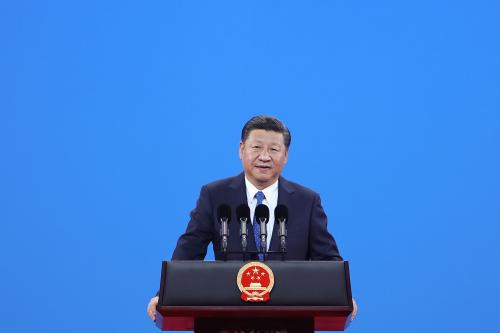

Without question, China’s global footprint has experienced significant growth under President Xi Jinping’s leadership. Aided by the swift and unforgiving consolidation of power across party, state, and military bureaucracies, Xi’s China is unapologetically international in outlook. Under the banner of Xi’s hallmark foreign policy initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Chinese economic and diplomatic ambitions continue to broaden, stretching as far as Latin America, the Arctic, and even outer space. However, a review of China’s engagement reveals that the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) increasingly global outlook did not originate with Xi; rather, he has opted to strengthen the party’s ideological commitment to international leadership and devote greater resources to actualizing China’s geopolitical aspirations. While Xi’s firm grip on power enables the implementation of such a bold foreign policy, his rejection of the collective leadership model leaves Xi singularly responsible for an assertive, international China’s success—or its failure.

Integrally linked to achieving the “China Dream,” the PRC’s expanding diplomatic toolkit enables Beijing to drive global change in a way that supports its own “core interests,” often at the expense of international rules and norms. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) pursuit of a “community of shared future for mankind” (人类命运共同体) is emblematic of the increasingly transnational nature of the party’s ideological aims. Most recently, Belt and Road has been touted by Chinese state media as a key component of “transformations in the global governance system.” When Xi initially became general secretary of the CCP in 2012, onlookers were optimistic that he would turn to economic reform, moving to further liberalize the Chinese economy. Instead, Xi has strengthened the role of the party within the state apparatus, recommitted to state-directed investment, and repeatedly stressed the need for Chinese self-reliance.

MILITARY MODERNIZATION’S RELATIONSHIP TO CHINA’S EXPANSIONIST VIEW

Where Xi’s consolidation of power has enabled him to push through significant practical reform is the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which has seen key shifts in its organizational structure and operational focus. In 2016, the Central Military Commission (CMC) announced the most significant set of reforms to China’s military in the modern era. The directive organizes the forces into joint theater commands, with the goal of integrating various PLA services into a single operational structure for the first time. In theory, the geographic reorganization of the PLA will enable the force to better integrate across services to execute discrete missions, thereby facilitating enhanced power projection capabilities within the Indo-Pacific region. In part through the execution of the 2016 military reforms, the CCP’s endeavors to build a more capable warfighting force that is capable of executing the PLA’s emerging strategy of the “informationalization” of war, which emphasizes gaining operational dominance of the information domain. Furthermore, Xi’s new role as “helmsman” of the PRC is facilitating a renewal in the PLA’s devotion to the CCP and political work writ large. CMC reforms strengthened the effectiveness of the Party’s political control of the PLA, ensuring that the military remains first and foremost loyal to the CCP rather than the Chinese state. The associated anti-corruption campaign has come with the added benefit of silencing alleged critics of Xi. President Xi is keen to couple this growth in the PLA’s military capability with a reassertion of the CCP’s enduring control of the force.

AN EVOLVING APPROACH TO REGIONAL SECURITY ORGANIZATIONS

Today’s China is exploring new ways in which its security apparatus, including the People’s Liberation Army, can be used as an instrument of comprehensive national power in non-combat situations. Nowhere is this more evident than China’s shifting attitude towards regional security organizations and bilateral military-to-military ties. Despite these critical changes in China’s warfighting capabilities, organizational strategy, and military doctrine, a comprehensive analysis of the linkages between China’s increasingly global economic and diplomatic outlook and the ongoing reforms to the PLA has been largely absent from the public debate. However, beneath the surface, China’s approach to regional security has matured in ways that resemble Belt and Road’s expansionist approach to Chinese power projection.

China’s approach to regional security organizations places a sharp focus on a nominal consensus-based decisionmaking process in international organizations. In January 2017, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a white paper outlining “China’s Policies on Asia-Pacific Security Cooperation.“ Proclaiming that, “China stands ready to work with all countries in the region to…steadily advance security dialogues and cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region, and the building of a new model of international relations so as to create a brighter future for this region,” the white paper advances an alternative approach to regional security coordination. This “new model” frames dialogue and discussion as an alternative to an alliance-based structure, as well as argues states do not require a shared values system in order to partner on initiatives. Instead, states should emphasize cooperative elements of the security relationship while “reserving differences.”

Unpacking the PRC’s “new model of international relations” requires parsing CCP rhetoric—designed to persuade onlookers that China’s rise is fundamentally peaceful—from true policy evolution. For example, Chinese claims of non-interference and mutual respect have been called into question given Beijing’s reliance on tools of economic coercion to impart its own conceptions of sovereignty on other states. In the security space, China’s neighbors remain broadly skeptical of enhanced PLA influence, which has continued to grow as the PLA becomes a more regionally capable force. To offset these concerns, China has sought to diversify existing economic and diplomatic mechanisms to include more non-traditional security elements, such as cooperation on counterterrorism and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, rather than creating entirely new mechanisms for security cooperation.

China’s arms transfers have also increased dramatically over the course of the 21st century. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 1999, China was the world’s 11th-largest arms exporter, with an estimated $312 million in arms sales. By 2016, China leaped to be the world’s 5th-largest arms supplier, exporting an estimated $1.1 billion. This increase in weapons sales tracks closely with China’s expansionist economic agenda. The top five destinations for Chinese arms exports in 2016—Pakistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Turkmenistan, and Myanmar—have all officially endorsed China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Continental

Prior to the Xi era, China’s participation in regional security organizations, namely the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), was driven by domestic imperatives. Originally founded as a forum to facilitate the resolution of China’s border disputes with former Soviet satellite states, the SCO’s focus eventually broadened to enlist the support of Central Asian states in controlling China’s restive Xinjiang province. Over time, the organization expanded from a relatively narrow security-oriented focus to incorporate aspects such as people-to-people exchanges and limited economic initiatives.

China’s attempts to deepen the efficacy of non-U.S. led consultative security mechanisms in the Eurasian continent have not been uniformly successful. While China has experienced limited success with the SCO, Chinese leadership in the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA) has failed to take off. CICA is billed a forum for dialogue and consultation on regional security issues in Asia and includes member states from across the Eurasian continent. So far, the PRC has been unsuccessful in its attempts to annualize the mechanism, and all progress has been relegated to Track 1.5 and Track 2 exchange bodies. Despite this, on the margins of the 5th CICA Summit in 2016, President Xi called for the body to “explore the building of a new architecture of regional security cooperation that reflects Asian needs step by step,” a concept reminiscent of the CCP’s broader objective to establish a “community of shared future for mankind.”

As the PLA’s warfighting capabilities have continued to expand, operationalization of military-to-military contacts between China and its neighbors has become more routine and wider ranging in scope. Beginning in 2005, China and Russia began jointly convening the “Peace Mission” series of exercises, which have subsequently grown to incorporate all members of the SCO. Peace Mission 2018 incorporated more than 3,000 troops, and included over 500 pieces of military hardware, including fighters, helicopters, and tanks. The PRC’s Minister of Defense commented that the exercise was designed to deepen mutual trust and cooperation in the field of defense and security among SCO member states.

Maritime

Beyond continental Eurasia, China’s participation in ASEAN summits and the East Asia Summit also provides opportunities to influence regional security policy, especially in the maritime domain. As early as 2002, China and ASEAN identified non-traditional security issues—primarily anti-drug smuggling, counterterrorism, and counterpiracy—as areas of possible cooperation. Despite this pledge, implementation of this coordination was slow to start. Consultative mechanisms were irregular, poorly institutionalized, and generally relegated to case-specific cooperation between law enforcement agencies.

When China did accede to regional security agreements, such as the landmark 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, it opted for a path of selective enforcement, still choosing to build and militarize artificial land features in the South China Sea. In 2012, China’s Defense Minister attended the ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting (ADMM) and participated in an inaugural China-ASEAN ADMM. This increased contact and coordination resulted in October 2018’s inaugural China-ASEAN maritime exercise, which incorporated all ten ASEAN nations.

EMERGING ALIGNMENTS?

As the depth and breadth of China’s security, diplomatic, and economic partnerships continue to expand, and China seeks to project its comprehensive national power in new ways throughout the world, a robust debate has emerged within China’s academia about the nature and structure of the country’s security partnerships. Given the PRC’s dogmatic opposition to formalized security alliances, the depth and extent of China’s security partnerships can often prove opaque. While alliances are operationally a partnership between two militaries, the decision to enter into, and maintain, an alliance is a fundamentally political decision. Perhaps, the “new type of international relations” Beijing is seeking has space for an “aligned security partnership with Chinese characteristics.”

In tandem with the emergence of the “Chinese Dream,” researchers within mainland China have begun to explore alternate possibilities for a distinctly Chinese approach to regional security arrangements. In 2012, Nankai University Professor Liu Feng argued that the emergence of China’s partnership network provides an opportunity for China to move beyond its historic non-alignment framework and pursue coordinated diplomatic, economic, and security policies with states on its periphery. Scholars such as Zhou Fangyin have noted the need for China to promote the construction of new regional security mechanisms in response to the “negative role” that the United States alliance structure plays in Asia. Building on Zhou’s work, Professors Liu Bowen and Fang Changping document a potential model in which China expands its “partnership diplomacy” through the integration of existing bilateral economic and security ties to create a network of relationships capable of systematically favoring China’s regional security interests. Viewed together, it is clear that Chinese scholars have begun to think about alternative security and alignment mechanisms that China can pursue with states on its periphery.

Given that flexibility is a hallmark of China’s historic approach to international relations, the evolution of China’s security partnership diplomacy will be far from clear-cut, potentially spanning multiple categories without clear modalities underpinning Beijing’s outreach. However, as Chinese global influence and power projection continues to expand, the CCP will be forced to balance its long-standing ideological opposition to formal alliances and entanglement fears, with the real dividends derived from security partnerships.

INTEGRATING ELEMENTS OF NATIONAL POWER

Undoubtedly, the era of Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power has ushered in a globally-oriented China focused on increasing the depth and breadth of its international partnerships. Although China’s institutions have become increasingly international in focus over the past 15 years, Xi’s ascension marks the first time expansion of China’s role in the world has been elevated to a top CCP priority. While the public face of China’s expansionist tendencies is defined by the near-mythical “Belt and Road,” underneath the surface-level layer of propaganda, China’s leadership is contending with the real challenge of designing modalities and frameworks to wield comprehensive national power in a coordinated fashion. The PRC’s growing economic prowess is enabling Beijing to pursue a “China-first” development model, while simultaneously depicting interactions as “South-South Cooperation.” The PLA’s operations, joint exercises, and arm transfers have increased in sheer quantity and scope.

In totality, Xi’s China is defined by expansive global ambitions underwritten by limited domestic opposition, a capable military, aggressive diplomatic agenda, and diversified economic toolkit designed to induce and coerce. As China’s security and economic objectives become increasingly intertwined, Xi and the CCP’s ability to effectively integrate and deploy these varied levers of national power, thereby creating greater alignment with its growing number of partners, will be a key determinant of China’s effectiveness as a global power.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Comprehensive national power with Chinese characteristics: Regional security partnerships in the Xi era

January 22, 2019