As college application season kicks off, students and families across the country will be carefully weighing their academic—and financial—options. More students than ever before are attending college in the U.S., and a growing number of them are taking out loans to fund their studies. This increase in borrowing has led families, the media, and presidential candidates alike to join a mounting chorus of concern over student debt and what it means for those who incur it.

But are we actually in the midst of a “student debt crisis?” In a new paper published in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis examine new longitudinal government data on the debt held by four million student loan borrowers since 1970 to shed some light on who exactly is borrowing—and defaulting—the most. Here are five facts they uncovered about student debt in America:

1.

Student borrowing has surged in the past several decades.

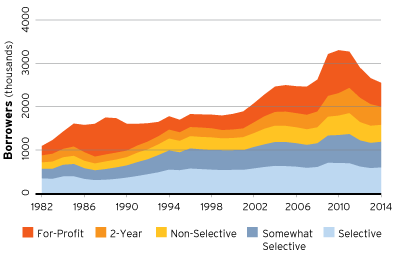

Student borrowing (along with the number of students enrolled) has been increasing over the past few decades, and between 2000 and 2014, the total volume of outstanding federal student debt nearly quadrupled to surpass $1.1 trillion. In this same time period, the number of student borrowers more than doubled to 42 million, and default rates among recent borrowers rose to their highest levels in 20 years.

2.

For-profit and two-year institutions are a growing part of the debt problem

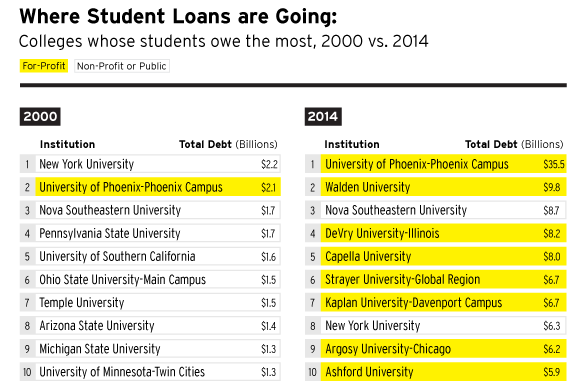

Since 2000, there has been an upsurge in the number of “nontraditional borrowers” attending for-profit schools and, to a lesser extent, community colleges and other non-selective institutions. In 2000, only 1 of the top 25 schools whose students owed the most federal debt was a for-profit institution, whereas in 2014, 13 were. Borrowers from those 13 schools owed about $109 billion—almost 10 percent of all federal student loans.

3.

Borrowers at for-profit and two-year schools are the most likely to default on their loans.

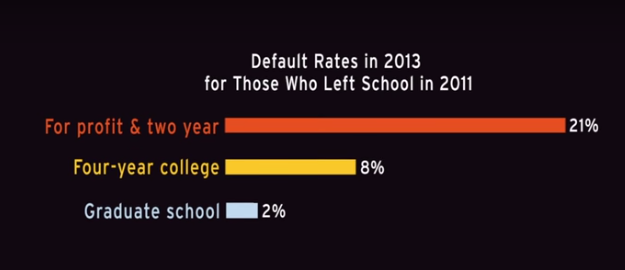

The research showed that in 2013, 21 percent of the borrowers who attended for-profit and community colleges defaulted on their loans within two years, compared to only 8 percent of those who went to four-year colleges and only two percent of those who attended graduate school.

4.

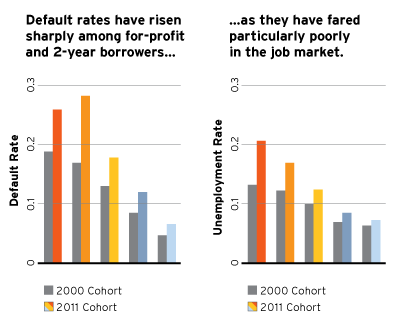

Borrowers at for profit and two year colleges fared poorly in the job market, making it harder to pay off their loans.

Students who borrowed substantial amounts to attend for-profit and community college were more likely to drop out of their programs and experienced poor labor market outcomes that made their debt burdens difficult to sustain. More than 25 percent of them left school during or soon after the recession and defaulted on their loans within three years.

5.

The good news: These borrowing and default trends are not likely to continue.

But according to Looney and Yannelis, things are looking up: The number of new borrowers at for-profit and two-year institutions is currently dropping due to the end of the recession and because of increased oversight of the for-profit sector, which is likely to decrease the risk of default for future borrowers.

In fact, some substantial efforts have already been made to keep critical funds out of for-profit schools: On October 8, 2015 the Department of Defense (DoD) announced that it would no longer allow the for-profit University of Phoenix to recruit on military bases, and that no new or transfer students will be permitted to receive DoD tuition assistance at the school.

Watch David Wessel, the director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at Brookings explain more about the student debt crisis:

Read the full BPEA paper

, A crisis in student loans? How changes in the characteristics of borrowers and in the institutions they attended contributed to rising loan defaults here.

And learn more about student in the U.S. from the Brookings Brown Center on Education Policy here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

5 facts about student debt in the U.S.

October 13, 2015