Below is the seventh chapter from “A Better Path Forward for Criminal Justice,” a report by the Brookings-AEI Working Group on Criminal Justice Reform. You can access other chapters from the report here.

Over 640,000 people return to our communities from prison each year. However, due to the lack of institutional support, statutorily imposed legal barriers, stigmas, and low wages, most prison sentences are for life—especially for residents of Black and Brown communities. More than half of the formerly incarcerated are unable to find stable employment within their first year of return and three-fourths of them are rearrested within three years of release.12

Research has demonstrated that health, housing, skill development, mentorship, social networks, and the collaborative efforts of public and private organizations collectively improve the reentry experience.3

More than half of the formerly incarcerated are unable to find stable employment within their first year of return and three-fourths of them are rearrested within three years of release.

Level Setting

Prisoner reentry should be understood as a critical piece of any racial justice agenda. Imprisonment rates are five to eight times higher for Black Americans than any other racial/ethnic group, and historically disenfranchised neighborhoods receive the bulk of returning citizens.456 For example, a recent study of reentry in Boston found that 40 percent of a reentry program’s participants returned to just two neighborhoods.7 Ultimately, reentry experiences are shaped by class and racialized neighborhood segregation.

Although activists and communities have advocated for a response to mass incarceration for decades, it took a global pandemic to challenge surveillance and social control through policing and incarceration. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced jails and prisons to release thousands in an attempt to limit the devastating impact of viral spread in incarceration’s close living quarters.8 The need to reimagine reentry during this pandemic provides an opportunity to remove barriers to successful reentry while simultaneously addressing the broader racial disparities in our justice system.

Eliminating racial disparities in our criminal justice system and improving reentry outcomes requires a wholesale rethinking of our orientation toward criminal justice, rather than piecemeal reforms or isolated new programs. We must move away from a policy framework that focuses on punishment as a tool for controlling risk in favor of a focus on human rights, harm reduction, and the social, political, and economic reintegration of those who have been incarcerated. A well-developed, evidence-supported action plan for enhancing transitions from prison to society will focus on increasing independence, reducing racial and ethnic disparities, and achieving public safety. Our policy recommendations build upon the recent collective efforts that led to the First Step Act and the expansion of Federal Pell Grants eligibility for incarcerated people. We acknowledge that broader investments to level the playing field and foster more equitable access to quality education and economic opportunities are important to prevent incarceration in the first place and make it easier for those who are incarcerated to transition to employment after release. However, these wider policies to increase racial and economic equity are not the main focus of this brief.

Accordingly, our recommendations include:

Short-Term Reforms

- Prioritize vaccination in correctional facilities

- Ensure safe access to safety net programs for justice system impacted populations and use of COVID relief funding to address their barriers

- Expand access to the internet and digital skills needed during the pandemic

- Improve data sharing and service coordination

Medium-Term Reforms

- End restrictions on occupational licensing, safety net programs, and hiring for those with criminal records

- Expand and enforce anti-discrimination rules and regulations

- Enhance oversight and regulation of the criminal background check industry

- Increase funding for subsidized employment programs and American Job Centers

- Spur the creation of coordinated pre- to post-release education and work-based learning programs

- Update outdated security rules and technology policies in correctional facilities that limit the development of new rehabilitation programming

- Expand internet access in correctional facilities

- Modernize state and local data systems to improve service coordination and research

Long-Term Reforms

- Reorient parole and other forms of community supervision toward social and economic reintegration

- Increase access to services related to housing, employment, health/addiction, and social reintegration

- Improve rehabilitation services in correctional facilities by adopting a continuity of care model

- Expand funding for prison rehabilitation programming to meet demand

We must move away from a policy framework that focuses on punishment as a tool for controlling risk in favor of a focus on human rights, harm reduction, and the social, political, and economic reintegration of those who have been incarcerated.

Recommendations for change

Only 12 percent of prisoners are under federal jurisdiction. The remaining 88 percent are state prisoners.9This means that the conditions of imprisonment and support available for reentry vary greatly for different people and places, with important implications for equity. This also means that states are best positioned to make changes to many aspects of reentry policy. Yet the federal government can do more to improve reentry outcomes. First, federal officials can shape the public conversation by acknowledging the historical legacy of mass incarceration in the United States, emphasizing the humanity of people who are incarcerated, human rights, and giving people with conviction records a fair chance to succeed. Second, changes in federal reentry policies can serve as a model for states. Third, the federal government can provide funding for demonstration projects and more long-term funding streams to scale up proven reentry programs. Fourth, the federal government can change and enforce administrative rules and guidance for existing rules and laws, and develop new legislation to address gaps in authority, inequities in access, and a lack of consistent institutional infrastructure for supporting reentry. We note also that changes in policies with significant potential to improve reentry outcomes extend far beyond federal agencies traditionally involved in the administration of justice. Reentry barriers include housing, education, employment, health, and political rights.10

We divide our discussion into short, medium and long-term recommendations. The short-term recommendations pertain to existing funding streams and discretionary authority regarding administrative rules and regulations, funding decisions, and rule enforcement. The medium-term recommendations involve the creation of new legislation, infrastructure, and funding appropriations. Our long-term recommendations include changes in laws to achieve fundamental reorientations of existing policy frameworks and approaches that require substantial new funding appropriations.

Short-term Reforms

The global pandemic has profoundly impacted people in prisons and jails and their surrounding communities.11 Although jail and prison populations have decreased since the start of the pandemic, in many areas incarceration levels are beginning to return to pre-pandemic levels despite the unprecedented surge in cases and deaths.12

Reentry, in this context, is more challenging than it was before the pandemic in several respects:

- As facilities restrict visitors, access to reentry services is curtailed, and many states are not vaccinating, testing, or quarantining people upon release, putting people in transitional housing and the wider community at risk of COVID-19 exposure.13

- Basic social support systems such as food pantries, homeless services, and mental health services continue to be strained with increased demand, and many service providers have limited in-person services to protect public health.14This affects service access and quality for people with conviction records, especially in Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American communities that have been disproportionately impacted by over-incarceration and COVID-19.

- Less availability of jobs in the COVID-19 recession makes it harder for people with barriers to employment, including people with conviction records, to compete for jobs and secure employment.15

- Many education and service providers have shifted service delivery online to prevent community spread, but people with conviction records often face barriers to accessing online resources, including the lack of a stable internet connection or limited familiarity with technology.16

In the short-term, policymakers and government officials at all levels should take steps to prioritize vaccination in justice and detention facilities and renew the focus on minimizing the incarcerated population. Federal, state, and local policymakers should also consider more testing, quarantining, and targeted relief for people with conviction records who face barriers accessing federal stimulus payments, employment, unemployment insurance, safety net programs, and second chance relief.17 For example, state governors and/or agency secretaries could issue emergency guidance requiring that jails and prisons issue state IDs to qualified individuals and enroll eligible individuals in health insurance, food assistance, and career services prior to release.

In addition, facility staff and reentry providers should provide updated and consistent information about where to access support in the COVID-19 era, provide more training on digital skills, and increase coordination through direct handoffs to organizations providing support such as American Job Centers (AJCs), public health organizations, and reentry organizations. To the extent feasible, administration officials and state leaders should also reorient funding priorities to improve data sharing for service coordination, expand resources for secure broadband and technology access in prisons and jails, provide resources to expand Pell-funded education opportunities inside incarceration facilities, and make both pre-release and post-release protocols more flexible to accommodate the urgency of the crisis and elevated risk to human life.18

Medium-term Reforms

The stigma of a criminal record is one of the most important and well-documented barriers to successful reentry and reintegration,19 impacting not just employment but also housing,20 education,21 and access to the safety net.22 Stigma is both formal—prohibitions encoded in laws or regulations—and informal—impacting how formerly incarcerated individuals are evaluated by employers, landlords, and others.

There is substantial evidence that relief from criminal record stigma leads to improved outcomes, especially with regard to employment.23 The stigma of a criminal record represents a form of punishment beyond the formal sentence received from a court, one that has long-term impacts.

Consideration of a criminal record must be job-specific and justified, with a presumption that the criminal record is irrelevant. Current Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) guidelines recommend only considering the criminal record after a hiring decision has been made and only when the record itself is closely related to the job.24 Research suggests that many employers are unaware of these guidelines, necessitating greater education and enforcement.25 Ban-the-box laws, perhaps the most common policy to counter criminal record stigma in employment, have been shown to increase racial discrimination.26

To reduce the impact of criminal record stigma, we recommend the following:

- End restrictions on living in publicly subsidized housing for those with criminal records

- Expand the authority and budget of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to combat discrimination based on criminal record in employment and housing.

- Reform negligent-hiring laws that make employers hesitant to hire those with criminal records.27

- Blanket bans on applicants with criminal records should be prohibited. Ensure that local and state governments are in compliance.

- Appoint a blue ribbon commission to study and recommend reducing occupational licensing prohibitions, which are widespread and poorly justified.28

- Prohibit postsecondary institutions that receive federal funds from discriminating based on criminal records in admissions and hiring.

- Remove eligibility restrictions based on criminal record from federally funded safety-net programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, because access to these programs has been shown to reduce recidivism.29

- Enhance regulation of the criminal background check industry, as the consumer credit agencies are regulated, to improve the rights of individuals to correct information and to hold sellers of criminal record information responsible for its accuracy.30

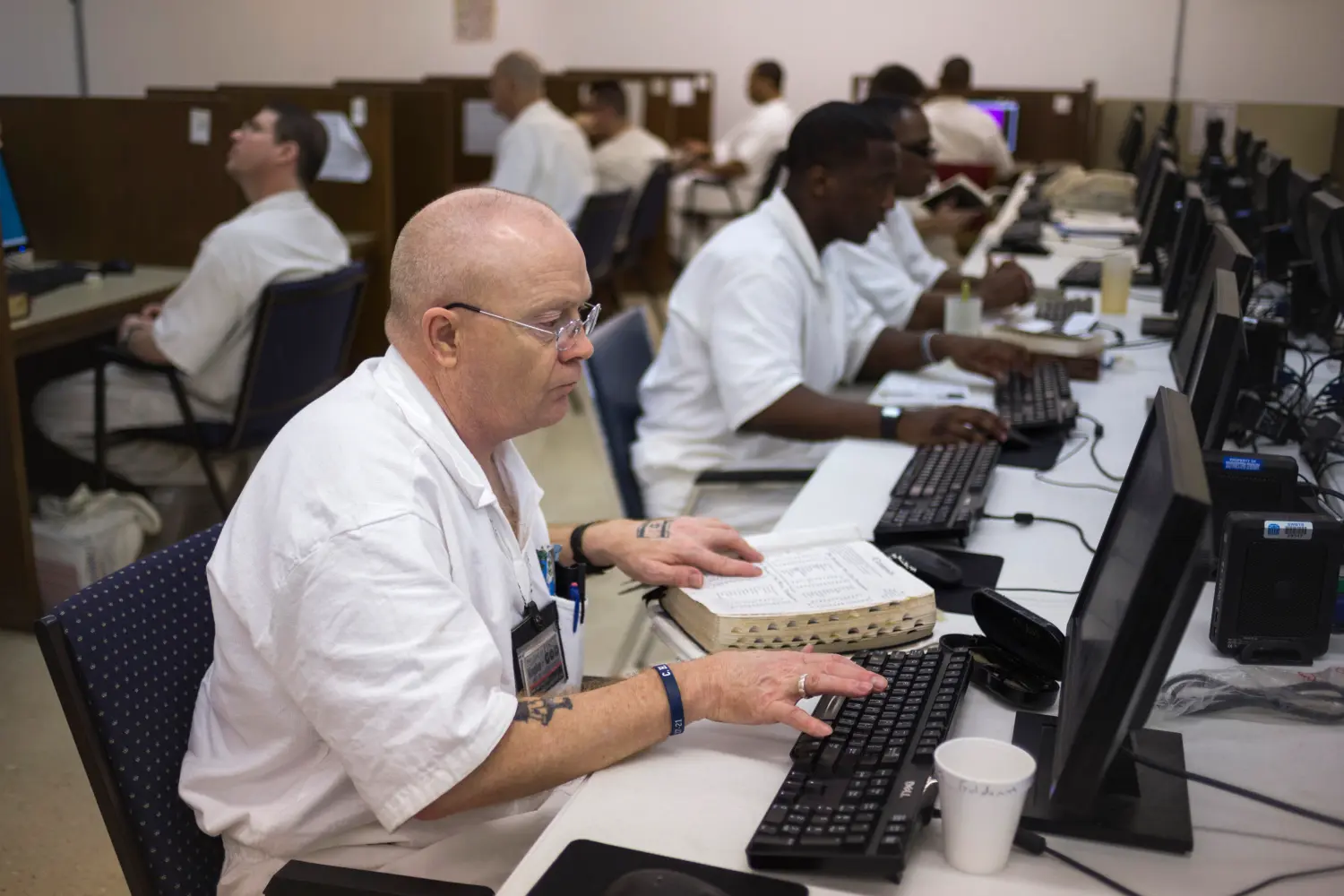

Stigma is not the only barrier to post-release employment, as the formerly incarcerated typically have low levels of education and work experience.31 Enhancing job search skills, job readiness, professional networks, and access to educational opportunities for the formerly incarcerated is essential to reentry success. One option is to increase work experience, enhance professional networks, and reduce hiring risk by expanding subsidized employment programs and programs that match employers with soon-to-be-released prisoners.32 Another option is to expand federal funding and incentivize the location of AJCs inside jails and prison facilities, building on the lessons from a recent U.S. Department of Labor demonstration project in 20 areas suggesting AJCs lead to gradual shifts in the culture within facilities from punishment to rehabilitation.33 Recent relief legislation lifted restrictions on Pell grant access for people who are incarcerated and who have certain crimes on their records, which can spur the creation of coordinated pre- to post-release education and work-based learning programs.34 In addition, formerly incarcerated people typically suffer from socially and economically induced traumas that can interfere with effective decisionmaking.35Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to improve reentry outcomes.36

Enhancing job search skills, job readiness, professional networks, and access to educational opportunities for the formerly incarcerated is essential to reentry success.

Finally, existing evidence on program development and implementation in correctional facilities suggests multiple avenues for jumpstarting the development and quality of new programs. First, establish consistently available and evidence-based reentry programs and provide additional flexibility with regard to outdated security rules and technology policies. For example, evidence suggests that cognitive behavioral therapy is effective for justice-involved adults for rehabilitation, self-confidence, and personal transformation.37 Second, lack of Internet access and overly rigid security protocols in some jails hindered the ability of several jails to implement satellite AJCs.38 Third, invest in broadband infrastructure, virtual reality (VR), and other technologies in prisons to improve access to online resources like job boards and online/VR training programs. Finally, invest in digital transformation and modernization of state-level data systems and revisit outdated restrictions on data sharing across programs and agencies (while protecting privacy). Antiquated and siloed data systems are a major barrier to service coordination and holistically meeting the needs of people with multiple challenges.39

Long-term Reforms

With the rise and entrenchment of mass incarceration came a change in the nature and goals of post-prison parole supervision, from a social work orientation to a law enforcement orientation that focuses on risk assessment and risk management.40 The parole system has now become a major obstacle to successful reentry through its emphasis on surveillance and punishment. Technical violations of parole and probation account for large shares of prison admissions in many states,41 and recent evidence suggests that the parole system is an important driver of prison’s revolving door.42 Lack of due process in parole revocation decisions also raises serious normative questions.43

Reforms are critically needed to reorient parole to support social and economic reintegration. Rather than monitoring for desistance, new policies should focus on creating opportunities to develop and reinforce pro-social identities.44 These reforms include increased access to services related to housing, employment, health, mental health and addiction, and social reintegration. They also provide greater options for less disruptive sanctions for technical parole violations and new national standards for the training of parole and probation officers in skills such as service coordination, motivational interviewing, alternatives to punishment, and counseling.45 Parolees would also benefit from opportunities to earn lower levels of supervision or early termination via completion of treatment programs or earning vocational or academic credentials.

A lack of preparation for release currently hinders reentry and reintegration. For example, demand for in-prison services in domains like substance abuse treatment and education far exceed supply despite the demonstrated effectiveness of such programs at reducing recidivism.46 And the effectiveness of such programs could be enhanced by adopting a “continuity of care” model common for medical treatment in which in-prison services are tied to parallel programs and supports in the community after release, facilitating effective handoffs.47 This model ensures continued access to support and receipt of long-term treatment, especially during the challenging period immediately after release, and reorients prison staff toward rehabilitation and release preparation.

We see “continuity of care” as potentially productive in domains like substance abuse treatment, family services, employment, and education. For example, identical substance abuse treatment models can improve post-release participation, college courses taught by the same institution in prison and in the community would ease enrollment post-release, and in-prison work that builds skills in industries with high labor demand in the community of release could improve employment. The location of prisons in rural areas, far from the prisoners’ families and communities, also creates barriers to continuity of care and the involvement of families, who play a central role in reintegration.48 Ensuring continuity of care will require investment in bringing programs up to scale and in policy alignment and coordination across domains and levels of government. The federal government could spur innovation by providing technical expertise and funding for coordination and ensuring that rules and regulations do not impede cooperation between prisons and community providers.

Recommendations for future research

Although there is a growing academic and evaluation literature on reentry experiences and programs, we still need to better understand a diverse range of reentry experiences, the factors and practices that lead to better or more equitable outcomes, and the legal and policy barriers that undermine the goal of shifting from a culture of continual punishment to a culture of rehabilitation and reintegration. Below we lay out research priorities in each of these broad areas where there are significant gaps.

1. Reentry experiences: Existing research suggests that some populations experience more barriers than others in reintegrating into society, but there is a need for more in-depth research on the experiences of racial/ethnic minorities, women (especially Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American women), people with disabilities (including cognitive and mental health disabilities), LGBTQ individuals, young adults, people released in rural areas, gig workers, and those whose intersectional identities create multiple barriers to successful reentry.

2. Factors and practices that influence outcomes:

- Pandemic impacts: How did the pandemic change policies such as fewer arrests and more releases, and what were the impacts of those changes on community safety and wellbeing of the individuals who were released? How did the uneven impacts of the pandemic in Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American communities shape reentry experiences for those who were released into the same communities? Stigma: How to reduce stigma among employers, landlords, and the media as well as documenting the impacts of stigma on individuals, families, and communities?

- Parole officers and other justice system actors: How do their training, mindset, and incentive structures support or undermine successful reentry?

- Intermediate sanctions: When are they helpful and when do they simply provide pathways back to prison (“net widening”)?

- Fair chance hiring: How do hiring practices differ among employers with more and less employees with conviction records? How does the use of artificial intelligence in hiring and recruitment impact people with conviction records?

- Industry-specific factors: How do occupational segregation, discrimination, and licensing requirements contribute to more limited employment options for certain groups of people with conviction records (e.g., women and Black or Latino or Hispanic)?

3. Legal and policy barriers: Although there is bipartisan support and evidence to maximize reentry success, our legacy legal and policy frameworks often undermine these new goals as an artifact of the previous emphasis on punishment. Rather than focusing on desistance from crime, our legal and policy frameworks should emphasize opportunities to create and affirm pro-social identities. More research is needed to unpack a litany of federal, state, and local laws and policies to identify barriers that tend to undermine efforts at establishing pro-social identities and reintegration.49 This includes housing, voting, financial aid, and food assistance restrictions that render people with conviction records ineligible. In addition, it means ensuring that people who have conviction records have more legal protections and entitlements across various areas of everyday life, which may require identifying legal cases with potential to revisit central legal questions such as whether it is legal to discriminate on the basis of a conviction record for access to housing or if housing is a basic human right that is essential for reentry success. As another example, to what extent are transitional housing facilities allowed to establish curfews and or place restrictions on the possession of personal belongings such as technology, if doing so undermines someone’s ability to get or keep a job or rebuild personal and professional networks? Are prison wages of pennies per hour desirable from a policy or normative perspective?

Moreover, reentry research would benefit from consistent measurement of outcomes and accessible, user-friendly data systems to track outcomes and coordinate services across multiple agencies and programs that play a role in the reentry ecosystem. Although there have been major investments in research on the effectiveness of reentry programs, it is challenging to compare across studies because they often do not systematically assess outcomes in the same ways, may only assess one aspect of reentry success, or only assess short-term impacts.50 Common barriers to the implementation of reentry services include lack of coordination across partners, inadequate resources, variation in intensity and scope of services across areas, and a lack of data systems and secure data sharing.515253 Subsidized employment programs offer promising evidence of short-run success, but less is known about the factors that contribute to long-term impacts in employment, earnings, and reduced recidivism.54

Finally, there are many new technology-oriented changes and pilots that are worth studying and evaluating. For example, Code for America partnered with local governments to expunge records for offenses that are no longer illegal.55 Research is needed to assess how these tools can help improve the implementation of second chance relief.56 In addition, virtual reality and other technologies are being deployed in multiple states to prepare people for release through immersive exposure to scenarios they are likely to encounter and for training and education.5758As new background search techniques are deployed with machine learning technologies,59 research is needed to assess their ethical and discriminatory impacts, and to develop regulatory standards for their use. More research and funding are needed to evaluate these technologies, assess quality and ethical use, and update policy in response.

Recommended Reading

Center for Justice Research and Black Public Defender Association. Save Black Lives: A Call for Racially-Responsive Strategies and Resources for the Black Community during COVID-19 Pandemic. Houston, TX: Texas Southern University, 2020. Available at: https://www.centerforjusticeresearch.org/reports/save-black-lives

Cummings, Danielle, and Dan Bloom. Can Subsidized Employment Programs Help Disadvantaged Job Seekers? A Synthesis of Findings from Evaluations of 13 Programs. MDRC, OPRE Report 2020–23. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2020. Available at: www.mdrc.org/publication/can-subsidized-employment-programs-help-disadvantaged-job-seekers.

Gould-Werth, Alix, Samina Sattar, Jennifer Henderson-Frakes, et al. LEAP Issue Brief Compendium: Delivering Workforce Services to Justice-Involved Job Seekers Before and After Release. Mathematica Policy Research and Social Policy Research Associates 2018. Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA. Available at: https://www.mathematica.org/our-publications-and-findings/publications/leap-issue-brief-compendium-delivering-workforce-services-to-justice-involved-job-seekers-before

Mallik-Kane, Kamala, and Christy Ann Visher. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Washington, DC: Urban Institute and Justice Policy Center, 2008.

Lacoe, Johanna and Hannah Betesh. Supporting Reentry Employment and Success: A Summary of the Evidence for Adults and Young Adults. Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA: Mathematica Policy Research by Social Policy Research Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/REOSupportingReentryEmploymentRB090319.pdf

National Research Council. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2014.

United Nations. UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules), 1957. New York, 1975. Available at: https://www.penalreform.org/resource/standard-minimum-rules-treatment-prisoners-smr/

Western, Bruce. “Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison”. Russell Sage Foundation, 2018.

Pew Charitable Trusts. Policy Reforms Can Strengthen Community Supervision: A framework to improve probation and parole, 2020. Available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2020/04/policyreform_communitysupervision_report_final.pdf

Harding David J., Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Jessica J.B. Wyse. “On the Outside: Prisoner Reentry and Reintegration”. University of Chicago Press, 2019.

-

Footnotes

- James, Nathan. “Offender Reentry: Correctional Statistics, Reintegration into the Community, and Recidivism”, 2015. Correctional Research Service, RL34287. Available at: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34287.pdf.

- Ramakers, Anke A. T., et al., “Returning to a Former Employer: A Potentially Successful Pathway to Ex-prisoner Re-employment,” The British Journal of Criminology, vol. 56, no. 4, 2016, pp. 668–688. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv063.

-

Gaes, Gerald G., and Newton Kendig. From prison to home: The effect of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities: The skill sets and health care needs of released offenders. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2002;

Landenberger, N. A., & Lipsey, M. W. “The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment.” Journal of experimental criminology. vol. 1, no. 4, 2005, pp. 451–476. Available at: doi:10.1007/s11292-005-3541-7.;

Mallik-Kane, Kamala, and Christy A. Visher. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration, 2008. Washington, DC: Urban Institute & Justice Policy Center, p. 82, 2008. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/31491/411617-Health-and-Prisoner-Reentry.PDF.

Yang, Crystal S. “Does public assistance reduce recidivism?” American Economic Review, vol. 107, no. 5, 2017, pp.551–55; Council of State Governments Justice Ctr. Reducing recidivism: States deliver results, 2018. Available at: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/papers/pdf/Yang_920.pdf.

Link, N. W., Ward, J. T., & Stansfield, R. 2019. “Consequences of mental and physical health for reentry and recidivism: Toward a health‐based model of desistance.” Criminology, vol. 57, no. 3, 2019, 544–573. Available at: doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12213.

Couloute, Lucius, and Daniel Kopf. “Out of prison & out of work: Unemployment among formerly incarcerated people,” Prison Policy Initiative, 2018, Accessed 12 April 2021. Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html - Clear, Todd. R. Studies in crime and public policy. Imprisoning communities: How mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Sampson, R. J., & Loeffler, C. “Punishment’s place: the local concentration of mass incarceration.” Daedalus, vol. 139, no. 3, 2010, pp. 20–31. Available at: doi:10.1162/daed_a_00020.

- Simes, Jessica Tayloe. “Essays on Place and Punishment in America.” Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, 2016.

- Sampson, Robert J., William Julius Wilson, and Hanna Katz . “Reassessing ‘Toward A Theory of Race, Crime, and Urban Inequality:’ Enduring and New Challenges in 21st Century America.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, vol. 15, no. 1, 2018, pp. 13–34. Available at: doi:10.1017/s1742058x18000140.

- Center for Justice Research and Black Public Defender Association. Save Black Lives: A Call for Racially-Responsive Strategies and Resources for the Black Community during COVID-19 Pandemic, 2020. Houston, TX: Texas Southern University.

- Carson, Ann E. Prisoners in 2019. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2020, NCJ 255115. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf.

- Visher, Christy A., and Jeremy Travis. “Transitions from prison to community: Understanding individual pathways.” Annual review of sociology, vol. 29, no. 1, 2003, pp. 89–113.

- Lewis, Nicole, and Beth Schwartzapfel. “Prisons Are Releasing People Without COVID-19 Tests Or Quarantines.” The Marshall Project, 19 Jan. 2021. Available at: www.themarshallproject.org/2021/01/19/prisons-are-releasing-people-without-covid-19-tests-or-quarantines.

- Initiative, Prison Policy. “As COVID-19 Continues to Spread Rapidly, State Prisons and Local Jails Have Failed to Mitigate the Risk of Infection behind Bars.” Prison Policy Initiative, 2 Dec. 2020. Available at: www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/02/jail-and-prison-covid-populations.

- Lewis, Nicole, and Beth Schwartzapfel. “Prisons Are Releasing People Without COVID-19 Tests Or Quarantines.” The Marshall Project, 19 Jan. 2021. Available at: www.themarshallproject.org/2021/01/19/prisons-are-releasing-people-without-covid-19-tests-or-quarantines.

- Feeding America. “Food Banks Responding to Rising Need | Feeding America.” Feeding America, 22 Dec. 2020, Available at: www.feedingamerica.org/about-us/press-room/nine-months-later-food-banks-continue-responding-rising-need-help.

- Max, Samantha. “Those Released from Prison Find Reentry Much Harder Due to COVID-19.” Marketplace, 14 July 2020. Available at: www.marketplace.org/2020/07/14/covid-19-prison-inmates-reentering-society.

- San Francisco State University Project Rebound. “Lessons from Formerly Incarcerated Students During COVID-19.” Associated Students, Accessed 12 April 2021. Available at: http://asi.sfsu.edu/project-rebound-covid-19-support/.

- Chien, Colleen V., “America’s Paper Prisons: The Second Chance Gap (December 16, 2020).” Michigan Law Review, Forthcoming. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3265335.

- Note: An estimated 74 percent of people incarcerated in jails are in pre-trial detention. The recommendation for providing job center support, education, and other reentry services in jails is most pertinent to the 26 percent of the jail population who have been sentenced. Other policies are necessary for prevention and to minimize the jail population in pre-trial detention, but they are outside the scope of this brief. Source: Sawyer, Wendy, and Peter Wagner. “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2020.” Prison Policy Initiative, 24 Mar. 2020. Available at: www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html#slideshows/slideshow1/2.

-

Jacobs, James B. The Eternal Criminal Record. Harvard University Press, 2015.;

Pager, Devah. Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in the Era of Mass Incarceration. University of Chicago Press, 2007. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo5485761.html. - Evans, Douglas N., et al. “Examining Housing Discrimination across Race, Gender and Felony History.” Housing Studies, vol. 34, no. 5, 2018, pp. 761–78. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2018.1478069.

- Stewart, Robert, and Christopher Uggen. “Criminal Records and College Admissions: A Modified Experimental Audit.” Criminology, vol. 58, no. 1, 2019, pp. 156–88. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12229.

- Schanzenbach, Diane, et al. Twelve Facts about Incarceration and Prisoner Reentry. The Hamilton Project, 2016. Accessed 12 April 2021. Available at: https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/12_facts_about_incarceration_prisoner_reentry.pdf.

-

Denver, Megan, Garima Siwach, and Shawn D. Bushway. “A new look at the employment and recidivism relationship through the lens of a criminal background check.” Criminology, vol. 55, 2017, pp. 174–204. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12130.

Prescott, J. J. and Sonja Starr. “Expungement of Criminal Convictions: An Empirical Study.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 133, no. 8, 2020, pp. 2460–2555. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1745-9125.12130. - EEOC. U.S Equal Employment Opportunity Commission enforcement guide, 2012. no. 915.002.

- Pager, Devah. Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in the Era of Mass Incarceration. University of Chicago Press, 2007. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo5485761.html.

-

Agan, A. and Sonja Starr. “Ban the box, criminal records, and racial discrimination: A field experiment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 133, no. 1, 2018, pp. 191–235. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx028.

Doleac, Jennifer L., and Benjamin Hansen. “The unintended consequences of “ban the box”: Statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when criminal histories are hidden.” Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 38, no. 2, 2020, pp. 321-374. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/705880. - Bushway, Shawn D. and Nidhi Kalra. “A Policy Review of Employers; Open Access to Conviction Records.” Annual Review of Criminology, vol. 4, 2021, no. 16.1–16.25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-061020-021622.

- Lucken, K. and Ponte, L.M. “A Just Measure of Forgiveness: Reforming Occupational Licensing Regulations for Ex‐Offenders Using BFOQ Analysis.” Law & Policy, vol. 30, 2008, pp. 46–72. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9930.2008.00269.x.

- Yang, Crystal S. “Does public assistance reduce recidivism?“ American Economic Review, vol. 107, no. 5, 2017, pp.551–55. Available at: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/papers/pdf/Yang_920.pdf.

-

Bushway, Shawn; Shauna Briggs, Faye Taxman, Meridith Thanner, and Mischelle Van Brakle. “Private Providers of Criminal History Records: Do You Get What You Pay For?” in Bushway, Shawn, Michael Stoll, and David Weiman (eds.) The Impact of Incarceration on Labor Market Outcomes. Russell Sage Foundation Press, 2007, p. 174–200.;

Lageson, Sarah E. Digital Punishment: Privacy, Stigma, and the Harms of Data-Driven Criminal Justice. Oxford University Press, 2020. -

Bushway, Shawn, Michael Stoll, and David Weiman (eds.) The Impact of Incarceration on Labor Market Outcomes. Russell Sage, 2007.

Travis, Jeremy. But They All Come Back: Facing the Challenges of Prisoner Reentry, 2005. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press. -

Cummings, Danielle, and Dan Bloom. Can Subsidized Employment Programs Help Disadvantaged Job Seekers? A Synthesis of Findings from Evaluations of 13 Programs. MDRC, OPRE Report 2020–23. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2020. Available at: www.mdrc.org/publication/can-subsidized-employment-programs-help-disadvantaged-job-seekers.

Foley, Kimberly, Mary Farrell, Riley Webster, and Johanna Walter. Reducing Recidivism and Increasing Opportunity. Benefits and Costs of the RecycleForce Enhanced Transitional Jobs Program. MDRC, MEF Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/ETJD_STED_Benefit_Cost_Brief_508.pdf.

Redcross, Cindy, Megan Millenky, Timothy Rudd, and Valerie Levshin. More than a job: Final results from the evaluation of the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) transitional jobs program. OPRE Report, 2011–18. New York, NY: MDRC and Vera Institute, 2012. Available at: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_451.pdf.

Dutta-Gupta, Indivar, Kali Grant, Matthew Eckel, and Peter Edelman, P. Lessons learned from 40 years of subsidized employment programs: A framework, review of models, and recommendations for helping disadvantaged workers. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Law, Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2016. Available at: https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GCPI-Subsidized-Employment-Paper-20160413.pdf. - Bellotti, Jeanne, et al. Developing American Job Centers in Jails: Implementation of the Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release LEAP) Grants. Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA: Mathematica Policy Research and Social Policy Research Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GCPI-Subsidized-Employment-Paper-20160413.pdf.

- See also Duwe, Grant and Makada Henry-Nickie, “Training and Employment for Correctional Populations,” in chapter 6 of this report.

- Western, Bruce. Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison. Russell Sage Foundation, 2018.

- Lacoe, Johanna and Hannah Betesh. “Supporting Reentry Employment and Success: A Summary of the Evidence for Adults and Young Adults.” Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA: Mathematica Policy Research by Social Policy Research Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/REOSupportingReentryEmploymentRB090319.pdf.

- Lacoe, Johanna and Hannah Betesh. “Supporting Reentry Employment and Success: A Summary of the Evidence for Adults and Young Adults.” Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA: Mathematica Policy Research by Social Policy Research Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/REOSupportingReentryEmploymentRB090319.pdf.

- Bellotti, Jeanne, et al. Developing American Job Centers in Jails: Implementation of the Linking to Employment Activities Pre-Release LEAP) Grants. Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA: Mathematica Policy Research and Social Policy Research Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.mdrc.org/publication/can-subsidized-employment-programs-help-disadvantaged-job-seekers.

- Sinkewicz, Marilyn, Yu-Fen Chiu, and Leah Pope. Sharing Behavioral Health Information Across Justice and Health Systems. Vera Institute of Justice, 2018. Available at: https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/Sharing-Behavioral-Health-Information-across-Justice-and-Health-Systems-Full-Report.pdf. Milgram, Anne, Jeffrey Brenner, Dawn Wiest, Virginia Bersch, and Aaron Truchil. Integrated Health Care and Criminal Justice Data: Viewing the Intersection of Public Safety, Public Health, and Public Policy Through a New Lens: Lessons from Camden, New Jersey. Harvard Kennedy School, Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management, 2018. Available at: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/wiener/programs/pcj/files/integrated_healthcare_criminaljustice_data.pdf.

-

Garland, David. The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Simon, Jonathan. Poor Discipline. University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Petersilia, Joan. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. Oxford University press, 2003. - Carson, Ann E. Prisoners in 2019. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2020, NCJ 255115. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p19.pdf.

- Harding, David J., et al. “The short- and long-term effects of imprisonment on future felony convictions and prison admissions,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2017. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/114/42/11103.

- Margaret J. Frossard. “The Detainer Process: The Hidden Due Process Violation in Parole Revocation,” 1976. 52 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 716. Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol52/iss3/11/.

- Bushway, Shawn D., and Raymond Paternoster. “Desistance from Crime: A Review and Ideas for Moving Forward.” In: Gibson C., Krohn M. (eds.) Handbook of Life-Course Criminology. Springer, 2013. Available at: doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5113-6_13.

- Pew Charitable Trusts. Policy Reforms Can Strengthen Community Supervision: A framework to improve probation and parole, 2020. Available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2020/04/policyreform_communitysupervision_report_final.pdf.

-

California State Auditor. “California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation: Several Poor Administrative Practices Have Hindered Reductions in Recidivism and Denied Inmates Access to In‑Prison Rehabilitation Programs.” 2019, Report 2018-113. Available at: https://www.bsa.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2018-113.pdf.

Mukamal, Debbie, Rebecca Silbert and Rebecca M. Taylor. “Degrees of Freedom: Expanding College Opportunities for Currently and Formerly Incarcerated Californians, 2015. Available at: https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=child-page/443444/doc/slspublic/DegreesofFreedom2015_FINAL.pdf.

Stanford Criminal Justice Center. Corrections to College California. “Don’t Stop Now: California leads the nation in using public higher education to address mass incarceration. Will we continue?” 2018. Available at: https://risingscholarsnetwork.org/assets/general/dont-stop-now-report_v2.pdf.

Pompoco, Amanda, John Wooldredge, Melissa Lugo, et al. “Reducing Inmate Misconduct and Prison Returns with Facility Education Programs.” Criminology & Public Policy, vol. 16, 2017, pp. 515-547. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12290.

Mackenzie, Doris L. What Works in Corrections. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Petersilia, Joan. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. Oxford University press, 2003.

Wexler, Harry K., Gregory P. Falkin, and Douglas S. Lipton. Outcome Evaluation of a Prison Therapeutic Community for Substance Abuse Treatment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, vol. 17, no. 1, 1990, pp. 71–92.

Stainbrook, Kristin, Jeanine Hanna, and Amy Salomon. The Residential Substance Abuse Treatment (RSAT) Study: The Characteristics and Components of RSAT Funded Treatment and Aftercare Services: Final Report. New York, NY: Advocates for Human Potential, 2017. Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/250715.pdf. - Visher, Christy A., et al. “Evaluating the Long-Term Effects of Prisoner Reentry Services on Recidivism: What Types of Services Matter?” Justice Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1, 2016, pp. 136–65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2015.1115539.

- Harding, David J., Morenoff, Jeffrey D., and Jessica J.B. Wyse. “On the Outside: Prisoner Reentry and Reintegration.” University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- Bushway, Shawn D. and Raymond Paternoster, “Desistance from Crime: A Review and Ideas for Moving Forward.” In: Gibson C., Krohn M. (eds.) Handbook of Life-Course Criminology. Springer, 2013. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5113-6_13.

- Lacoe, Johana, and Hannah Betesh. “Supporting Reentry Employment and Success: A Summary of the Evidence for Adults and Young Adults.” Princeton, NJ and Oakland, CA: Mathematica Policy Research by Social Policy Research Associates, 2019. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/REOSupportingReentryEmploymentRB090319.pdf.

- D’Amico, Ronald and Hui Kim. “Evaluation of Seven Second Chance Act Adult Demonstration Programs: Impact Findings at 30 Months”. Oakland, CA: Social Policy Research Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/251702.pdf.

- Fontaine, Jocelyn, et al. “Safer Return Demonstration: Impact Findings from a Research-Based Community Reentry Initiative”, Washington, D.C: Urban Institute, 2015. Available at: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/56296/2000276-Safer-Return-Demonstration-Impact-Findings-from-the-Research-Based-Community-Reentry-Initiative.pdf.

- Milgram, Anne, et al., “Integrated Health Care and Criminal Justice Data: Viewing the Intersection of Public Safety, Public Health, and Public Policy Through a New Lens: Lessons from Camden, New Jersey. Harvard Kennedy School, Program in Criminal Justice Policy and Management.” Harvard Kennedy School, Papers from the Executive Session on Community Corrections, April 2018. Available at: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/wiener/programs/pcj/files/integrated_healthcare_criminaljustice_data.pdf.

- Cummings, Danielle, and Dan Bloom. Can Subsidized Employment Programs Help Disadvantaged Job Seekers? A Synthesis of Findings from Evaluations of 13 Programs. MDRC, OPRE Report 2020–23. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2020. Available at: www.mdrc.org/publication/can-subsidized-employment-programs-help-disadvantaged-job-seekers.

- Toran-Burrell, Toran-Burrell, Alia, and David Crawford. “Record Clearance at Scale: How Clear My Record Helped Reduce or Dismiss 144,000 Convictions in California.” Code for America, 23 Sept. 2020. Available at: www.codeforamerica.org/news/record-clearance-at-scale-how-clear-my-record-helped-reduce-or-dismiss-144-000-convictions-in-california.

- Chien, Colleen V., “America’s Paper Prisons: The Second Chance Gap” December 16, 2020. 119 MICH. L. REV. 519 (2020), Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3265335.

- Institute for the Future. “IFTF: {VR} for Reentry.” Institute for the Future, 2021. Available at: www.iftf.org/vrforreentry.

- Smith, Matthew J., et al. “Enhancing Vocational Training in Corrections: A Type 1 Hybrid Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol for Evaluating Virtual Reality Job Interview Training among Returning Citizens Preparing for Community Re-Entry.” Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, vol. 19, no. 2451–8654, 2020, p. 100604. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100604.

- Dattner, Ben, et al. Harvard Business Review. The Legal and Ethical Implications of Using AI in Hiring, 25 Apr. 2019. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/04/the-legal-and-ethical-implications-of-using-ai-in-hiring.

Landenberger, N. A., & Lipsey, M. W. “The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: A meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment.” Journal of experimental criminology. vol. 1, no. 4, 2005, pp. 451–476. Available at: doi:10.1007/s11292-005-3541-7.;

Mallik-Kane, Kamala, and Christy A. Visher. Health and prisoner reentry: How physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration, 2008. Washington, DC: Urban Institute & Justice Policy Center, p. 82, 2008. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/31491/411617-Health-and-Prisoner-Reentry.PDF.

Yang, Crystal S. “Does public assistance reduce recidivism?” American Economic Review, vol. 107, no. 5, 2017, pp.551–55; Council of State Governments Justice Ctr. Reducing recidivism: States deliver results, 2018. Available at: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/olin_center/papers/pdf/Yang_920.pdf.

Link, N. W., Ward, J. T., & Stansfield, R. 2019. “Consequences of mental and physical health for reentry and recidivism: Toward a health‐based model of desistance.” Criminology, vol. 57, no. 3, 2019, 544–573. Available at: doi:10.1111/1745-9125.12213.

Couloute, Lucius, and Daniel Kopf. “Out of prison & out of work: Unemployment among formerly incarcerated people,” Prison Policy Initiative, 2018, Accessed 12 April 2021. Available at: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/outofwork.html

Pager, Devah. Marked: Race, Crime, and Finding Work in the Era of Mass Incarceration. University of Chicago Press, 2007. Available at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/M/bo5485761.html.

Prescott, J. J. and Sonja Starr. “Expungement of Criminal Convictions: An Empirical Study.” Harvard Law Review, vol. 133, no. 8, 2020, pp. 2460–2555. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1745-9125.12130.

Doleac, Jennifer L., and Benjamin Hansen. “The unintended consequences of “ban the box”: Statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when criminal histories are hidden.” Journal of Labor Economics, vol. 38, no. 2, 2020, pp. 321-374. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/705880.

Lageson, Sarah E. Digital Punishment: Privacy, Stigma, and the Harms of Data-Driven Criminal Justice. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Travis, Jeremy. But They All Come Back: Facing the Challenges of Prisoner Reentry, 2005. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Foley, Kimberly, Mary Farrell, Riley Webster, and Johanna Walter. Reducing Recidivism and Increasing Opportunity. Benefits and Costs of the RecycleForce Enhanced Transitional Jobs Program. MDRC, MEF Associates, 2018. Available at: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/ETJD_STED_Benefit_Cost_Brief_508.pdf.

Redcross, Cindy, Megan Millenky, Timothy Rudd, and Valerie Levshin. More than a job: Final results from the evaluation of the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) transitional jobs program. OPRE Report, 2011–18. New York, NY: MDRC and Vera Institute, 2012. Available at: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_451.pdf.

Dutta-Gupta, Indivar, Kali Grant, Matthew Eckel, and Peter Edelman, P. Lessons learned from 40 years of subsidized employment programs: A framework, review of models, and recommendations for helping disadvantaged workers. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Law, Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2016. Available at: https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/GCPI-Subsidized-Employment-Paper-20160413.pdf.

Simon, Jonathan. Poor Discipline. University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Petersilia, Joan. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. Oxford University press, 2003.

Mukamal, Debbie, Rebecca Silbert and Rebecca M. Taylor. “Degrees of Freedom: Expanding College Opportunities for Currently and Formerly Incarcerated Californians, 2015. Available at: https://law.stanford.edu/index.php?webauth-document=child-page/443444/doc/slspublic/DegreesofFreedom2015_FINAL.pdf.

Stanford Criminal Justice Center. Corrections to College California. “Don’t Stop Now: California leads the nation in using public higher education to address mass incarceration. Will we continue?” 2018. Available at: https://risingscholarsnetwork.org/assets/general/dont-stop-now-report_v2.pdf.

Pompoco, Amanda, John Wooldredge, Melissa Lugo, et al. “Reducing Inmate Misconduct and Prison Returns with Facility Education Programs.” Criminology & Public Policy, vol. 16, 2017, pp. 515-547. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12290.

Mackenzie, Doris L. What Works in Corrections. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Petersilia, Joan. When Prisoners Come Home: Parole and Prisoner Reentry. Oxford University press, 2003.

Wexler, Harry K., Gregory P. Falkin, and Douglas S. Lipton. Outcome Evaluation of a Prison Therapeutic Community for Substance Abuse Treatment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, vol. 17, no. 1, 1990, pp. 71–92.

Stainbrook, Kristin, Jeanine Hanna, and Amy Salomon. The Residential Substance Abuse Treatment (RSAT) Study: The Characteristics and Components of RSAT Funded Treatment and Aftercare Services: Final Report. New York, NY: Advocates for Human Potential, 2017. Available at: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/250715.pdf.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).