The Federal Reserve has been drawing derision lately for its “forward guidance” — its vow to keep short-term interest rates very low until the job market gets a lot better.

But this criticism comes when forward guidance finally seems to be working. Fed policymakers (according to their published forecasts) and financial markets (according to trading in futures markets) both expect the Fed to keep short-term rates near zero well into 2015.

Some background: The Fed cut short-term interest rates to zero in late 2008. That wasn’t enough to resuscitate the U.S. economy so it found other tools, aiming to push down the long-term interest rates that homebuyers and businesses pay and thereby give the economy a boost.

One tool was to buy trillions of dollars of Treasury bonds and mortgages (“quantitative easing”). That amounted to pushing down longer-term rates with brute force. The other was to pledge to keep short-term interest rates low for a long time. That was an attempt at persuasion; the bond market sets long-term rates in part based on its view of future short-term rates.

Let’s clear up a bit of confusion, much of it generated by the Fed’s move to use an explicit unemployment rate threshold of 6.5% in its statements beginning in December 2012 (when unemployment was at 7.8%). It said then that it wouldn’t raise short-term interest rates until joblessness fell at least to that level. Unemployment has now fallen to 6.6%.

The Fed hasn’t said it would raise short-term rates when unemployment hits 6.5%. In fact, it said otherwise. In its December statement—in language new Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen is likely to reiterate in her testimony Tuesday and Thursday—the Fed’s policymaking Federal Open Market Committee said it expects short-term rates to be very low “well past the time that the unemployment rate declines below 6-1/2 percent,” especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee’s 2 % longer-run goal.

How long is “well past the time?” Somewhere between six months and a year. At his December press conference, then-Chairman Ben Bernanke noted that published forecasts of Fed policymakers show most expected unemployment to hit 6.5% by the end of 2014, but didn’t expect to short-term rates to rise until the end of 2015. He described 6.5% unemployment as “the point at which we would begin to look at a more broad set of labor market indicators… such as hiring, quits, vacancies, long-term employment, wages, etc.”

(That may sound complicated, but it’s a whole heck of a lot simpler than the Bank of England’s forward guidance—which the Bank of England is expected to tweak Wednesday.)

The ultimate test of the Fed’s monetary policy is how close it comes to meeting its mandate of price stability and maximum sustainable employment. Right now, it’s falling short on both.

In the meantime, one way to see if forward guidance is working is to look at what financial markets expect the Fed to do; after all, this tool only works if markets believe the Fed.

For a time, markets were skeptical. As John Williams, president of the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank, recalled recently: From 2009 to mid-2011, markets expected the Fed would move swiftly to raise rates “despite the efforts of many on the FOMC to communicate the severity of the downturn and the result need for highly accommodative monetary policy for quite some time.”

Last spring, Mr. Bernanke began talking about reducing the scale of the Fed’s bond-buying. The markets saw that as a move towards tightening credit and raising rates, although that wasn’t Mr. Bernanke’s intent. So he and others at the Fed spent a few months reinforcing its message that it wasn’t rushing to raise rates.

This time, the markets got it.

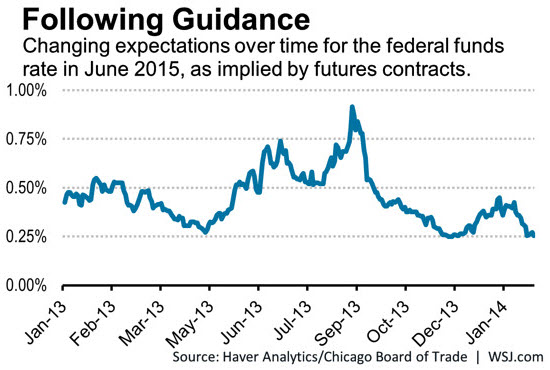

How do we know? Look at the chart with this column, which Jon Hilsenrath has posted previously. It tracks the trading in the federal funds futures market where people put money on their bets on what the Fed will do when. The fed funds rate (the Fed’s key short-term rate) is now about 0.06%, as close to zero as practical. The chart shows what markets anticipated that rate to be in June 2015 at various points in time.

When the Fed began talking about tapering last spring, markets began betting that the Fed would be raising rates well before June 2015. By August 2013, markets were expecting Fed funds to be approaching 1.0% by June 2015—not what most Fed officials anticipated.

Today, the markets expect the fed funds to hit 0.2% by June 2015. That is very close to what Fed policymakers’ published forecasts show. And that is happening at the very moment that the Fed is scaling back its bond buying.

“In some very broad sense, [forward guidance] has been effective,” says Lewis Alexander, chief U.S. economist at Nomura. “I think that the FOMC has been able to send the basic message that they will maintain very accommodative policy for a long time and that has supported the recovery in important ways. That’s really the most important way to judge the success of the effort.”

There are a lot of lingering questions about exactly how the Fed will read the job market—especially if the unemployment rate falls not because there’s a lot of hiring, but because a lot of people stop looking for work. It’s hard to know what the Fed will do if the outlook for the economy worsens or improves significantly—or if inflation materializes before the job market returns to health.

But, for now, forward guidance is working

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edAhead of Janet Yellen’s Testimony, Fed’s Forward Guidance Is Working

February 11, 2014