Executive Summary

In December 2014, then Secretary of Education Arnie Duncan announced that $226 million had been awarded to 18 states under the Preschool Development Grants (PDG) program. Duncan said that expanding access to high quality preschool programs was critically important, and that the states receiving funding would serve as a model for others. The goal for these programs is to close the “opportunity gap.” However, no part of the $226 million included an independent and objective evaluation of the variety of programs states implement or their short- or long-term effectiveness. This paper reports on the dangers of continuing to implement an elementary school-based program in terms of its likely longer term effects and advocates for a serious evaluation of this policy so that it does not have the same fate as others that have been tried.

Under “Purpose,” the U.S. Department of Education’s Preschool Development Grants (PDG) website says:

The Preschool Development Grants competition supports States to (1) build or enhance a preschool program infrastructure that would enable the delivery of high-quality preschool services to children, and (2) expand high-quality preschool programs in targeted communities that would serve as models for expanding preschool to all 4-year-olds from low- and moderate-income families. These grants would lay the groundwork to ensure that more States are ready to participate in the Preschool for All formula grant initiative proposed by the Administration.[i]

The PDG program is slated for an increase in funding to $250 million per year in the new version of the federal education budget, not yet adopted.[ii] The current (and proposed) funding is being funneled through state education agencies and therefore primarily supports a dramatic increase in the number of prekindergarten classrooms housed in public elementary schools. This paper presents some concerns about that direction.

Within this short statement of purpose are many deep, implicit, and untested assumptions. The first is that education agencies in states and local districts know how to create a quality program for young children from high-stress, low-income families. In fact, there is little evidence that statewide implemented programs are even similar to each other across states, much less of high quality.[iii]

The second supposition is that the newly funded programs can serve as a model for expanding preschool to all 4-year-olds. The term “model” is used casually by many in the education field. If the new pre-K programs are truly to serve as models for others, that presumes that they will be evaluated, revised, and continuously improved until a valid form of the program exists for replication by others.[iv]

Yet, this program, on which millions are currently being spent and millions more are proposed has almost no evaluation connected to it and none that could be combined into an overall assessment of the program’s effectiveness.

When the PDGs were first announced, no independent, national evaluation was proposed at the same time from the same funding. Unfortunately, like many popular ideas in policy, there was a rush to implement with no accompanying concern for learning from the process, despite the real need for information.

Expanding pre-K programs presented the ideal opportunity to collect more rigorous information about the variety of programs states are implementing and to compare their relative effectiveness. Short-term effectiveness is important, but critical to the endeavor to help poor children succeed would have been an evaluation that includes tracking children into schools at least through the early grades.

One of the reasons there is no independent national PDG evaluation may be that advocates have convinced policymakers that both short- and long-term positive effects will accrue from the expansion, and that the field already knows how to design and implement “high quality” programs. Moreover, they have convinced policymakers that there is urgency to the expansion because of the increasing numbers of poor children in the U.S. and because of the recognized income-related achievement gap.[v]

Evidence from the only two experimental, large-scale evaluations of early childhood programs has demonstrated short-term gains for children that either fade immediately or eventually favor the comparison group.[vi] There may be hesitation among advocates about what the results of a rigorous and independent evaluation of PDG might be and the peril similar results to the earlier studies might present to the initiative.

Instead of awarding the task to an independent evaluator, evaluation was left up to each state and was rolled into its “state-level infrastructure” that in total could be no more than 5 percent of the overall budget. This infrastructure includes all the state personnel and accompanying expenses needed to implement and monitor the program as well as some unspecified evaluation.

States do not have to use the same evaluation instruments. They are supposed to provide both child and classroom assessments, but what they do can vary and as a consequence will be impossible to combine into an overall evaluation of the program. There is a technical assistance website for PDG grantees.[vii] On that page there is a link to the Center on Enhancing Early Learning Outcomes (CEELO). CEELO provided a webinar to recipients in March 2014 on quality improvement and program evaluation.[viii] It was very general but indicated that the states should be using whatever data they collect as “impact evaluation” and feeding the findings back to improve the program. But an impact evaluation has as its central question whether the outcomes experienced by participants in a program would have been the same if they had not been participants. This is a far cry from using whatever data are collected for efforts at program improvement.

In June 2015, CEELO issued a document providing background to states on conducting evaluations of the program.[ix] In this document, states were advised to measure classroom quality with the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-3 and the Classroom Assessment Scoring System along with two other less well-known measures. Neither of these instruments has been shown to be strongly related to children’s outcomes over the pre-K year[x] or to predict longer-term outcomes for children.[xi] Moreover, states were not advised who should collect the information, or how often or what training verification should be required.

In Tennessee, the Peabody Research Institute (PRI) is the PDG evaluator. In addition, PRI has been conducting a rigorous evaluation of the state’s scaled up pre-K program since 2009. PRI has reported results from one part of that work.[xii] Another component of the study involved classroom quality assessments of 155 pre-K classrooms chosen to be representative of the state’s program as a whole. These classrooms come from all over the state, are rural and urban, some with a long history of pre-K involvement and others less so, etc. These are not always the same classrooms as the ones involved in the longitudinal follow-up, as those classrooms were eligible for the study only if they were oversubscribed, but the data on practices were collected at the same time as the evaluation of the effects of the program on child outcomes. These observed classrooms represent the statewide program being implemented.

The new PDG classrooms are only in Nashville and Shelby County. The classroom observation instrument in both the state and PDG classrooms has been the same.[xiii] Observers stay in the classroom for the full day, from before children arrive until the last child leaves. The system provides, among other things, a summary of the way time is spent across the day. Thus the way time is being spent in the 139 PDG classrooms can be compared to the allocation of time in the statewide program (155 classrooms) of a couple of years ago, whose long-term effects are known.

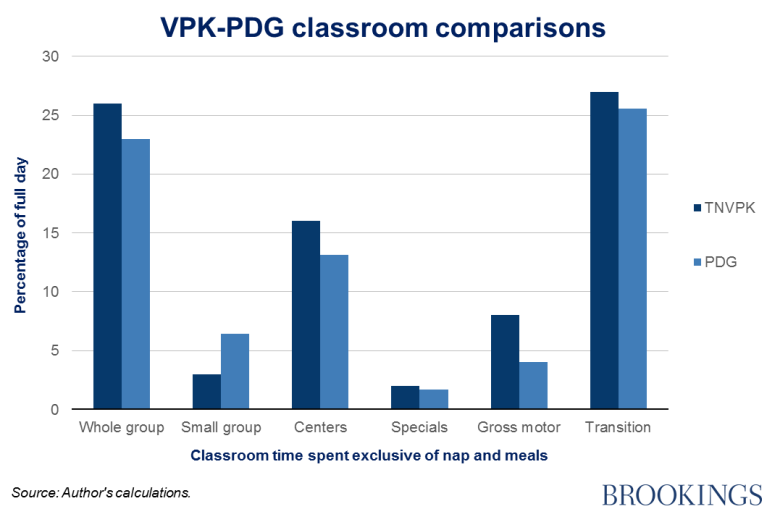

The chart below presents data comparing the two sets of classrooms, the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K Program (TNVPK) and PDG, in terms of the major pedagogical strategies observed in each.

Several things are of note:

- The most common instructional strategy used in both sets of classrooms is whole group instruction. Whole group instruction most often involves didactic instruction from the teacher to the entire group of children.

- Small group instruction occurs relatively infrequently even though these classrooms all meet the minimum requirements of having a group size of 20 or fewer and including both a licensed teacher and an assistant.

- The formerly most common instructional practice in early childhood classrooms, centers or free choice time, occurred a little more than half the amount of time that whole group instruction did.

- Very little time was spent outside on a playground or inside a gym (gross motor activity); many classrooms did not go outside or to the gym at all for the 6-8 hours the classroom was in session.

- Specials are relatively new to early childhood classrooms, a product of being in elementary schools. Specials most often involve children leaving the classroom to go to an enrichment activity—library, art, computer lab—taught by a different teacher. Some classrooms engaged in this activity a lot, others not at all, which accounts for the overall low percentage of time.

- What is most evident, of course, is that the most common activity found in both sets of classrooms was transition, moving children from activity to activity with no learning opportunity during that time.

It is important to note that the average Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS) score for the TNVPK classrooms was 4.2, which compares favorably with another statewide program in Georgia recently observed, whose average ECERS score was 3.7.[xiv]

Why do the classrooms look like this and what might account for the remarkable similarity in the division of time in the state pre-K classrooms and the new PDG funded classrooms? One possibility is the consequences of putting pre-K classrooms into public schools that were not set up to house them. As pre-K funding is increasingly located in the state education system, the danger is that pre-K may become just another grade level below kindergarten. A different viewpoint is for the development of 4-5 year olds to be considered as the culmination of the 0-5 developmental process with the outcome being the transition to formal education at age 5 (an age younger, actually, than the age at which many other developed countries begin formal schooling).

Whole group instruction has become more typical of kindergarten than in the past[xv] and appears to be trickling down into the pre-K classrooms. In fact, it is very difficult for early childhood teachers to hold on to practices they may know are better in the face of a whole school following a different approach.

Possible reasons for the large amount of time spent in transitions are important to consider. In elementary schools not set up for young children, the bathrooms can be down the hall, requiring children to leave their rooms, walk without disturbing others to the bathroom, and remain, again quietly, lined up outside the bathrooms for everyone to have a turn. Similarly, young children can be required to use the school’s cafeteria, another facility not set up for them. Time is required again to line up and walk quietly to the cafeteria and not infrequently to remain quiet throughout the meal. Another consequence perhaps of being in unsuitable school buildings is the lack of outside time. Schools often do not have appropriate or safe playgrounds for four-year-olds.

Of course, some of these issues can be addressed. While this may slow down implementation, policies could be adopted that allow pre-K classrooms only to be placed in elementary schools that can actually accommodate the needs of children that young. School districts could be required to serve meals in the children’s classrooms. Even if the bathroom is down the hall, teachers could be taught to take half their children at a time while the other half is reading a story, and so forth. But the issue is that none of the requirements for program monitoring and classroom quality include these features. It could be that those implementing the program believe that anything is better than nothing.

But all of these things together may not affect the amount of didactic instruction children are experiencing. What we have observed in the classrooms suggests a particular vision for what should be happening to the children served by PDG. The vision seems to consist of a dominating focus on teacher-directed instruction, with little time for children to construct learning themselves from independent activities, and no time at all to play. Education appears to be a serious business, better started young, especially for children from low-income families. This approach is supported by assumptions about what poor children are experiencing in their families: “Even a lower-quality preschool program can have an impact on children from the most disadvantaged environments,” a debatable assumption at best. [xvi]

This vision for what children need in their pre-K classrooms has been longitudinally tested. There is strong experimental evidence from our evaluation of the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K Program that the long-term effects of an early childhood program with a heavy reliance on whole group instruction and much time spent in transitions are not positive. By the 2nd grade, children who were income eligible and who wanted to enroll in pre-K but could not get into the program for lack of space (and who primarily stayed home) were out performing the pre-K children on measures of achievement and were viewed similarly by their teachers.[xvii] Why should different outcomes be expected from the PDG program when their classrooms look so similar? If the treatment is the same, aren’t the outcomes likely to be similar?

Pre-K expansion and Head Start collectively are like having a hammer—with the consequence that every problem is then perceived as a nail. For example, the terrible situation in Flint, Michigan where young children were exposed to lead in the drinking water, lead being a toxin that never leaves the body with horrifying cognitive consequences. The solution proposed in Flint was to increase the Head Start funding,[xviii] despite the fact that the Centers for Disease Control concluded definitively “there are no studies that specifically examine the impact of early childhood educational interventions on cognitive or behavioral outcomes for children who have been exposed to lead.[xix] No one seemed to know what else to do.

A public school classroom delivery system is not an absolute requirement. A recent debate in Minnesota was won by proponents of scholarships for low-income families to purchase care in the marketplace,[xx] a system that the National Institute for Early Education Research does not count as a state pre-K initiative.[xxi] In North Carolina, Smart Start, begun by Governor James Hunt in the early 1990s, did not focus on classrooms. Instead, funding was allocated to counties to create higher quality and seamless services for children aged 0-5 within the county, left up to the counties to determine.[xxii] More at Four was another North Carolina program begun in 2001 that focuses on four-year-olds but the children can be served in public schools, child care centers, and Head Start programs so long as the programs meet certain requirements.[xxiii] But these alternatives are losing ground to the push for pre-K programs to be overseen by education agencies and thus housed predominately in elementary schools.

As Sal Dominco, a Massachusetts state senator, said, “Who’s going to say they don’t support preschool? No one is going to say they don’t support it. We should be saying at what level do you support it? That’s the more important question.”[xxiv] It has become blasphemous to even raise reasonable questions about the design and effectiveness of preschool programs.

State pre-K, like Head Start, is a program with many staunch advocates and no reliable data demonstrating long-term positive effects. And both pre-K and Head Start are proposed for increases in funding in next year’s federal budget. The danger is that the opportunity to help poor children is being squandered on poorly conceived programs that do not accomplish what is hoped for them. In fact, both programs are inaccurately described and understood in their reality, but exist instead in some idealized fashion in the minds of policy makers and advocates. No new policy initiative should be launched without an accompanying rigorous evaluation of its effects. Researchers should insist that policies like the Preschool Development Grant are evaluated objectively to determine if they actually address the problems for which they were adopted to solve, and if they do not, are reworked until they do. It is a disservice to children to do otherwise.

[i] http://www2.ed.gov/programs/preschooldevelopmentgrants/index.html.

[ii] http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/campaign-k-12/2016/07/house_panel_oks_cut_to_educati.html?cmp=eml-enl-eu-news2

[iii] Farran, D. & Lipsey, M. (in press). Evidence for the benefits of state pre-kindergarten programs: Myth and misrepresentation. Behavioral Science and Policy.

[iv] Metz, A., Naoom, S.F., Halle, T., & Bartley, L. (2015). An integrated stage-based framework for implementation of early childhood programs and systems (OPRE Research Brief OPRE 201548). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

[v] Reardon, S. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In G. Duncan & R. Murnane, (Eds). Whither opportunity: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

[vi] Puma, M., Bell, S., Cook, R., Heid, C., Broene, P., Jenkins, D., Mashburn, A. & Downer, J. (2012). Third grade follow-up to the Head Start Impact Study final report, OPRE Report # 2012-45, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Lipsey, M. W., Farran, D. C., & Hofer, K. (2015). A randomized control trial of the effects of a statewide voluntary prekindergarten program on children’s skills and behaviors through third grade (Research Report). Nashville, TN Vanderbilt University, Peabody Research Institute. Available from: http://peabody.vanderbilt.edu/research/pri/.

[vii] https://pdg.grads360.org/#program

[viii] http://ceelo.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ceelo_pde_ta_webinar_setting_stage_2015_03_04_web.pdf

[ix] Riley-Ayers, S. & Barnett, S. (June 2015). CEELO short take: State approaches to evaluating preschool programs. Retrieved from http://ceelo.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ceelo_short_take_pdg_eval_guidance.pdf.

[x] Chien, N., Howes, C., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R., Ritchie, S., Bryant, D., Clifford, R., Early, D., & Barbarin, O. (2010). Children’s classroom engagement and school readiness gains in prekindergarten. Child Development, 81, 1534-1549; Weiland, C., Ulvestad, K., Sachs, J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2013). Associations between classroom quality and children’s vocabulary and executive function skills in an urban public prekindergarten program. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28, 199‐209; Gordon, R., Hofer, K., Fujimoto, K., Risk, N., Kaestner, R. & Korenman, S. (2015). Identifying high-quality preschool programs: New evidence on the validity of the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS-R) in relation to school readiness goals, early education and development. Early Education and Development, 26, 1086-1110.

[xi] Farran, D.C. & Hofer, K. (2013). Evaluating the quality of early childhood education programs. In O. Saracho & B. Spodek (Eds.), Handbook of Research on the Education of Young Children (pp 426-437). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

[xii] Farran, D. & Lipsey, M. (October 8, 2015). Expectations of sustained effects from scaled up pre-K: Challenges from the Tennessee study. Evidence Speaks, 1 (4). Washington, DC: Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/papers/2015/10/08-expectations-of-sustained-effects-from-scaled-up-prek-challenges-tennessee-study-farran-lipsey.

[xiii] Farran, D. C., Meador, D. Bilbrey, C. & Vorhaus, E. (2014). Advanced Narrative Record. Unpublished instrument available from D.C. Farran, Peabody Research Institute, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

[xiv] Peisner-Feinberg, E. S., Schaaf, J. M., Hildebrandt, L.M., & Pan, Y. (2015). Children’s pre-K outcomes and classroom quality in Georgia’s Pre-K Program: Findings from the 2013–2014 evaluation study. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute.

[xv] Bassok, D., Lathan, S., & Rorem, A. (2016). Is kindergarten the new first grade? AERA Open, 1, 1-31.

[xvi] Cascio, E.U. & Schanzenbach, D. (2014). Proposal 1: Expanding preschool access for disadvantaged children (p.2). In M. Kearney & B. Harris (Eds.), The Hamilton Project: Policies to address poverty in America. Washington, DC: Brookings.

[xvii] Lipsey, Farran, & Hofer, 2015.

[xviii] http://ffyf.org/3-6-million-going-support-children-flint-mi-head-start-program/

[xix] Educational Services for Children Affected by Lead Expert Panel. Educational interventions for children affected by lead. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015, pp. vii.

[xx] http://www.pasrmn.org/MELF/Scholarship_Pilot_Research

[xxi] Quinton, S. (September 4, 2015). States agree on need for ‘preschool,’ differ on definition. The Pew Charitable Trusts/Research & Analysis/Stateline. http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/

[xxii] Ladd, H., Muschkin, C., & Dodge K. (2014). From birth to school: Early childhood initiatives and third grade outcomes in North Carolina. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33, 162-187.

[xxiii] http://ncchildcare.dhhs.state.nc.us/general/mb_ncprek.asp

[xxiv] http://www.strategiesforchildren.org/news_articles/1503_SHNS_PrekBill.htm

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).