After a decade and a half of being involved in large-scale military operations in the Middle East and South Asia, the United States is increasingly looking for ways to pursue its security interests with minimal involvement. This shift—a key hallmark of the outgoing Obama administration—is unlikely to change under the administration of Donald Trump. The number and complexity of military conflicts burning in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia make large-scale military involvement very costly. Yet allowing for large territories around the world to disintegrate into brutal conflicts—or be dominated by terrorist groups threatening the United States and its allies—may also be highly detrimental to U.S. interests.

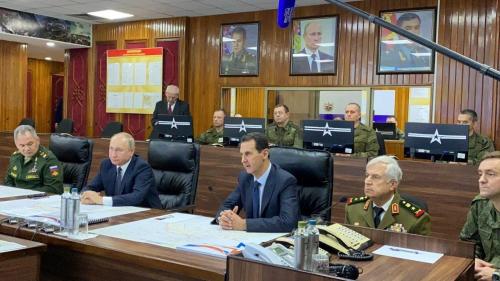

The Obama administration thus embraced a strategy of building up the capacities of partners in such conflicts—preferably, those of national governments. But when national forces prove insufficient, unable, or unwilling to defeat the threat—such as in Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, and Somalia—the United States has to decide whether to support (or establish) local militia and other irregular forces. Indeed, militias are likely to stay in vogue as a tool of U.S. security policy, given the individuals President-elect Donald Trump is considering as key national security and foreign policy principals.

Fleeting convergence

Building partner capacity and standing up militias may at times turn out to be the least bad of available policy options. The two approaches are not identical: Building up the official forces of a country allows for greater levels of host-nation accountability to donors and to their domestic population than standing up irregular forces. Building up official partner capacity is thus clearly preferable to embracing militias.

Nonetheless, both policies need to be adopted with a clear understanding of how limited their contribution will be to the prosecution of U.S. interests. Despite the seductive promise that in situations of limited U.S. engagement, others will do for the United States what it is not willing to do for itself, a robust alignment of U.S. interests with those of its presumed partners will often be lacking.

Instead of a robust alignment—and a joint strategy for how to build stable and legitimate political order—the United States and its presumed partner might often enjoy only a momentary intersection of interests. A divergence of interests is likely to arise quickly during intense and fluid conflict situations, but also when conflict subsides and the government’s survival is no longer threatened. The United States could thus rapidly find its partners unreliable and pursuing policies directly contradictory to its own. Partner governments may well pocket U.S. assistance and undertake only the bare minimum policy to keep U.S. resources flowing—while at the same time striking their own deals and accommodations, hedging their bets, or targeting their own enemies, not those of the United States. Even when militias seem to be defeating the enemy du jour, they will have a tendency to go rogue and themselves become one of the deep-seated drivers of conflict.

[T]he United States and its presumed partner might often enjoy only a momentary intersection of interests.

What to do?

Does this imply that the United States should not engage in building up capacities of presumed partner governments and standing up militia forces? That needs to be decided on a case by case basis, and one of the criteria needs to be an in-depth consideration of when and how these presumed partners will defect from U.S. objectives and undertake actions inconsistent with U.S. interests. Policy evaluations need to consider what kind of restraint and rollback capacity of these presumed partners—whether the state or militias—the United States will have when interests diverge, as well as what kind of actions the United States could take to mitigate the negative impacts on U.S. interests and values.

To the extent that the United States does provide security assistance to a new “partner,” it should primarily seek to engage formal military and police forces. They can presumably be more accountable to the United States—as well as, and no less importantly, to local populations. Such security assistance is also more easily consistent with future stabilization and state-building efforts than supporting non-state militias.

Particularly in the case of militias, the presumption for U.S. policy should be not to stand them up. Nonetheless, if supporting militia forces is the least bad option—such as because formal military and police forces are totally corrupt, abusive, collapsed, or antagonistic to the United States—the United States needs, from the very beginning, to build into its militia effort a plan for how to roll them back. Merely defunding the militias is not enough: Cutting them off from funds without dismantling them is only likely to encourage them to engage in predation on local communities or sign up with U.S. enemies willing to pay them, perhaps even the very ones they fought before with U.S. money.

It’s also important to have nuanced intelligence and a broad understanding of the multiple political impacts the militias and the rollback processes have. If such restraint mechanisms are elusive (which will often be the case in many situations of intense conflict with dangerous terrorist groups and miserable governance by official state actors), the United States needs to realize that its embrace of militias will merely defer immediate threats to later and long-term problems, even compound them. Our friendly militias today will likely end up a threat to our interests in a matter of time.

Our friendly militias today will likely end up a threat to our interests in a matter of time.

Assessments of the chances of success thus need to be much broader than merely eliminating a particular terrorist group. They also need to include judgement of whether a sufficiently stable, sustainable, and legitimate order and governance will ensue, or whether supporting “partners” merely perpetuates structural causes of instability.

Upholding human rights restrictions in deciding to whom U.S. security assistance can be provided—such as embodied in the Leahy Amendment—is important. It is crucial not only because of U.S. values and humanitarian interests; it’s important because such assessments of eligibility are a good indication of whether U.S. assistance will be effective, or end up supporting an actor whose rapacious, predatory behavior ultimately fuels a cycle of instability and keeps the United States stuck in a mire—even if via a proxy.

Finally, the United States need to recognize that providing security assistance, building up partner capacity, or standing up militias are not merely technical endeavors or tactical military tools. They are all profoundly political undertakings, with potentially large impacts on power distribution and political arrangements in recipient countries. All such efforts by the United States thus need to be linked to a larger U.S. political strategy of how to create sustainable structures of stability and order, backed up by sufficient and sustainable resources and legitimacy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Fleeting convergence: Building partner capacity and militias

December 6, 2016