In collaboration with the Financial Times (FT), Eswar Prasad of Brookings and Aryan Khanna and Darren Chang of Cornell have constructed a set of composite indexes that track the global economic recovery. The Tracking Indexes for the Global Economic Recovery (TIGER) is also featured in the Financial Times. A version of this article appears in Project Syndicate.

The world economy faces sharply divergent growth prospects across various regions, as prospects of a uniform swift snapback from a dismal 2020 have become clouded. The latest update of the Brookings-Financial Times Tracking Indexes for the Global Economic Recovery (TIGER) reveals grounds for optimism about global growth prospects but also renewed concerns about impediments to a strong recovery. Vaccination euphoria and attendant hopes of a rapid, broad-based recovery have been tempered by a fresh COVID-19 wave sweeping through a number of economies, putting their growth trajectories at risk.

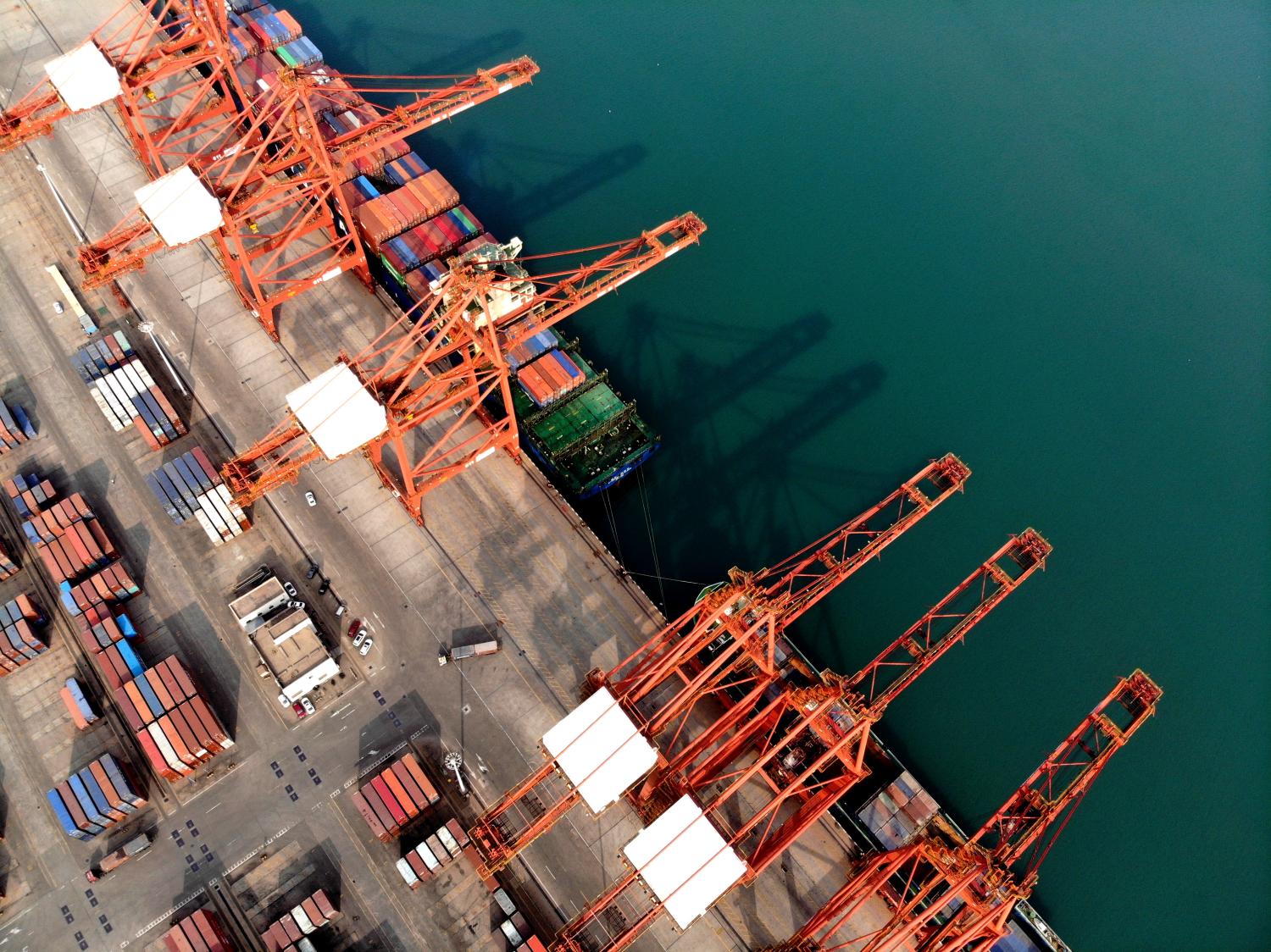

The U.S. and China are shaping up to be the main drivers of global growth in 2021. Household consumption and business investment have surged in both economies, along with measures of private sector confidence. Industrial production has rebounded in most countries, contributing to firming commodity prices and robust international trade. However, the U.S., China, and India are likely to be the only major economies (along with Indonesia and South Korea) that exceed pre-COVID-19 GDP levels by the end of 2021. In most other regions, the scarring effects of the 2020 recession on both GDP and employment are likely to be longer-lasting.

The U.S. economy is poised for a breakout year as massive fiscal stimulus, loose monetary policies, and pent-up demand power rapid GDP growth. Renewed consumer and business confidence have been reflected in generally strong consumption and business investment growth, while financial markets have continued to perform well. Labor market performance has been encouraging, although progress in job growth and unemployment reduction has been uneven in recent months.

Click a country name below the Composite Index to view charts for the main TIGER indexes by country.

Separating the imminent phantom increase in inflation (due to base effects from a weak 2020) from underlying wage and price pressures will complicate monetary policy during 2021. Parsing the rise in government bond yields—which reflects a combination of better growth prospects, risks of inflation, and concerns about rising debt levels—encapsulates the challenges that policymakers face as they try to decipher and manage market expectations. Any additional stimulus measures should ideally aim to simultaneously boost aggregate demand and improve long-term productivity.

China’s growth momentum has stayed strong and balanced, with the government’s attention turning to medium-term structural issues and containment of financial system risks. The recent National People’s Congress meeting ended with a renewed focus on rebalancing demand toward household consumption and shifting growth sources toward high-end manufacturing, the services sector, and small and medium enterprises. The government seems to be leaning toward normalization of macroeconomic policies, with a lower fiscal deficit and some tightening of monetary policy anticipated later in the year. This is being backed up by prudential regulatory measures to manage frothiness in the real estate sector. Trade tensions with the U.S. now appear likely to persist under the Biden administration, but this no longer seems a major factor influencing private sector sentiment or growth in either country.

European economies, both in the core and periphery of the eurozone, are struggling as they cope with another wave of COVID-19 infections, floundering vaccination programs, and a lack of policy direction. While industrial production, particularly in Germany, has held up well, much of the eurozone might return to pre-COVID-19 GDP levels only by late 2022. The U.K., which in 2020 faced a double whammy from Brexit and COVID-19, has made good progress on vaccinating its population and improved its growth prospects. Japan’s recovery appears fragile. Despite extensive stimulus measures, weak consumer confidence is restraining consumption while export growth has been subdued.

In India, both the manufacturing and services sectors are contributing to a strong rebound.

However, a resurgence of the virus and limited policy space due to high public debt levels and rising inflation could erode some momentum. The rebound in oil prices has buoyed the prospects of countries such as Nigeria, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. Meanwhile, Brazil’s economy is tottering as the virus spreads unchecked and ineffectual political leadership hampers a concerted response. Turkey faces similar concerns, although it was one of the few economies to register positive growth in 2020. In short, even among emerging markets, there are multiple tracks to the recovery.

Following a marked decline during 2020, the U.S. dollar has firmed up in 2021. In tandem with the upward shift in U.S. bond yields, this portends ill for many emerging market and other developing economies, particularly those with heavy foreign currency debt exposure. Financial market pressures could build up if divergent growth patterns, with more vulnerable economies registering weaker growth, persist through 2021.

Policymakers around the world face an important pivot point. One decision many countries are grappling with is whether to open up their economies despite the continued spread of the virus. Another is whether to infuse additional macroeconomic stimulus, risking an unfavorable tradeoff between short-term benefits and longer-term vulnerabilities. Uncertainties are rife and the stakes are high. Indecisive policies are affecting consumer and business confidence in the weaker economies, adding to economic strains.

The recipe for a strong and durable recovery remains the same as it has over the past year—resolute measures to control the virus coupled with balanced monetary and fiscal stimulus, with an emphasis on policies that support demand as well as improve productivity. In economies that are doing well, it is far too early to ease up in either dimension while in others policymakers will need to redouble their efforts.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).