The following is the prologue to the 2018 Brown Center Report on American Education.

American schools find themselves immersed in politics in 2018. A horrific shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida sparked a wave of student demonstrations, culminating in hundreds of thousands of students descending on Washington, D.C., for the March for Our Lives. A controversial president and his controversial secretary of education have aroused passions on issues including the deportation of young immigrants, civil rights protections for transgender children, and schools’ handling of bullying and student discipline. Meanwhile, unrest among teachers has yielded rallies and strikes across the country.

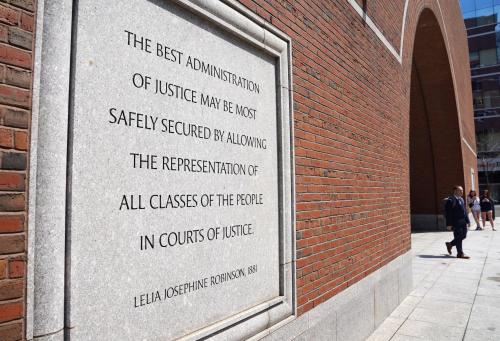

This, in other words, is a time of heightened political awareness and activity in schools. It is also a time of heightened concern about the state of U.S. politics and democracy. The 2016 election drew attention to the increasing polarization and divisiveness of our politics, and to the susceptibility of American voters’ beliefs to false or misleading information. These concerns have raised important questions about K-12 education in America. Are schools equipping students with the tools to become engaged, informed, and compassionate citizens? Are they equipping some students, or groups of students, better than others?

For all of their flaws, past and present, U.S. public schools have a long history of responding to the perceived needs of the time. Nineteenth-century common schools arose from a desire to create social harmony and political stability, amid strife, by instilling a common set of values and beliefs through public education. A century later, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act to bolster science education and better align school priorities with national priorities. And when “A Nation at Risk” brought attention to American students’ disappointing performance on international tests, states began to adopt content standards and measure students’ progress on tests aligned with those standards.

This is a time of heightened political awareness and activity in schools. It is also a time of heightened concern about the state of U.S. politics and democracy.

A growing sentiment holds that many of the country’s greatest challenges today relate to the state of its politics, with implications for the cohesion of American society and functioning of its democracy. However, even as politics increasingly penetrate American classrooms, U.S. education policy—as implemented in state accountability systems, for example—continues to emphasize students’ performance in mathematics and reading as the dominant focus of K-12 schooling. To the extent this emphasis has crowded out a focus on students’ civic development, we should ask whether today’s schools are, in fact, responsive to the needs of our time.

This edition of the Brown Center Report (BCR) on American Education focuses on the state of social studies and civics education in U.S. schools. Like previous editions, which were authored by Tom Loveless, this report examines student performance on a recent assessment—the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)—before delving into distinct topics in subsequent sections, each of which focuses on a different aspect of civics education.

Specifically, the 2018 BCR is organized as follows:

- Chapter 1 assesses trends in students’ scores on the NAEP, colloquially known as the “Nation’s Report Card.” The 2017 NAEP has drawn particular interest for demarcating the end of the No Child Left Behind era and the beginning of the Every Student Succeeds Act era. This chapter describes trends in standardized scores on the mathematics (1996 through 2017), reading (1998 through 2017), and civics (1998 through 2014) assessments. It examines both overall trends and gaps by race, ethnicity, and family income.

- Chapter 2 examines state policy related to civics education. It describes findings from a 50-state inventory of high school course requirements, K-12 social studies standards, and curriculum frameworks. The analysis is motivated by questions about the alignment between current state requirements for civics education and the practices believed by experts to constitute a high-quality civics education.

- Chapter 3 provides a look at the nation’s social studies teachers. It presents statistics on the demographics, qualifications, responsibilities, compensation, and satisfaction of social studies teachers in secondary grades. Through comparisons with math, English language arts, and science teachers, this section shows the ways in which social studies teachers are—and are not—notably different from teachers of other subjects.

Taken together, these chapters provide a portrait of civics education in the United States. They describe the performance of U.S. students in civics education, insofar as we can observe it, while using state policies, teacher characteristics, and student survey results as windows into students’ experiences.

Are schools equipping students with the tools to become engaged, informed, and compassionate citizens? Are they equipping some students, or groups of students, better than others?

Of course, the resulting portrait is incomplete. Some of the report’s limitations are our own, or reflect the nature of writing a single report on a broad, complicated topic. Other limitations, however, reflect the relative under-emphasis of civics education in the United States. Consider, for example, that the first administration of the NAEP (a trial administration in 1969) measured students’ performance in three subjects—citizenship, science, and writing—yet a lack of funding and political will have made the NAEP civics assessment sporadic in its administration and, in recent years, confined to eighth grade.

We hope this report will add to a growing chorus of voices arguing that education policy and practice in the United States should place greater emphasis on schools’ role in supporting and strengthening American democracy through how it educates its students.

Acknowledgements

This report was made possible by the generous financial support of The Brown Foundation, Inc., Houston. The authors would also like to thank Tom Loveless for his many contributions to the Brown Center on Education Policy, which includes authoring prior editions of the BCR and offering comments on a portion of this edition. In addition, we are grateful to Elizabeth Sablich and Louis Serino for editorial support, Sarah Andes and Dana Harris for comments and insights, and Caitlin Dermody, Bethany Kirkpatrick, James McIntyre, Maximiliano Rombado, and Kimberly Truong for research assistance.

Read the next section of the 2018 Brown Center Report, or visit the full report page.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).