This chapter is part of USMCA Forward 2025, which focuses on areas where deepening cooperation between the United States, Mexico, and Canada can help advance key economic and national security goals.

The United States, Canada, and Mexico have increasingly prioritized critical minerals as essential components of economic security, clean energy transitions, and advanced manufacturing. They acknowledge the need to develop critical mineral mining and processing capacity to reduce dependence on China and create more resilience in defense, energy, and digital economy supply chains. For the U.S., cooperation with Canada and Mexico in these sectors is paramount to achieve its supply chain diversification goals. The USMCA can provide both a forum and legislative framework to strengthen critical minerals cooperation.

The United States, Canada, and Mexico have increasingly prioritized critical minerals as essential components of economic security, clean energy transitions, and advanced manufacturing.

In the United States, Republicans have highlighted that critical minerals will be a top priority for the incoming Trump administration. This follows on the policies of the first Trump administration, which already strongly prioritized expanding the domestic mining industry to reduce U.S. reliance on China. The Biden administration also recognized the importance of critical minerals in building American competitiveness in downstream sectors such as batteries, semi-conductors, and other energy, defense, and digital economy applications. In support of developing domestic critical mineral capacity, the Biden administration allocated several billion dollars to enhancing domestic extraction, processing, and recycling of critical minerals, aiming to reduce reliance on foreign sources.

Mexico and Canada have also clearly recognized the importance of critical minerals for digital and decarbonization technologies. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has emphasized the importance of lithium and copper for electric vehicle production and is working to position itself as a key supplier of critical minerals. The Trudeau government’s multi-billion Critical Minerals Strategy is intended to help bring that objective forward by allocating funding to expand critical minerals mining capacity and support the development of Canadian supply chains in processing and recycling.

Despite the very clear prioritization of critical minerals security to bolster competitiveness, there remains a need for more robust policy measures and intergovernmental cooperation to diversify and onshore critical mineral supply chains. This underlines the importance of increasing collaboration through the USMCA. While tensions with respect to Chinese investments in Mexico in downstream sectors such as batteries and EVs will need to be addressed, prioritizing USMCA cooperation on upstream and midstream critical mineral supply chains can help kickstart a new era of North American collaboration. For that to be successful, efforts will have to go beyond rhetoric and address structural dependencies on China for critical minerals and batteries. This includes by promoting impactful trade and investment frameworks bilaterally, through the USMCA, and via the Minerals Security Partnership that can facilitate the financing and development of resilient and responsible critical mineral supply chains across North America.

Policymakers may very well find increasing support with the broader public, as the public’s understanding of the necessity for diversifying and onshoring critical minerals supply chains grows. For example, in the U.S., a recent survey revealed that 83% of so-called opinion leaders1, which included a bipartisan majority, consider expanding domestic mining to access mineral resources an important or top priority for policymakers. This shift in awareness is driven by recognition of the critical role minerals play in sectors such as healthcare (71%), semiconductors (69%), and defense (67%) and signals a slow but discernible shift in public perception toward the strategic importance of securing domestic supply chains. This can ultimately help provide backing to more USMCA cooperation on critical mineral supply chains.

Why USMCA cooperation on critical minerals is essential to expanding domestic capacity

The U.S., Canada, and Mexico face similar challenges when it comes to expanding domestic mining and refining capacity. One challenge is that the U.S., Mexico, and Canada, like the rest of the world, is deeply reliant on Chinese processing capacity of critical minerals. To use critical minerals in downstream sectors such as defense, developing digital and clean energy technologies, these minerals need to be processed until the highest possible purity levels, often at 99.9999% purity. Today, China dominates mineral processing for several critical minerals. This means that reducing dependence on China for critical minerals will require large investments into processing capacity, as well as developing the technological know-how and skilled workforce.

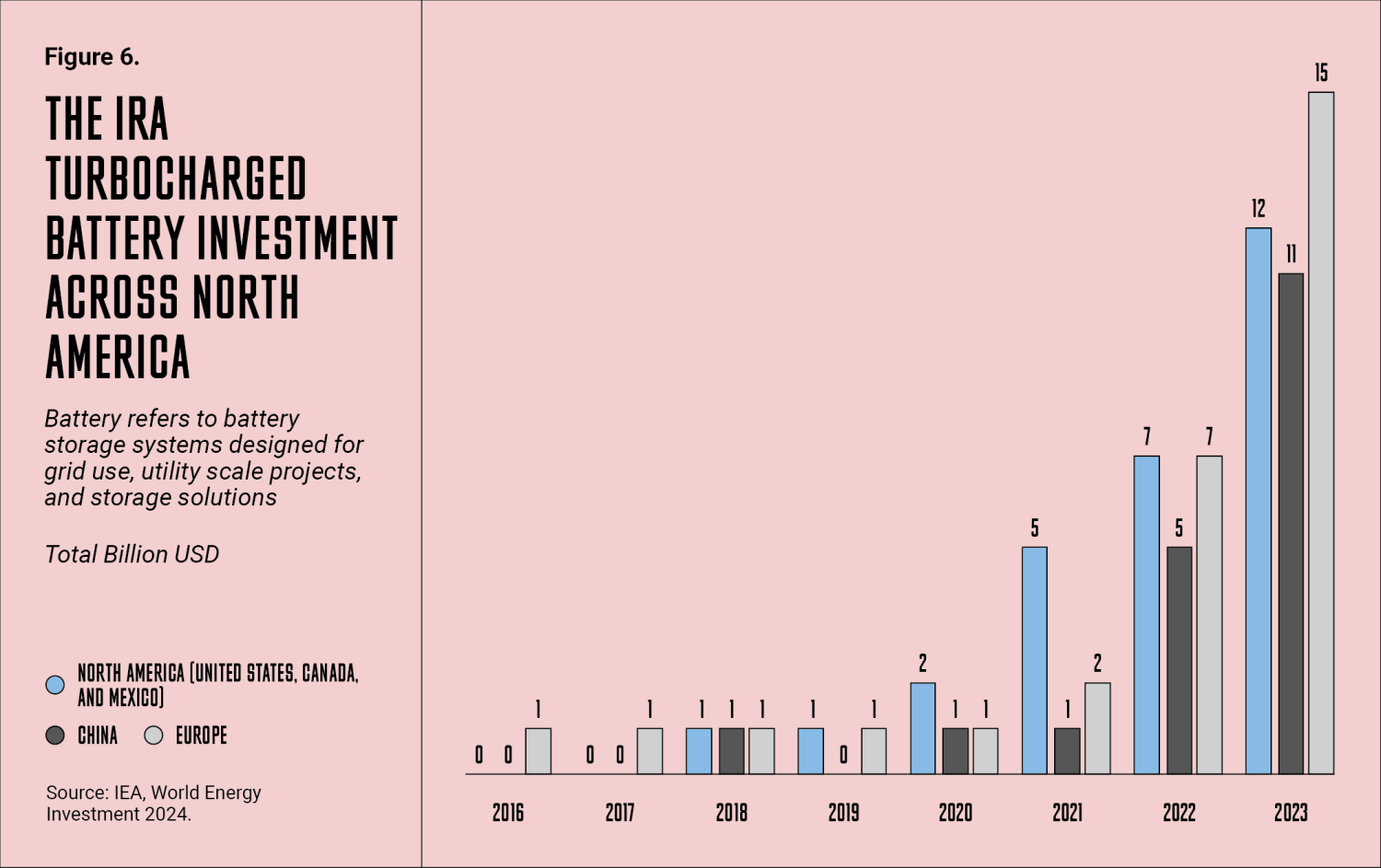

A second challenge is that the U.S., Mexico, and Canada need secure access to affordable critical minerals (raw and processed) to bolster the North American competitiveness of downstream industries. On the one hand, this includes well-established, highly innovative sectors such as lithium-ion batteries, EVs, and semiconductors. Supported by the IRA and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, the U.S. has received over $110 billion in EV and battery investments, of which 92% flowed to Republican-led states, and the development of this so-called battery belt is expected to remain strong in the next few years with 160 GWh of new battery manufacturing capacity expected to be added in 2025. In total, the North American EV market is expected to grow from $62 billion in 2022 to around $230 billion by 2030, including $53 billion in Mexico and $13 billion in Canada.

While it is difficult to pinpoint how much of that expected investment in Mexico and Canada is due to its own policies or its engagement with the U.S. via the USMCA, the fact the U.S. IRA tax credit for EVs stipulates that the vehicles need to be assembled in North America and the batteries in North America or U.S. FTA countries, extends those IRA subsidies to Canadian and Mexican producers.

The U.S., Canada, and Mexico also need to increase resilient supply chains of critical minerals for next-generation technologies in which North America still holds innovation and tech development competitiveness vis-à-vis China. This includes technologies such as iron nitride magnets, lithium-sulfur and lithium-metal batteries, silicon-anode, sodium-ion and iron-air flow batteries, advanced conductors for power grids, and perovskite solar cells, to name a few. Many of those next generation technologies are mineral-intensive as well, and so it is in the interest of the three governments to start securing mineral supply for those novel technologies early on, much like China did during the last decade and a half for the current generation of lithium ion battery chemistries.

On the supply side, USMCA countries hold significant and often complimentary roles with respect to mineral reserves and production. In terms of reserves, USMCA countries are largely complementary. The U.S. holds significant global reserves in Molybdenum (23%), Tellurium (11%), Lithium (4%), and Silver (4%). Mexico from its side holds reserves in Silver (6%) and Zinc (7%). Canada adds to that regional outlook with significant reserves of Niobium (9%), Selenium (6%), Titanium (4%), and Lithium (3%). For other minerals, the countries each hold smaller shares of global reserves, but they often produce more. If critical minerals security of supply is truly a strategic goal, then it is important to protect that production and facilitate, at the local, national, and regional level, responsible expansions where feasible.

In terms of production, the complementarity is largely similar. The U.S. produces significant global shares of Berrilyum (56%), Molybdenum (14%), Zirconium (7%), Zinc and copper (6% each), and Silver (4%). Mexico produces large amounts of Silver (24%), Molybdenum and Zinc (6% each), Cadmium (5%), Barium (4%), and Copper (3%). Canada is a big producer of Niobium, Cadmium, and Palladium (8%), Nickel, Aluminum, Tellurium, and Indium (4% each), Selenium (3%), and Copper (2%).

|

US (%) |

M (%) |

Ca (%) |

Total (%) |

Energy transition applications |

Defense applications |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Beryllium |

55.9 |

- |

- |

55.9 |

Lightweight alloys for aerospace |

Missile guidance, radar systems |

|

Silver |

4 |

24.2 |

- |

28.2 |

Solar panels, electronics |

Electronics, high-conductivity wiring |

|

Molybdenum |

13.7 |

6.1 |

0.3 |

20.1 |

Wind turbines, hydrogen production |

Aircraft engines, armor |

|

Cadmium |

- |

5.2 |

8 |

13.2 |

Batteries (Ni-Cd) |

Elecronics, optics |

|

Zinc |

6.1 |

6 |

- |

12.1 |

Corrosion-resistant coatings, batteries |

Alloys, protective coatings |

|

Copper |

5.6 |

3.4 |

2.4 |

11.4 |

Wind turbines, solar panels, wiring |

Electronics, communications |

|

Niobium |

- |

- |

8 |

8 |

High-strength steel for turbines |

Jet engines, structural components |

|

Zirconium |

6.9 |

- |

- |

6.9 |

Nuclear reactors, hydrogen storage |

Heat-resistant alloys |

|

Aluminum |

1.3 |

- |

4.1 |

5.4 |

Lightweight materials for electric vehicles, solar panels |

Aircraft, armor, lightweight vehicles |

|

Nickel |

0.5 |

- |

4.4 |

4.9 |

Batteries (electric vehicles, grid storage), alloys |

- |

|

Platinum |

1.7 |

- |

3.1 |

4.8 |

High-strength alloys, armor plating |

Electronics, fuel cells |

|

Tellurium |

- |

- |

4.1 |

4.1 |

Solar panels (thin-film), thermoelectrics |

Electronics, infrared detectors |

|

Indium |

- |

- |

3.9 |

3.9 |

Solar panels (CIGS), electronics |

Display technologies, sensing devices |

|

Barium |

- |

3.8 |

- |

3.8 |

Drilling fluids, electronics |

Explosives, signal flares |

|

Selenium |

- |

- |

3.3 |

3.3 |

Solar panels, thermoelectrics |

Electronics, optoelectronics |

Source: Critical Materials Monitor 2024 and author consultations with industry

Current USMCA engagement on critical minerals

U.S.-Canada cooperation so far could be a blueprint for North American cooperation on critical minerals but would need further strengthening on the policy side of the equation. While political cooperation has accelerated in recent years against a backdrop of increasing local demand for critical minerals, heightened geopolitical tensions, and the objective of both governments to increase security of supply for strategic industries such as defense, clean energy, and semiconductors, the scope and scale of U.S.-Canada governmental cooperation remains limited and insufficient to address these supply chain challenges. Extending cooperation and leveraging USMCA to facilitate the needed investment, develop common standards, and reduce regulatory barriers, should be the focus for all three governments going forward.

There is no doubt that U.S.-Canada business engagement is both wide and deep. Under the framework of the USMCA, the two countries serve as primary trading partners for critical minerals. Canadian exports of minerals (including non-critical minerals like iron ore) were valued at $61 billion in 2022, of which $41 billion or 67% was exported to the United States. Similarly, the first trading partner of U.S. mineral exports of $122 billion in 2022 was Canada, at $31 billion, or 25%. There is also extensive cross-border investment in critical minerals. For example, there are approximately 323 Canadian companies that have invested over $45 billion in the U.S. mining sector (including non-critical minerals) and 120 Canadian companies have invested over $11 billion in Mexico.

The United States, Canada, and Mexico have increasingly prioritized critical minerals as essential components of economic security, clean energy transitions, and advanced manufacturing.

The overarching strategy for U.S.-Canada cooperation on critical minerals was articulated in the U.S.-Canada Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals in January 2020. It is notable for its scope, but results have remained largely aspirational, aside from some significant innovations (see below). The strategy helpfully identifies the multi-sectoral raison d’être for critical minerals cooperation as it links critical minerals to industrial development, innovation, defense supply chain resilience, information sharing, and multilateral cooperation. Having that multi-sectoral approach that encompasses the digital economies, clean energy, and national defense is essential, so the strategy should be applauded for that. However, the implementation of this strategy has been incremental and fragmented. While both governments have made public commitments to advancing these priorities, the absence of measurable benchmarks or timelines limits the ability to assess the effectiveness of this initiative.

So far, actual investment, which the industry agrees is what will be needed to develop an onshore critical mineral supply chains, have remained far too limited. Both under Trump and Biden, U.S. Government investment through the Defense Production Act (DPA) Investment Program has been marginal relative to the scale of the supply chain challenges. Several U.S. Government and Government of Canada co-investment initiatives have been announced into expanding cobalt and graphite production. For instance, Fortune Minerals Limited received $6.4 million from the United States, supplemented by $5.6 million from Natural Resources Canada, to support cobalt supply chain development. Similarly, Lomiko Metals Inc. secured $8.3 million from the U.S. government, with an additional $3.6 million from Canada, for graphite production. Other projects, including those led by Electra and Nano One Materials, have received comparable funding for cobalt and lithium iron phosphate technologies. While these investments represent progress, and while government co-investment can indeed help to unlock more private capital, the scale remains far too small when juxtaposed against the magnitude of capital required to establish resilient and integrated critical mineral supply chains. The focus on cobalt and graphite, while essential, also underscores that the collaboration is more focused on existing battery supply chains than potential future mineral vulnerabilities.

Another area for cooperation on critical minerals is data sharing in the form of unified geological survey data. This was identified as a priority by the three presidents in the North American Leaders’ Summit in 2023, which recognized the need to expand North American critical minerals resource mapping to collect details on resources and reserves through more in-depth collaboration between the Geological Surveys of each country. This ultimately led to unification of critical minerals data by Canada, the U.S., and Australia. While it is too early to judge on the practical utility, the standardization of information on resource potential can surely help advanced analytical techniques and AI applications in mineral exploration, and Mexico’s future involvement could help expand the yield of exploration initiatives.

What is needed to accelerate USMCA cooperation on critical minerals supply chain?

Four immediate priorities arise for USCMA cooperation in the field of critical minerals. The upcoming USMCA review should serve as the platform to revisit how USMCA can support the development of critical mineral supply chains across North America. First, USMCA commitments can be used to align regulatory frameworks to create a more supportive environment for critical mineral mining and processing. This could include harmonizing regulations across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico to reduce bureaucratic barriers, improve cross-border investment conditions, and enable the development of integrated North American supply chains. Regulatory alignment can also help address policies that undermine investment like those in Mexico, where restrictive policies such as lithium nationalization and proposed bans on open-pit mining hinder cross-border investment and undermine critical mineral supply chains.

A second important issue for the negotiating table is the impact of various domestic policies on cooperation with USMCA partners. For example, Canada is recognized as “domestic” under the U.S. Defense Production Act, and under the Inflation Reduction Act’s EV credits. However, under certain supply chain and processing partnerships under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the “Buy America” provisions require domestic sourcing of constituent components including minerals for projects funded with federal funds, unless specific waivers are granted. Similarly, in the CHIPS Act’s support mechanisms to build out domestic semi-conductor material supply chains, and the IRA production tax credits for critical minerals refining, Canada is not automatically considered as domestic.

Extending cooperation and leveraging USMCA to facilitate the needed investment, develop common standards, and reduce regulatory barriers, should be the focus for all three governments going forward.

Third, USMCA cooperation can focus on stockpiling and building joint processing capacity, which is the true bottleneck in the supply chain and a threat for downstream sectors in USMCA countries. An analysis by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy shows that mineral acquisition for defense purposes would cost north of $6 billion today, whereas mineral acquisition for a stockpile that is able to offer some form of market stability would easily cost more than $40 billion. These are large amounts that showcase the need for burden-sharing among allies. Even with stockpiling, the remaining challenge is processing, where Chinese competitive advantages that were created with the help of state support now undermine the potential build-up of processing capacity elsewhere. Changing the status quo will require a multi-country approach, given the capital cost of processing facilities and given the fact that China’s advantage is not only state support, but rather the development of an integrated and highly standardized supply chain that has created large incumbents that are able to outcompete global counterparts even without state support. Acknowledging the national security implications of this reality and the need to maximize economies of scale to stand a chance of competing with Chinese players should be recognized in the USMCA competitiveness committee and leaders’ declaration alike.

Fourth, USMCA can provide a platform to discuss the updating of the Defense Production Act to streamline approvals, increase project capacities, and raise budget cap. As mentioned, historical data indicates that DPA funding for such projects has been modest, often constrained by political sensitivities, particularly when involving foreign entities such as Canadian companies. By simplifying co-investment requirements and increasing funding allocations, the U.S. could catalyze larger joint ventures with allies like Canada and Australia, who are already recognized as domestic partners under Title III. This would align funding mechanisms with the scale of the challenge and enabling North America to better compete with China’s dominance in mineral supply chains.

Currently, under Title III of the DPA, projects up to $50 million require congressional notification, while those exceeding this threshold necessitate explicit congressional approval. This process can introduce delays and uncertainties, particularly for larger-scale projects critical to national security. To address this bottleneck, revisions to the DPA should include raising the budget cap for expedited approvals, allowing more projects to bypass lengthy congressional approvals. For example, increasing the threshold to $150 million for specific critical mineral projects of acute national security concern could significantly enhance the Department of Defense’s ability to quickly invest in strategic projects while maintaining transparency and oversight through Congress’s notification process.

-

Footnotes

- For the poll, opinion leaders were defined as employed U.S. adults age 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher, an income of $75,000 or more, who are registered voters, and actively engaged in civic activities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).