The following is a summary of the 14th session of the Congressional Study Group on Foreign Relations and National Security, a program for congressional staff focused on critically engaging the legal and policy factors that define the role that Congress plays in various aspects of U.S. foreign relations and national security policy.

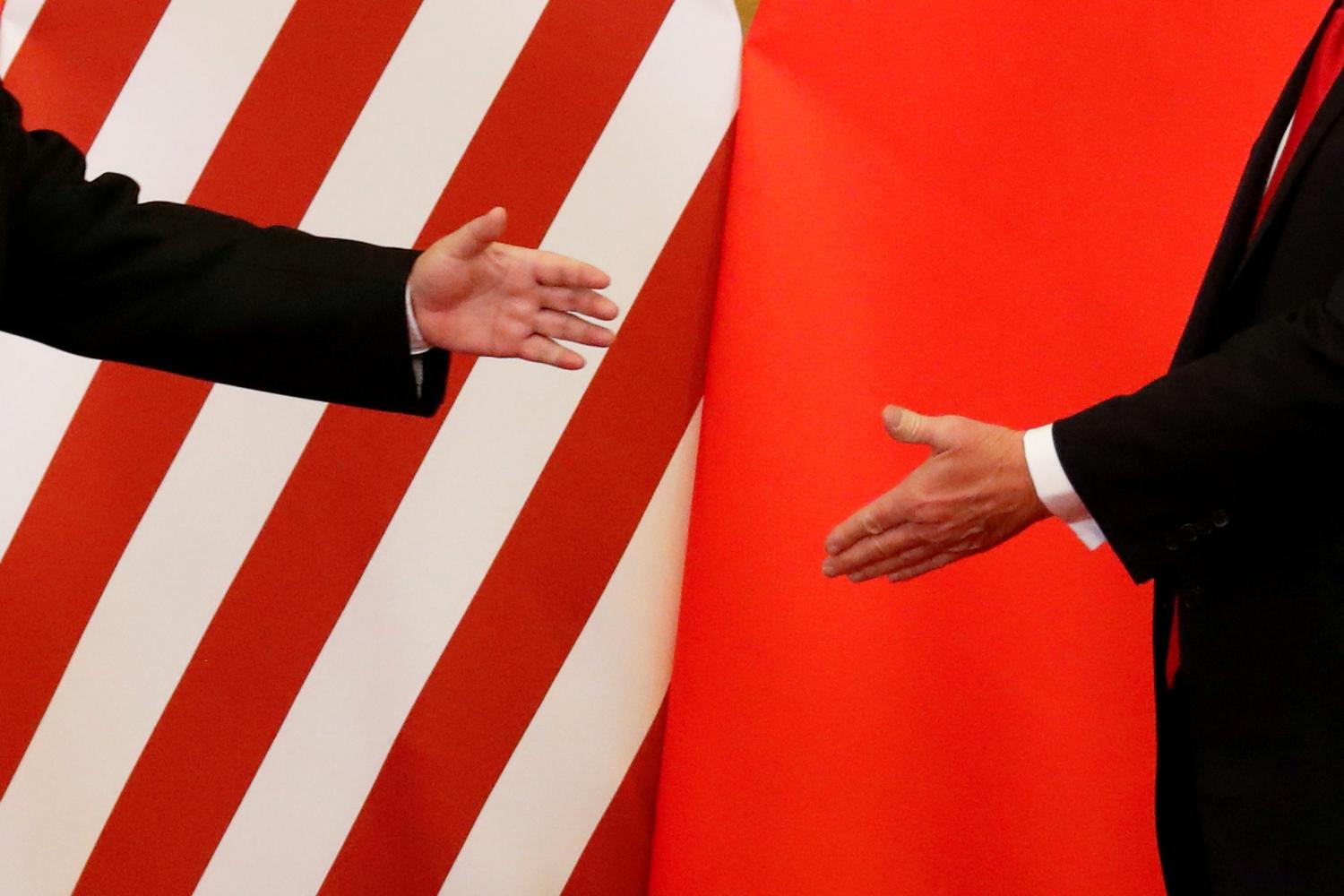

On July 1, 2021, the Congressional Study Group on Foreign Relations and National Security convened over Zoom to discuss separation of powers issues surrounding treaty withdrawal and re-entry. The Trump administration’s withdrawals from the INF Treaty, the Open Skies Treaty, and the WHO Constitution, among other international agreements, and threats to withdraw from NAFTA and NATO focused attention on unilateral Presidential treaty withdrawal. President Trump’s actions raised questions about whether the president can withdraw from a treaty without congressional authorization or when Congress specifically bars withdrawal via statute. The Biden administration’s vocal opposition to such withdrawals has also raised questions about the president’s power to re-enter treaties on a similar unilateral basis.

To discuss these issues, the study group was joined by two experts on the constitutional law issues surrounding international agreements: Ashika Singh, an attorney at Debevoise & Plimpton and a former attorney-adviser at the U.S. Department of State; and Jean Galbraith, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School. The study group coordinator, Scott R. Anderson, also contributed to the substantive conversation, based on his own research on these issues.

Prior to the session, the study group organizers circulated some recommended background reading, including:

- Scott R. Anderson and Christopher C. Fonzone, “Congress Must Protect America’s Treaties,” Foreign Affairs (July 17, 2020);

- Ashika Singh and Catherine Amirfar, “Good Governance Paper No. 12: Treaty Withdrawals,” Just Security (Oct. 28, 2020); and

- Jean Galbraith, “The President’s Authority to Rejoin the Open Skies Treaty,” Lawfare (Feb. 8, 2021).

Anderson also circulated a video of a moot court he moderated at the American Society of International Law’s 2019 annual meeting, which featured several former senior U.S. officials debating Congress’ and the president’s respective authorities over treaty withdrawal.

Ashika Singh opened the discussion by defining a treaty under international law versus a treaty under U.S. law, as well distinguishing among Article II treaties, congressional-executive agreements and sole executive agreements. Under international law, treaties are agreed to in writing by independent states, and must be intended to legally bind the members. By contrast under U.S. domestic law, treaties are limited to those international agreements made by the president and ratified by two-thirds of the Senate. Singh stressed that the vast majority of treaties of which the U.S. is a part are actually not treaties under U.S. domestic law. Rather they are congressional-executive agreements, in which a majority of both houses of Congress pass a law, which the president signs. A third category of agreements, sole executive agreements, is when the president enters an agreement unilaterally. Non-Article II treaties must rely on some other legal or constitutional basis, such as Congress’ power to regulate foreign commerce or the president’s power to recognize foreign countries.

Singh analyzed withdrawal in the context of three different agreements. President Trump’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the JCPOA or Iran Nuclear Deal), a sole executive agreement, raised no constitutional issues. Unilaterally entered into, the JCPOA could be unilaterally withdrawn from. The WHO Constitution, a congressional-executive agreement, permitted U.S. withdrawal, provided the U.S. gave one year’s notice and met its fiscal commitments. Although President Biden reversed President Trump’s proposed withdrawal before the one-year notice period ended, Singh raised the interesting question of what would have happened had President Trump completed withdrawal, but not met U.S. fiscal commitments.

President Trump’s withdrawal from the Article II Open Skies Treaty, which permitted the U.S. and Russia to conduct aerial overflights over each other’s territory to defuse tensions, raised more issues The Open Skies Treaty permitted withdrawal with at least six months’ notice to other treaty members, but Congress, in the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act, required the president to submit notice to Congress 120 days before the official international notice. The Trump Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel rejected this provision as unconstitutionally interfering with the president’s Article II powers to speak as the voice of the nation in foreign affairs and execute treaties. The Supreme Court has never definitively answered the question of unilateral withdrawal in such a scenario, declining to resolve the issue on justiciability grounds in Goldwater v. Carter. Singh discussed the separation of powers issues on both sides and raised the question of whether such a withdrawal was more comparable to legislation (requiring Congress’ acquiescence) or execution of law? She proposed that the question of unilateral withdrawal should be answered on a case-by-case basis, depending on the Constitutional equities at issue. Regarding recognition treaties, the president should have a high degree of leeway to unilaterally withdraw but should have much less leeway in foreign trade agreements, given Congress’ constitutional powers over trade.

Galbraith focused her remarks on the implications of Presidential power to rejoin treaties from which a predecessor had withdrawn. In general, re-entry into multilateral agreements is much more common and practical than for bilateral treaties. With no substantial legal debates or controversies surrounding the President’s power to unilaterally re-join sole executive agreements, Galbraith discussed issues surrounding the re-entry into congressional executive agreements and Article II treaties. No president has ever re-entered an Article II treaty, but presidents have re-entered congressional-executive agreements, such as the International Labor Organization (ILO). The U.S. entered the ILO via congressional-executive agreement in 1934, withdrew in 1977, and then re-entered via unilateral presidential action, in 1980. Galbraith argued that these scant precedents generally supported the proposition that the congressional authorization for entrance into the international agreement remained valid, permitting unilateral presidential re-entry.

Galbraith then discussed how, even if unilateral presidential withdrawal poses separation of powers issues, a broad presidential power to rejoin congressional-executive agreements and Article II treaties could mitigate these challenges. By assuming that congressional authorization for a congressional-executive agreement or Article II treaty continues to exist following a presidential withdrawal, Congress could make unilateral re-entry easier.

The study group then moved to open discussion that touched on a number of issues, including the justiciability of treaty withdrawal and re-entry, whether Congress has acquiesced to greater assertions of presidential power in this area, and the political considerations that underlie related separation of powers disputes.

Visit the Congressional Study Group on Foreign Relations and National Security landing page to access notes and information on other sessions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).