Export decline hits Midwestern communities, signals ongoing shift toward services exports in large metro areas

In July 2017, President Trump announced “Made in America” week to showcase U.S.-produced goods from all 50 states. In fact, advocating for U.S.-produced goods has been one of the most consistent positions of President Trump’s campaign and administration. “Made in America” proclamations are not new: presidents Obama and George W. Bush used similar rhetoric when discussing American manufacturing. The previous and current efforts reflect that support for American-made goods remains a key pillar of U.S. trade policy, since manufacturing accounts for 56 percent of total U.S. exports.

But new Brookings data on goods and services exports in U.S. metro areas suggest cause for concern, as well as the need to diversify American trade policy strategies.

Our new analysis of goods and services exports for 381 metropolitan areas shows that, in 2016, exports did not drive significant economic growth in most parts of the country. The export slowdown was linked to declines in manufacturing exports, particularly in the industrial Midwest.

The recent decline marks a departure from the national post-recession trend. Between 2009 and 2014, exports accounted for 26 percent of the growth in U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). But U.S. exports declined in 2015 and again in 2016, hampered by a strong dollar and sagging global demand. Exports recovered slightly in the first quarter of 2017, but not enough to counteract losses in the previous two years.

Ultimately, national exports arise from the collective export performance of the nation’s diverse regional economies and the firms that cluster in them. In 2016, 381 metropolitan areas generated 87 percent of national exports. Reflecting the national decline, total exports within the nation’s metropolitan areas declined by 1.9 percent from 2014 to 2016. The drop in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas was slightly steeper (2.0 percent), even as these areas’ aggregate GDP grew by 1.9 percent. The combination of export decline and broader economic growth meant that, for the first time since 2009, average export intensity—the share of regional GDP generated by exports—dipped below 10 percent in large metro areas.

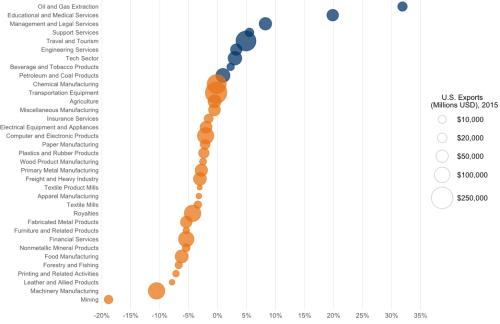

The overall national decline masks considerable variation among industries. Only 8 of 35 major industries experienced export growth between 2014 and 2016: educational and medical services, management and legal services, commodities, travel and tourism, and the technology sector.

Meanwhile, most losses occurred in manufacturing, which experienced a $70 billion decline in exports from 2014 to 2016 after helping drive the post-recession recovery. Over the past two years, machinery manufacturing was hardest hit (-$30 billion), followed by chemical manufacturing (-$10 billion). Finance and insurance exports also declined $15 billion in the same period.

The rise of services exports and the decline of goods exports accelerated a longer-term industrial transition occurring in U.S. metro areas. Within the 100 largest metropolitan areas, services increased from 40 percent of total exports in 2008 to 47 percent in 2016. If current trends continue, services will overtake goods as the largest export category among this group in 2020 (as signaled by the dotted lines in Figure 2).

How did the export slowdown impact different parts of the country? Of the nation’s 381 metro areas, 64 percent registered export declines (including 71 of the 100 largest metros). The decline in manufacturing exports hit the Midwest hardest. That region, which generated 24 percent of total national exports, accounted for 48 percent of the national export decline between 2014 and 2016.

Many of the metro areas experiencing the steepest export declines specialize in aspects of machinery and automotive manufacturing, including large Midwestern metro areas such as Akron, Cleveland, Detroit, Toledo, and Youngstown, as well as smaller cities like Canton, Ohio; Columbus, Ind.; and Peoria, Ill. The slowdown in these manufacturing industries also contributed to significant declines in Oklahoma metro areas like Oklahoma City and Tulsa.

Metro areas in the South and West were more likely to experience export growth. Of the 29 large metro areas that expanded their export base in 2016, 25 were located in these regions. Many of the fastest growers specialized in aircraft production (e.g., Seattle, Tucson, and Wichita) or oil and gas (e.g., Baton Rouge and New Orleans).

Meanwhile, 371 of the nation’s 381 metro areas saw an increase in education and medical services exports, including all 100 large metropolitan areas. The growth of these services exports in urban areas signifies the increasing attractiveness of U.S. universities and hospitals to international visitors willing to pay top dollar for a world-class education or globally unique health services.

The tech sector contributed a smaller share of export growth but remained a bright spot in many large and mid-sized metro areas, ranging from Boston and New York to St. Louis, Little Rock, and Columbus, Ohio.

What does this all mean for the nation’s economic health? Measured by what U.S. metro areas produce for consumption outside their borders, the nation’s tradable base continues to shift toward services. After a significant expansion in the post-recession period, manufacturing exports sagged, dampening overall exports in small and large metro areas across the industrial belt. The latest export data point to additional evidence of a broader slowdown in manufacturing, particularly in the automotive sector—a trend observed by our colleague, Mark Muro. This presents near-term challenges for President Trump’s vision, in which administration policies foresee large numbers of production jobs to return to industrial communities.

Thus, a U.S. trade strategy cannot solely be a manufacturing strategy. The growing weight of services exports—management, legal, technology, education, and medical—also must be recognized and central to a Trump administration “Made in America” agenda. For example, opening up Asian markets to U.S. services exports was a core policy rationale for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and following the decision to withdraw from TPP, effectively shaping a services exports strategy remains a critical imperative. Even with its recent downturn, the manufacturing sector will be an important driver of U.S. exports and a notable source of export-related jobs. Accordingly, trade policy must continue to confront discriminatory practices, offshoring—fueled by unfavorable exchange rates and globalized labor markets—and encourage upgrades to the technology and skills base that sustain competitiveness. However, a balanced approach also must place more emphasis on promoting and expanding access for U.S. services exports by addressing barriers like physical presence requirements, local data storage mandates, foreign equity limits, temporary staff relocation restrictions, or cross-border data flow constraints.

This pragmatic approach to global trade is being pursued locally in a diverse range of cities and metropolitan areas. Take Milwaukee, for example, which has placed water technology at the center of a broader exports and foreign direct investment strategy as part of the Global Cities Initiative (GCI). Milwaukee 7, the region’s economic development organization, and The Water Council, an industry cluster group, are promoting the services and goods produced by 200 local companies involved in developing water technology solutions for the rest of the world, particularly for countries like China. This includes support for small and mid-sized companies through the region’s Export Development Grant Program. Other GCI metro areas are undertaking similar strategies, whether nurturing key traded clusters in unmanned aerial systems in Syracuse, genomics in Philadelphia, or insurance technology in Des Moines.

Local efforts like Milwaukee’s cannot completely immunize regional economies from broader shifts in industries, technologies, and global supply chains. Indeed, like most other major metro areas, Milwaukee experienced a decline in exports in the recent period. But over time, these economic development efforts yield positive results in helping small and mid-sized companies to create globally competitive products and reach international markets. Encouragingly, exporting firms tend to have higher growth, employ more people, and pay better wages. Much has been written, including by us, about the very real disruptive costs of trade and broader global integration. Indeed, cities, regions, states, and the federal government must do more to address these costs. But these metro-level efforts also remind us that national leaders can learn from—and align policy and programs behind—smart local strategies to connect more firms and workers to global market opportunities.

The authors thank Shangchao Liu for research assistance.

The Export Monitor is made possible by the Global Cities Initiative, a joint project of Brookings and JPMorgan Chase to help metropolitan leaders grow their regional economies by strengthening international connections and competitiveness. GCI activities include producing data and research to guide decisions, fostering practice and policy innovations, and facilitating a peer-learning network. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact, and makes all final determinations on its own scholarly activities, including the research agenda and products. To learn more about the Global Cities Initiative, visit the homepage here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).