Discussions on AI are occurring at all levels of government including federal, state, and local as each entity tries to understand, leverage, and protect from AI. In August 2025, we identified the states leading and lagging on AI governance along with the salience of different issues associated with the technology. In this analysis, we unpack what factors lead to the introduction of bills at the state level and, more importantly, what factors might constrain these efforts. Some states are racing ahead with detailed frameworks, while others have introduced just a few bills. This patchwork emergence of AI legislation matters because it shapes how citizens are protected from abuse, how information ecosystems respond to AI-generated deepfakes and AI-driven automated decision-making, and whether governments establish institutions capable of governing AI over the long run. It also provides a backdrop for the current efforts by the White House to curb state-led legislation.

In this study, we examine all AI-related bills introduced from January 2023 through October 2025 across all states to understand which are acting, which are not, and why. We classify bills into three overarching themes and then identify the structural and political conditions most closely associated with legislative activity and inaction. The result is a simple but powerful two-barrier model that can guide realistic strategies for responsible AI governance in different state contexts.

Methodology

Our analysis draws on AI-related legislation tracked by Brookings for the 2025 state legislative session. We attempted to capture all AI-related bills introduced across the 50 states and their status at the end of session: passed, rejected, or dead. This totaled 385 bills, with at least one bill introduced in all 50 U.S. states. We grouped approximately 20 substantive categories of bills into three overarching themes: protection of the individual, transparency and trust in information ecosystems, and responsible systemic governance. This aggregation provides a parsimonious structure that captures variation in policy aims while remaining faithful to the underlying bill descriptions.

We then linked legislative activity in each state to a small set of structural and political conditions. Population age structure was measured using 2024 state data from the United States Census Bureau, with higher scores (more than 55) indicating older populations. Per capita income and poverty were taken from the 2024 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, where higher poverty-defeating scores indicate greater success in lifting residents above the poverty line. Governor party is coded from official state sources, with Democratic governors coded high and Republican governors coded low. Party base is constructed from Inside Elections data on state-level voting patterns, with higher values indicating a Democrat-leaning electorate and lower indicating Republican.

We conducted qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to examine how conditions combine to produce high or low activity in each state. Using the calibrated data, we constructed configurations for each outcome and assessed them using degrees of coverage at two levels. Configuration coverage assesses the empirical relevance of configurations by indicating how much of the outcome they explain, while solution coverage reflects the explanatory power of all identified configurations combined. We summarize QCA solutions in a heat map that highlights necessary and absent conditions and their solution coverage and then follow this with Venn diagrams that highlight intersection of configurations and their individual coverages.

Our findings

In our analysis of the four outcomes, we identify positive (high AI bill production) and negative (low AI bill production) outcomes. We use a heat map to identify the core conditions to capture the solutions, explaining each configuration and giving state examples. Orange indicates a necessary presence, blue indicates a necessary absence, and gray denotes conditions for which presence or absence does not impact the outcome. Solution coverage is captured at the bottom of the table and is classified as low (L, <0.25), medium (M, 0.25<0.50), high (H, 0.50<0.75), or very high (V, >0.75). Individual conditions are read horizontally in rows, while configurations are read vertically in columns. For example, the first row identifies that an aging population is a necessary presence in the “All Bills Low” configurations 2 and 3 and the “Governance Low” configurations 2, 3, and 4, and a necessary absence for the “All Bills High” configuration 1. Conversely, the first column identifies that for “All Bills High” configuration 1 (with high coverage between 0.50 and 0.75), an aging population is a necessary absence while a Democrat-leaning base is a necessary presence.

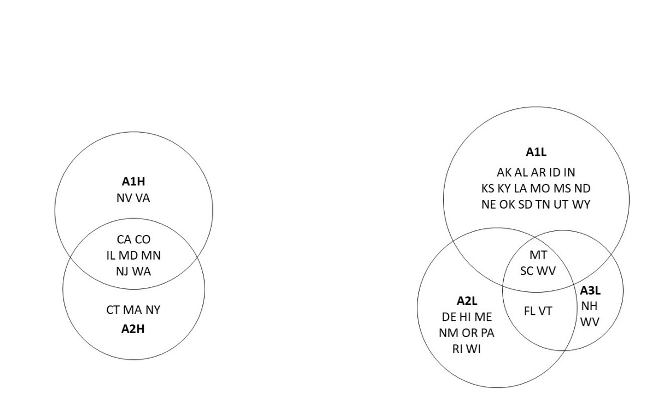

In describing these parsimonious configurations, we provide Venn diagrams that show the relationships between groups of states. In these diagrams, the size of each circle or ellipse is representative of degree of coverage of the configuration within the overall solution, so a larger circle indicates greater coverage and explanatory power in the model.

We first examined high performance for “All Bills,” defined as the introduction of any AI legislation by states. Two high-performing configurations emerged. The first (A1H) consists of Democrat-leaning states with younger populations. The second (A2H) includes high–per capita income states led by Democratic governors. Several states fall into both configurations—New York, California, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, and Washington—all of which combine relatively young populations, strong fiscal capacity, and Democratic political control. Nevada and Virginia align only with the first configuration (A1H), while Massachusetts and Connecticut align only with the second (A2H). Together, these patterns suggest that Democratic leadership and partisan alignment create ideological and institutional momentum for AI policymaking, an effect that is reinforced by younger, more technologically literate electorates and the fiscal resources needed to design and administer technology regulation.

We compare these findings with low performance, defined as the absence of AI legislation at the state level. Three distinct but complementary paths account for this lack of legislative activity, reflecting the inverse of the conditions associated with high performance. The first configuration (A1L) includes states with a Republican-leaning electorate. The second (A2L) consists of states with older populations and lower per capita income. The third (A3L) includes states led by Republican governors and characterized by older populations.

The first configuration is composed largely of conservative states stretching from Alaska to Florida, across the heartland, and throughout the South. The second includes a mix of Democratic- and Republican-leaning states, ranging from Hawaii to Maine, as well as battleground states such as Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Some overlap exists across configurations: Florida and Vermont appear in the latter two, while South Carolina, Montana, and West Virginia are represented in all three.

Taken together, these patterns suggest that Republican governors and partisan alignment contribute to ideological and institutional inertia, while older population bases further reinforce legislative inaction. In these contexts, states tend to prioritize conservative fiscal management and established policy areas over emerging forms of technological regulation.

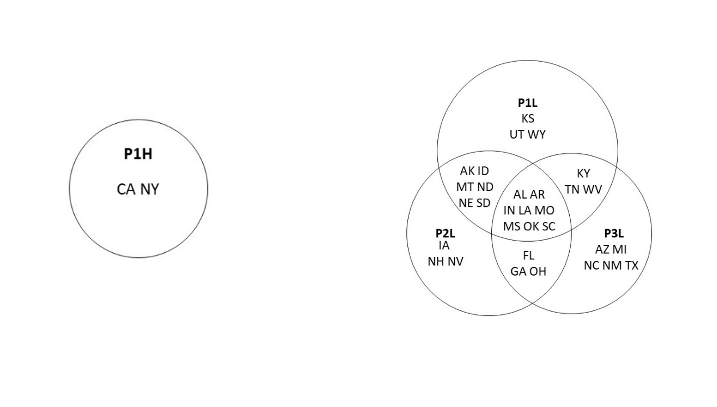

There was a lone high protection solution (P1H) in Democrat-leaning states with high income and high poverty rates (high income inequality). California and New York epitomize these cases.

We next examined low protection of the individual in AI legislation, for which three distinct paths emerged. The first two were political in nature: one (P1L) centered on a Republican party base, and the other (P2L) on Republican gubernatorial leadership. The third configuration (P3L) was economic, combining lower income levels with higher poverty rates. These configurations showed substantial overlap and together encompassed nearly the entire South, from Arizona to West Virginia and Florida, with Virginia as the lone exception. They also covered most of the West, excluding the Pacific Coast states, and extended into the western Midwest, stopping at Minnesota and Illinois. Given the predominance of political factors across these configurations, our findings suggest that low levels of “protection of the individual” in AI bills are driven primarily by political will, with fiscal capacity acting as a secondary constraint.

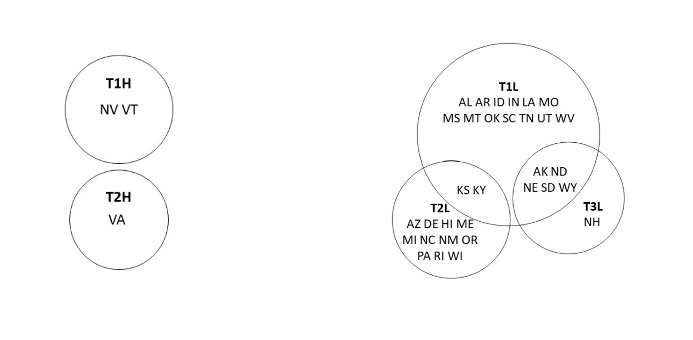

There were two paths to high-transparency bills, but both had low coverage, indicating that they represent narrow pathways. Both configurations involve Democrat-leaning states with Republican governors, though one (T1H) is characterized by lower per capita income and the other (T2H) by higher poverty, reflecting greater income inequality. The former includes Vermont and Nevada, while the latter includes Virginia.

Low transparency bills had three configurations. The first (T1L) was identical to protection bills—a Republican-dominated party base. This configuration was primarily in areas bounded by North Dakota, Idaho, Utah, and Alabama—the heartland and South—but excluding populous states such as Texas and Florida. The second (T2L) was a low per capita income state with a Democratic governor, including states such as Rhode Island, Hawaii, and New Mexico. The third (T3L) was a high-income/low-poverty state with a Republican governor, including states that are on the surface as diverse as New Hampshire and Wyoming. Transparency bills—such as laws addressing deepfakes, chatbots, or content provenance—require administrative sophistication and technical engagement, both of which are scarce in poorer states and ideologically deprioritized in conservative ones.

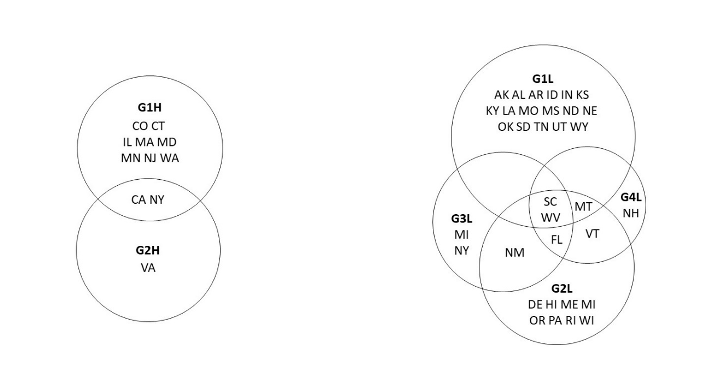

There were two paths to high rates of governance bills, both of which showed moderate coverage. The two paths were high-income states, signifying a have-state with resources to implement and manage AI regulations, but one (G1H) included high poverty, while the other included a Democratic governor. The former included states such as Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Washington, while the latter included California and Virginia.

Finally, low introduction of responsible governance legislation appeared across four configurations with either high or moderate coverage. The first (G1L) consists of deep-red Republican states, where ideological opposition to government involvement in AI regulation limits legislative activity. This configuration spans a conservative triangle from Idaho in the Northwest to West Virginia in the East and Florida in the Deep South. The remaining three configurations share older populations as a common condition and are differentiated by additional factors: low per capita income (G2L), high poverty (G3L), and Republican governors (G4L). Together, these reflect states that are older, poorer, and more conservative.

Emerging trends

Across the four high-performing models, a consistent pattern emerges: States legislate when either structural capacity or ideological motivation is strong enough to trigger regulatory action. In this sense, AI legislation appears conditional, requiring the right combination of political will and either demographic readiness or fiscal resources. High activity in All Bills and Governance occurs primarily in wealthier states with Democratic-leaning party bases or governors, reflecting both the fiscal capacity and administrative depth needed to design and manage AI oversight. A younger population also appears to facilitate overall bill activity, while an aging population functions more as a brake. Protection legislation emerges only in high-income states with high income inequality and Democratic leadership, where political motivation heightens attention to individual harms. By contrast, Transparency shows only narrow pathways to high activity, each confined to small groups of Democrat-leaning states with mixed economic profiles, suggesting that this domain requires both political will and at least minimal capacity. The narrowness of Transparency further indicates that these bills may depend more on policy entrepreneurship than do other domains.

The four low-performing models show the mirror image of these patterns. Low activity in All Bills and Protection is driven largely by conservative political alignment, where a Republican electorate or governor consistently suppresses the introduction of AI legislation. This reinforces that political preferences can outweigh administrative capacity in determining whether states engage with AI regulation at all. Low Transparency emerges from three different contexts: conservative states; poorer Democratic-governor states with limited administrative capacity; and high-income states with Republican governors who deprioritize information-integrity regulation. Low Governance likewise reflects either deep-red ideological opposition or the material limits associated with older, poorer populations. These configurations reveal that inaction is produced either by states that choose not to act (ideological resistance) or by states that cannot act (capacity constraints).

Conclusion

Examining the symmetry between high and low configurations reveals a striking regularity: The conditions that drive legislative action are nearly the inverse of those that produce inaction. Democrat-leaning, wealthier, and younger states appear in nearly all high-activity pathways, while Republican-leaning, poorer, and older states account for most low-activity pathways.

This pattern also holds within individual policy domains. Protection bills emerge when high income coincides with Democratic alignment and recede when low income overlaps with Republican control. Transparency bills appear only in contexts where political contestation favors intervention and disappear when contestation suppresses it, making transparency the most context-dependent domain, with high activity confined to narrow and highly specific pathways.

Governance bills increase with greater fiscal capacity and decline in low-capacity environments, but income alone does not guarantee action. Instead, fiscal capacity enables governance, while political will determines whether that capacity is mobilized. This symmetry reinforces the model’s central insight: AI legislation depends on both ability (capacity) and appetite (ideology), and the absence of either reliably constrains policymaking.

Taken together, these findings point to two distinct barriers to AI governance. First, a material barrier—driven by limited fiscal and institutional capacity—prevents some states from acting even when risks are recognized. Second, an ideological barrier, rooted in regulatory skepticism and market-oriented political preferences, constrains action even where capacity is strong. These barriers reproduce a familiar divide in U.S. policy innovation, mirroring long-standing patterns in areas such as environmental regulation, health technology, and digital privacy.

In the context of AI legislation, policy leadership is therefore likely to cluster in wealthier Democratic states, while diffusion across other states remains uneven due to variation in ideology and capacity. For policymakers, the implication is clear: AI governance must be tailored to states’ structural and political realities, potentially offering an alternative to outright bans on state-level legislation. Where capacity is limited, investment and institutional support are most critical; where ideological barriers dominate, reframing, coalition-building, and targeted policy design become essential.

One significant development affecting states’ ability to pass AI legislation is President Trump’s executive order, signed Dec. 11, 2025. The order seeks to preempt state-level AI laws, promote U.S. dominance in artificial intelligence, and require truthful AI outputs. It also carries enforcement mechanisms: The U.S. attorney general is directed to challenge state laws deemed to impede AI leadership, and federal infrastructure funds may be withheld from states that fail to comply. In effect, the order consolidates AI authority at the federal level and constrains state regulations viewed as burdensome, reflecting the same ideological posture observed in many Republican-led states. Given the order’s recent issuance and uncertainty surrounding its implementation, its ultimate impact remains difficult to assess.

We expect a rigorous debate to continue, particularly after the Senate defeated a bill in July by a 99-1 vote that would have imposed a 10-year moratorium on state AI regulation. Senators and governors, both Republican and Democratic, appear to have sharply different views on the role of states in crafting AI laws, so the issue remains unresolved.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).