For more details on the Breadth of Learning Opportunities project and tools, please read the three-page project description.

What should children be able to learn at school? Are math, reading, and science enough for the 21st century? From the earliest learners to adolescents, students across age groups are missing out on critical learning opportunities. These opportunities are those that help us develop a range of skills, essential to tackle the challenges of our dynamic, rapidly growing world and transform us into our “better selves”—mindful, empathetic, critical-thinking, creative, and collaborative beings.

In the last two decades, there has been a global movement toward rethinking the learning opportunities children need to thrive in their lives, careers, and make meaningful contributions to their local and global communities. As a result, national curricula and policies have increasingly reflected learning approaches that focus on the development of the whole person, providing students with opportunities to develop a broad range of skills.

Governments have recognized the importance of areas such as social and emotional learning, culture and the arts, and health and nutrition in 21st century education. In a mapping database of national policies in 102 countries launched by the Center for Universal Education (CUE) at Brookings, nearly 80 percent have included breadth of skills somewhere in their national education mission statements, curriculum, or other policy documents. For example, South Africa’s national curriculum statement indicates that, upon completing formal education, students should be able to identify and solve problems and make decisions using critical and creative thinking as well as work in collaborative environments. It further states that students should learn to communicate effectively through the use of visual, symbolic, and language skills; be able to use science and technology; and demonstrate responsibility toward the environment, the health of others, and an understanding of the world.

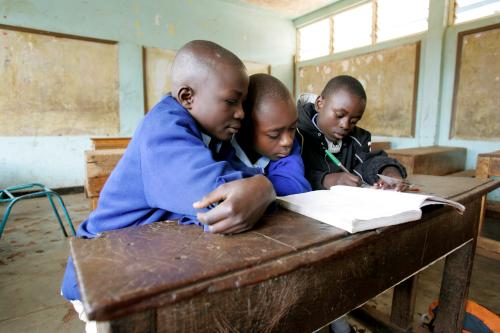

Despite ambitions such as these, many students continue to learn in traditional school environments where they sit at desks, passively listen to a teacher’s lecture, and memorize a limited curriculum that is further reinforced through often outdated assessment practices. Teachers often receive little professional support to deliver a balanced curriculum and may, if curriculum and pedagogies are not updated and resourced, continue to use instructional practices that emphasize memorization and repetition. Students in these settings tend to spend most of their class time bored and disengaged. In other cases, students are burdened with an excessive amount of content. Students in these learning environments are unable to learn at their own pace often leading to delays in the development of critical skills.

All children deserve to have quality learning opportunities to develop to their full potential, an idea that is reinforced by the Sustainable Development Goals, in particular Goal 4 on education. Aligning national goals with classroom practice and ensuring that teachers have the ability to teach breadth of skills—shifting from a narrow focus on literacy and numeracy—is an important step toward preparing students to tackle 21st century challenges.

During the early discussions of the Learning Metrics Task Force (LMTF), the idea emerged that although we cannot measure all of the learning outcomes that are important—defined by LMTF as seven domains of learning from early childhood to lower secondary education—we could aim to measure the learning opportunities in all of these domains. As a starting point, this would include what is covered in national curricula, but would then examine national examinations, learning materials, and school and classroom practices.

As part of the Skills for a Changing World project focused on the breadth of skills needed for a healthy, vibrant society, CUE and Education International are working together with academics, policymakers, teachers, and civil society leaders. Using the LMTF seven domains of learning as a base for analysis, we are investigating what learning opportunities are being offered to students in each of these domains. Together with an international working group, we are developing a set of tools that governments, teachers, and researchers can use to explore how a breadth of learning opportunities is being articulated at the national level and how that vision is delivered at the classroom level. Recently, EI convened teacher workshops in Zambia and Kenya to develop tools for primary and secondary teachers to assess the breadth of learning opportunities and resources available in their schools. Through document analysis, surveys, and observations, these tools will paint a picture of what classrooms look like in the context of the national goals for education.

Now more than ever, children require a new generation of skills to navigate various contexts within our dynamic environment. We have seen over the past decades that access to literacy and numeracy is not enough. Ensuring that the application of education systems provide children with opportunities to develop a broader set of skills for life, learning, and work will allow them to participate effectively and make meaningful contributions to their societies and the world. For this reason, we hope that these tools will help countries reflect on how the LMTF seven domains are addressed in national curricula, teacher training, assessments and examinations, and teaching and learning processes—all factors in the education system that affect children’s learning environments.

If you are interested in receiving updates on this project, please send an e-mail to [email protected].

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Examining breadth of learning opportunities in 21st century education systems

October 31, 2016