Editor’s Note: On October 2, 2014 the Brookings Global-CERES Economic and Social Policy in Latin America Initiative (ESPLA) launched the

2014 Latin America Macroeconomic Outlook report: “Macroeconomic Vulnerabilities in an Uncertain World: One Region, Three Latin Americas.”

The five graphs below elucidate the major findings of the report.

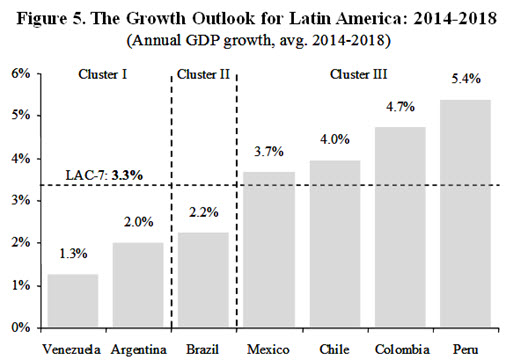

After a decade of high growth and high expectations about the region’s future, the new and less complacent global context implies a return to lackluster growth rates of 3.3 percent over the next five years, from 2014 to 2018. Such a reduction in the cruising speed of the region comes as a result of the change in outlook for growth in advanced economies (mired in what has been called “secular stagnation”); the imminent end to China’s investment-led, credit-propelled growth model and further slowdown in its economy; softening commodity prices; and a gradual increase in the cost of international financing for emerging markets.

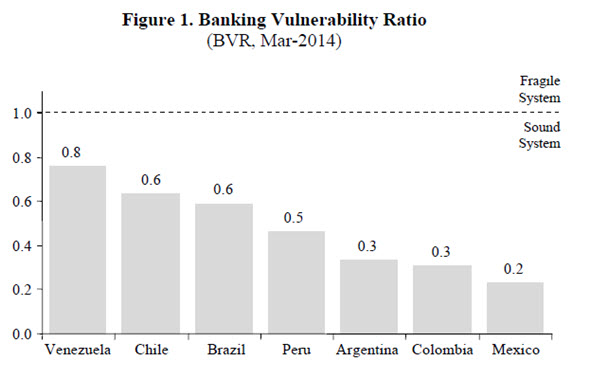

What are the macroeconomic challenges that lie ahead for the region? To answer this question we have constructed a series of indicators that are comparable across countries. Every indicator is normalized so that whenever the value is below 1 it denotes a positive outlook and when the value is above 1 it denotes a negative outlook in each macroeconomic dimension.

What emerges is a not a narrative of one Latin America, but of three: one with sound macroeconomic fundamentals (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru), one with weak fundamentals (Argentina and Venezuela), and one with mixed fundamentals (Brazil). Each cluster faces a different outlook and different policy challenges.

Source: Own calculations based on the IMF Financial Soundness Indicators and national statistics for Venezuela.

After a string of banking crises, debt restructurings and financial distress, the health of the financial system in the region has improved significantly. Clearly, the tightening of the regulation and supervision of the region’s banking systems during the last decade appears to have paid off.

In order to assess the banking outlook, we developed a Banking Vulnerability Ratio defined as the ratio of projected nonperforming loans under more adverse economic conditions—higher interest rates, lower growth and depreciating currencies—to maximum nonperforming loans (defined as the level of non-performing loans that would exhaust existing loan-loss provisions and bank capital). Surprisingly, the Banking Vulnerability Ratio is below 1 for each and every country in the region, meaning that if we rule out extreme events, banks in the region are in a strong position to endure a deterioration in economic conditions. From a macroeconomic perspective, this time around the weak link does not appear to be the banking system.

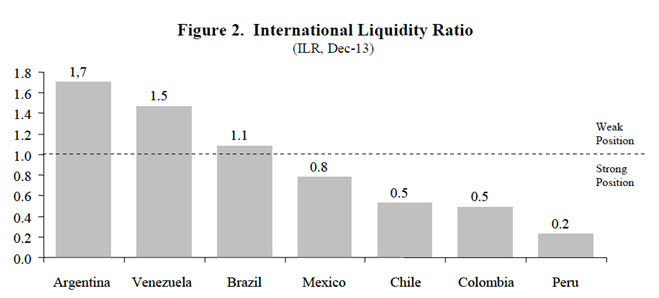

Source: Own calculations based on national statistics, IMF, IADB, CAF and FLAR.

Since the beginning of the cooling-off period in mid-2011, there has been a sharp contrast in the behavior of international reserves between countries with full access and those with limited access to international financial markets. While they have continued to increase in the former (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru), they declined significantly in the latter (Argentina and Venezuela).

To assess the international liquidity position we developed the International Liquidity Ratio. The International Liquidity Ratio is defined as the ratio of short-term debt obligations of the public sector—both domestic and external and including the stock of central bank sterilization instruments—and short-term external debt obligations of the corporate non-financial private sector due in the next 12 months to international reserves, plus the already agreed ex-ante contingent credit lines and potential credit lines that could be negotiated with multilateral or regional financial institutions.

We find that the countries in the first cluster—Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru—have a strong liquidity position which provides them with an effective cushion to weather episodes of financial turbulence in international capital markets, while Argentina and Venezuela have a very weak international liquidity position. Brazil is in an intermediate, borderline position.

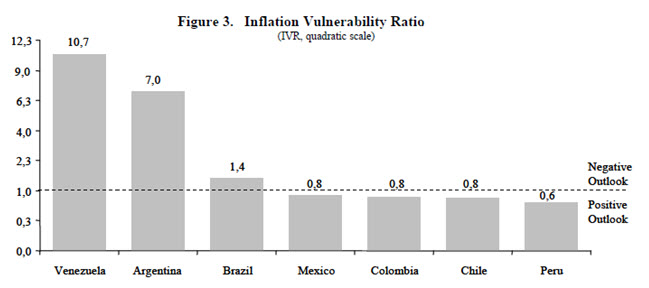

Source: National statistics and private sector estimations for Argentina. Forecasts are obtained from FocusEconomics and Econviews for Argentina.

In order to assess the inflation outlook, we consider a country to have a positive (negative) outlook for inflation if it is expected to remain or fall below (rise above) 4 percent in the next three years. With this definition, we developed an Inflation Vulnerability Ratio, defined as the ratio of projected inflation at the end of 2016 to a 4 percent inflation threshold.

Once again, a heterogeneous picture arises in which some countries have a very negative inflation outlook (Argentina and Venezuela) and face the need to make substantial policy adjustments, while some others have an extraordinarily strong and sustained track record of very low and relatively stable inflation rates (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru). Brazil misses the mark by a relatively small margin.

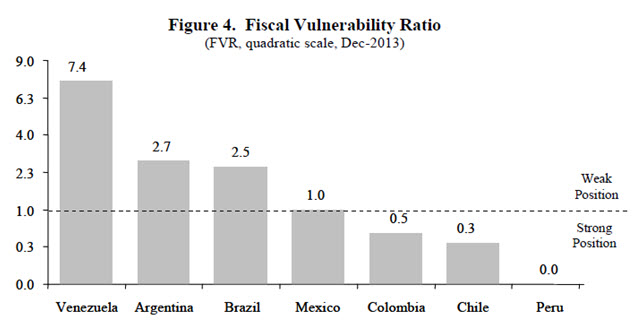

Source: Own calculations based on national statistics and IMF World Economic Outlook.

To evaluate the strength of the fiscal position we developed a Fiscal Vulnerability Ratio. The Fiscal Vulnerability Ratio is defined as the ratio of projected debt to GDP over 15 years (assuming identical inflation tax revenues for every country) to a 50 percent debt to GDP threshold.

A very diverse picture emerges between countries with very vulnerable fiscal positions (Argentina and Venezuela) facing the need to make substantial policy adjustments to stabilize the dynamics of public debt, while others are safely below the critical level of 1 (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) displaying extraordinarily strong fiscal positions. Brazil starts out with relatively high levels of public debt and displays a non-convergent debt dynamics that will require timely adjustments to public finances to preserve its current credit standing.

Source: FocusEconomics.

When assessing overall macroeconomic vulnerability, the region clusters into 3 groups. One group is composed of Chile, Colombia, Peru and Mexico—countries with full access to international markets and multilateral financing and strong macroeconomic fundamentals. Another group is composed of Argentina and Venezuela—countries with limited access to international financial markets and multilateral financing and weak economic fundamentals. Finally, Brazil belongs to the final and intermediate group, with full access to international financial markets and multilateral financing, yet displaying vulnerabilities in some macroeconomic dimensions—especially on the fiscal front. Notably, the growth outlook for the five-year period 2014-2018 according to market consensus forecasts clusters these seven countries into the same three groups (see Figure 5).

The magnitude of macroeconomic challenges will depend on whether the countries belong to a cluster with strong, mixed or weak macroeconomic fundamentals. For the countries with strong macroeconomic fundamentals (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) the key challenge is to consolidate macroeconomic stability in more trying times. For the countries with weak macroeconomic fundamentals, the need is to urgently restore confidence to stop capital outflows and the drain on international reserves, and to resuscitate their ailing economies. For Brazil, with mixed macroeconomic fundamentals, the challenge is to react in a timely fashion on the fiscal front to avoid compromising its current credit standing.

From a development perspective, pro-growth reforms will be needed in every country in the region—those with strong and weak macroeconomic fundamentals—to revitalize what otherwise will be a lackluster growth performance in the years to come. More adverse conditions may provide the right incentives for precisely that, for those are the times when politically complex decisions are usually made.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Five Charts to Explain Latin America’s Macroeconomic Outlook

October 8, 2014