedding. And it was, depending upon what it was, doubles what some of our, like, large festivals were. Because his family came in and they knew how much he loved and cared about this place and decided that they were gonna support all of the local things that he loved.

GLASER: And, and the welcome bags were all, like, discounts to the stores. So we kind of pushed it a little bit.

RICHARDS: Yeah. But it was awesome.

GLASER: It was a really, really beautiful evening.

RICHARDS: Yeah.

PIPA: All right!

RICHARDS: Great, we’ll go this way.

PIPA: All right.

[22:33]

GLASER: There’s not a lot of messaging for young people in small towns that say, you can live a good and happy, fulfilled life here in the community that you grew up in. And in fact, we need you here. This town … like it’s math, if more people are leaving than coming in or coming back, the community will eventually die. It may not happen tomorrow, it may not happen 10 years from now, but it will eventually happen.]

PIPA: During my visit, I joined Luke and the three Civic Fellows for lunch at a restaurant in Downtown Hazard. It felt a bit like a book club—and that’s because a shared reading experience is one of three goals of the fellowship program. In this case, they were all reading Hollowing Out the Middle, a classic analysis published in 2010 about the exodus of bright young adults from rural areas that, for better or worse, helped popularize the term “rural brain drain.”

[23:32]

GLASER: So the author described the decision to leave or stay as a reflection of resources and the messages they received from their social networks. What messages do you guys receive about leaving here or staying here, or somewhere in between?

PENNINGTON: I would honestly say it’s really mixed. Like, I have people like Betsy that I think are gonna lock me in a basement if I don’t come back.

GLASER: Right.

PENNINGTON: And then I have people in schools and teachers that are, like, there’s better for you out there. So, I mean, It think it’s a little bit of both.

GLASER: You don’t have to name teachers, it’s okay. But like when they say there’s better for you out there, what do they mean by that?

PENNINGTON: There’s more opportunities, there’s more jobs, there’s higher educational opportunities than what you can achieve here.

CAUDILL: When you’re an employee of the City of Hazard, you feel like it’s kind of like an obligation to stay, if that makes sense.

GLASER: Yeah, yeah.

CAUDILL: Like I’ve put a lot into Hazard, if that makes sense.

GLASER: It does.

CAUDILL: It feels like I owe a debt to the people here for what I’ve done, like, what the opportunities I’ve been given here, I feel like I owe the debt to those people. If that makes sense.

GLASER: Is it, is it like a guilt thing? Like, I want to move away, but I’m not going to ‘cause I owe these people so much. Would you describe it as, like, a guilt thing?

CAUDILL: To the extent maybe? I I love it here.

GLASER: Okay.

CAUDILL: And I don’t see myself being away from here for, like, an extended period of time.

GLASER: Yeah.

CAUDILL: But, like, I do like to explore my options, but I do feel like sometimes it holds me back being, like, I owe this community a lot. Because I do, ‘cause I’ve been given so many opportunities that, like, I can’t pass up on the people that go gave those opportunities.

GLASER: Sure. Okay, so

PIPA: Luke, can I ask a question?

GLASER: Yeah, please.

PIPA: So on the messaging, what are your friends what, what, what do you hear from your friends about pit in or about going or, or staying?

[25:21]

MUSICK: My friends were actually kind of upset with me that I was upset over UK not working out. ‘Cause where I, my dad works at UPike, I would be ___ on full tuition. They were like, why don’t you just go to U? Like, you’re complaining and you’re wasting this free tuition opportunity at UPike just to get a political science degree. And I was, like, you’re missing the point.

GLASER: What is the point?

MUSICK: I think I told you this in my interview, but I’m not sure if I can if I said exactly this, but I wanna work in a bigger city to help the smaller cities, not live in a smaller city.

GLASER: Sure sure. It’s it’s interesting you say that, Moriah, ‘cause there, you know, one of the goals of this fellowship is to get kids thinking about what would it look like if I moved back? That doesn’t mean it’s a failure if kids don’t move back. Right? It’s just like, you know, the idea is to get you looking at how to run things and how to be in charge and how to make your own decisions. And, you know, there are, there are students who aren’t here anymore that are still doing good work. And and and Hazard will benefit that from that indirect, indirectly.

What about your all’s peers?

[26:22]

CAUDILL: So, for me, the end of my senior year, I was stuck between staying here and going to Eastern. Like, there’s this phase where, like —

GLASER: — HCTC you mean?

CAUDILL: Yeah.

GLASER: Okay.

CAUDILL: Where —

GLASER: — Hazard Community Technical College —

CAUDILL: — where I wanted to do physical therapy, right? And I, they have a PTA program. And I was stuck between doing that or going to Eastern. So, you know, as most of … I asked all my friends and I think every single one of ‘em but one said, you need to go to Eastern. Because the expectation is you don’t wanna get stuck here.

GLASER: Right.

PIPA: So do you think they’d see you as a failure if you stayed here?

CAUDILL: I, to be honest I feel like they would, yeah. I feel a lot of people would be like, he couldn’t leave Hazard, he was stuck in …

PENNINGTON: I feel like I’m one of the few and far between teenagers that are gonna say I love this place, and I don’t want to leave.

GLASER: I got into an argument once with a woman, we were in a group together and I brain drain is like my passion, like it’s like what I talk about —

PENNINGTON: — really?

GLASER: And she was, like, there’s not a brain drain issue here. And I was like, what? And she was, like, studies show that most people live within two miles of their parents. And I was like —

PENNINGTON: — yes, exactly.

GLASER: Well, I I had to think about it, and I had to, like, go back and and, like, look at some data. And, A, she’s wrong statistically, like there is a brain drain issue here.

But, like, my point to her was, like, if I’m standing on stage at your graduation and I’m looking at the valedictorian, the chances of that valedictorian staying here are much much lower than, like, other people in the class. Right? It’s it’s it’s it’s kind of harsh to say, but —

PIPA: — even the honor students.

GLASER: Right right. And and and, you know, from a from a city leader perspective, if we’re looking at who has the not not the only chance, but the best chance of, like, being a game changer here, it’s probably those kids.

Now the beautiful thing about entrepreneurship is it can come from anywhere. But, and we’re gonna talk in this book about how schools maybe need to change a little bit to cultivate that, but that was my point, is that it’s not just how many are leaving, but who is leaving.

PIPA: I visited Hazard on July 4th for the annual Independence Day celebration and fish fry.

[28:36]

MOBELINI: And we got stuff all day long. After this we’ve got those lawnmower races, and we’ve got the bicycle parade. We got everything like that. So stay around. And then tonight, we have two concerts down here, Midlife Crisis and the children’s concert before that. But before we start the food, I’d like to ask Bam, who’s head of our public works maintenance department, he’s going to lead us in prayer.

SPEAKER: Heavenly Father. Thank you for another beautiful day you have blessed us with and a little time just to gather together here, Father and just have fellowship one from the other Father. Our Father we do want to thank you …

PIPA: Hundreds of people lined up in the summer heat for the catfish being fried by the volunteers from the fire department. The Civic Fellows—Kailey, Kennedy, and Moriah—were there, of course, helping portion out servings.

SPEAKER: [… prayer continues]. Amen.

CROWD: Amen.

MOBELINI: And if you see the guy up here in the red shirt, if you’ll make a line behind him, we’ll get you served as fast as possible.

PIPA: We took a break from the heat to talk more about the Civic Fellows’ summer projects and their impressions of Hazard.

[29:49]

CAUDILL: Hazard is a very diverse place. On the surface, it may not seem that like it, ‘cause you go to Eastern Kentucky, it’s be like just a bunch of straight white males. But, we have a very, especially for Eastern Kentucky, we have a very diverse population. And there’s a stigma around Eastern Kentucky and the South in general is, like, we don’t accept those people. It don’t matter who you are in Hazard, we’re gonna take you in with open arms.

PENNINGTON: I mean, at the end of the day, we are a predominantly conservative community, but everyone is welcome. There’s always gonna be people anywhere you go that’s gonna be judgmental and rude and that kind of stuff.

MUSICK: I’ve not been in Hazard very long, but I am more involved in my community back in home in Pikeville. And we do have one of the only Pride events that goes on in Eastern Kentucky. And there definitely has been pushback. My dad’s very involved with helping it get run. But I think no matter what, they will keep going. And Hazard is very similar. And they just won’t take no for an answer. And it’s beautiful.

PIPA: Since Bailey Richards started in her role in 2019, she says 75 new businesses have opened in downtown Hazard alone. Not all of those have survived—it’s been an especially difficult few years for small business owners, between the COVID pandemic and damage from flooding. She estimates a fifth of those new downtown businesses are owned or run by people in substance use disorder recovery.

One of those businesses is the Read Spotted Newt, a beloved local bookstore. Owner Mandi Fugate Sheffel specializes in Appalachian literature and nonfiction. She herself has a forthcoming memoir — a first-hand account of her own addiction and recovery.

In 2019, Mandi had just finished a master’s degree in environmental health and safety and while looking for a job in her field in Eastern Kentucky, starting thinking about what it would be like to open a bookstore.

[31:50]

SHEFFEL: Growing up in Eastern Kentucky as a reader, a lifelong reader, our closest bookstore is two hours away in Lexington. And that had been the case my whole life into my adult life. There’s never been an independent bookstore here. And, and I thought about all the other people that I knew who were readers. We would make a couple of trips to Lexington a year, and that was always a part of the trip. And I also thought about all the people, especially kids, who didn’t have the benefit of traveling to Lexington, because a lot of people from this region just don’t travel outside of the region. They don’t have the means to travel outside of the region.

[music]

So I just offhandedly was having lunch one day with my mom and I was, like, you know, I’d really like to open a bookstore. I think every small town needs a bookstore, because when I travel, that’s what I look for is the cool independent bookstore in whatever town I’m traveling to. And she was like, yeah, that would be super cool, I think that would work. She may have been the only one that said they thought it would work.

And so we actually, like, that day she was, like, let’s call Bailey and see what kind of space that she thinks may be for rent.

PIPA: She opened inside a tiny space—just 250-square-feet—in January of 2020.

SHEFFEL: And so what would that mean for people here to have a bookstore locally and close to home? And access to writers and authors, because we have such a rich literary tradition in Eastern Kentucky and Kentucky in general. And to bring those writers into the community and be able to engage with them one-on-one in a bookstore that the community could call its own? So all of this was also in the back of my mind.

I’m like, I’m gonna offer books that people can’t get. You can go to Walmart and get the latest Stephen King or Nora Roberts or John Grisham, but you can’t go to Walmart and get Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, who is the first published novelist out of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. You’re not gonna find that at Walmart, but you can find it at Read Spotted Newt.

And so these are the voices of Appalachia that weren’t getting heard, and that also was in the back of my mind. It was about narrative change for me. I was so tired of being from here and people thinking that we were all backward and conservative and religious and illiterate. Like, I was tired. I was tired of it, you know. After 43 years of growing up here and constantly having to fight, you get tired.

[lawnmower sounds]

PIPA: The defending champion of the of the push mower race is Steven Prosser, who we interviewed, owner of Hazard Coffee Company. Steven, what’s the prize?

S. PROSSER: Last year it was a, like, a golden lawnmower blade. I would assume it’s similar this year, but I’m not sure.

PIPA: The golden lawnmower blade now on your mower?

S. PROSSER: No, it’s hanging out it’s hanging up in the coffee shop, actually. I think we get like, a a Duke or a Duchess of Hazard thing, you know? They usually like to do that for fun events, if you win something, they’ll do give you a Duke of Hazard certificate.

PRODUCER: Love that.

ANNOUNCER: On your mark, get set, go!

PIPA: And I think Steven Prosser is going to easily defend his title today.

PRODUCER: He looks like he might be a runner, Tony!

PIPA: Stephen Prosser won the push lawnmower race. He and his wife Maggie own the local coffee shop. Covid brought them back to Hazard, Maggie’s hometown. In March 2020, Maggie’s mother was visiting the couple in Dallas and as the COVID lockdowns began decided to extend her trip. In July, the three of them drove 15 hours back to Hazard together. Stephen had grown up in Georgia, and he and Maggie had met in Lexington years earlier but hadn’t planned to return to Kentucky right away—and Hazard wasn’t on their radar at all.

[36:18]

M. PROSSER: Our son was about 18 months old. And we did a lot of just hiking and we went to the farmer’s market all the time —

S. PROSSER: — yeah, that was great —

M. PROSSER: — and really started to see and hear about some of the changes that were going on in the town. And we were, like, I think we could live here. And we, which was not something that I had considered when I was growing up here. You know, you grow up in a place and you think, I’m gonna go somewhere so different and I don’t want to be in the, you know, same place where I started.

And we were, like, Hazard doesn’t have a coffee shop. So we weren’t necessarily, we didn’t start off, like, we love coffee so much, let’s open a coffee shop. It was, what does Hazard need? And we thought, you know, every downtown needs a coffee shop, a place for people to get together. And so that’s sort of where we started. We had some good local beans, and locally roasted beans, and Hazard needed a coffee shop.

PIPA: Hazard Coffee Company opened in May 2021. The rent was affordable — just $350 a month — and they got $5,000 from Hazard’s Downtown Incentive Program. They also participated in Invest 606, a business accelerator and pitch contest.

[37:23]

S. PROSSER: So our year, we tied with the bookstore, actually with Read Spotted Newt, and split the third place prize. But that really wasn’t the big deal. The big deal was we had then had access to financing, low interest financing.

It was the right time, and we were able to move here, and we had to, you know, get more machines, fund more staff, and and thinking about the amount of staff that we employ now is crazy for me.

It’s a function of the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky, which which also is a huge supporter. They do so much in town. Having a non-profit that champions so much of Eastern Kentucky in your downtown is —

M. PROSSER: — is great.

S. PROSSER: Oh, it’s fantastic.

PIPA: Maggie and Stephen roast their own beans now. A little over a year later they opened a second location in another small town close by. Like the original location in downtown Hazard, it started off pretty slow — in both places, they had to build a name, become part of people’s routines.

So has it all been worth it?

[38:22]

M. PROSSER: Just seeing our son in the community has been, I think that makes everything worth it because it’s just such a magical childhood, honestly.

S. PROSSER: The city’s had its own fair share of struggles, but I think what’s really cool about Hazard in general is the growth that it’s experiencing. But everybody wants Hazard to be successful in a positive way that is successful for the community, not for themselves. That’s what it feels like from the outside looking in. Right? That it’s not that somebody’s trying to come in and, like, take over everything or something and run the town into the ground just for power or something, you know? Because sometimes you hear about that in small town politics that that people kind of run stuff. It doesn’t feel that way here.

[music]

It just feels like people are making Hazard a wonderful place to live because it should be. And everybody should experience that.

PIPA: A strong civic spirit. Real engagement and belief in their youth. Stalwart partners such as the Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky and Mountain Association, which have been investors in some of the projects you’ve heard about today. And a keen sense of their history and identity, which is quirky, creative, and is welcoming in its own special way.

Perhaps those elements do make them the odd cats of Appalachia, as Kennedy Caudill says. Heck, the town is home to the Mother Goose House, an 85-year-old roadside attraction that is one of the most photographed locations in Eastern Kentucky.

But it’s quite clear that Stephen Prosser’s words also ring true: It just feels like people are making Hazard a wonderful place to live because it should be. For me, that made it a perfect place to spend some of the Fourth of July, the holiday during which, as a country, we all renew our civic vows — because Hazard’s resilience and buoyancy amply show what can happen when, together, a community takes those civic vows seriously.

Thanks for listening.

[clip of radio program]

My sincere thanks to all the people who shared their time with me for this episode.

[music]

To provide further policy insights based on this episode, we also publish a Q&A with an outside expert on the Brookings website. You can find the link in the show notes.

Many thanks to the team who makes this podcast possible, including Fred Dews, supervising producer; Molly Born, producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video manager; Zoe Swarzenski, senior project manager at the Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings; Adam Aley, Kevin Martinez, and Elyse Painter, also in the Center for Sustainable Development, who provide research support and fact checking; and Junjie Ren, senior communications manager in the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings.

Also, my sincere thanks to our great promotions team in the Brookings Office of Communications and Global Economy and Development. Katie Merris designed the beautiful logo.

Finally, support for this podcast is provided by Ascendium Education Group. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication or podcast are solely those of its authors and speakers, and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or its funders. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

You can find episodes of Reimagine Rural wherever you like to get podcasts and learn more about the show on our website at Brookings dot edu slash Reimagine Rural. You’ll also find my work on rural policy on the Brookings website.

If you liked the show, please consider giving it a five-star rating on the platform where you listen.

I’m Tony Pipa, and this is Reimagine Rural.

More information:

- Listen to Reimagine Rural on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

- Find out more about the Brookings-AEI Commission on U.S. Rural Prosperity.

- Discover more research on Reimagining Rural Policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastHazard, Kentucky’s civic renaissance is changing the narrative about Appalachia

Listen on

Reimagine Rural

August 19, 2025