Tere, a young woman living in an urban neighborhood in western Mexico, dreams of a better future. She completed her secondary education, surpassing her mother and partner’s education, but without child support or affordable childcare, she cannot work or study. Her aspirations are overshadowed by poverty, partner violence, and unpaid care and domestic work. A public food assistance program provides her a basic income, easing the strain of her partner’s irregular income. Yet, despite programs supporting women’s entrepreneurship and job training, Tere remains trapped in a cycle of dependency.

Tere’s story reflects the reality of more than 15 million women in Mexico1 who face intersecting challenges and remain trapped in systemic inequalities, unable to leverage the tools and promise that formal education has offered for better economic prospects. Over the past two decades, Mexico, a middle-income country, has developed a robust legal and institutional framework for gender equality. Today, gender parity in basic education has been achieved, and women’s enrollment in graduate and postgraduate programs now surpasses men’s. However, the 31% gap between men and women in access to paid work highlights persistent barriers to women’s economic autonomy.

Women’s economic autonomy: A multidimensional construct

Women’s economic autonomy (WEA), defined as a woman’s ability to generate income and have control over financial resources, based on equal access to paid work, is a multidimensional construct that requires a comprehensive policy approach from the State. A mapping of public programs in Mexico revealed 89 public programs at the federal, state, and municipal levels that address at least one aspect of economic autonomy, yet few of these provide a holistic approach that combines multiple components to address intersectional inequalities.

Existing single-component programs fail to address the intersecting barriers that marginalized women like Tere face, leaving many behind. Research highlights the need for tailored, multifaceted interventions to effectively break cycles of poverty and inequality. Additionally, territorial and administrative fragmentation in programs exacerbates challenges for marginalized women, with WEA programs being delivered by multiple agencies across government levels with limited coordination, imposing high transaction costs. Women like Tere must navigate bureaucratic hurdles, transportation costs, and time investments, further limiting their access to economic autonomy opportunities.

The current WEA policy landscape in Mexico reinforces entrenched economic and social inequalities, trapping marginalized women in cycles of poverty, gender-based violence, and unpaid care and domestic work. Addressing these policy limitations is essential to creating inclusive, integrated, and transformative pathways to economic autonomy for all women in Mexico.

Shifting mindsets for transformative policy change

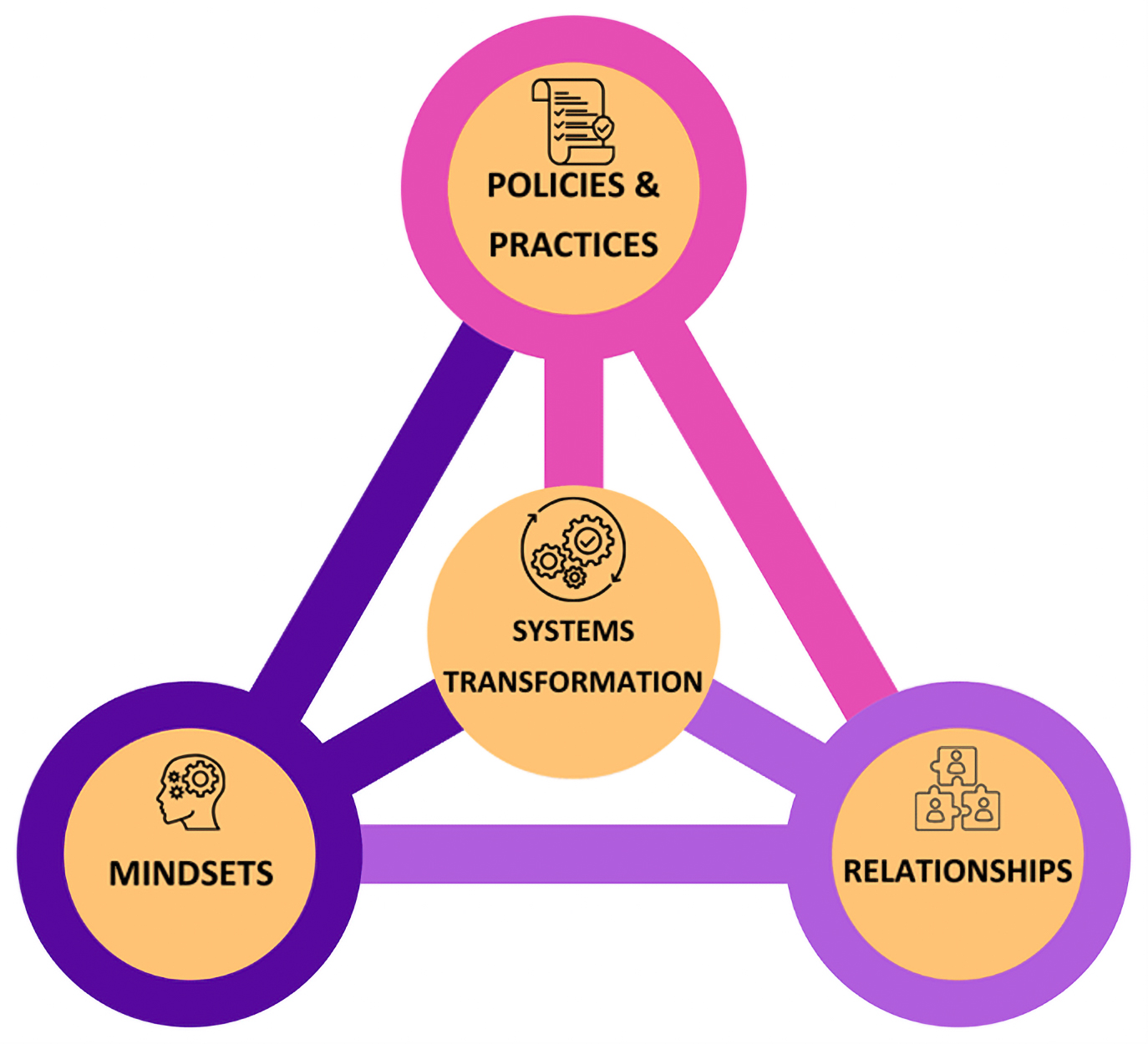

To address these challenges and advance marginalized women’s economic autonomy in Mexico, it is crucial to understand and shift the mental models that will allow systems transformation to tackle inequality, rather than perpetuate it. Particularly uncovering policymakers’ mindsets, their habits of thought, deeply held beliefs, and assumptions about gender equality and WEA and how that influences their relationships, policy responses and practices (Figure 1).

Over the past four months as an Echidna Global Scholar at the Center for Universal Education, I have researched the mindsets of policymakers in economic, education, social, and gender policy in the state of Jalisco, Mexico. Through in-depth interviews with over 20 policymakers, I examined the policymaking process—and the mental models that inform it—to identify ways to better align WEA programs with the needs of marginalized women. My research focused in particular on second-chance education programs, which hold potential to improve marginalized women’s economic autonomy by providing holistic training and mentoring services, along with support networks.

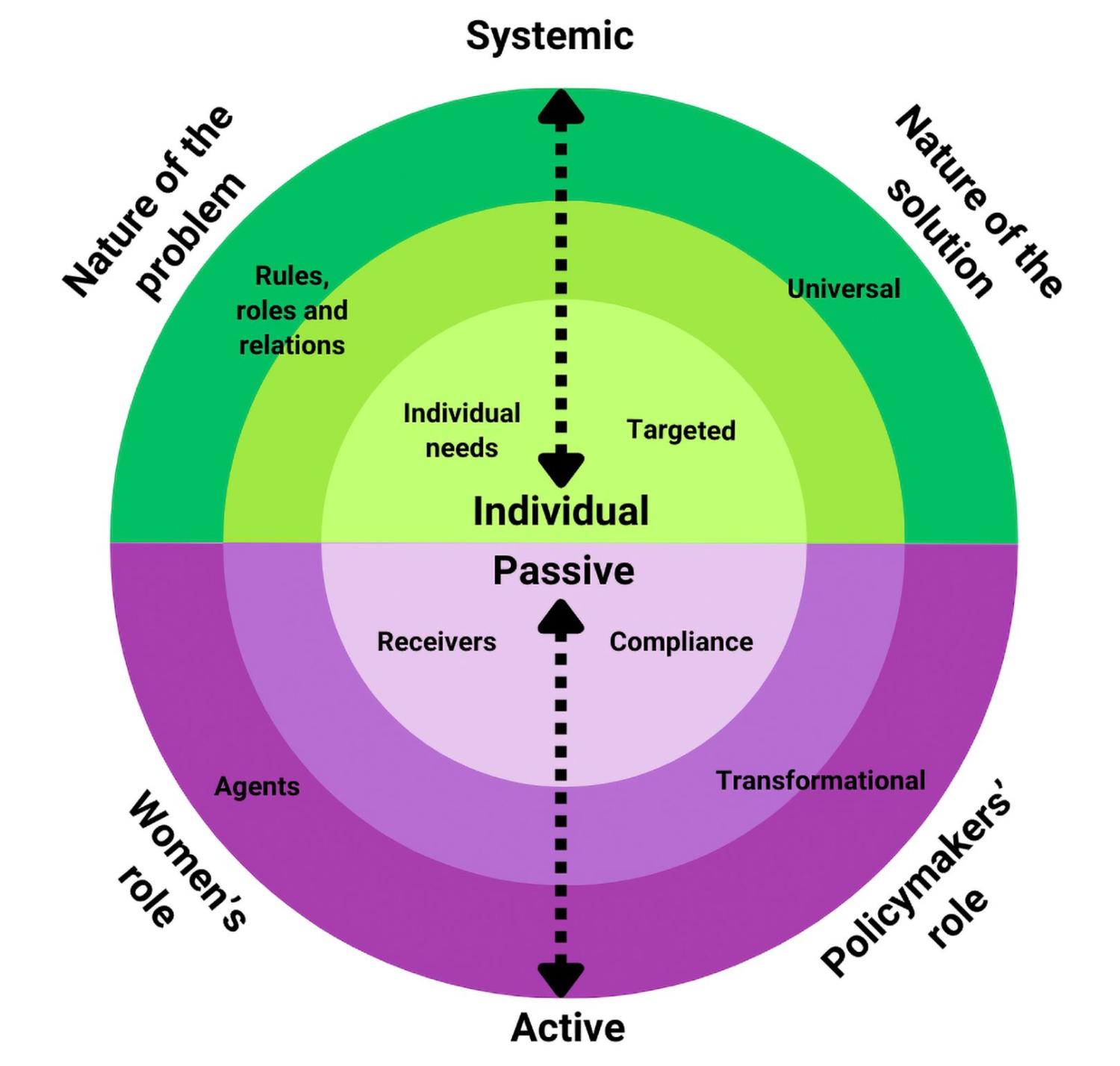

Figure 2. Policymakers’ mindsets: A map to navigate complex decision-making processes related to WEA

The research showed how policymakers’ mental models relate to WEA policies in four different ways: how they understand the nature of the problem and the solution, and the way they frame women’s role and their own in relation to policy. These mindsets are represented as a Mindset Map (Figure 2) to illustrate the complexity of decision making and the multiple narratives that shape policymakers’ approaches to WEA. The Mindset Map can be used as a tool for navigating the continuum of beliefs and assumptions that policymakers hold with respect to WEA and gender equality in general.

Policymaker mindsets are crucial in shaping WEA policies and the experiences of marginalized women accessing these programs. For example, in relation to the mental model around women’s role in WEA, if a policymaker views women as “receivers” their preferred policy response may focus on providing cash transfers or food aid, addressing only women’s immediate needs but failing to promote economic autonomy. Alternatively, viewing women as “agents” might lead to training programs that tap into their potential, such as building skills. When policymakers position themselves at the extremes of the continuum, they might neglect women like Tere, who face childcare responsibilities with no access to any type of support, and experience gender-based violence, and poverty. To be more effective, WEA policies must recognize the need to both strengthen skills and confront the structural and cultural barriers impeding their progress.

Mindsets can change

The research highlighted that policymakers’ life experiences shape their mental models, which can evolve over time. Some policymakers interviewed shared how personal experiences such as motherhood, social service, travel, training, or experiencing violence and discrimination changed their perspectives. Many also acknowledged that interacting with women facing gender inequalities deeply impacted their understanding. However, most policymakers reported having limited contact with women living in marginalization, such as Tere. This disconnect affects how they perceive the challenges women face, particularly in the context of WEA programs, and can limit the development of more comprehensive policies suitable to address the intersectional barriers women like Tere face.

A key step in expanding the economic autonomy of marginalized women in Mexico is strengthening local ecosystems that address poverty, gender-based violence, and unpaid care work. This requires a collective commitment, particularly from policymakers in the gender, education, and social development sectors, to rethink WEA policy with a shared vision centered on marginalized women. Two key actions are needed: first, implementing holistic, multisectoral programs that align social development, education, and gender programs at the local level, leveraging community infrastructure; and second, strengthening civic participation policies to amplify the voices of women like Tere. Direct engagement with women, including those who have not participated in or have dropped out of WEA, will provide valuable insights to improve policy responses and interventions. By prioritizing marginalized women, we can increase their autonomy and create positive ripple effects for their families and communities, promoting shared prosperity across Mexico.

-

Footnotes

- Author’s estimation based on public data from CONEVAL (2024). This figure represents the sum of women experiencing poverty, care inequality, and violence. Due to gaps in available data, this estimate does not account for economically inactive women in poverty without children but with other caregiving or domestic responsibilities (e.g., extended family or community care), self-employed women in the informal economy, or women facing other intersecting barriers such as health challenges, ethnic or racial discrimination, or disabilities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A path to shared prosperity in Mexico

Making policies for economic autonomy work for all women

December 16, 2024