I’ve been teaching 18- to 22-year-old undergraduates at Temple University for about 6 years, so I was really interested in The Varkey Foundation’s new report entitled, “Generation Z: Global Citizenship Survey.” I was curious if my experience with millennials reflected broader global trends.

First some background: I’m a liberal arts instructor, with a Ph.D. in psychology/philosophy, and one of 40 or so instructors who teach a required intellectual history course that aims to expose young people to great books and key ideas while cultivating critical thinking and discursive analytic skills. My profession is often the butt of jokes, and every student hates that my class is a requirement. “What are you going to do with a degree in the humanities?” is a common question, on the basis that my field does not provide hard-skills or specific training applicable to the workplace.

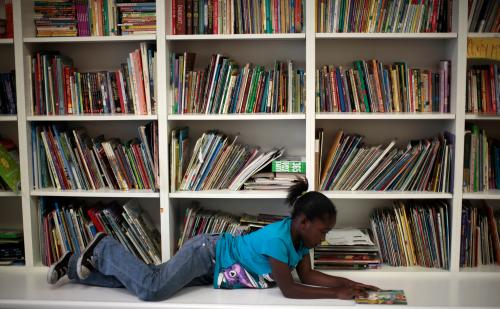

Instead, I offer something more abstract: the ability to leverage so-called “soft-skills” in a way that leads to increased agency. Students learn complex metacognitive skills—the ability to reflect on their value systems and to understand and locate their own ideas within the context of a broad historic, intellectual, and global perspectives. I help them find images they can relate to, pictures of themselves in art, and literature that initially feels unapproachable, distant, or foreign. Through that practice, they become equipped to make meaning out of their experience within a specific and familiar context—a 21st century world that is economically globalized and infrastructurally networked.

These days, I attempt to remind students that even though Brexit and the U.S. Presidential election have put nationalist and isolationist tendencies in the spotlight, humanity has actually become more connected. Interdependence is more important than ever. Trade, transportation, and technology have created a world in which putting any one country first necessitates simultaneously considering the interests of many others.

Students get this intuitively. Millennials understand hyper-linked life in a way that most adults cannot comprehend. They are not wedded to the nostalgic mythos of pre-industrial, self-sustained, small-town economies and homogenous tribal villages. Today’s young people live in a world in which meaning is made on the internet. And the web makes for a strange agora. Somehow, the web-based social life is insulated within a private bezel of handheld devices but also, simultaneously, excruciatingly public and global. How does that affect the way one thinks? The Varkey Foundation-commissioned survey of 15- to 21-year-olds around the world offers some answers. As it turns out, I am not living in a bubble of intellectual urban elitism. The world’s young people are just like the students I encounter every day: tolerant and open-minded.

In the 20 countries represented, the majority of young people thought that their governments “should be making it easier for immigrants to live and work legally.” And about two-thirds say they “have close friends who belong to religions different to their own.” But only 42 percent consider religious faith to be an important part of their lives. In fact, when asked what factor would make the greatest difference in uniting people, “a greater role for religion in society” scored only 5 percent. Less prejudice (30 percent), more socioeconomic equality (21 percent), better access to good quality teaching and education (19 percent) all ranked much higher (curiously, I suspect Pope Francis would say that these are precisely the values that the Catholic Church promotes). Which makes me wonder what “better access to good quality teaching and education” really means. After all, the distinction between many of the values traditionally taught by religious institutions and the social skills taught in the classroom is not so clear.

What’s more confusing is the section of the survey that asks who young people identify as their greatest source of influence when it comes to values—89 percent parents, 78 percent friends, 70 percent teachers, 54 percent books/fictional characters, 53 percent faith, 32 percent sports people, 30 percent celebrities, and 17 percent politicians. These influential people do not seem to be providing them with much comfort. In 16 out of 20 countries, more young people believe “the world is becoming a worse place to live” than believe “it is getting better.”

What is making it worse? What are their fears? Not refugees. More than 80 percent list “extremism and terrorism” and “conflict and war” as their biggest fears. China was an exception; 82 percent were most concerned about climate change. Fortunately, many young people are interested in being part of the solution to these problems. Two-thirds said they crave the opportunity to make a “contribution to society beyond themselves and their family.”

Vikas Pota, chief executive of the Varkey Foundation, sums up the results nicely, “It is reassuring to know that, in the minds of young people, global citizenship is not dead: It could just be getting started.” I would like to think it is a result of their digital nativity. Facebook, Twitter, and Minecraft has an effect on young minds. It is not just about tools. It is about ideas. It is about the structure of consciousness. It is about how one defines the self and how agency and autonomy are leveraged in the contexts of ideas, skills, and knowledge.

I’m not sure I get it, but my kids do. And I like to think that all those massive multiplayer video games, YouTube channels, and always-on cable television shows are honing their perception of the world as a wide network in which geographically divided individuals will always discover ways of working, living, and playing together.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Digital natives are born global citizens

March 16, 2017