Despite many advances in our understanding of how out-of-school factors relate to test scores, there is still much to understand about what is driving differences in student achievement across geographical areas. This question is particularly salient for explaining differences among students in their early elementary years, who have experienced comparably less exposure to formal schooling but arrive at elementary school with systemic gaps in test score performance. One under-explored area for examining early differences in achievement is children’s local health environments, such as the local presence of physicians trained in pediatric care.

Physicians trained in pediatric care play an important role in early childhood. Not only do these providers protect the health and well-being of young children, but they also play a critical role in catching and treating early developmental delays and other conditions that can affect learning, such as impaired hearing and eyesight. Despite their important role in child development and early childhood learning, we do not have much understanding of the role that pediatric physicians play in academic achievement, nor of how accessible they are from one community to another.

We do know that poor access to pediatric care is bad for kids. In areas with low physician supply, families may be more likely to miss well-child visits and other non-emergency care, especially when the drive is long and parents cannot miss work. Researchers have linked the local supply of primary care physicians to numerous health outcomes for children, including overall access to care, prevalence of unnecessary hospitalizations, and local rates of infant mortality and low birth weight. These health outcomes are linked to educational success in both direct and indirect ways. For example, lower birth weight has been directly linked to reduced cognitive performance, and preventable hospitalizations for conditions like asthma have been linked to reduced academic achievement due to increased school absences.

New research on students’ access to pediatricians

To learn more about this potential relationship, I recently published a study in Health Services Research with my co-author, Benjamin Domingue, that maps every practicing pediatric physician in the country to their local school districts. We use data from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile to construct the district-level measure of physician supply, which we then use to explore some basic questions: How are pediatricians and family physicians distributed across school districts? Are they equally accessible to all students, or do some students have better access than others?

Our secondary aim was to describe the relationship between the national distribution of these physicians and local levels of early academic achievement to better understand how these two factors might be related (albeit without necessarily identifying the causal effects of physicians on student test scores). To do this, we use nationally normed third grade test scores from the Stanford Education Data Archive.

Our analysis produced several key findings.

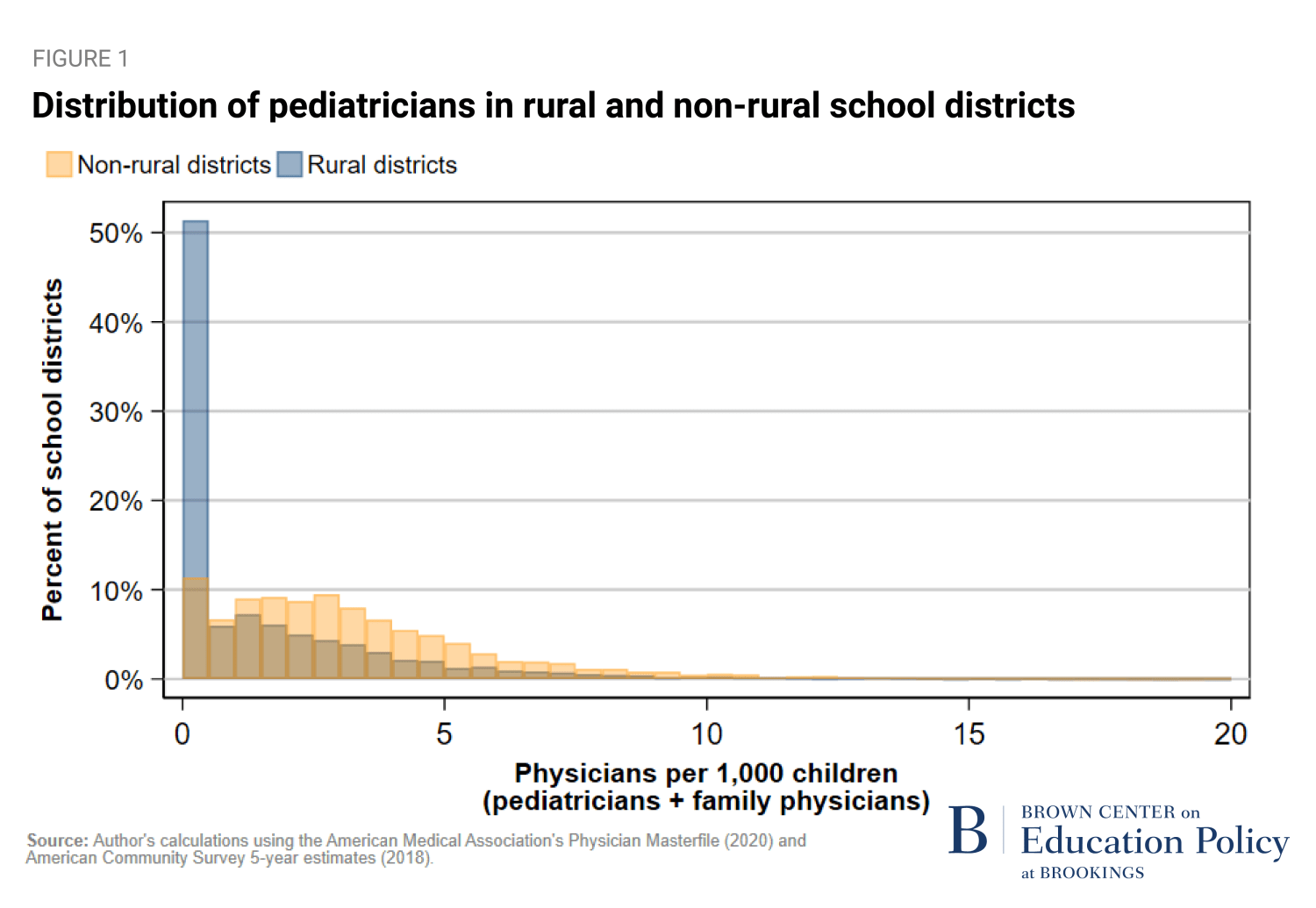

First, pediatric physicians are highly unequally distributed across school districts. Nearly 30% of 12,297 districts have no pediatric physician, which includes 49% of rural districts (Figure 1).

Since only about 15% of visits to family physicians are from children, we did an additional analysis focusing exclusively on pediatricians. The inequality in access to pediatricians is even more extreme: 65% of all school districts have no pediatrician within their boundaries, including 89% of rural school districts.

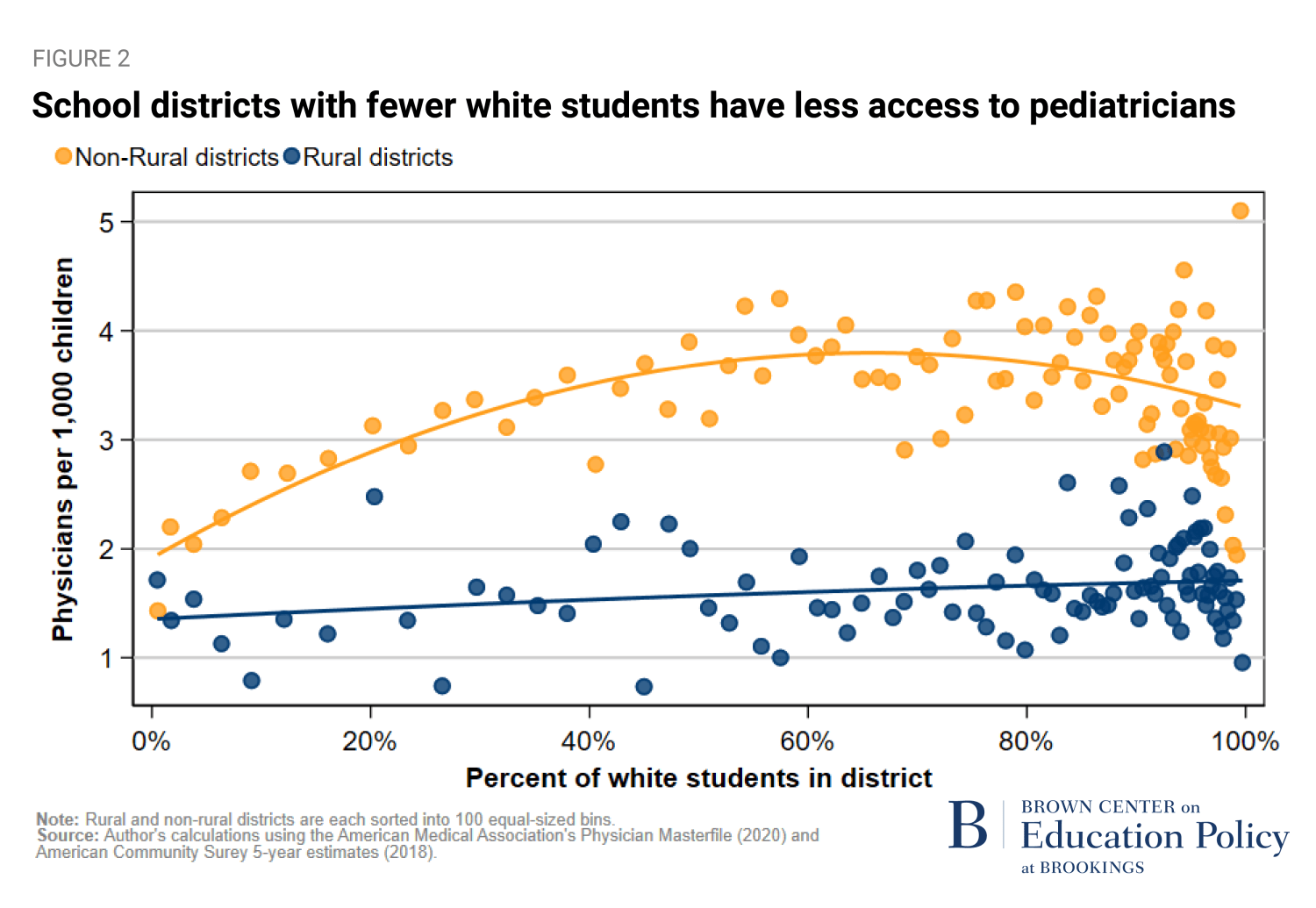

We were also concerned about differences in access to health care by different racial groups even within the same geographic category, and we found that rural children of color in particular have very little access to pediatric care. In Figure 2 below, we plot the white student share along the x-axis and access to pediatric physicians on the y-axis. Rural districts (blue dots) have systematically lower access to pediatric care compared to non-rural districts. In both rural and non-rural settings, districts with the least access are disproportionately in communities with low shares of white students (on the left side of the figure).

Second, districts that have more physicians per child tend to have higher academic test scores in third grade. Determining the causal effects of physicians on student test scores is difficult with the data currently available. However, at minimum, we can get a sense of the correlation between the local supply of pediatric physicians and test scores.

To do this, we organized school districts into thirds: the top third represents districts with the highest supply of pediatric physicians, and the bottom third represents districts with the lowest supply of physicians. Table 1 below shows that the bottom third of districts have, on average, only 0.05 pediatric physicians per 1,000 children. The top third of districts have over 100 times that amount.

Looking at achievement levels, average third grade test scores in high-supply districts are 0.12 standard deviations above average third grade test scores in low-supply districts. (Note that these test scores represent the average gain across math and ELA.) This difference in test scores is especially notable since the average socioeconomic status (SES, an index measure based on average household income and other measures) in high-supply districts is actually a bit lower, on average, than in low-supply districts.

Third, we analyzed the national relationship between physician supply and test scores and found that the association is most pronounced for districts with low supply. In low-supply districts, an additional physician is associated with a 0.16 SD increase in average third grade test scores. Though mapping changes in standard deviations onto months or grades of learning is an imprecise, ballpark exercise, we can think of 0.16 SDs as being roughly equivalent to 90 added days of learning, or an additional half of a grade level of achievement in the average 180-day school year. For comparison, in high-supply districts, an additional physician is associated with a 0.004 SD increase in average test scores.

What does this really tell us?

Our data show that not only are pediatric physicians very unequally distributed across student populations, but also that students with low levels of access to nearby pediatric care tend to be the same students that have lower levels of early academic achievement, even when controlling for socioeconomic status.

To address the disparity in access to pediatric care, we make two main recommendations. First, policymakers should continue expanding opportunities for districts to establish school-based health centers. Expanding access to pediatric care through schools, including school-based vision, hearing, and dental care, can be effective, since the vast majority of U.S. children are legally compelled to attend school. Accessing care at school eliminates many traditional barriers to health care access, including the cost of transportation and the inability of many parents to take time off work. Additionally, families who mistrust, fear, or do not know how to participate in the U.S. health care system may be more likely to participate in early childhood health services through a trusted conduit such as their local school.

Second, since physician training is publicly funded, policymakers and practitioners should improve policies and practices aimed at distributing pediatric physicians in a more equitable way, especially if communities are reaping uneven benefits from taxpayers’ contributions to the U.S. medical workforce. Expanding medical student loan forgiveness may be an effective way to achieve this redistribution, since research has demonstrated that physicians with more education debt are less likely to serve in health professional shortage areas. Medical schools should focus more attention on recruiting students from the communities that need better access to care since students from medically underserved communities are more likely to practice in those communities. Additionally, medical schools must work to expand rural training opportunities, since students in the health care profession who are exposed to underserved populations during education and training are more likely to care for this same population once in practice.

We would like to emphasize that regardless of whether the observed association is causal, it is of grave concern that children throughout the U.S. systemically face barriers to access and success in two sectors—health care and education—that are deeply intertwined with child well-being and outcomes across the life course. It is imperative that researchers, practitioners, and policymakers engage in cross-sector collaboration to remove these barriers and create more equitable access to opportunities for all children.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).