Applying to college is anything but simple. In fact, over half of students rank college applications as their most stressful academic experience.

The typical application process is a gauntlet that involves several steps beyond just filling out an application form. Students must manage various deadlines across multiple portals, submit resumes, write essays, coordinate letters of recommendation, and request test scores and transcripts. This complexity keeps many talented and eligible students from applying and enrolling in college. Even “small” barriers like completing a second application, paying to send a test score, and verifying financial aid information are enough of a discouragement to prevent college-intending students from ultimately enrolling.

What’s more is that not all students experience these barriers in the same way. These frictions in the college application process loom larger for students of color, those from low-income backgrounds, and those who will be the first in their family to enroll in college. This means complexity in the college application process contributes to inequality in college enrollment.

This has led many to ask: Why do students need to apply to college at all? In reality, the vast majority of students attend colleges that accept the vast majority of applicants. That is, nearly one-third of students attend open-access community colleges, and another 56% attend four-year institutions that accept at least three quarters of their applicants. For most students, this means college applications – at least, those equivalent to the ones required by the most selective universities – are largely unnecessary.

New evidence has helped identify those who are most disadvantaged by the current college application process and shed light on emerging strategies to reduce the negative impacts of applications on students’ college-going behaviors. In this post, we review two important areas of research – on students who start applications but do not submit and direct admissions.

A quarter of students start a college application but never hit submit

First, we examined data on 1.2 million high schoolers to explore who starts, but never completes, a college application. We found that nearly 300,000, or about one-quarter of students in our sample, left their applications uncompleted. These “non-submitters” showed an interest in college opportunities by starting an application and making progress but ultimately did not submit the application before the end of their senior year.

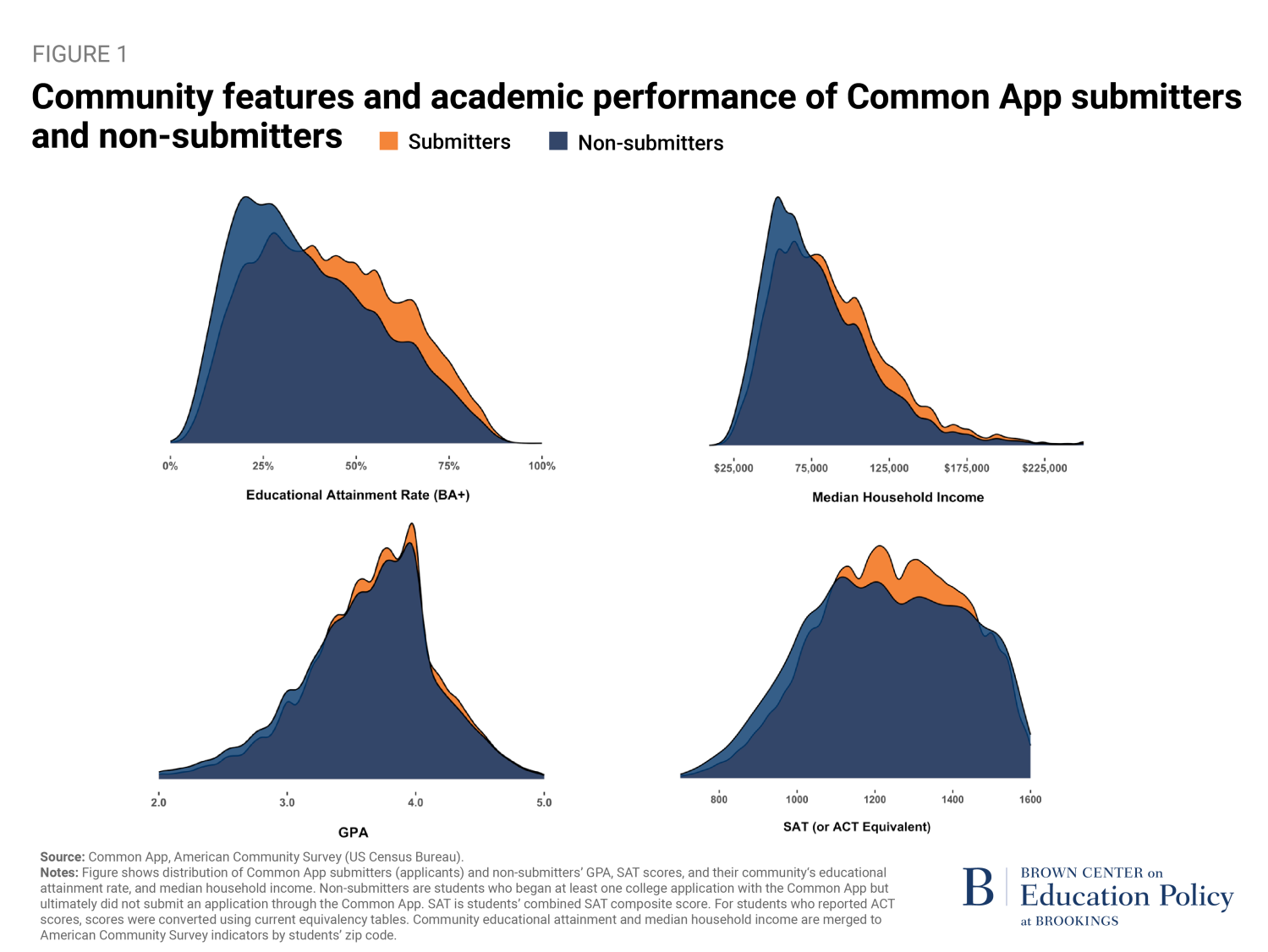

Black and Hispanic students, students whose parents did not hold a bachelor’s degree, and students enrolled in rural and Title 1 high schools were overrepresented among non-submitters. Additionally, students living in communities with lower educational attainment (the share of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher) and lower median household incomes were the least likely to submit a college application.

These non-submitters, however, were just as academically qualified for college. They had similar GPAs and ACT/SAT scores as those who ultimately submitted an application. These descriptive differences show that even academically well-prepared students can succumb to complexities in the college application gauntlet.

The study also found that completing the application essay was one of the most predictive factors in whether a student ultimately applied. Students who completed the essay were 50% more likely to submit the application than those who did not. It may be the case that students likely to apply anyway typically complete the essay or that the essay represents a significant barrier for prospective applicants – regardless of mechanism, these results have led others to renew calls to end college essays altogether.

However, rather than making some of these piecemeal adjustments to the application, like removing the essay, many states, institutions, and nonprofit organizations are experimenting with ways to eliminate the use of applications in the college-going process. Our research clearly shows that the likelihood of completing a college application varies by what a student looks like, where they grow up, and whether their parents went to college. So, instead of attempting to equalize application completion rates across these groups with strategies like college coaching or college application workshops, a new policy response is to get rid of the application altogether.

Many states and institutions are doing away with college applications

To date, at least 10 states and hundreds of colleges and universities have begun “direct admissions” programs. Rather than asking students to apply to college, direct admissions programs instead proactively admit them using data like their GPA and ACT/SAT scores. Without ever applying, students receive an official acceptance letter alongside personalized information on how to “claim their place” and enroll in college. No essays, no letters of recommendation, and no application fees.

In a recent chapter included in a new edited volume Rethinking College Admissions (Harvard Education Press), we discussed the design of direct admissions programs and what makes them unique from the traditional application process. The best practices of a direct admissions program are:

- Proactive: Simple and personalized information is sent directly to students.

- Guaranteed: A college opportunity is a “sure bet” for students. They are guaranteed admission.

- Universal: Every public high school graduate receives at least one postsecondary option after high school.

- Simple and transparent: Students are admitted based on clear guidelines and are given simple steps to enroll.

- Personalized: Students receive personalized information on their college options; not generic information.

- Low-cost: Direct admissions is free for students (no application fees) and low-cost for states and institutions since the policy uses existing data.

- Trusted adults: Includes parents and high school principals and counselors.

Well-designed direct admissions programs also typically shorten the timeframe of the college search and application process by notifying students of their guaranteed college options earlier in their senior year. Alerting students to postsecondary options early allows for them to explore these college options and complete other necessary steps, like applying for financial aid.

Considered together, these features simultaneously reduce the complex steps students must follow to apply to and enroll in college while also reducing uncertainty about whether they will be admitted. Reducing complexity and uncertainty in other aspects of college-going – like streamlining the FAFSA, sending up-front information on financial aid, and otherwise standardizing admissions and guaranteeing prices – has been shown to raise overall college enrollment levels and reduce inequality in who enrolls.

Barriers to enrollment remain, even after streamlined applications

We evaluated the impacts of the first statewide direct admissions program. Direct Admissions Idaho began in fall 2016 and automatically admits all high school students to all of the state’s public and some private institutions. We found that the program increased first-time undergraduate enrollments by 4% to 8% on average (50 to 100 students per campus) and increased the enrollments of in-state students by approximately eight percent to 15% (80 to 140 students). These enrollment gains were concentrated among those two-year, open-access institutions where all students were directly admitted. We did not, however, observe changes in the enrollment of low-income students, likely due to the fact that direct admissions does not include additional financial aid. Affordability remains a large barrier to enrollment for many students.

We also researched the impact of direct admissions on students’ application and enrollment behaviors at four-year colleges with a large-scale experiment involving over 35,000 students across four states. The team partnered with six universities who committed to proactively admit and waive application fees for a specified number of in-state high school students who exceeded a given GPA threshold, ranging from 2.70 to 3.30 depending on the institution. Working with the Common App to observe students’ high school GPAs, the team randomly assigned some students to receive direct admissions to one or more in-state universities and the rest to a business-as-usual, standard application process condition.

Students in the treatment group received a personalized letter that informed them of their admission, described the program, shared information on financial aid, and detailed the steps they needed to follow, which included completing a simplified form (not a full application) to “claim their place” and enroll in the institution. These students were 2.7 percentage points (or 12%) more likely to submit this form (compared to their peers submitting full applications), with larger impacts for racially minoritized, first-generation, and low-income students. Students were also more responsive to these automatic offers from larger, higher-quality institutions as measured by undergraduate headcount and six-year graduation rates.

However, students in the treatment group were not more likely to ultimately enroll in college. In a series of interviews and focus groups with recipients, affordability was cited as another barrier to access. One administrator shared: “We had quite a few students who deposited, who committed to us, but when they received their bills in July, they realized that [our university] wasn’t affordable for them, even after taking out the max in student loans. It definitely made us realize that we need to make a significant investment in need-based aid.”

Simplifying the college application process is just one step toward equalizing opportunity

Given the benefits of higher education for individuals, communities, and society at large, equalizing educational attainment and economic mobility is a critical policy goal. However, complexity and uncertainty present at every step along the college-going pathway reduce the likelihood that many students apply and enroll. Students also come to this process on unequal footing – with various levels of financial, social, and cultural capital they can rely on to navigate it. These two different factors combine to create inequality in college access.

Simplifying the college application process is one necessary but still insufficient way to broaden access to higher education. In tandem, we must also consider other barriers to admission and enrollment, including constraints on students’ ability to afford college. In the wake of recent Supreme Court rulings on college admissions, many states and institutions are seeking strategies to increase diversity and opportunity in higher education. Simplifying or eliminating college applications is one promising step.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).