In the heat-stressed city of Atlanta, the South River Forest is one of the city’s four “lungs”—serving as a critical piece of climate infrastructure that cools surface temperatures, cleans the air, and prevents flooding. But for the past two years, the South River Forest has also been a site of contention and protest over what has become known as “Cop City”—a proposed $90 million, 85-acre police training center slated to destroy parts of forest and disproportionately impact residents of the nearby majority-Black neighborhood.

National coverage of Cop City has, understandably, tended to focus on police violence against protesters and arrests, charges, and accusations of domestic terrorism against organizers, which have alarmed civil rights advocates. However, focusing only on these boiling points can inadvertently obscure a larger picture: that the fight against Cop City is not a new one, nor is it confined to the city of Atlanta.

Instead, the Atlanta protests represent the latest struggle in a larger movement to combat generations of public policies that concentrate the harms of environmental discrimination (through zoning and land use) and criminal legal system involvement (through racially biased policing practices) in communities of color. Similar protests at the intersection of climate and criminal legal system injustice have occurred in Delano, Calif., Birmingham, Ala., Chicago’s Garfield Park, and communities impacted by carceral institutions nationwide.

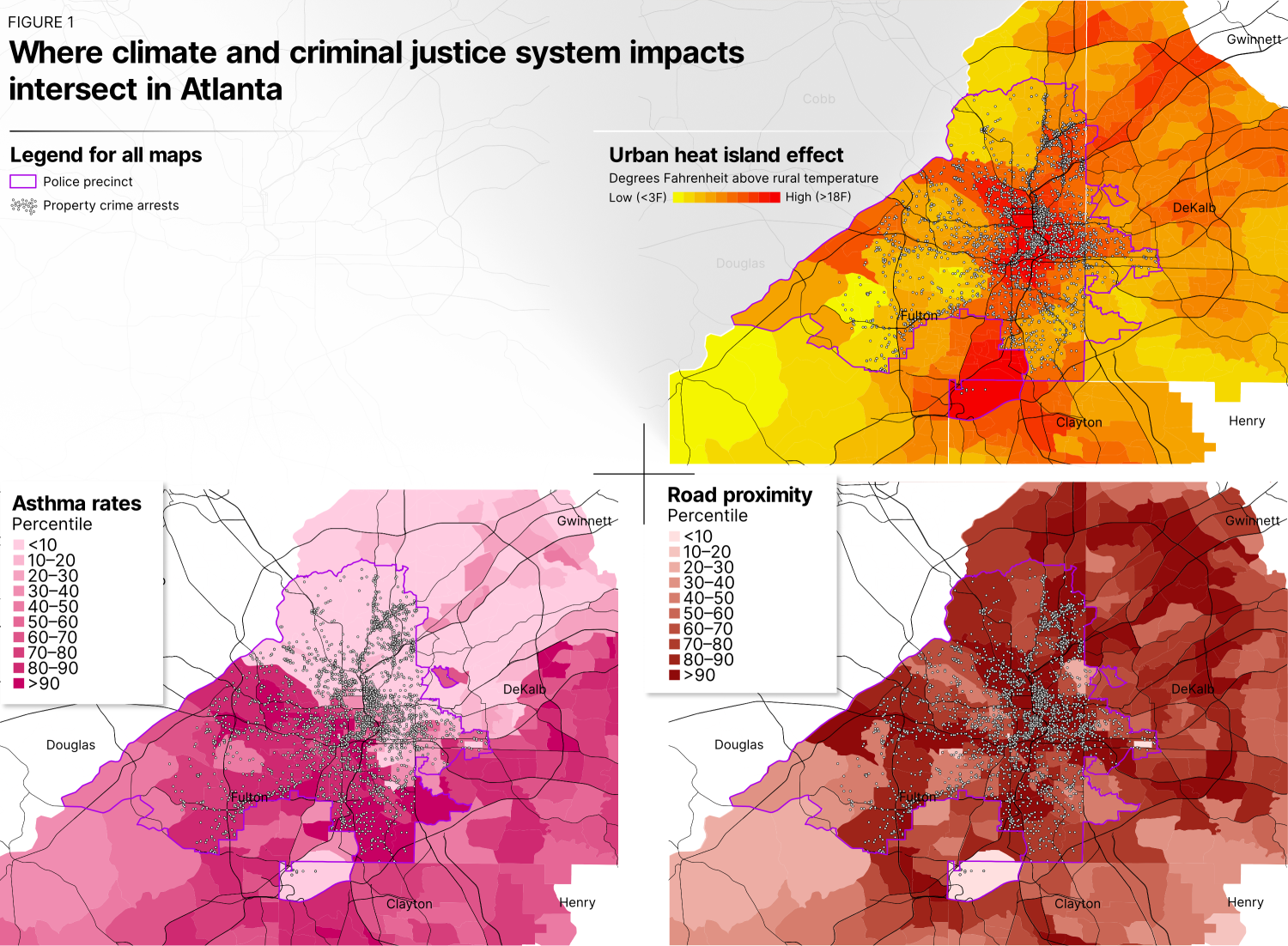

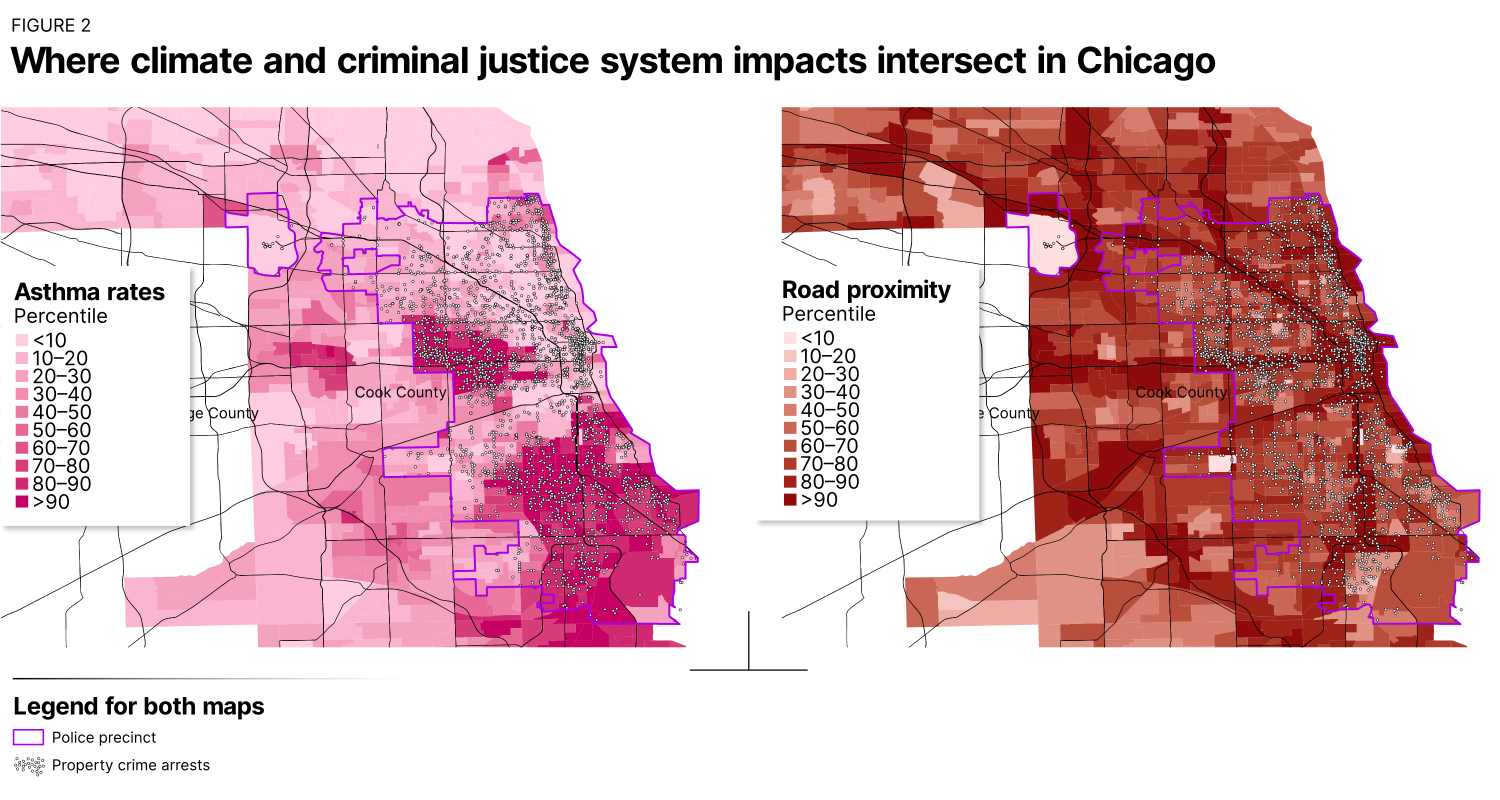

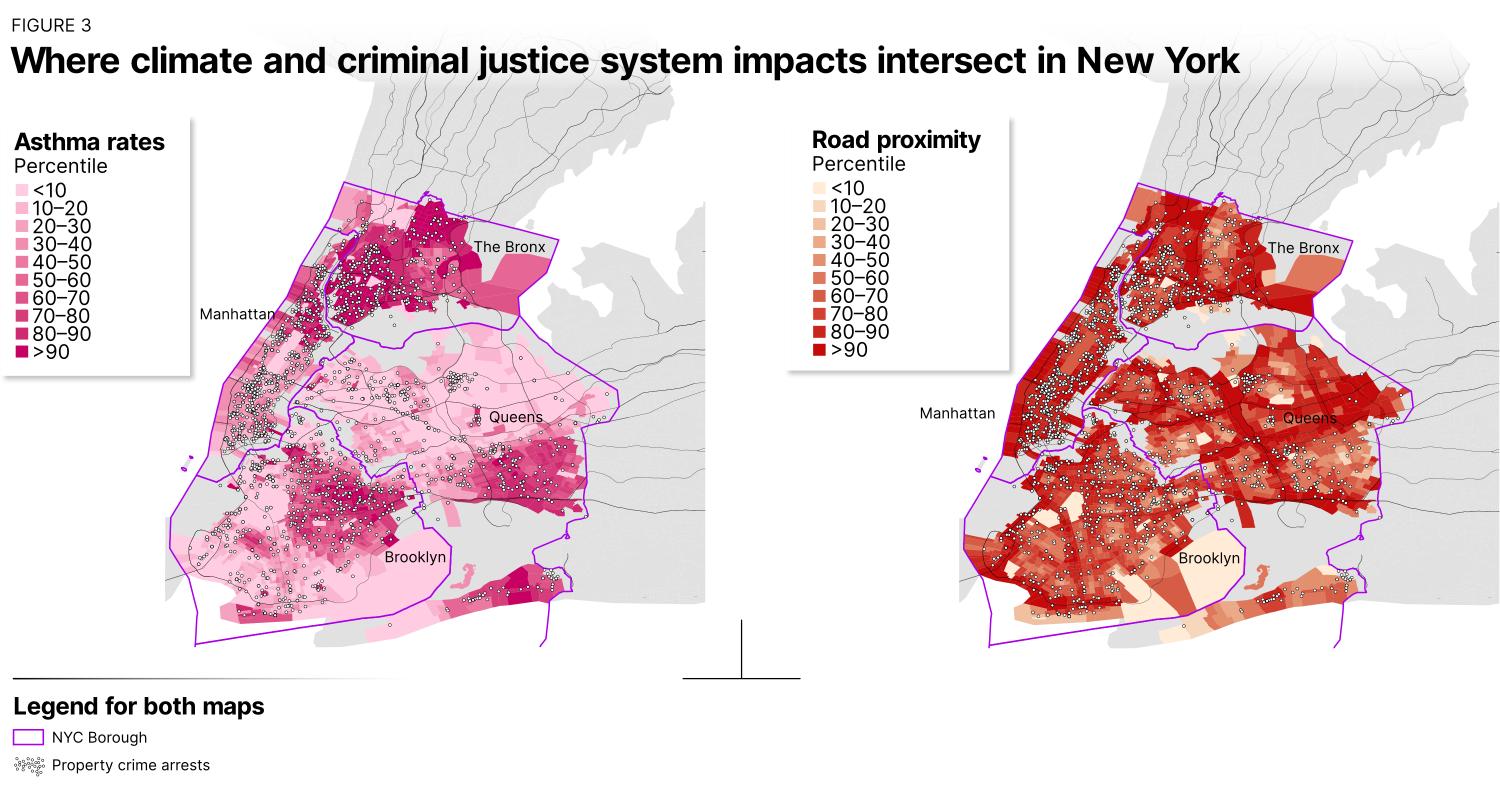

To ground the events unfolding in Atlanta in evidence and context, this report maps the social and environmental factors that render certain communities vulnerable to disproportionate climate and criminal justice system impacts. Using data from Atlanta, Chicago, and New York, we find that the same neighborhoods are disproportionately exposed to both climate impacts and higher rates of policing relative to other neighborhoods. We conclude with policy ideas to tackle these interconnected challenges with interconnected solutions rooted in community-level investments.

‘Forgotten places’ and ‘sacrifice zones’: Understanding the intersection between criminal and environmental justice

Historically, much of the research on the relationship between crime, criminalization, and climate impacts has offered individualistic interpretations focused on personal behavior and violence. For instance, scholars have used “temperature-aggression theory” to explain the relationship between heat and violent crime, arguing that higher temperatures make people more aggressive and irritable, and thus cause them to commit more crimes. Less attention has been paid to the structural causes that could render certain communities to be disproportionately exposed to both extreme heat and high rates of policing.

Looking across the often-siloed fields of criminal justice and environmental justice, the underlying structures behind the relationship become more evident. For instance, environmental justice scholars have used the term “sacrifice zones” to describe how zoning and land-use policies concentrate toxic pollutants and extractive industries in predominantly Black and Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods. In the criminal justice field, scholar and geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore has used the term “forgotten places” to describe how land-use and economic development policies similarly concentrate the harms of incarceration, environmental degradation, underemployment, and other indicators of disadvantage in communities of color.

Whether discussing the placement of industrial plants in the South Side of Chicago or the targeting of police raids in Louisville, Ky. neighborhoods experiencing gentrification, Black, Indigenous, and other people of color have been exposed to the brunt of climate injustice and criminal justice system exposure, while whiter, wealthier communities have been shielded from the worst of both.

There is a lack of political action, even amid rising risks

Despite academics and activists calling attention to the convergence between place, climate impacts, and carceral harms, the political will to address these issues—and importantly, the land-use, zoning, economic development, and criminal justice system policies that caused them—has been lacking.

Some argue that this political inaction stems from the fact that government institutions perceive disinvested communities of color as lacking the economic and political capital to fight back against extractive developments (including prisons). Indeed, in 2021, Atlanta’s City Council ignored more than 17 hours of public comments opposing Cop City, and did so again in 2023. The city is now challenging signatures collected to put a referendum on Cop City on the ballot through a controversial “verification” process that some have called disenfranchisement. Most recently, a new RICO indictment against 61 activists claiming the movement is a “criminal enterprise” has alarmed many free-speech and civil rights advocates.

Similar processes of community disenfranchisement occur in majority-Black communities nationwide. One recent example is in Flint, Mich., where the appointment of an emergency financial manager removed residents’ democratic recourse to challenge controversial decisions that were exposing citizens to unsafe water.

The increasing frequency of climate-related disasters means we are likely to see more conflict, harms, and deaths at the intersection of environmental injustice and the criminal legal system, undermining individual well-being and shortening life expectancy in communities of color. One recent example is the death of 19-year-old Caleb Blair, who was arrested after being denied entry to an air-conditioned store during a Phoenix heatwave in summer 2022, and subsequently died in police custody.

Methods

This piece examines the extent to which communities in three large U.S. cities (Atlanta, New York, and Chicago) are disproportionately exposed to both climate injustice and criminal legal system impacts such as higher rates of policing. Importantly, our research does not seek to determine a causal relationship between climate injustice and criminal legal system involvement, but rather shine a light on the structural factors (such as land-use policies and investment patterns) that may cause disparate exposure to both in the same neighborhoods.

Measuring climate injustice: We measure climate injustice using three indicators of vulnerability to extreme heat: urban heat island effects, asthma rates, and road proximity. We chose these indicators not only because of the increasing prevalence of extreme heat, but because of the place-based factors—such as access to green space and exposure to pollutants—that raise the likelihood an individual will be at higher health risks from extreme heat. Asthma rates and household proximity to roads, in particular, amplify the health risks of extreme heat and are deeply tied to public policies such as highway construction and the location of toxic sites in majority-Black neighborhoods. Moreover, higher temperatures produce a host of challenges for communities, including higher utility costs, public service strain, and premature deaths.

Measuring disproportionate policing: Collecting data on policing is notoriously difficult, let alone the extent to which certain communities are “over-policed”– which refers to when a disproportionate police presence in communities negatively impacts them (such as through unwarranted stops, high arrest rates for minor offenses, and acts of violence and/or aggression). This report measures disproportionate policing by analyzing data on arrest rates for nonviolent property crimes. We chose to focus solely on nonviolent property crimes—which tend to be lower-level offenses—because evidence indicates that such low-level offenses have been unfairly policed in majority-Black communities through racially targeted practices such as “stop and frisk,” and that this differential treatment is a red flag that a particular community is the target of unfair enforcement. Moreover, at the community level, impacts of arrests for low-level crimes are cascading—including job and income loss and family separation—while the evidence behind the effectiveness of policing low-level crimes is weak.

In Atlanta, New York, and Chicago, the same neighborhoods are exposed to disproportionate climate impacts and rates of policing

Our findings demonstrate a strong relationship between census tracts with greater vulnerability to climate injustice (as measured by exposure to extreme heat) and policing (as measured by higher rates of arrests for nonviolent property crimes). This shared vulnerability manifests differently in each metro area; in Atlanta, for instance, urban heat island effects were most correlated with arrests, while in Chicago and New York, asthma rates were most correlated. Yet each area shows a pronounced intersection between indicators of climate injustice and over-policing.

While all three cities we analyzed demonstrated a strong relationship between census tracts with higher heat island effects and higher rates of arrests for nonviolent property crimes, Atlanta—home to Cop City—stood out. For instance, Figure 1 shows that the Atlanta neighborhoods with the highest quantile of heat island effects had over 3.5 times the nonviolent property crime arrest rates than those in the lowest quartile (9.6 arrests per 1,000 compared to 2.1). Many of these neighborhoods, such as those in the Metropolitan Parkway corridor, also have a history of disinvestment and economic exclusion.

Asthma rates and proximity to roads—which shape a resident’s experience of extreme heat and renders them more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change—show similarly strong correlations in Atlanta (Figure 1). For instance, census tracts with the highest density of roads also had nonviolent property crime arrest rates 62% higher than the city as a whole (17.1 arrests per 1,000 residents, compared to 10.5 citywide).

Figure 2 shows similar trends in Chicago, with a particularly strong correlation between asthma rates and nonviolent property crime arrest rates. For example, in Chicago neighborhoods with the lowest quartile of asthma rates, nonviolent property crime arrests are 3.8 per 1,000 people; but in the highest quartile, they are 8.2 per 1,000.

Finally, Figure 3 shows these trends in New York, where asthma and arrest rates are highly correlated, particularly in the Bronx, southeast Queens, and northeast Brooklyn. Across the city, property crime arrest rates ranged from 8.1 per 1,000 people to 15.6 in places with the highest quartile of asthma rates.

While these correlations do not imply a causal relationship between climate injustice and disproportionate policing, they emphasize a clear overlap and point to the need to reform the policies and practices that enable both harms to concentrate in the same places.

Community-level investments can address both policing and climate injustices

After one of the hottest summers on record—and also one dominated by fears of rising crime—there is a significant need for local leaders to reevaluate how they allocate their land and resources to keep their constituents safe from crime, disproportionate policing, and climate harms.

While the structural reforms needed to repair the generations of policies that created “sacrifice zones” and “forgotten places” will take significant time, investment, and political will, cities can start now by protecting existing climate infrastructure assets and pursuing place-based solutions that have been shown to improve public safety, public health, and environmental outcomes in a relatively short timeframe.

Numerous community-level interventions to neighborhoods’ physical, economic, and civic infrastructure have been proven to improve both safety and environmental outcomes. For example, efforts to restore vacant and blighted land have been found to significantly reduce gun violence and can mitigate the effects of heat through increased shade and greenery. Increasing tree canopy also reduces crime and has obvious environmental benefits. City-funded programs such as grants for structural repairs to low-income housing have been shown to reduce violent crime and can improve climate resilience through weatherization or retrofitting schemes. Zoning reforms and creative placemaking initiatives also have significant positive impacts on community-level health and safety outcomes.

The decision of what cities value now has implications for what—and who—they will value in the future. Atlanta’s South River Forest, which regulates temperatures and provides residents with a critical source of climate resiliency, is an asset that benefits majority-Black neighborhoods in one of the most heat-stressed cities in the country. Destroying 85 acres of it despite public opposition is a choice with long-term consequences. And Atlanta is not alone in making these decisions, with cities from Newark, N.J. to Port St. Lucie, Fla. to Corpus Christi, Texas spending tens of millions of dollars on large new police training developments rather than investing in community-level interventions that can improve public safety, public health, and climate resilience in tandem.

As the future of the Cop City referendum hangs in the balance, it is critical to remember that instead of solving one problem (crime) by exacerbating another (climate injustice), cities have a plethora of evidence-based policies at their fingertips that can address the root causes of each through holistic, rather than siloed, approaches.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).