It is well-known that throughout cities in the United States, there is a significant set of economic disparities between white people and people of color. In this blog, we explored the current contours of economic opportunity in the five counties (Prince George’s, Montgomery, Arlington, Alexandria, Fairfax) and Washington, D.C. that make up the D.C. metropolitan area better known as the DMV.

In an effort to identify trends relevant to economic mobility in the DMV, we reviewed extant 2019 data on life expectancy, income, unemployment, poverty, education, and homeownership by race in the DMV. Each of these factors is commonly understood to have an impact on an individual’s ability to experience economic well-being and generate wealth.

An opportunity to support thriving Black life in Washington, D.C.

What we found is that within these five counties and Washington, D.C., Washington D.C. exhibited the largest negative racial disparities in life expectancy, income, unemployment, and poverty. Black residents in D.C., in particular, experience the greatest negative disparities in these categories.

For example, Black life expectancy in Washington, D.C. was the lowest among all races at an average of 72.7 years. This compared unfavorably with an average of 88 years for white people, 88.3 years for Latinos, and 88.9 years for Asians in Washington, D.C.. Black people also had the lowest per capita annual median income and the greatest disparities in income at $29,927 when compared to that of white people at $92,758 and Latinos at $41,151. In addition, in 2019, Black people in Washington, D.C. experienced the highest unemployment rate, 4.8%, of any of the jurisdictions we reviewed. The largest percentage of Black residents living below the poverty line, 21.6%, lived in Washington, D.C..

The areas in Washington D.C. with the greatest disparities are east of the Anacostia River and are legacy redlined communities. It is clear that policymakers have opportunities to do more to support the economic and general well-being of residents who live in these communities.

Some important distinctions

But there were some important differences among the jurisdictions which could inform further policy inquiry. For example, in Montgomery County, Maryland, Black and white 2019 unemployment rates were relatively low and almost identical, suggesting that Montgomery County may be pursuing a number of policies and approaches to ensure equitable employment.

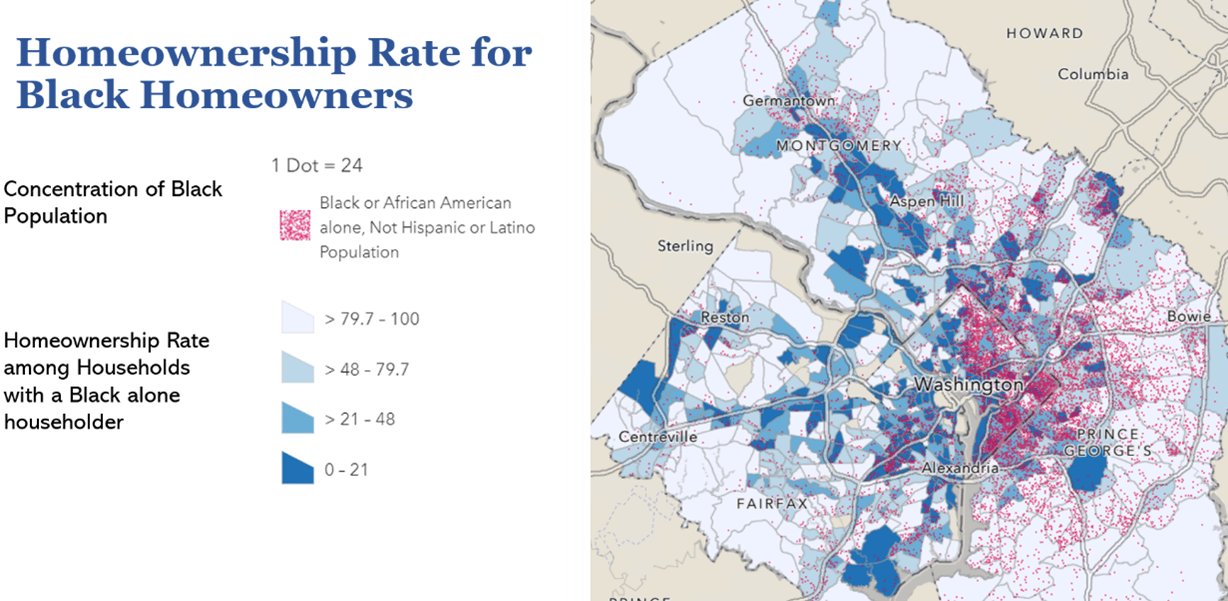

We also found that Prince George’s County has the highest Black homeownership rate among the jurisdictions reviewed. Homeownership depends on a complex set of factors, but it is clear that Prince George’s County offers some important lessons on Black homeownership that could inform other efforts to increase wealth among communities of color across the DMV.

While we found that Latinos experienced the highest negative disparities in education across all the jurisdictions reviewed, Washington, D.C. has the highest high school graduation rate among Latinos. This is promising, so it would be valuable to understand what is driving this trend in the Washington, D.C. We also found that in Arlington County, Asians experienced disproportionately high rates of poverty at 20.5%.

These nuances are important to note and for policymakers to address and provide opportunities for cross-fertilization of policy approaches across the DMV.

Racial wealth gap

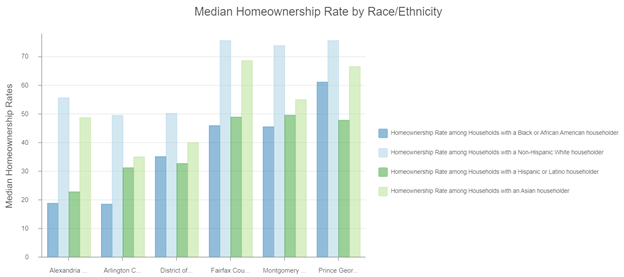

Because wealth in the United States is heavily determined by homeownership and income, we provide some additional geographical analyses. Within the five counties and Washington, D.C. we reviewed, there are large negative racial disparities in income and homeownership. Black and Hispanic/Latino residents experience the greatest negative disparities in the two wealth measures we analyzed.

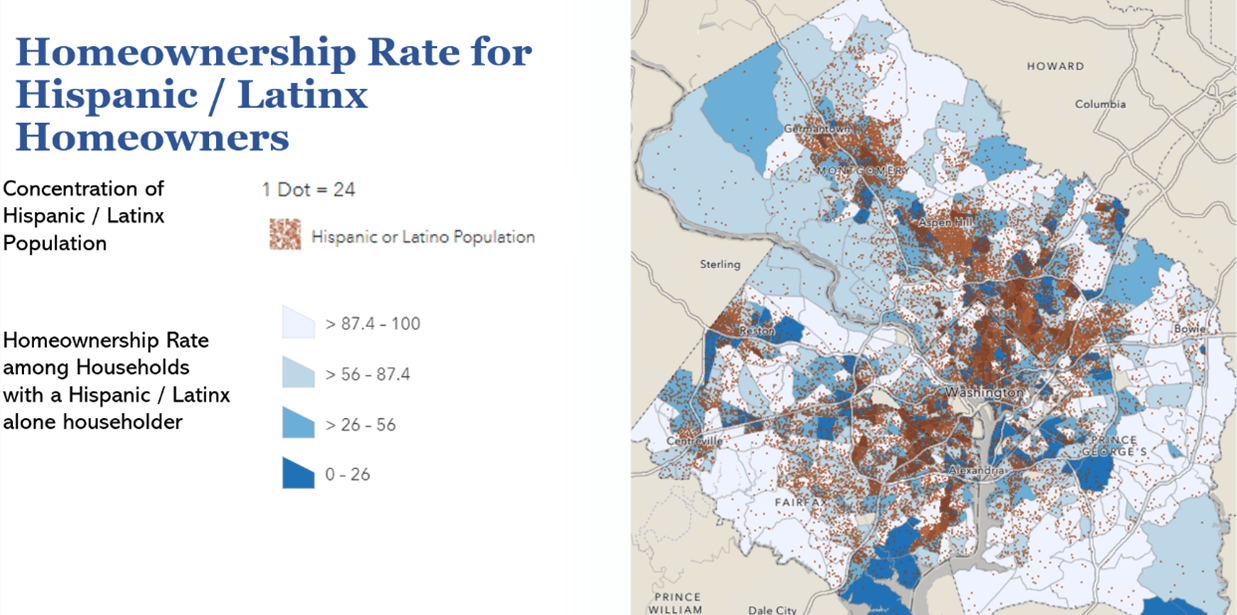

We used income and homeownership data from the American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Census to identify groups of census tracts where people of color had the lowest income in the region. We did an additional overlay to name places in the D.C. region where homeownership rates among Blacks and Latinos remain the lowest. Through a visual analysis of these trends in location, we found “hotspot”[i] areas suffering disproportionately from the persistent racial homeownership gap.

Racial homeownership gap

Overall, across the jurisdictions we analyzed, there is a $156,000 gap in median home value between Black and white residents. Additionally, Black residents are nearly two times as likely to be rent-burdened, meaning that housing costs ate up 30% or more of a household’s income. Both of these factors contribute to the difficulties Black residents experience when trying to accumulate generational wealth through homeownership.

The most concentrated and contiguous disparities occur in the eastern part of the region, in Washington, D.C. east of the Anacostia River and inside the beltway in the western portion of Prince George’s County. The disparities in northern Virginia are relatively more dispersed compared to the rest of the region and include co-occurring and co-located inequities being experienced by Hispanic/Latino and Asian Communities.

Black people consistently have the lowest homeownership rates of any race or ethnicity in the region. However, on average across the region, about 20% of homeowners in each county identify as either Hispanic, Asian and American Indian, with Hispanics making up the largest portion of this group. In Montgomery County, Fairfax County, and Prince George’s County, the census tracts with the highest concentrations of Hispanic/Latinos display homeownership rates under 23%.

Racial Income Gap

Black people consistently have the lowest homeownership rates of any race or ethnicity in the region. However, on average across the region, about 20% of homeowners in each county identify as either Hispanic, Asian and American Indian, with Hispanics making up the largest portion of this group. In Montgomery County, Fairfax County, and Prince George’s County, the census tracts with the highest concentrations of Hispanic/Latinos display homeownership rates under 23%.

Racial Income Gap

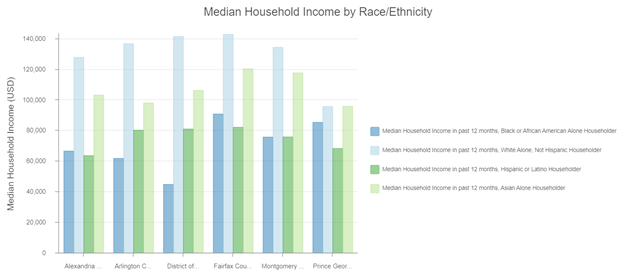

Across the counties included in the study, Black people and Hispanic/Latinos consistently experience the lowest median incomes in the region. In the places where the income disparities are the greatest Black and Hispanic/Latinos have median incomes of $45,072 and $63,862 respectively. In Washington, D.C. specifically, the disparity between white and Black households is the most disproportionate as the median household income for white residents, at $141,650, is over three times higher than that of Black residents, which is $45,072. Disparities between whites and Hispanic/Latinos are the deepest in Alexandria City, where Hispanic/Latinos earn a median household income of $63,862 and white people earn $141,650, and where Latinos also have the lowest median household income in the region. Montgomery County and Washington D.C. also have high levels of income disparity. In both counties, white people have a median household income about 1.75 times greater than the Hispanic/Latino population.

Policy opportunities

Black and Latino residents in the D.C. metro area are not afforded the same opportunities that their white counterparts are when it comes to policies and practices in hiring, homeownership, and education. Local policymakers should focus on promoting opportunities for higher incomes, homeownership rates, educational opportunities and environments, and services that promote better health and well-being outcomes.

Footnote

[i] We define four types of “hotspots” in our research. When there is a grouping of two or more census tracts with high concentrations of either a) Black or b) Latinos living with either c) income below the regional median or with d) low rates of homeownership, these locations light up like beacons problem areas that would most benefit from targeted community support. Our analysis starts with locating high concentrations of Black and Latino populations. This approach hones in on areas where the most impact can be made to improve the lives of a large number of people. We then determined the level of disparity around for income and homeownership. The tracts that show a concentration of both our populations of interest and low income or low homeownership rates are the places on which we recommend additional focus, the “hotspots”. In the following sections, we describe trends in focus areas based on low measures in our two wealth indicators and lessons learned from our research that hopefully encourage community organizations as well as local governments to pay attention to the massive disparities being allowed to fester in their neighborhoods. (Back to top)

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Support for this publication was generously provided by the Greater Washington Community Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Foundation, their officers, or employees.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Economic disparities in the Washington, D.C. metro region provide opportunities for policy action

April 27, 2022