This paper is part of the Spring 2020 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. Research findings are presented in a clear and accessible style to maximize their impact on economic understanding and policymaking. The editors are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Northwestern University Professor of Economics Janice Eberly and Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Harvard University Professor of Economics James Stock. Read summaries of all five papers from the journal here.

The U.S. tax code systematically favors investments in robots and software over investments in people, suggests, a paper to be discussed at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity conference March 19. The result is too much automation that destroys jobs while only marginally improving efficiency.

The paper—Does the U.S. Tax Code Favor Automation by Daron Acemoglu and Andrea Manera of MIT and Pascual Restrepo of Boston University—systematically documents the lopsided tax treatment of capital and labor. The authors then focus on potential fixes, particularly on reducing bonus depreciation, which allows businesses to immediately write off a large portion of their investments in automation rather than over its useful life.

We find that the U.S. tax system favors excessive automation. In particular, the heavy taxation of labor and low taxes on capital encourage firms to automate more tasks and use less labor than is socially optimal.

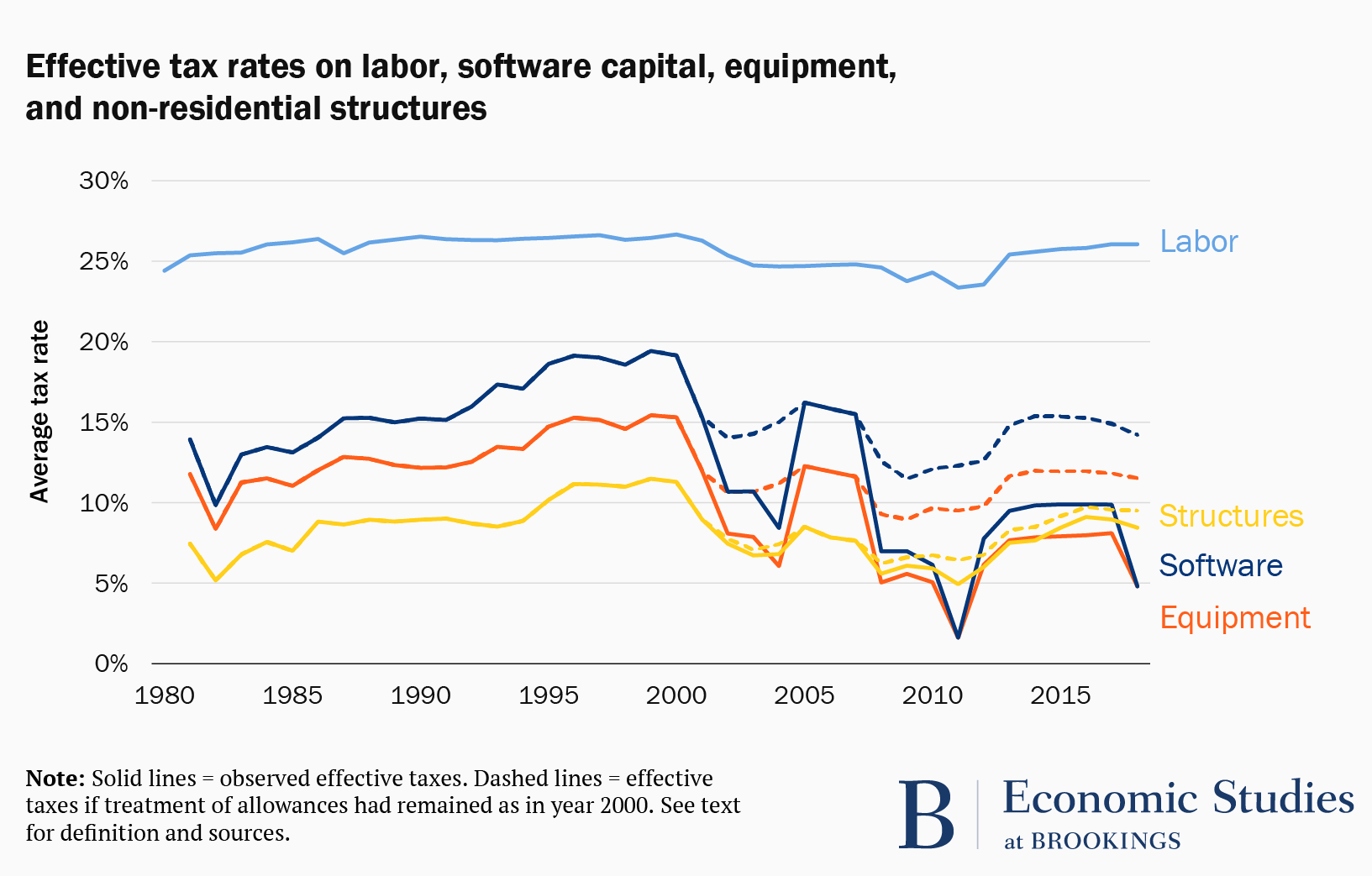

Compared with effective labor taxes that stand above 28.5 percent, the effective tax rate on capital invested in equipment and software has declined to about 5 percent today, largely as a result of favorable depreciation provisions in a series of tax laws enacted from 2002 through 2017 under the George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump administrations, the paper said. Ideally, the author’s analysis suggests, labor should be taxed at 9 percent and capital at 22 percent.

“Most importantly … we find that the U.S. tax system favors excessive automation. In particular, the heavy taxation of labor and low taxes on capital encourage firms to automate more tasks and use less labor than is socially optimal,” the authors write.

They link a variety of negative economic trends to excessive automation, including a decline in labor’s share of income from non-farm businesses (63.6 percent in 1980 and 56.6 percent in 2017), only modestly higher inflation-adjusted wages for the median worker (up 16 percent over the 37-year period), and lower wages for less-skilled workers (down 6 percent for men with a high school diploma, for instance).

Eliminating the capital bias in the tax code, the authors estimate, would raise the number of employed people by 6.5 percent and increase labor’s income share by 1.1 percentage points. More-modest reforms could still increase employment by 1.9 to 2.9 percentage points.

The authors point out that not all increased automation hurts workers. In particular, investing in efficiency-enhancing technology in automated industries where workers have already been displaced would benefit the remaining workers.

They also point out that higher corporate income taxes and lower depreciation allowances could be more effective in addressing excessive automation than increasing taxes on wealthy individuals.

“The beauty of getting rid of distortions in the tax system is that you are leaving automation decisions in the private sector but you are getting rid of artificial incentives, created by bonus depreciation, to adopt less-than-worthwhile automation,” Professor Acemoglu said an interview with Brookings.

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper. Becca Portman assisted with data visualization.

Citation

Acemoglu, Daron, Andrea Manera, and Pascual Restrepo. 2020. “Does the U.S. Tax Code Favor Automation?” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 231-300.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Kamer Daron Acemoglu is the Elizabeth and James Killian Professor of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and a member of the Temporary Nomination Committee for the National Academy of Sciences; Andrea Manera is a graduate student in economics at MIT; Pascual Restrepo is an assistant professor of economics at Boston University and recently served as guest editor for the Journal of Labor Economics. Beyond these affiliations, the authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this paper or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. They are currently not officers, directors, or board members of any organization with an interest in this paper. No outside party had the right to review this paper before circulation. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of MIT, Boston University, or the National Academy of Sciences.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).