Five years ago, early in the summer of 2011, Itzik Arlov—an Israeli from the ultra-orthodox city Bnai Brak—used his Facebook page to complain about the rising price of cottage cheese in the country. His post went viral. It ignited a protest movement, with middle-income citizens demanding “social justice” from the government. Led by students and young professionals, Israelis took the protest to the streets.

For decades, Israel’s middle class—which carried a significantly larger burden than other sectors in terms of labor force participation, military service, and tax contributions—was silent about its economic struggles. That time ended that summer. During that summer, hundreds of working-class citizens who struggled to afford housing pitched tents along the streets of Tel Aviv and lived in them for weeks, even months. That September, about half a million Israelis (over 6 percent of the country’s total population) marched in the streets to make their voices heard, demanding solutions to reduce the cost of living, and of housing in particular.

These protests defined Israeli politics in the years to come. Ever since, most political parties in Israel shifted their electoral platforms from peace (or lack of it) to economics. Since 2011, the rising stars of Israeli politics have been either former leaders of the social movement or those who have been able to transform the predominant discontent into votes in national elections.

Five years later, what has changed?

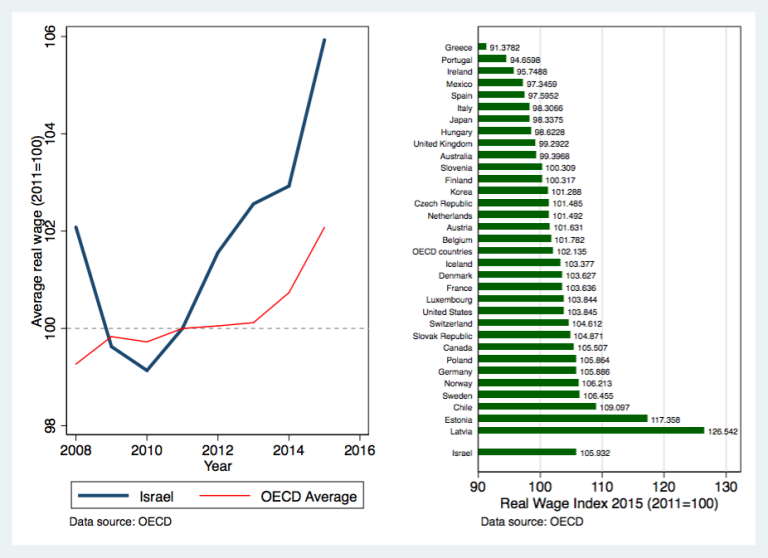

Over the past five years, there have been a number of hopeful developments. By 2015, the real wage—a measure of purchasing power—of Israelis was about 6 percent larger than in 2011 (see Figure 1, left panel). The growth in real wages has been large compared to the average growth in real wages among OECD countries, which grew only by about 2 percent since 2011. In fact, as compared to its OECD peers, Israel is among the top performers in terms real wage growth since 2011 (see Figure 1, right panel).

Figure 1 – Real wage index (average) in Israel and OECD

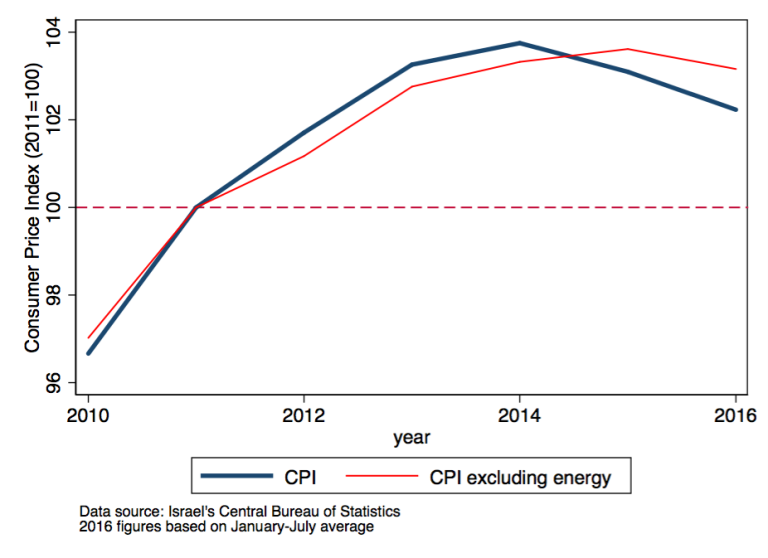

Real wages have grown because nominal wages have risen faster than prices. As Israel’s unemployment rate has declined over the past few years to a historic low, average nominal wages have increased. The government has also recently increased the minimum wage by about 10 percent, and it is expected to increase it by another 15 percent by the end of 2017. As the blue line in Figure 2 shows, inflation slowed down after 2012 and prices even dropped since 2014.

Figure 2 – Israel’s Consumer Price Index

Is this decline in prices a result of policy? Perhaps. Bank Israel, the nation’s central bank, has played an important role in managing inflation successfully. In addition, price levels might have responded to numerous actions by both the executive and the Knesset aimed at increasing competition in the telecommunications sector and lowering barriers to imports in other industries. Yet, global conditions and measurement peculiarities also play a very important role in driving these changes.

First, as Figure 2 suggests, the global fall in oil prices partly explains the slowdown and decline in prices in Israel (since the price index excluding energy costs, the red line, becomes larger than the overall index, the blue line, after 2014). This phenomenon can explain the sharp increase in Israelis’ real wages over the same period shown in Figure 1. Therefore, if oil prices increase again, real wages would probably drop, reversing recent trends.

Second, only housing rent costs—and not ownership prices—are used to compute Israel’s Consumer Price Index, and with it real wages figures. While costs for housing services have increased by about 13 percent since 2011 (according to data from Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics), housing ownership prices in Israel have increased, on average, by almost 30 percent.

High prices across all sectors of the Israeli economy are a systematic problem that relates to lack of competition and often excessive bureaucracy.

Thus, the increase in real wages and slowdown in the rise of prices in the past several years might have been overestimated and are not a sign that deep reforms are no longer needed. High prices across all sectors of the Israeli economy are a systematic problem that relates to lack of competition and often excessive bureaucracy. In the housing sector, for example, it takes about 13 years, on average, for new construction to be completed, contributing to the problem of under-supply. But there is no way around it. Housing costs will only drop if supply is expanded. Past and current attempts by government and opposition parties alike to reduce prices by cutting real estate value-added taxes or to create public housing are ineffective because they would increase demand, not supply. More generally, beyond housing, policies that aim to control prices are ineffective and have failed miserably in the past.

Looking forward

There is no doubt that Israel has a strong economy, and it has remained strong in spite of its reliance on volatile export markets and its particular security situation. Yet, beyond the cost of living, the country faces other challenges that could keep the economy from thriving at its full potential. Labor force participation is highly uneven across different demographic groups, for instance. While these groups’ participation in the workforce has sharply increased in the past few years (i.e. Arab women and ultra-orthodox men), the middle class still carries the bulk of the tax-paying burden.

Moreover, while innovation—fueled by the largest investment in R&D as share of gross domestic product in the world—has been a key engine of the Israeli economy in the past few years, some fear its benefits are not always enjoyed by those outside the startup scene. Israeli high-tech firms, which are typically highly funded by the government (and thus, taxpayers), are often acquired in early stages by larger foreign companies, generating fortunes for a few and almost no jobs at home. Thus, while innovation should definitely remain a priority in the national agenda, it is important to acknowledge that not all Israelis have been equally benefiting from the economic success of the “startup revolution.”

Last but not least, the occupation of West Bank and Gaza represent an important additional burden on taxpayers, who pay not only for large military expenses, but also subsidize the provision of public goods, housing, and other services to a minority of Israelis living beyond the green line.

Thus, while the data suggests some progress, there is still a lot of room for structural improvement before working-class Israelis can feel better off. Cost of living in Israel still remains among the highest in the OECD, productivity levels have declined as compared to its peers, and income inequality remains particularly high among OECD countries. That is why, after five years, in spite of some progress, most of the protesters that lived in tents in the summer of 2011 would still say that what they demanded hasn’t yet been achieved. They might well be right.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Five years after the social protests in Israel, what has changed?

August 1, 2016