The urgency of improving American students’ skills in math and science is hardly in dispute. Performance in these subjects is increasingly critical to individual and national economic success, yet far too few of our students graduate from high school equipped for post-secondary work in technical fields. For example, the ACT reports that just 46 percent of high school graduates taking its college entrance exams in 2012 met college-readiness benchmarks in math; fewer than one in three did so in science. Among all 17-year-olds, the most recent data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress shows that as many as 36 percent lack even a basic level of math proficiency.

Improving the caliber of our math and science teachers is essential to changing this picture. A large body of evidence confirms that teacher effectiveness is a key determinant of students’ academic progress. Indeed, it is likely the case that, as President Obama has said, “The quality of math and science teachers is the most important single factor influencing whether students will succeed or fail in science, technology, engineering and math.”

Unfortunately, the same labor-market trends that have made math and science skills increasingly valuable to students may make it increasingly difficult to attract teachers with the talent and training necessary to address the challenge. Despite a recent wave of reform, the vast majority of school districts nationwide continue to pay teachers based on salary schedules that fail to differentiate among teachers based on their subject-area expertise. To the extent that teachers with technical skills have better earnings opportunities in other industries, this approach can be expected to produce fewer – perhaps even a shortage – of qualified candidates for math and science teaching jobs.

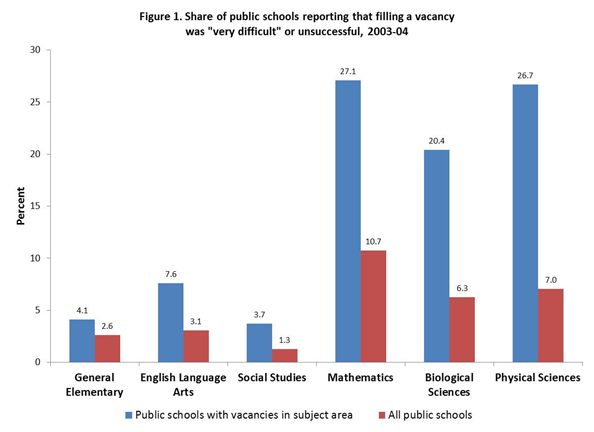

Data consistently show schools struggling to recruit and retain effective candidates for teaching positions in these subjects. In 2003-04, for example, 27 percent of schools with a math teaching vacancy reported that filling that vacancy was “very difficult” or ultimately unsuccessful, as compared with just four percent of schools with vacancies in elementary classrooms (see Figure 1). Even taking into account the fact that general elementary vacancies are more common, schools were more than four times as likely to have a difficult or unsuccessful search in math. The data on vacancies in the biological and physical sciences show much the same pattern.

Source: Author’s calculations based on U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey, 2003–04, Public School, BIA School, and Private School Data Files.

Do these patterns reflect the nature of the job opportunities available to individuals with math and science skills in the broader economy? To shed new light on this question, my Brookings colleague Matthew Chingos and I used a unique administrative database to follow the careers of almost 32,000 high school teachers employed by Florida public schools between the 2001-02 and 2006-07 school years, roughly 3,500 of whom left teaching for a new job in the state during that time. Quarterly earnings data from the state’s unemployment insurance system enabled us to compare the earnings of teachers in different subject areas both while they were teaching and in their new careers.[1]

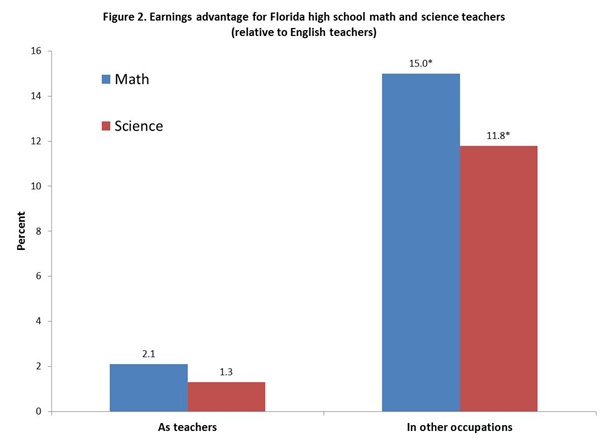

Figure 2 compares the earnings of math and science teachers to those of English teachers for the same group of teachers before and after they left the classroom.[2] Among those who left teaching for jobs other industries, math and science teachers earned 15 percent and 12 percent more, respectively, than did former English teachers after leaving. While they were teaching, these same math and science teachers earned no more than English teachers.[3]

Notes: * significant at p<0.01. N=3,456. The chart presents coefficient estimates from regressions of log annual earnings on district fixed effects (to capture variation in local labor market conditions) and the following subject area indicators: math, science, social studies, foreign languages, and multiple subjects, with teachers of English classes the omitted category. Stayers are those who remained as classroom teachers in Florida public schools from 2001–02 through 2006–07; leavers are those who left for non-teaching jobs within Florida. We exclude teachers who left classroom teaching for other positions in Florida public school districts, teachers who exited the Florida workforce altogether, and likely retirees (those 55 and older). We ignore earnings experienced during an individual’s first year outside of the classroom to allow for transitions between teaching and non-teaching jobs. All observations are weighted by the probability the individual was working full-time, as estimated based on the nationally representative 2004-05 Teacher Follow-up Survey.

This pattern strongly suggests that any efforts by Florida districts to provide better pay for teachers in the high-demand subjects of math and science are insufficient to offset the differences in outside earnings opportunities across subject areas. Although our evidence is limited to one state, data from other sources suggests that the same is true elsewhere. For example, the Institute for Education Sciences reports that more than one-quarter of math and science teachers who left the profession in 2004-05 said that the opportunity to earn better salary and benefits was a “very important” or “extremely important” consideration, as compared with just 13 percent of teachers in other subject areas.

There is a strong case, then, for modifying teacher compensation systems to offer larger salaries for math and science teachers as a means to improve teacher quality—and student achievement—in these subjects. This is not to say that compensation is the only factor influencing decisions to enter and remain in the profession. Research conducted by the University of Pennsylvania’s Richard Ingersoll, among others, shows that general working conditions, the degree to which teachers have classroom autonomy, and other non-monetary factors are at least as important a consideration as salaries in explaining teacher attrition. Yet ample evidence confirms that salary levels strongly influence on teachers’ career paths.

Unfortunately, while offering higher salaries to teachers in high-demand subject areas might initially appear to be less controversial than other forms of differentiated compensation such as merit pay, public opinion data suggests otherwise. In the 2007 Education Next-Program on Education Policy and Governance survey, my colleagues and I found that just 33 percent of Americans would prefer to offer a larger salary increase to teachers “in subject areas where there are shortages, such as math and science” rather than a smaller salary increase to all teachers. In contrast, a majority supported offering a larger salary increase to “teachers who work in challenging schools.” A recent survey of teachers in Washington state conducted by the University of Washington-Bothell economist Dan Goldhaber similarly found that 59 percent of teachers opposed differentiating teacher compensation by subject area.

My conversations with current and former educators suggest that their reluctance to embrace higher salaries for math and science teachers stems in large part from a concern that this approach would imply that other subject areas are somehow less important – and that the contributions made by teachers in those subjects therefore have less value. This concern is understandable. Yet the outside labor market is a reality that school districts cannot simply ignore. By not allowing teacher compensation to vary with outside earnings opportunities, we implicitly ask individuals with strong math and science skills to make a larger financial sacrifice to enter and remain in the profession. It is students who lose out when too few of them prove willing to do so.

President Obama’s recent 2014 budget proposal includes $80 Million in competitive grants to support programs that recruit and train talented math and science educators for high-need schools and $35 Million to pilot a STEM Master Teacher Corps through which effective teachers in technical fields would be rewarded for taking on new leadership roles. These proposals’ prospects in Congress of course remain uncertain. Even if they are enacted, however, they will face an uphill battle absent broader reforms to teacher compensation systems—reforms that may be encouraged from Washington but will ultimately require action by state legislatures and local school boards. Advocates in these venues seeking to make teacher compensation systems more rational—paying more to teachers with stronger outside earnings potential—will need to develop new strategies to overcome the opposition to the idea from both the public and the profession itself.

[1] Details on the construction of this dataset and our analytic sample are available in Chingos and West (2012), which shows that elementary and middle school teachers who are more effective in raising student achievement earn more in other occupations than do their peers.

[2] To assign teachers to subjects, we first computed the percentage of each teacher’s time spent on instruction in each subject in each year (as a percentage of their total time in academic courses that year) and averaged these percentages over all available years. Teachers spending at least 60 percent of their time in a given subject were assigned to that subject; those who did not were assigned to a “multiple subjects” category. Given the prevalence of “out-of-field” teaching, this method likely introduces error in our measurement of teachers’ true qualifications that would bias the analysis towards a finding of no differences in earnings across subject areas.

[3] We also find that science (but not math) teachers are heavily over-represented among teachers who left for a job elsewhere. Assuming that teachers with the best outside opportunities are more likely to leave for other industries, our results will understate the extent to which science teachers as a whole have better earnings opportunities than other teachers outside of teaching.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).