Introduction

Elementary and secondary schools prepare young people to enroll in higher education, succeed in the labor market, and engage as active citizens. Quality education is also an important driver of innovation and economic growth, and improving schools for children growing up in low-income families or disadvantaged communities is a long-standing policy project. A hotly debated element of this effort in recent decades is the question of how much additional funding alone—without changes to the incentives, institutions, and regulations governing how schools operate—could improve student outcomes.

Starting with the Coleman Report in 1966, early studies came to a surprising conclusion: Spending and educational outcomes were weakly related (Coleman et al. 1966; Hanushek 1997; Jencks 1972). The academic literature on the relationship between funding and outcomes came to be known by the shorthand “Does money matter?” That framing of the issues is, at best, imprecise.1 Spending proponents and skeptics alike agree that schools are important and need money to function; in that sense money “matters.” More recently, researchers have come to a consensus more in line with the common intuition that, on average, additional funding improves educational outcomes (Handel and Hanushek 2023; Jackson and Mackevicius 2024). But that leaves open the questions of how much and under what conditions money affects outcomes and whether other approaches to improving schools might work better. Policymakers, advocates, and other observers might ask whether underfunding is the primary barrier to school improvement.

On the one hand, it is deeply intuitive that additional funding could solve the kinds of problems Jonathan Kozal chronicled in his influential best-seller, “Savage Inequalities”—crumbling infrastructure, lack of critical supplies, understaffing, and overcrowding (Kozol 2012). On the other hand, although modern studies show positive effects of school spending, the effects are arguably small on average and sometimes negligible, and substantial increases in per-pupil spending over time have often been met with stagnant academic achievement. This raises questions about the significance of other barriers to improving schools, such as rules related to staffing and teacher pay, standards and curriculum, or incentives for schools and students. It may be that addressing those barriers is critical to improving school quality and productivity.

To improve schools, should policymakers and advocates focus primarily on increasing funding or other reforms? Of course, these options are not mutually exclusive, but policy and research attention are limited. This question is especially important for state policymakers since that is the most important level of government when it comes to school funding.

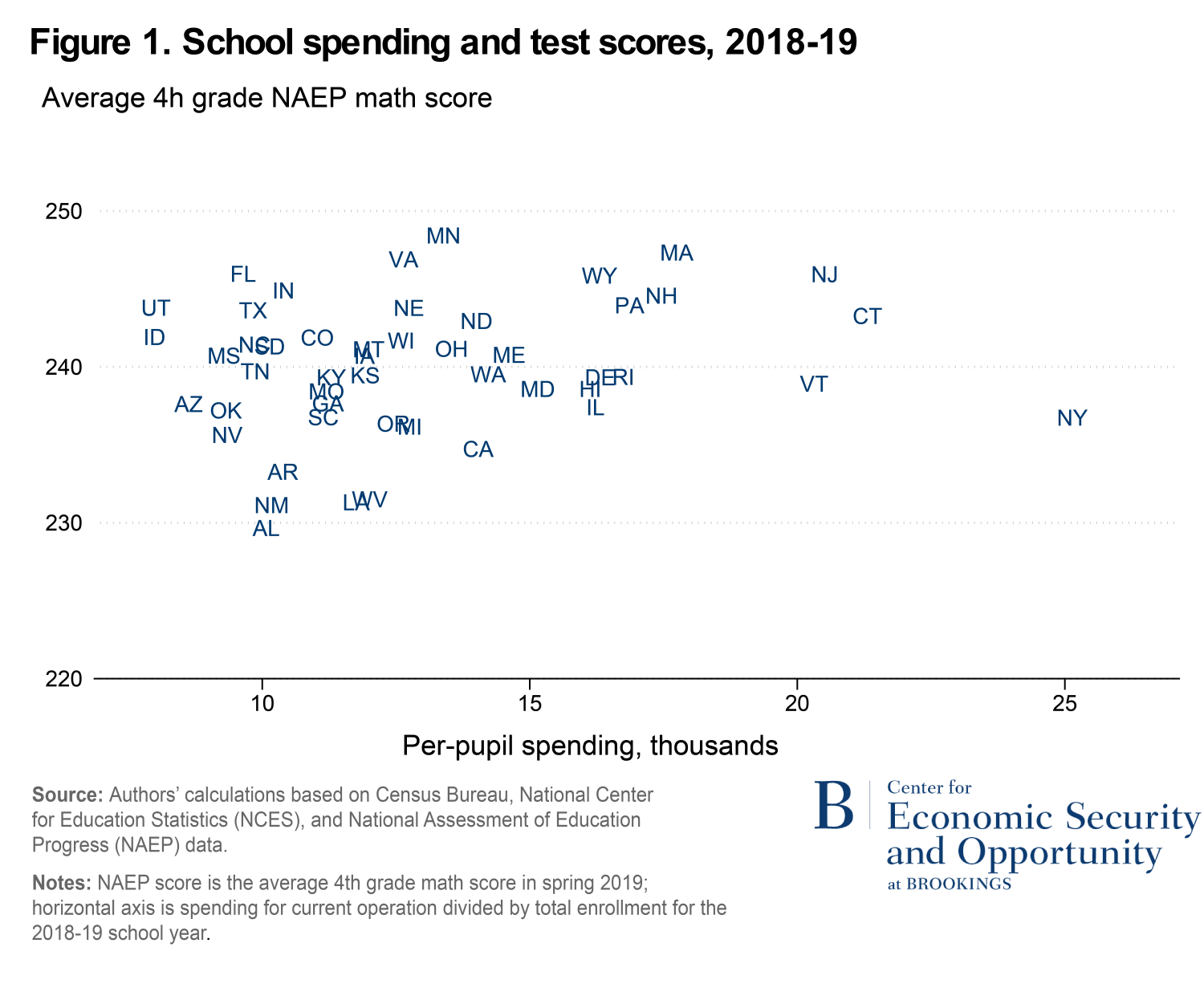

Figure 1 shows that differences in average per-pupil spending across states are substantial but not strongly related to average test scores (in this case, the average fourth grade NAEP math score for 2018-19, the last school year before the COVID-19 pandemic). What should policymakers and other observers make of this fact? To shed light on this question, in this report we analyze cross-state differences in spending and outcomes in-depth—and show how this has changed over time.

Interpreting cross-sectional input–output relationships is difficult. Both student needs and prices for the key inputs schools must buy vary across states. These variables could be correlated with both spending and outcomes, meaning the relationship cannot be interpreted causally. This is exactly the reason recent research has focused on finding ways to address this “omitted-variables” problem to estimate causal effects of spending on educational outcomes (Jackson and Mackevicius 2024).2

Still, as we show below, differences in per-pupil spending across states are large and persistent. Schools in the highest-spending states spend two times as much—or more—compared to those in the lowest-spending states. It would have cost almost $600 billion in 2018-19 to increase per-pupil spending in all states to the average in the highest-spending state (New York), which would almost double total current expenditure and is an order of magnitude larger than the existing federal aid for elementary and secondary education (around $60 billion in 2018-19). New York is particularly high spending, but even increasing spending to the level of the next-highest-spending state (New Jersey) would have cost about $360 billion. So, while other factors may influence educational outcomes, differences in funding across states are large enough that—if money is a key driver of school quality—we would expect to see differences in outcomes across states; and we believe examining that relationship systematically has merit.

Focusing on the 2018-19 school year, the last before the pandemic disruption, we find a weak relationship between per-pupil school spending and educational outcomes as measured by test scores and high school dropout rates. As a benchmark, we compare the magnitude of the spending–outcome slope with the average causal effect of spending on test scores and educational attainment from a recent meta-analysis by Jackson and Mackevicius (2024) (henceforth, JM). Without controlling for any other characteristics of states, the spending–outcome slope is about half of the average effect in JM for test scores and one-quarter or less as large for high school dropout/graduation. We show that this finding largely does not depend on the choice of test scores, grade, subject, whether we weight by enrollment or exclude New York (a high-spending, low-outcome outlier), or whether we adjust spending to account for differences in input costs. The small positive slope appears to be driven by differences in socioeconomic status across states: Controlling for the state poverty rate and/or per-capita income generally reduces the slope close to zero.

The relationship between per-pupil spending and outcomes for economically disadvantaged students is of particular interest for several reasons. First, policymakers are especially interested in the outcomes of disadvantaged students. Second, we show that economically disadvantaged students living in higher-income states are exposed to higher school spending compared to their counterparts in lower-income states. That is, economically disadvantaged students in richer, higher-spending states experience higher spending even though they themselves are not high-income. Third, families might increase out-of-school investments when spending is low, obscuring the relationship between spending and outcomes, but the families of economically disadvantaged students are less able to compensate in this way. Finally, the JM meta-analysis suggests that the causal effects of spending are larger for disadvantaged students. We do not, however, find a steeper spending–outcome slope for economically disadvantaged students. In fact, the relationship between school spending and test scores or high school graduation is, if anything, flatter for more disadvantaged students.

Analyzing the spending–outcome relationship since the early 2000s suggests that the slope may have been steeper in the past and approached the average causal effect in JM, but again, controlling for per-capita income and/or poverty reduces that relationship substantially. Overall, the general conclusion one might draw from looking at Figure 1 holds up: Average spending varies across states, as do average test scores, but the two are not very correlated. The picture for high school graduation is similar.

We also examine how spending choices differ in lower- and higher-spending states. Overall, spending appears to be more-or-less scaled up in higher-spending states. That is, the allocation of spending across functional categories is similar across states, and higher-spending states employ more staff across all categories and pay teachers more. The higher teacher salaries in higher-spending states are partially due to higher wages for college educated workers generally, but higher-spending states also pay more relative to prevailing wages.

We conclude by exploring some potential explanations for the unexpectedly small relationship between school spending and educational outcomes that we document. We are particularly interested in distinguishing between explanations that imply that schools in higher-spending states do not use their funding as effectively and explanations related to differences in student needs or input prices, which would not necessarily imply productivity differences across states. Overall, we think the findings suggest that improving schools is not, in general, a mere matter of money (although more money would probably help in some circumstances). This means that policymakers and researchers should devote as much attention to understanding and improving productivity in education as they do to the level and distribution of funding. The weakening relationship between spending and outcomes over time also warrants more attention.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are grateful to Gabriel De Luca Vinocur, Elizabeth Link, and Sophie Pinkston for exceptional research assistance.

-

Footnotes

- References to this phrase predate the publication of a Brookings Institution volume edited by Gary Burtless titled “Does Money Matter? The Effectiveness of School Resources on Student Achievement and Adult Success” in 1996, but that influential volume may have increased the use of this unfortunate terminology (Burtless 1996).

- Another strand of analysis attempts to estimate the cost of providing an “equitable” or “adequate” education, or the cost of meeting academic standards, for schools serving populations with varying educational needs, often as part of school finance litigation (Mattoon 2004). For example, Baker et al. (2018) use a “cost model” approach to estimate the cost of reaching average student achievement based on student and other characteristics of school districts; they find a positive state-level relationship between “funding gaps” (based on the model) and “outcome gaps” (based on test scores). Determining the minimum cost of meeting educational targets is a challenging task, and the cost modeling approach has both conceptual and practical limitations (Costrell et al. 2008). We take a simpler approach, examining how actual spending relates to outcomes for different groups.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).