There are many factors at work in determining educational outcomes; some of these are more easily addressed by policy reforms than others, and not all can be addressed directly within the K–12 education system. To illustrate the payoffs from increasing educational attainment, the challenges faced by our nation’s K–12 schools, and the promise of targeted childhood interventions, The Hamilton Project offers the following fourteen facts on education and economic opportunity.

Introduction

Education is a powerful force for advancing opportunity, prosperity and growth. Educational attainment is a significant determinant of a range of measures of well-being, including an individual’s likelihood of marrying, owning a home, or living a long life, as well as her likelihood of being arrested. Educational attainment is also a key determinant of economic success. A strong education system is fundamental to ensuring that all Americans have the opportunity to acquire the skills they need to thrive.

Read the full introduction »

The Hamilton Project supports policies that foster economic growth and broad-based participation in that growth. For the past decade we have emphasized that evidence-based improvements to public education are essential to the success of our economy and society. As the following fourteen facts demonstrate, the evidence makes an overwhelming case for policy changes in education.

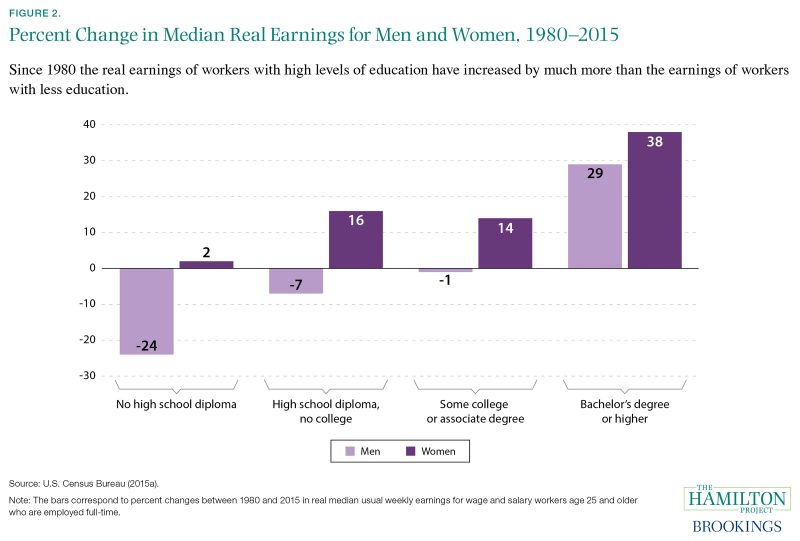

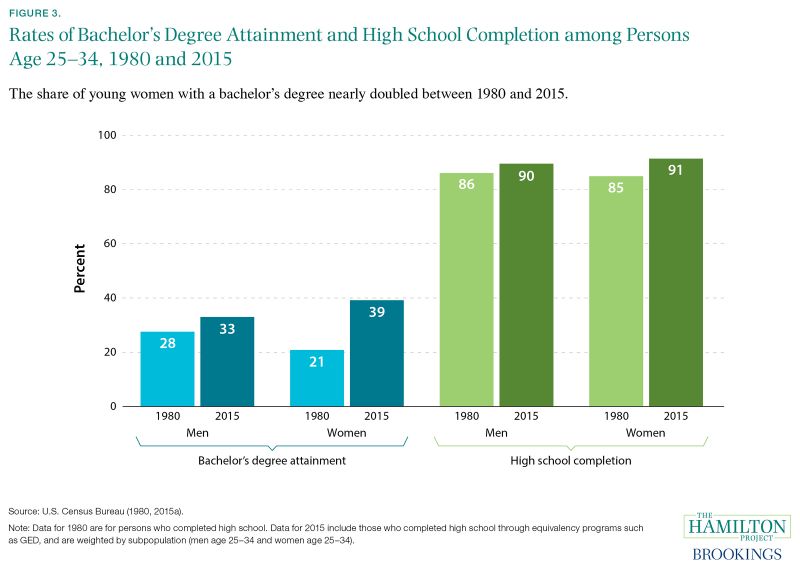

Over the past three decades the gap in earnings between workers with high levels of education and those with less education has grown substantially (see Fact 2). For men, median real earnings increased only among those with college or advanced degrees: their earnings are 29 percent higher than they were in 1980. Men with less than a bachelor’s degree have seen their real earnings stagnate or decline, with an especially large drop among workers with the lowest levels of education. In contrast, women have seen their real median earnings increase across all education levels, with a nearly 40 percent increase among college-educated women. The share of young women with a bachelor’s degree has also increased over the past three decades, almost doubling for women age 25–34 from just 21 percent in 1980 to 39 percent in 2015. The rate of high school completion (including GED attainment) among young women also increased, rising 6 percentage points over this period to 91 percent. The share of young men who completed high school also rose, but by less than the gains among women (see Fact 3).

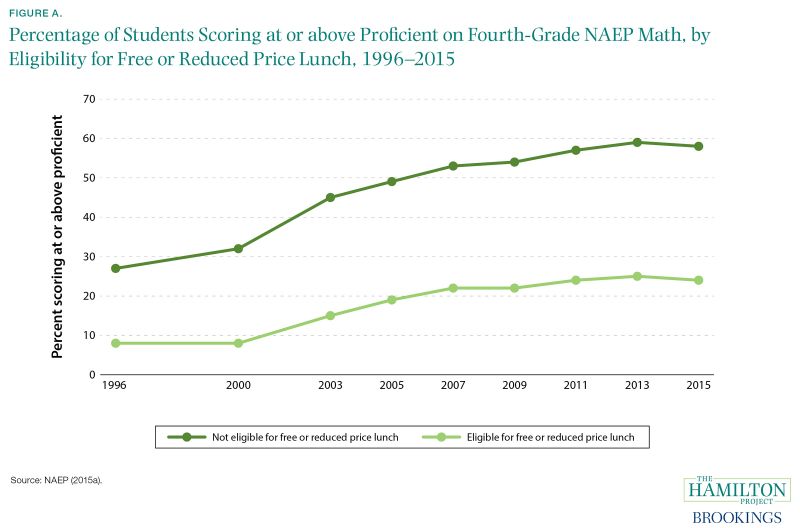

Over the past 20 years both high- and low-income students have made strong gains in math achievement, with the share of fourth-grade students scoring at or above proficiency in math in 2014 substantially higher than in 1996. In fact, low-income students’ proficiency rates tripled over this period. However, there remain large and persistent gaps in skills between high- and low-income students, as illustrated in figure A. Math proficiency rates among low-income students were still lower in 2015 than high-income students’ rates in 1996. Identifying ways to close these achievement gaps is perhaps the largest challenge facing K–12 education today.

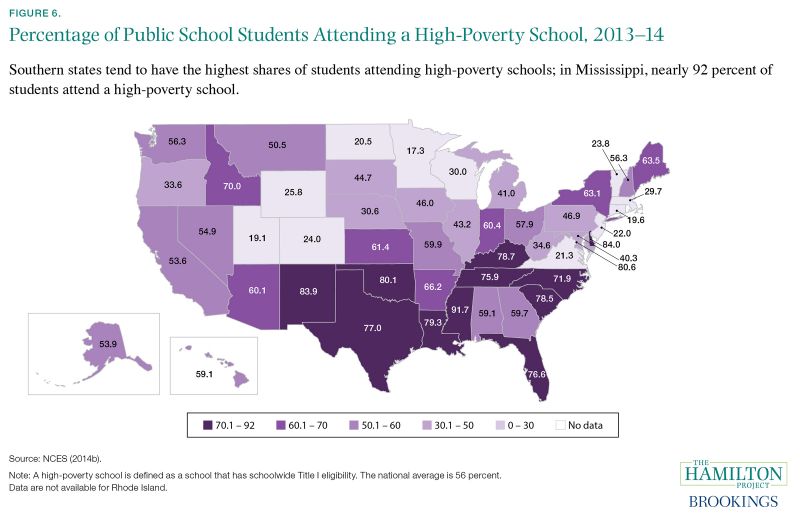

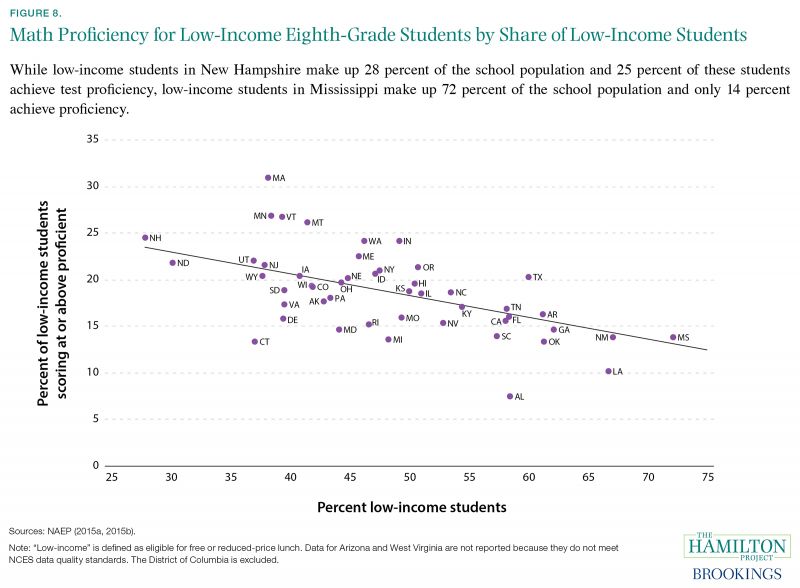

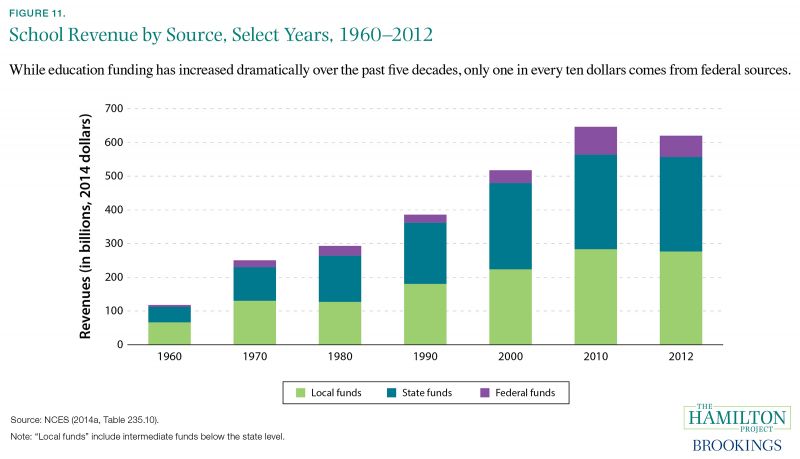

Large differences in skills between high- and low-income students make it especially daunting to address disparities in student achievement, in part because these disparities reflect broader economic challenges such as the large share of children living in poverty and, in particular, the high concentration of poverty at the school level. In 2014 a majority of public school students nationwide attended high-poverty schools—defined as schools in which more than 40 percent of students are low-income (see Fact 6). At the state level, performance among low-income students declines as the share of low-income students in the state increases (see Fact 8). This may partly reflect differences in access to resources: while education spending overall has steadily increased each decade over the past 50 years (see Fact 11), spending is highly uneven across states because most local education budgets are funded by state and local revenues (see Fact 10). In fact, some northeastern states spend about twice as much per student as states in the South and West, even after adjusting for variation in cost of living.

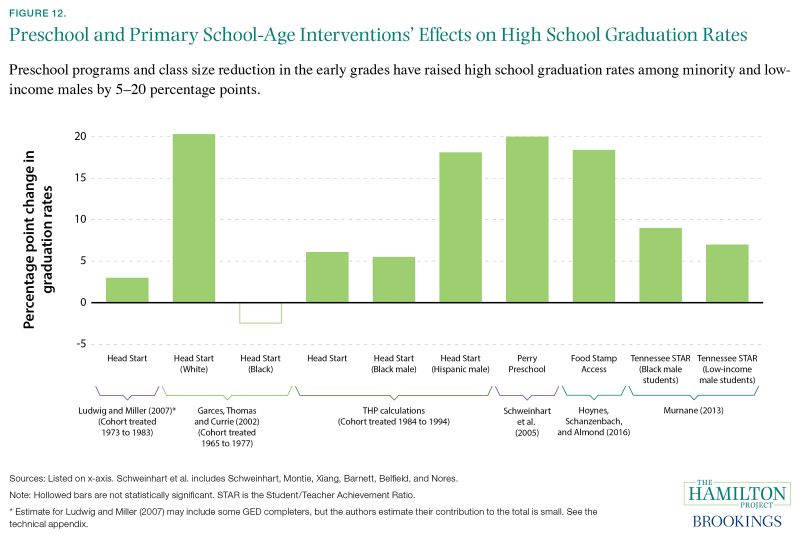

There are several promising interventions that have been shown to improve test scores and high school graduation rates, especially among low-income students living in areas with high concentrations of poverty. The charter school sector serves a small but increasing share of students, and achievement gains among students attending these schools can be quite strong in some cases (see Fact 14). An emerging stream of evidence also shows that interventions aimed at younger children—such as preschool programs and class-size reduction in the early grades—can improve high school graduation rates (see Fact 12) and students’ later economic outcomes.

There are many factors at work in determining educational outcomes; some of these are more easily addressed by policy reforms than others, and not all can be addressed directly within the K–12 education system. To illustrate the payoffs from increasing educational attainment, the challenges faced by our nation’s K–12 schools, and the promise of targeted childhood interventions, The Hamilton Project offers the following fourteen facts on education and economic opportunity.

Chapter 1: The Payoff to Skills is High

Fact 1: Both cognitive and soft skills—such as perseverance, tenacity, and social skills—play an important role in shaping economic outcomes.

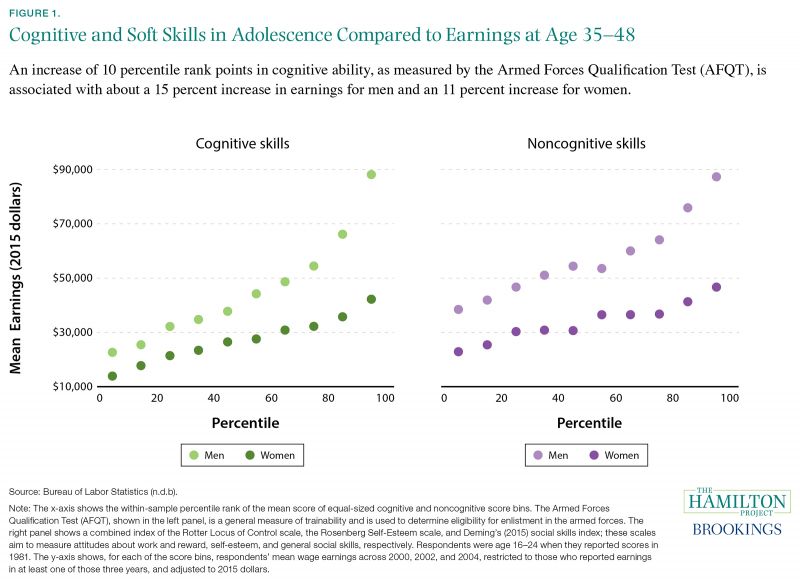

Skills are an important determinant of workers’ earnings and employment opportunities. No test perfectly measures the skills relevant to economic success, but tests that aim to measure analytical ability often do correlate with outcomes in the labor market. For example, the left panel of figure 1 shows a correlation between scores on the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) and earnings in middle age. Stronger analytical skills as measured by the AFQT correspond to higher wages, resulting in the upward sloping pattern shown in the figure. A similar relationship holds for measures of a range of analytical skills, such as verbal reasoning and problem solving. As seen in the figure, the relationship between AFQT scores and earnings is different for men and women: a 10-point increase in AFQT is associated with about a 15 percent increase in earnings for men but an 11 percent increase for women. Skills measured as early as kindergarten have a positive impact on adult earnings (Chetty et al. 2011).

Employment outcomes also depend on soft skills—a bundle of character attributes (sometimes referred to as noncognitive skills) that includes motivation, perseverance, tenacity, creativity, self-control, and the ability to work productively in groups (Deming 2015; Heckman, Stixrud, and Urzua 2006). The right panel of figure 1 shows on the horizontal axis a combined index of three scales that measure social skills, self-esteem, and the extent to which a person believes that her own actions, as opposed to forces outside of her control, determine rewards and success in life. The upward sloping pattern indicates that, by this measure, those with higher noncognitive skills also earn more, on average. The relationship between this noncognitive index and earnings is similar for men and women: a 10-point increase in the noncognitive index is associated with about a 7 percent increase in earnings for both men and women. Emerging research has found that both cognitive and soft skills can be taught, but that the teachers who are effective at raising cognitive skills are not necessarily the same teachers who are effective at imparting soft skills (Jackson 2012; Kraft and Grace 2016).

It is important to note, however, that tests of both cognitive and soft skills are correlated with other factors that influence employment outcomes, such as educational attainment, parents’ income, and the neighborhood environment. This makes it difficult to measure precisely the relative importance of these other factors compared to skills in determining a young person’s later economic success. Compounding this difficulty is the fact that skill formation is a cumulative process in which experiences in early childhood and adolescence lay the foundations for future learning. This cumulative feature is partly attributable to perceptions of elf-efficacy: early success at learning not only makes later skill-building easier, but also shows that effort has rewards, which can create a self-reinforcing motivation to continue learning (Heckman 2006). The flip side is that impediments to early learning can have cumulative negative effects on later skill formation. Such obstacles are particularly troubling given that the effects of skills on economic outcomes reach far beyond earnings; early childhood test scores are correlated with high school graduation rates (see Fact 12), college attendance, marriage, home ownership, and retirement savings (Chetty et al. 2011).

Fact 2: The skills premium has increased dramatically.

The gap in earnings between high-school-educated and college-educated workers has more than doubled in the United States over the past three decades (Autor 2014). Although a large number of developed countries show a similar trend, the United States appears to have the largest skills premium—that is, the gap between the wages of low- and high-skilled workers. In part, the magnitude of this gap reflects the fact that the inflation-adjusted earnings of workers with high levels of education have risen much more over the past 35 years than have the earnings of less-educated workers, as shown in figure 2. In fact, real earnings for men without a bachelor’s degree have actually fallen since 1980—and fallen dramatically for men with no high school diploma, whose earnings are down by more than 20 percent. Gains in earnings for women with a bachelor’s degree or an advanced degree were more than twice as large as those for women with a high school diploma, some college, or an associate degree. However, earnings for women at all education levels tended to increase at a higher rate than they did for similarly educated men. The differences may be partially explained by a lower initial level of earnings for women relative to men.

In recent decades the growing earnings premium for education has contributed substantially to the net growth of earnings inequality. Roughly two-thirds of the overall increase in earnings dispersion between 1980 and 2005 is accounted for by the rising returns to schooling—primarily the growing premium to postsecondary education (Goldin and Katz 2007). To exclude the effect of the very top and bottom of the earnings distribution on growing inequality, one can compare earnings at the 90th percentile of the wage distribution to earnings at the 10th percentile. This 90/10 ratio has also grown substantially in recent decades. Fully 95 percent of its growth between 1984 and 2004 was attributable to rising returns to education (Fortin, Lemieux, and Firpo 2011). In other words, if the education premium had remained constant, there would have been essentially no increase in wage inequality between 90th- and 10th-percentile workers.

Why has the education premium risen in recent decades? Economists continue to study this question, but a number of studies point to the interplay of supply and demand for skills. In The Race between Education and Technology, Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz (2008) make the case that the U.S. economy prospered during the twentieth century in large part because educational attainment kept up with the rising demand for skills, which was catalyzed by significant technological change. The labor market’s demand for analytical skills, written communications, and specific technical knowledge increased dramatically. Between 1900 and 1980 Americans kept pace by steadily increasing their level of education, reflecting in large part the country’s commitment to a secondary school system essentially free and open to all (Goldin and Katz 2008). Yet over the past three decades the rise in educational attainment has slowed, even as technological progress—and the corresponding demand for skills—has accelerated. Goldin and Katz (2008) succinctly capture the essence of the story: “In the first half of the century, education raced ahead of technology, but later in the century, technology raced ahead of educational gains” (p. 8).

Fact 3: Educational attainment has increased in the United States, especially among women.

Despite a slowing pace, educational attainment in the United States has gradually risen over the past 35 years, as shown in figure 3. The share of young women with college degrees almost doubled, from 21 to 39 percent, and young women are now more likely than young men to have a college degree. As shown in Fact 2, this has coincided with large increases in the wage premium for women with college degrees. High school completion rates have also increased over this period. From 1980 to 2015 the share of American men age 25–34 that completed high school inched up from 86 to 90 percent, and rose from 85 to 91 percent among women.

Nonetheless, many researchers worry that skill levels among young people in the United States are far too low. Historically, successive generations have attained more education at a rate of approximately one additional year of schooling every decade; for example, individuals born in 1930 averaged about 11 years of schooling by the time they reached age 30, compared with 13 years for people born in 1950 (Goldin and Katz 2008). But for individuals born around 1950 and later, this pace was roughly cut in half, even though the economic returns to education have increased (see Fact 2). Individuals born around 1985, who were 30 years old in 2015, averaged 14 years of schooling.

There is concern among some researchers that public policies aimed at improving skills and educational attainment are too often evaluated on narrowly defined criteria such as conventional cognitive test scores. For example, in the 1960s the Head Start program was thought to have fallen short of its goals because it did not permanently raise the IQs of its participants. This kind of write-off may be premature in light of evidence from early childhood interventions such as the Perry Preschool Project, which had lasting benefits that were not picked up by conventional measures of cognitive ability (Schweinhart et al. 2005). In particular, by age 10 the IQ scores of the participants were no higher than those of the control group, but the participants did show more motivation to learn, and by age 40 they were more likely to have graduated high school, to be earning higher salaries, to own a home, to be less dependent on welfare, to have had fewer out-of-wedlock births, and to have not been arrested.

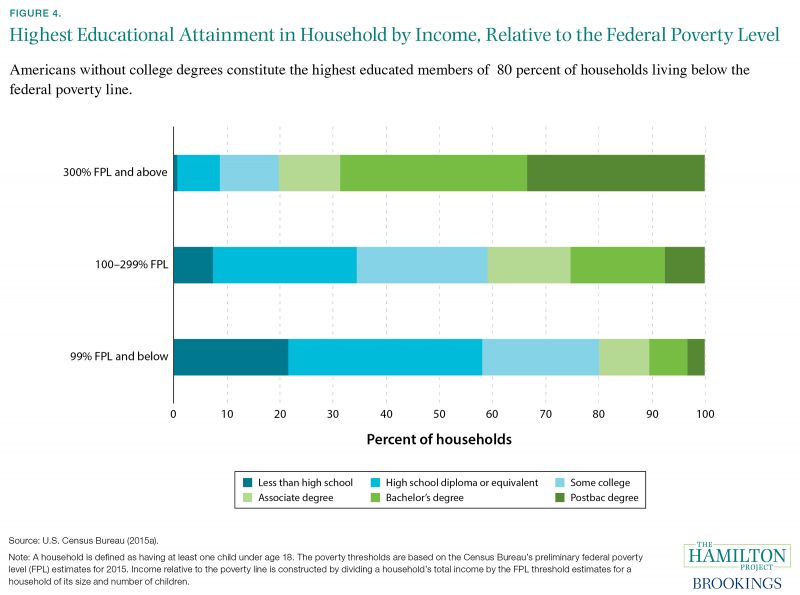

Fact 4: Americans who did not attend college form a larger share of those who live below the poverty line.

On average, more education decreases one’s likelihood of living in poverty. As shown in figure 4, the poorest Americans—with incomes below 100 percent of the federal poverty line, or below $24,000 for a family of four—are typically much less educated as measured by the highest educational attainment within the household. Fully one-fifth never finished high school, and over half have a high school diploma or less. Those with household incomes between 100 and 299 percent of the federal poverty line, or annual incomes between $24,000 and roughly $72,000 for a family of four, are much more educated: roughly four in ten have completed at least an associate degree, and only about one-third of them have a high school diploma or less. Among households earning 300 percent of the federal poverty line or more, over 90 percent have at least some college education. While education is a strong predictor of income, there is still considerable variation in education within income groups. For example, among households living below the poverty line, about 20 percent have at least one member who has completed an associate degree or more.

Shifts in the labor market help to explain the premium for college degrees. Workers lacking college degrees today are much more likely to be employed in low-wage, low-skilled occupations than were such workers in the past (Kearney, Hershbein, and Jácome 2015). For example, the share of working-age men without high school diplomas who were employed as operators and laborers—with median earnings of $25,500 in 2013—fell from 40 percent in 1990 to 34 percent in 2013. Meanwhile, the share working in food, cleaning, and grounds-keeping occupations—whose median earnings were $20,400 in 2013—almost doubled, from 11 to 21 percent.

Increasing one’s education is a good bet to increase one’s earnings. In an empirical simulation, Hershbein, Kearney, and Summers (2015) test what would happen to earnings if one-tenth of the men without a college degree were to obtain one. hey find that the decline in median earnings observed over the past three decades would be nearly erased, and earnings at the 25th percentile of the distribution would be 43 percent higher than they are today, thus helping to reduce inequality in the bottom half of the distribution.

Conditional on attaining a bachelor’s degree, the choice of what to study is also an important predictor of lifetime earnings. For the median graduate, total lifetime earnings range from close to $800,000 to more than $2 million depending on the major, as shown in a Hamilton Project economic analysis (Hershbein and Kearney 2014). Although there is substantial variation in earnings within majors, those that emphasize quantitative skills—such as engineering, computer science, economics, and finance—tend on average to have graduates with the highest lifetime earnings, while majors that train students to work with children or provide counseling services—such as early childhood education, elementary education, and social work—tend to have graduates with lower lifetime earnings. There is compelling evidence that effective teachers in early childhood impart large gains to society through their students’ subsequent gains in earnings and other life outcomes (Chetty et al. 2011). If low pay for teachers in early education dissuades potentially impactful workers from going into the field in the first place, the result could be costly to society in the long run.

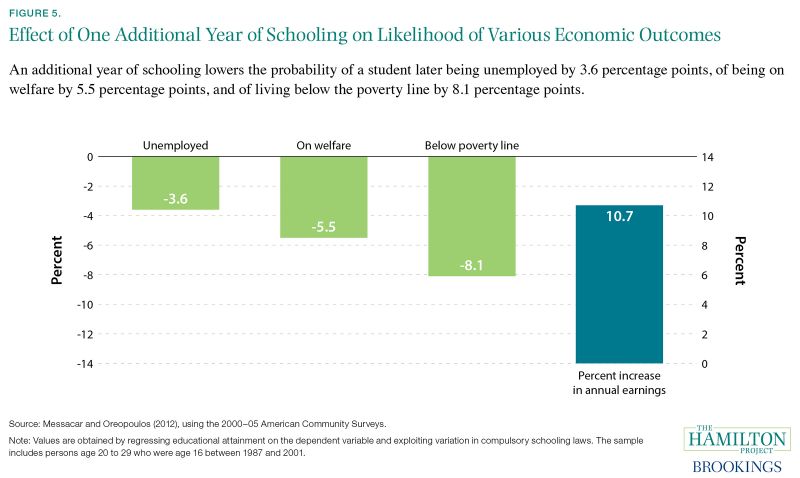

Fact 5: An additional year of schooling increases earnings and reduces the likelihood of an individual being unemployed, on welfare, or in poverty.

Measuring the direct effect of education on economic success is no straightforward task: not only does education improve skills, but students with higher skill levels are more likely to pursue further education. In other words, the education wage premium can be attributed partly to selection (the tendency that students who go on to college already have higher levels of cognitive and soft skills) and partly to treatment (the direct impact of additional years of schooling). As a result, it would be incorrect to infer that giving a college education to someone who would have otherwise obtained just a high school diploma would cause her earnings to increase by the size of the gap between high-school-educated and college-educated workers. However, research that isolates the causal impact of additional schooling does find that additional years of schooling improve outcomes.

To isolate the effects of educational attainment on earnings, Messacar and Oreopoulos (2012) take advantage of changes to state laws governing minimum school-leaving age. As shown in figure 5, one year of additional schooling lowers the probability of a student later being unemployed by 3.6 percentage points, of being on welfare by 5.5 percentage points, and of living below the poverty line by 8.1 percentage points. Among those working at least 25 hours per week, an additional year of compulsory schooling is associated with a 10.7 percent increase in annual earnings. These results may be understated because education earnings gaps tend to increase with age and these results focus only on younger cohorts.

Chapter 2: The K-12 System Faces Serious Challenges

Fact 6: The majority of U.S. public school students—over 27 million children—attend a high poverty school.

Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 provides federal funding to schools either through targeted assistance to low-income students, or through a schoolwide program if at least 40 percent of the school’s students qualify as low income (based on local criteria such as eligibility for the free or reduced-price school lunch program or receipt of means-tested family assistance through the Social Security Act or Medicaid) (§ 1113). The U.S. Department of Education (ED) classifies schools with 40 percent or more low-income students as high-poverty schools (Lippman, Burns, and McArthur 1996, 18). In 2014 a majority of students nationwide—56 percent—attended high-poverty schools. The state with the highest share of students attending high-poverty schools is Mississippi, at nearly 92 percent, and the state with the lowest share is Minnesota, at roughly 17 percent. As shown in figure 6, southern states tend to have the largest shares of students attending high-poverty schools.

School poverty concentrations are a strong predictor of school achievement averages (Kennedy, Jung, and Orland 1986; Murnane and Steele 2007), and concentrations of low-income students lead to a variety of challenges for a state’s public school systems. Research demonstrates that concentrations of low-income students are more expensive to educate across several dimensions (Downes and Pogue 1994; Duncombe and Yinger 2004). For example, schools with high shares of low-income students have higher teacher attrition rates due to difficult working conditions such as larger class sizes and lower-quality facilities (Greenlee and Brown 2009; Murnane and Steele 2007). Schools with high concentrations of poverty also face higher student turnover because low-income students tend to change schools more often (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES] 1996, figures 3.14). Title I of ESEA provides supplemental funding to school districts with large numbers or concentrations of low-income students.

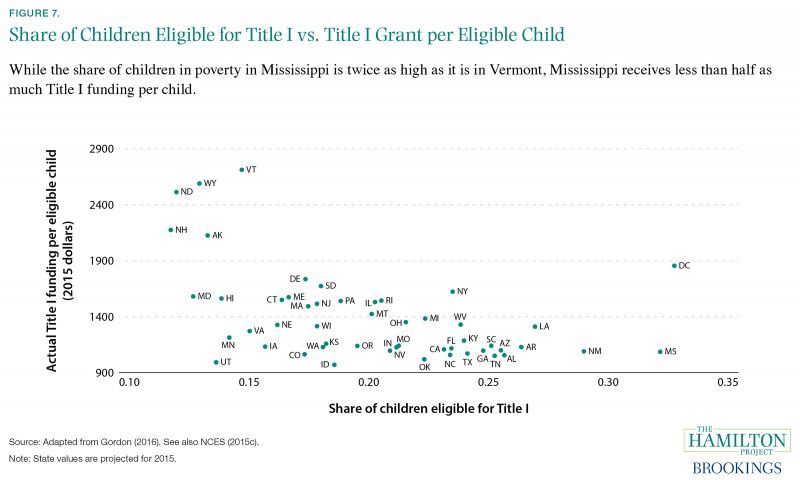

Fact 7: On average, states with higher concentrations of children in poverty receive less antipoverty (Title I) funding per child.

Title I of ESEA is the primary source of federal funding for schools with high concentrations of poverty. The purpose of Title I, particularly its schoolwide program, is to allocate more money to schools with concentrations of poverty. As discussed in Fact 8, low-income students are more likely to struggle in school and require additional support. However, the negative trend in figure 7 shows that states with higher shares of low-income students receive less Title I funding per eligible student. Because Title I is the primary mechanism for the federal government to distribute school funds across states, this negative relationship is counterintuitive and suggests that the funds may not be targeted appropriately in the status quo.

The negative relationship between share of students eligible and funding per eligible student is due in large part to the interaction between Title I’s chronic underfunding and the complex Title I formulas that distort allocations in the absence of full funding. For example, to fully fund the Basic Grants portion of Title I in 2015 would have required $50 billion in allocations; Congress instead appropriated only $6.5 billion. A new Hamilton Project policy proposal by Nora Gordon, “Increasing Targeting, Flexibility, and Transparency in Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act to Help Disadvantaged Students” (2016) discusses the causes of this dilemma and offers potential policy solutions. Gordon explains that a small state minimum leads to states such as Vermont receiving a disproportionate level of Title I funding. Additionally, a provision known as hold harmless, which allows districts to continue to receive allocations based on allocations received in previous years, prevents Title I funding from adapting quickly to structural changes in poverty levels across states and districts.

Fact 8: Average performance among low-income students declines as their population share increases.

High poverty concentrations pose a challenge, in part because average test scores among low-income students decline as the share of low-income students increases. The graph demonstrates that, on average, a 10 percentage point increase in the share of low-income students in a state predicts a 2.3 percentage point decrease in the share of low-income students scoring at or above proficient on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP); a proficient score indicates “solid academic performance,” positioned between the basic and advanced levels (NAEP 2015a). The national average for the share of low-income students scoring proficient or better is 18 percent, compared to 48 percent for the rest of the student population. In states with high concentrations of low-income students, this figure is as low as 7.4 percent.

However, some states with similar shares of low-income students have very different levels of proficiency. For example, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Jersey all have a share of low-income students that is just under 40 percent, but there is a difference of nearly 20 percentage points in the share of low-income students scoring at or above proficient. While it is difficult to directly compare school quality across states, Connecticut has a school finance formula that is heavily reliant on local property taxes—leading to more funding for schools in high-value areas—and has been noted as one of the states with the largest achievement gaps between high- and low-income students across a variety of measures (NAEP 2015b; Zimmer and Hodgson 2015).

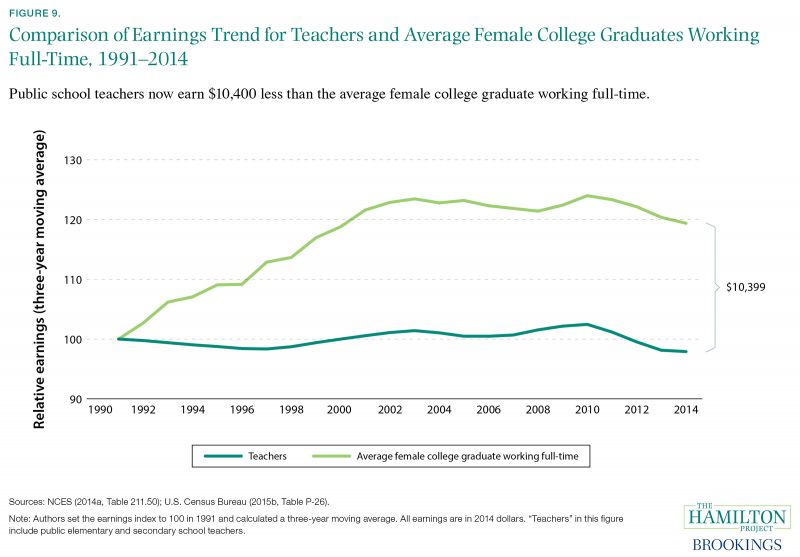

Fact 9: The salary of public school teachers has declined relative to other career options

Average earnings among women with college degrees have increased dramatically over the past 25 years. While the average female college graduate working full-time earned an inflation-adjusted $56,204 in 1993, by 2014 her earnings had grown almost 20 percent to $67,088. Teacher pay, on the other hand, has been stagnant over these years, dropping slightly from $58,048 to $56,689. As shown in figure 9, both college-educated women overall and school teachers in particular saw their wages decline through the Great Recession.

Although not all teachers are female, teaching remains the second-most popular occupation for women (U.S. Department of Labor [DOL] 2014), and three-quarters of public school teachers are female (NCES 2015a). As alternative labor market opportunities for women have expanded, teaching has become a relatively less attractive career path (Murnane and Steele 2007). The average starting salary for an education major in 2014 was $40,267, the only category to see a decline from the previous year (National Association of Colleges and Employers [NACE] 2014). This stands in stark contrast to 1960, when teachers earned on average 13 percent more than their fellow female college graduates, and even in contrast to 1980, when teachers earned 4 percent more (Hurley 2013).

Earlier work found that salary increases during the 1980s did not improve the quality of new teachers entering the profession (Ballou and Podgursky 1997). Since then, though, the accountability movement has realigned incentives so that schools today are more likely to be evaluated by student performance. As argued in Duncan and Murnane (2014), a well-designed accountability system can promote improvements in school practices, such as greater willingness to use resources and to work together in new ways to better promote students’skill development. As a result, salary increases may matter more today than they did in the past.

In a recent poll, 60 percent of undergraduate students reported some interest in a teaching career. When asked what policies might induce them to join the profession, the top responses included increasing pay for every teacher and, in particular, increasing pay for high-performing teachers (Hiler and Hatalsky 2014). The pay and prestige disincentives among the best and brightest to teach may pose an especially large problem for high-poverty schools, where work environment challenges associated with teaching in such schools, including lower parental engagement and leadership instability, further compound the opportunity costs to becoming a teacher (Simon and Johnson 2013). Emphasis on school accountability also increases pressure on teachers to improve student test scores and serves as a disincentive to working at a low-performing school (Murnane and Steele 2007). Among those who chose to teach directly after college, those who scored in the highest quarter on college entrance exams were less likely to be observed in the profession 10 years later than were those who scored in the lowest quarter; 13 percent of teachers reported leaving the profession altogether due to low pay (Alt and Henke 2007).

Fact 10: Spending on K-12 students varies substantially by state.

There is a large degree of variation in instructional spending across states. Instructional spending includes salaries and benefits for teachers, textbooks, supplies, and other purchased services for extra- and cocurricular activities (NCES 2012b). While schools in the Northeast spend $8,000 to $13,000 or more per student on instruction, schools in western and southern states typically spend much less (NCES 2012a). After adjusting for differences in living costs across regions (as proxied by variation in average earnings across states), the spending gaps narrow slightly but remain: northeastern states spend almost twice as much as western and southern states.

States predominantly rely on income and sales taxes for education funding, which can provide wealthier states more resources for education (Oliff and Leachman 2011). As a result of varying resources and preferences for education across states, a student in Vermont may receive as much as $95,000 more in instructional expenditures from kindergarten through 12th grade (adjusted for cost of living) than a student in Utah (NCES 2012a). Ensuring that students have equal access to a quality education across all states is a key rationale for federal involvement in school funding (Rentner 1999; ED 2012).

It is worth noting that spending also varies substantially within states and even within school districts (see Fact 11). The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015 introduced requirements to report school-level spending, which will bring unprecedented transparency to these spending differences.

Fact 11: Most education spending comes from state and local revenues.

Federal, state, and local education spending for public elementary and secondary schools totaled $620 billion in 2012, the most recent year for which data are available. Although the population of students has grown by 40 percent since 1960, per-pupil spending has increased by 274 percent (NCES 2014a). Federal education funds flow to states primarily through grant programs, such as funding for low-income students through Title I of ESEA and special education grants through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990. The federal role in funding education grew with the 2001 reauthorization of ESEA, known as the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, and temporarily increased further with the economic stimulus package in 2009 through additional grants for Title I and IDEA, along with State Fiscal Stabilization Fund grants for education (ED 2009). Despite increases in the federal share of spending, from 6 percent in 1990 to a peak of 13 percent in 2010 and back to 10 percent in 2012, the vast majority of school funding comes from state and local levels.

Local school funding is predominantly raised from property taxes, which make up 81 percent of total school revenue (NCES 2015c). Since wealthy families tend to live in affluent communities, increasing the tax base and revenues for local schools, their children’s per-student spending is typically higher in these districts than in poor districts. As a result, revenues raised for school spending can differ dramatically due to differences in property values and tax rates. In Texas, for example, the Fort Sam Houston school district receives only $265 in local revnue per student, while the neighboring Alamo Heights school district receives $13,007 in local revenue per student (NCES 2012a).

In cases where variations in property values lead to wide disparities in local revenue for educational spending, state and federal funds can serve to offset these differences. Beginning in the 1970s, many states have reformed their school finance systems to address this inequality. Often reacting to mandates from courts that found local finance systems unconstitutional, states have moved away from funding based primarily on property taxes and have implemented state aid formulas that direct more money to low-income and low-tax-base school districts (Lafortune, Rothstein, and Schanzenbach, 2016). Once state and federal spending are included in the example of Texas school districts above, the gaps are reduced dramatically: total revenues per student in Fort Sam Houston are $14,640, compared with $15,607 in Alamo Heights.

Chapter 3: Promising Approaches to Improve Educational Outcomes

Fact 12: Early childhood interventions can raise high school graduation rates.

On average, a black child entering kindergarten scores 0.66 standard deviations in math (and 0.40 in reading) below her white peers (Fryer and Levitt 2006). By comparison, the income achievement gap is even worse: upon entering kindergarten, the difference in scores between a child from a household in the 10th percentile of the income distribution and a child from a household in the 90th percentile was more than two times greater than the black–white achievement gap (Reardon 2011). Furthermore, the income achievement gap remains as the child advances through school (Reardon 2011).

The persistence of these gaps suggests that intervening early in life may have lasting benefits, and that a number of early-life interventions, as shown by figure 12, may help children to develop the foundational cognitive and emotional skills needed to successfully complete later milestones, such as high school graduation (Murnane 2013).

Three programs focused on preschool-aged children have substantially improved high school graduation rates, especially among students at greater risk of dropping out. Head Start, the federally funded program targeting poor children between the ages of three and five with preschool, health, and social services, increased high school graduation rates among recipients by up to 20 percentage points, depending on the cohort and demographic group studied (Deming 2009; Garces, Thomas, and Currie 2002; and Ludwig and Miller 2007). Head Start particularly benefited black and Hispanic males, increasing their high school graduation rates by 5.5 and 18.1 percentage points, respectively. Furthermore, it is estimated that the Perry Preschool intervention, which provided high-quality preschool to black children, had positive effects on a number of outcomes, including increased earnings and lower rates of crime among participants. Preschool attendees graduated high school at rates 20 percentage points higher than nonattendees (Schweinhart et al. 2005). Targeting somewhat older children, the Tennessee Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR) experiment investigated the effects of being assigned to a small class size from kindergarten through third grade (Chetty et al. 2011). Black and low-income males experienced particularly sizeable gains in high school graduation rates from assignment to smaller classes (Murnane 2013).

In addition, early-life interventions outside of school settings have been shown to increase high school graduation rates. Recent work on cohorts born in the 1960s and 1970s has shown that access to the Food Stamp Program from the time of a child’s conception through age five increased high school graduation rates by 18 percentage points (Hoynes, Schanzenbach, and Almond 2016). The success of these childhood programs points to the lasting benefits of intervening well before students enter high school.

Fact 13: Interventions for older children are not too late—interventions during high school also raise graduation rates.

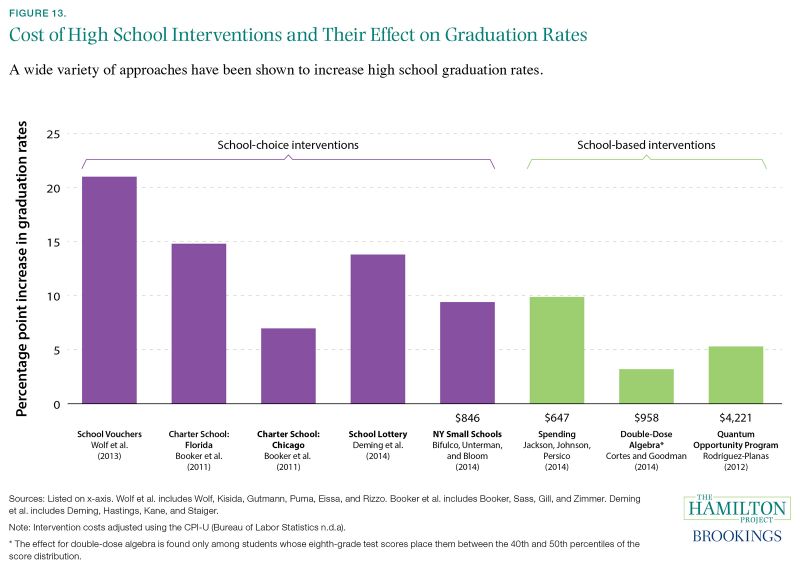

There is strong evidence that a variety of high school age interventions, most of them targeting students from low-income and minority backgrounds, have successfully increased high school graduation rates. Figure 13 graphs the percentage point increase in the high school graduation rate for several high school interventions, with the per-student net cost of the intervention displayed below the bars when applicable. Note that we do not mean to suggest that these are the only effective interventions, but instead that these are the interventions that have been rigorously evaluated.

Many of the interventions in the figure share the theme of expanded school choice (i.e., improving outcomes through the channel of where students go to school). They include school lotteries in Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Schools (which improved high school graduation rates by 14 percentage points), charter high schools in Florida and Chicago (7–15 percentage points), and the District of Columbia’s school voucher program (21 percentage points). Net costs for each of these interventions are hard to estimate, but are generally thought to be modest. New York’s small schools initiative has been successful in raising graduation rates (9 percentage points) particularly among black males (11 percentage points, or from 31 to 42 percent), a group that has historically had some of the lowest graduation rates (Bifulco, Unterman, and Bloom 2014). The additional cost per student per year of the small schools initiative was about $850, and falls to nearly zero when accounting for differences in teacher salaries and student populations (Unterman 2014).

Other interventions have focused on improving outcomes within schools. These interventions tend to be more limited in scope. Double-dose algebra, a program at Chicago Public Schools, requires students whose eighth grade math test scores place them below the national median to enroll in two algebra courses when they begin high school—regular algebra and an algebra support class (Cortes and Goodman 2014). At an estimated cost of less than $1,000 per student, students enrolled in the double-dose classes increased their graduation rates by 2.6 percentage points; however, these effects were only found for the highest-scoring students subject to the intervention, who scored just below the national median (Cortes and Goodman 2014). An intensive mentoring program at 11 high schools, most of them urban, has also improved graduation rates among low-performing youth (Rodríguez-Planas 2012).

An important recent paper documents the impact of court-ordered school finance reforms in the 1970s and 1980s on spending and subsequent student outcomes (Jackson, Johnson, and Persico 2016). A 10 percent increase in per-pupil spending during each year of schooling increases high school graduation rates by 10 percentage points. Although the additional funding was generally unrestricted, the study finds that school spending increases were associated with decreases in student-to-teacher ratios and increased teacher salaries.

Similar to the school choice interventions, it is difficult to extrapolate whether these programs would still be effective if they were more widely adopted both within and across school districts. Murnane (2013) highlights the central challenge facing education reformers: because of their limited scale, modest interventions—such as double-dose algebra—are more straightforward to implement and are easier to rigorously evaluate, but they do not address the underlying challenges facing less-advantaged students. Large-scale interventions, such as New York’s small schools initiative and some charter school models, may show some success at addressing the underlying challenges but are difficult to successfully replicate in other contexts. Improving the methods of evaluation and designing interventions for replicability are crucial to understanding what additional approaches work for improving high school graduation rates.

Fact 14: Several charter schools have been successful at raising student achievement, but gains are not universal.

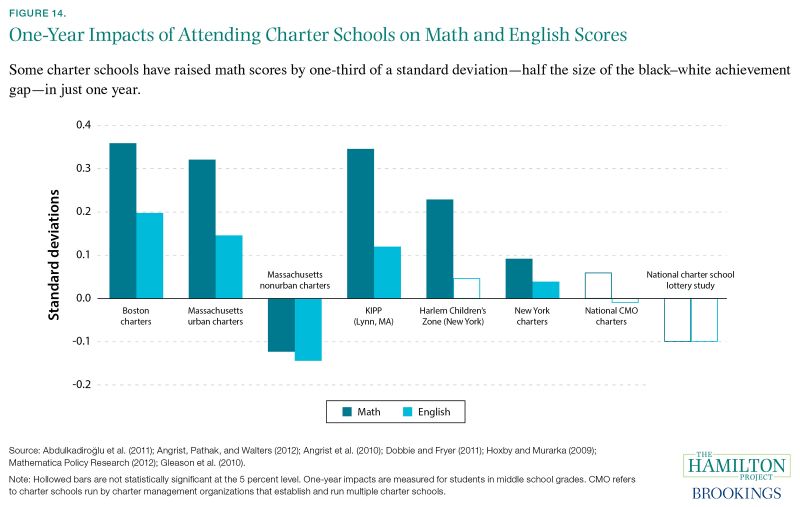

Charter school enrollment has grown steadily over the past two decades, from about 400,000 students (1 percent of the student population) in 2001 to 2.3 million (4.5 percent of the student population) in 2013 (NCES 2015b). Charter schools differ from traditional public schools because they are subject to fewer regulations and typically receive a fixed funding amount per pupil (though total expenditures per pupil vary due to philanthropic support). Charter schools have greater scope to innovate, employing a variety of methods, such as different curricula, alternative class schedules including longer school days and “Saturday school” to increase instructional time, high-dose tutoring, and other approaches (Angrist et al. 2010; Fryer 2012).

This new approach has yielded some success: many urban charter schools are able to significantly improve test scores in math and English in one year. As shown in figure 14, middle school students attending urban charter schools in Massachusetts and New York have increased their math scores by roughly one-tenth to one-third of a standard deviation relative to their peers who attended traditional public schools. Such gains are substantial: in the case of the Harlem Children’s Zone charter schools, if the same gains were achieved for three years it would be enough to eliminate the black–white achievement gap (Dobbie and Fryer 2011).

However, evaluations of charters at the national level show that, on average, charter schools perform no better than traditional schools (Gleason et al. 2010). In Massachusetts, for example, nonurban charter schools appear to reduce test scores, which may be due to differences in curriculum or student demographics (Angrist, Pathak, and Walters 2012). These results suggest charter school expansion should be considered carefully, factoring in the composition and needs of the district’s student population, as well as the relative success of some charter school models over others.

Related Content

Brad Hershbein, Melissa S. Kearney, Lawrence H. Summers

March 31, 2015

Michael Greenstone, Adam Looney, Jeremy Patashnik, and Muxin Yu, The Hamilton Project

June 26, 2013

Isabel V. Sawhill, Jeffrey Tebbs, William T. Dickens

April 30, 2006

Related Books

Zia Qureshi, Daehee Jeong

November 1, 2024

Jaganath Sankaran

October 24, 2024

Todd Stern

October 8, 2024