Philippe Le Corre argues that the global leadership void left behind by the United States and President Trump will not be filled so easily.This piece was originally published in the Nikkei Asian Review.

Chinese state media have recently been hailing the prospects for greater cooperation with Europe as U.S. President Donald Trump’s pullback from global affairs gains speed. But can Beijing and Brussels really join forces to pick up the slack?

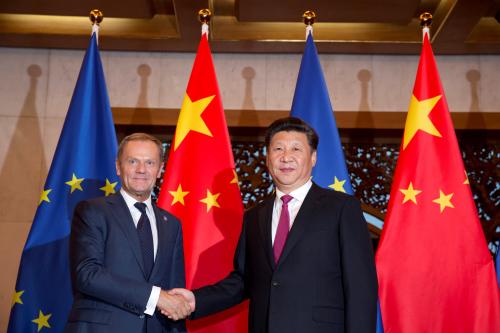

January saw the conjunction of two remarkable events: Trump’s inauguration as president and Chinese President Xi Jinping keynote speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Trump’s dark viewpoint on globalization contrasted strongly with the positive notes struck by Xi.

These events and the chaotic first two months of the Trump administration have led many opinion leaders in China to see closer ties with Europe as a viable strategy. Considerable obstacles however remain for a new dynamic on global issues to work.

The growth of populism in several Western countries and the future of the European Union as an economic entity worry many Chinese scholars. Both matter a lot to Beijing, which is promoting its economic and strategic agenda, under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative, with a clear aim at the European consumer market. With 420 million people, it remains China’s most important market. The EU is also a major recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment, which reached $46 billion last year, up 90% from the previous year, according to law firm Baker McKenzie.

The result of last year’s U.K. referendum on EU membership came as a shock to Chinese observers. Many of them are now wondering what the impact of Brexit will have on the future of the EU.

Election issues

Several Chinese think-tankers who must remain anonymous are asking whether far-right leader Marine Le Pen can become president of France as this could lead to a breakup of the EU and certainly a rise in import tariffs. If Europe as a single market were to fade away, this would be a terrible blow to the Chinese leadership’s pro-trade stance, especially at the time of so much uncertainty when it comes to U.S.-China relations with Trump and Xi preparing to meet for the first time. The policy community in Beijing was only partly reassured by U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s recent visit, which did not address any critical economic issue and focused on the Korean Peninsula.

Like its American counterpart, European public opinion has become more critical of global trade, also seeing China as one of the chief beneficiaries. Last May, the European Parliament passed a resolution against treating China as a market economy “because this would increase chances of populist movements in Europe, especially in France,” according to Reinhard Butikofer, a German member of the body.

During the first televised French presidential debate on March 21, Republican candidate Francois Fillon commented that China was the country benefiting the most from global trade and that “European companies should be better protected.” Centrist candidate Emmanuel Macron agreed.

Just like the almost-defunct Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreement with the U.S., China could well become a punching bag as a series of national elections proceeds in Europe.

Climate change

Some have argued that climate change could be a promising area for Sino-European cooperation. After all, Trump and many of his supporters-turned cabinet members have made statements against the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Some have bluntly denounced climate change as a “hoax.”

But it is far from certain that China would want to take over leadership on this issue alongside the EU. One leading expert in Beijing told me China is not in a position to do so as it copes with slowing economic growth and managing a difficult transition into a service-oriented economy. In addition, while China may have become more norms-conscious lately, it does not like international regulators overseeing its own commitments as shown by its resistance to an international arbitration court’s decision regarding the South China Sea.

Given the current global context, Beijing should adopt a cautious approach to Europe. The U.S.-China relationship is far from settled, and neither China nor Europe are prepared to publicize an “alternative vision of the world,” as a Chinese scholar put it. No one knows where transatlantic relations are going under Trump, but China assumes that Europeans and Americans will eventually become close again. Betting on a Sino-European axis is just unrealistic.

It is hard to imagine Europeans advocating a Sino-European partnership that would take the lead in creating a new world order without the U.S. China has indeed become a bigger player on the world stage and increased its role within the U.N., but it remains essentially self-centered and its diplomatic initiatives have all matched its own interests. In many parts of the world, China’s role has been essentially just economic. As for the EU, it has barely begun dealing with Brexit and is trying to figure out what the Trump administration actually wants when it comes to international relations.

Trade remains the key issue. China is an advocate of free trade, Premier Li Keqiang emphasized during his annual press conference on March 17. “We believe all countries need to work together to push it forward,” he said. “The world belongs to us all and we all need to do our part to make things better. We are open-minded toward the various regional trading arrangements, established or proposed, and welcome progress in them.”

This is not the message one hears from White House ideologues who are insisting on rebalancing America’s trade through “free, fair and reciprocal trade.” By reciprocity, they mean higher tariffs and sanctions for countries that do not “play by the rules.”

In a more subdued fashion, this view is increasingly shared by Europeans. On Feb. 13, economy ministers from France, Germany and Italy wrote to the European Commission to request a review of EU rules on inbound foreign investment amid concerns that technological know-how is leaking abroad. The ministers noted that even as a growing number of non-EU investors have been buying up European technologies to serve the strategic objectives of their home countries, EU companies often face barriers when they try to invest in such places. Many saw China as the obvious target, especially in Germany where scrutiny of Chinese investment in sensitive areas has been considered insufficient. Nevertheless, the German government last year blocked the acquisition of semiconductor manufacturer Aixtron by a Chinese company.

In Beijing, many are hoping that the first meeting between Trump and Xi will address the trade issue so that the crucial U.S.-China relationship can return to its normal course. The U.S. and China are competitive strategically, but need each other economically.

As for the Europeans, they are just too busy with their own elections to engage in any long-term discussions with China at the moment. None of the bloc’s “big four”- the U.K., Germany, France and Italy — are in a position to do so. Once new governments are in place in France and Germany in particular, they can engage with each other on how to deal with China as a major economic player and growing investor. They can then initiate a conversation with the Trump administration which might otherwise be tempted to pursue a bilateral “G2” relationship with Beijing that would only please China too much.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edBeijing-Brussels axis stands little chance

April 6, 2017