California’s Road to Climate Progress aims to answer a central question: Even with multiple laws and focused rulemaking, why has California struggled to reduce driving distances and increase infill development? The first piece explained California’s goals, the transportation and land use policies set up to meet them, and the structural issues with the current approach. The second piece explored the state’s current legal and programmatic regime in greater detail, while the third piece examined the local view of the state’s regime. This piece introduces principles that could guide the next wave of state reforms and is accompanied by a policy playbook for interested decisionmakers.

Introduction

For two decades, California has functioned like a living laboratory when it comes to reducing driving distances and promoting infill development. No other state has come close to passing as purposeful of laws, including the Sustainable Communities Strategies (SCS) mandated by SB 375 and the switch to vehicle miles traveled (VMT) standards within SB 743. As those laws and others became administrative rules, lawmakers had a chance to witness how local governments and private developers responded.

Like any policy implementation at this scale, performance is mixed. Many of the laws and policies aren’t working as intended, both for the state lawmakers who crafted statewide policies and the local officials and developers who feel their effects. Other laws and policies reveal how state programs can elicit the kind of market-driven responses lawmakers want. It’s now up to California’s leaders to use the lessons they’ve learned over 20 years and adjust accordingly.

This opportunity comes at a pivotal moment. In barely more than a year from now, a new governor and incoming class of legislators will arrive in Sacramento. Many of these policymakers will be new to their office, with every reason to take a forward-looking approach while learning from their predecessors. And for current leaders leaving office who publicly support changing California’s land use, this may be their final shot to adjust the state’s course.

If current and future state leaders are ready to consider the next wave of transportation and land use policies, we recommend building those reforms around certain core principles. These leaders should be realistic about what kinds of behaviors consumers can actually change. They should be respectful of the limited time local officials have to comply with state requirements by avoiding requirements that don’t result in desired outcomes. And they should be laser-focused on delivering public and private capital to the places best able to support low-VMT travel.

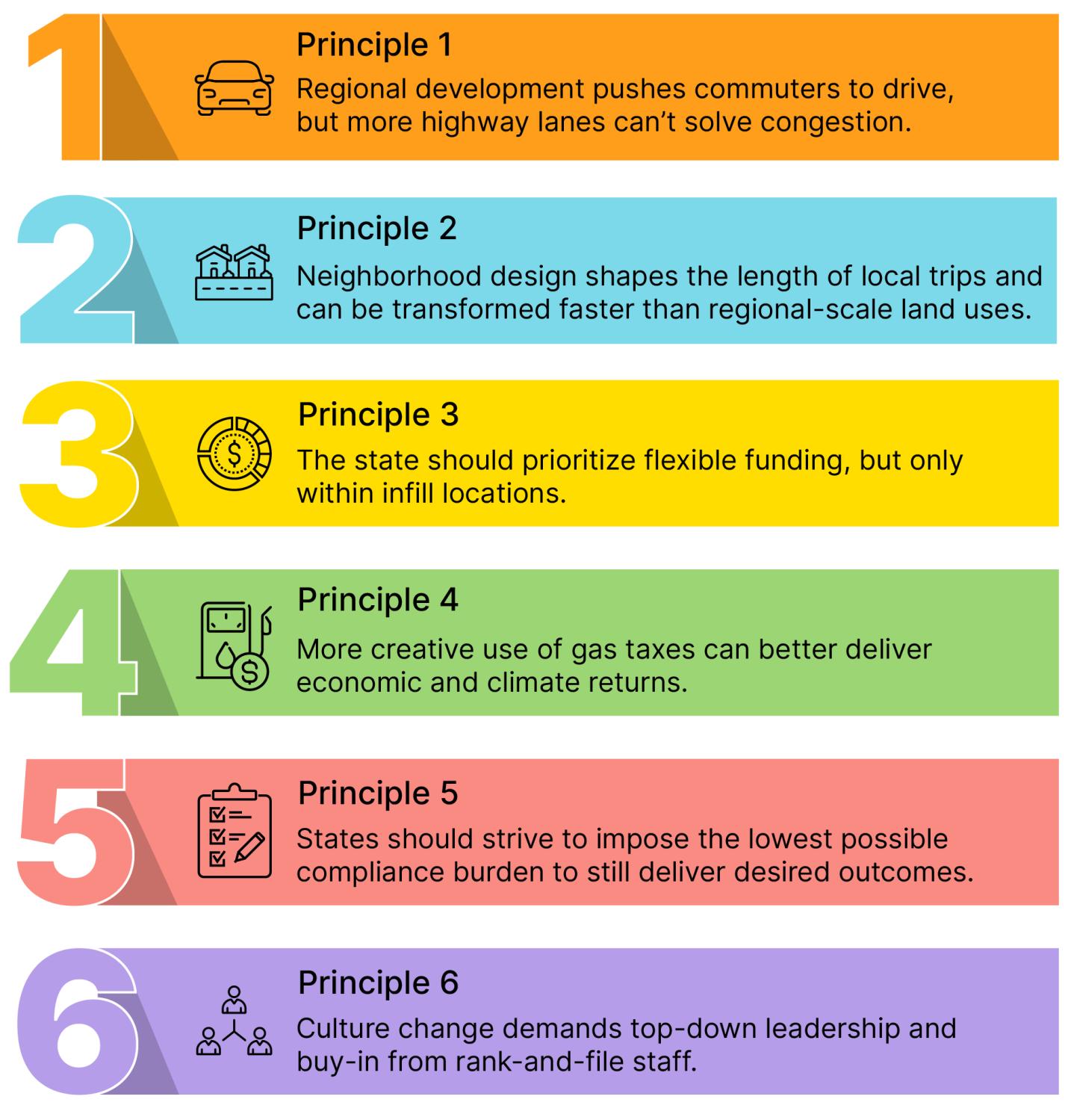

This report outlines six core principles that summarize the crucial lessons of the last two decades, around which current and future lawmakers should orient their reforms. Respecting these principles would go a long way to making the next wave of state transportation and land use laws deliver more sustainable, resilient, and affordable communities for decades to come. They are:

California laws and policies we assume will not change

There’s plenty of room for policy reform in California. However, some laws are unlikely to change simply to achieve transportation-related goals. When designing the six principles in this report, we considered the following issues off-limits.

First, local governments will retain current land use authorities. Since the state’s inception, California’s cities and counties have written their own zoning code, created standards for all manner of urban amenities, and approved local building permits. That autonomy has allowed them to address both local and statewide issues in a manner appropriate to their unique circumstances. In an effort to address the lack of homebuilding in California, recent state laws such as AB 130 and SB 79 preempt that authority in certain cases. Across most locations and in most instances, however, local governments are still in control of how their land is developed.

Second, we assume Proposition 13 and Proposition 218 will not be repealed or otherwise overturned. Proposition 13 gave the state legislature final say over property tax increases, while Proposition 218 required most tax increases to be voted on before going into effect. Legitimate critiques of these measures exist, and their effects have not been uniformly or even generally positive. Even so, in-state experts said that reforming Prop 13 and 218 is politically infeasible.1

Third, transportation revenues will stay in the lockbox. In 2017, the state Constitution was amended following the passage of the SB 1 transportation funding bill. That amendment resulted in Article XIX, which requires transportation revenues to be used for transportation-related expenditures. This affords the state some wiggle room, primarily its ability to direct transportation funds to affordable housing and other land development activities when its express purpose is to mitigate environmental harm (e.g. induced VMT) as disclosed through the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Experts were clear that undoing the lockbox would be infeasible, but they are more sanguine about the possibility of adding qualified expenses (i.e., broadening what counts as a “transportation-related expenditure”).2

Principle 1: Regional development pushes commuters to drive, but more highway lanes can’t solve congestion.

Like most states, California went beyond just the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System when it built out its highway network. Those new roads coincided with and incentivized a kind of land development that prioritized single-family housing and scattered job hubs where zoning allowed.

One certainty of a land use model like that—whether in California or elsewhere—is the large geographic footprint that follows. The state’s highway network and all that nearby developed land result in longer driving distances; workers consider jobs spread across their metropolitan area and even neighboring regions, families lives further from daycare and school, and everyone travels a little longer to get to parks and restaurants.

California can’t simply unwind all that development. From the houses, offices, and industrial buildings to the highways that connect them, the state is now stuck with expansive regions and their current bias toward private vehicles. The distances are too long, and too few people are starting or ending in the same places for transit or bicycling to offer competitive travel times. It’s no wonder Californians feel like they have no choice but to drive, especially for those who relocate far from their jobs and other key activities in pursuit of affordable housing.

With so many people driving (especially families with school-age children and workers during rush hour), frequent congestion on the state’s metropolitan freeways is practically inevitable.3 There is simply no amount of new lane miles that can relieve all that traffic—not least because new lane miles almost inevitably induce so much travel that the bigger roadway congests again. Of course, the state knows they can’t build their way to smooth travel, but for many legislators and officials, the tantalizing prospect of adding a few lane miles to just one more freeway in someone else’s backyard remains.

State officials should heed their own advice and not add new lane mileage. Not only will those new lanes not solve congestion, they will add long-term liabilities to state and municipal budgets and expose nearby communities to a host of negative externalities. Even concerns about the flow of freight should be critically examined, where reducing household vehicle use could more affordably free space for freight traffic.

If state leaders want to get serious about reducing roadway congestion on highways or in the busiest activity centers, then road user charges (RUCs) are the best route. Global evidence consistently finds that road pricing shifts travel demand and reduces congestion, with New York’s early results confirming American drivers are no different than their global peers. Constituents also like the decreased traffic, leading to greater political support than some elected officials may initially assume.

Principle 2: Neighborhood design shapes the length of local trips and can be transformed faster than regional-scale land uses

Commutes may be the most important journey many people take each day, but they represent less than a fifth of all trips.4 Households spend far more time and drive much more when shopping for groceries, running errands, going to school, and socializing. Critically, these trips are more sensitive to neighborhood design than commutes. Researchers consistently find that the relative proximity and connectivity between locations significantly impact people’s trip distances.

This matters because it’s far more possible to change a neighborhood’s built environment than the region-scale conditions that shape commutes. Adding more homes, businesses, and civic amenities within one neighborhood can shorten trips in relatively little time. Those effects can also compound, as locating more people and destinations in networks of adjacent neighborhoods creates a virtuous cycle of greater demand to travel within those areas.

Once neighborhood design shifts—including more residents living closer to where they shop, eat, and play—transportation improvements have an even greater impact on VMT. It’s easy to assume that the “if you build it, they will come” axiom applies to transit and active transportation intervention, but the reality is more complicated. Enough residents and destinations must surround those new stations and bike lanes for them to get used. Put simply, increasing even “gentle density” in neighborhoods and prioritizing human-scale design create greater demand for transit and active transportation, and generally reduces VMT.

How other places have attempted to reduce vehicle miles traveled—and who’s accomplished the goal

Achieving lasting reductions in VMT has been one of the most challenging goals in American public policy. The rigidity of community designs, housing stock, and transportation assets creates a kind of vehicle lock-in where people feel like they have no choice but to drive. However, there are emerging models of planning and investment that can meaningfully reduce VMT. States and cities have taken novel approaches to tie funding to this issue, and some have seen a real decline in VMT as a result.

The most encouraging results come from places that fundamentally rebuilt neighborhoods and their transportation connectivity. From 1996 to 2014, Arlington, Va., welcomed 50,000 new residents into relatively dense housing built along the area’s new heavy rail transit line; traffic counts on many urban streets declined over roughly the same period. Similarly, before a light rail connection between Portland and Hillsboro, Ore., was opened in 1998, the latter town let developers write new zoning regulations—and the area densified. Now, Hillsboro boasts non-auto mode shares far beyond regional averages.

More recently, states are experimenting with direct fiscal incentives to promote specific land uses. In Massachusetts, Section 3A of the Zoning Act requires municipalities served by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority to rezone to allow multifamily housing in specific locations. Communities that don’t comply are ineligible for certain funding streams. Likewise, to reach a state-defined housing production goal, counties and municipalities in Colorado with a certain amount of transit acreage must create transit centers—areas with dense residential or mixed-use zoning. If the state certifies that they’ve rezoned enough area to reach their goal, localities become eligible for both a grant program and tax credit. Across three Colorado laws related to housing production, this one reported the highest rate of compliance.

Principle 3: Infill locations need flexible funding to accelerate real estate development

California’s leaders must act with urgency and precision to make good on their commitment to reducing VMT. State officials and staff should invest in the right assets in the places best suited to support shorter trip lengths. That requires two steps. First, California’s Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and the California Transportation Commission (CTC) must stop investing in roadway capacity expansion projects that enable low-density and wildfire-prone land development. Second, California should put its transportation revenue to the best immediate use: supporting infill development by densifying and transforming neighborhood characteristics in areas where the most people will be served.

California will immediately realize savings by ceasing investment in new roadways—and should invest those newly freed-up funds, as well as others, in projects that subsidize and support infill development, all while maintaining spending on roadway maintenance and operations. California’s transportation decisionmakers should not limit themselves to traditional roadway or transit projects, either—or transportation projects generally. The state should prioritize spending these funds on projects that improve supportive infrastructure in low-VMT areas, such as upgrading a water main that connects to a new apartment building, breaking ground on a new park, and physically redesigning local roadways to improve multimodality. Though not every such project is an eligible transportation expense under Article XIX, they should qualify if they will help reduce VMT, which is one of the state’s most desired transportation-related outcomes.

The state’s new VMT mitigation bank demonstrates a path forward.5 It confirms the state can channel revenues to infill locations for flexible needs, and its fee collection mechanism should stymie VMT-inducing projects. However, the mitigation bank alone won’t reduce VMT enough.6 The bank is only capitalized when a project that would induce VMT is undertaken, and only at an amount commensurate to that potential VMT. That means that if a VMT-inducing project goes forward, the fees its sponsors pay will, at most, mitigate the VMT the project would cause, making a net-zero VMT impact the best possible outcome. In the best-case scenarios for its supporters, the mitigation bank will stop VMT-inducing projects because developers would abandon them due to higher costs. But in that case, too, the money dries up and leaves the state with no additional funds to underwrite VMT-reducing projects.

The state should think wider, focusing on funds beyond those the mitigation bank will deliver. Using existing transportation revenue flexibly on various infill infrastructure projects can support lower VMT and is in line with national best practices. If the 20th century saw the state purposely build connections to an ever-growing urban fringe, this century’s lawmakers should purposely invest in infill areas.

Principle 4: More creative use of gas taxes can better deliver economic and climate returns

California isn’t using its transportation funds to their full potential. Instead, it invests the clear majority of funds exclusively in roadway assets. That focus is shortsighted and narrow-minded. Roads are liabilities; they cost considerable money to build, and even more to maintain. Time and time again, research has affirmed that highway investments are no longer correlated with increases in aggregate economic activity.7

The sheer scale of California’s transportation funds puts their underutilization into full perspective. Fiscal Year 2025 alone saw total state revenue from motor vehicle taxes and fees top $20 billion. In the state’s recently enacted budget, transportation agencies are only outspent by those in charge of health and education. That kind of capital can be a powerful catalytic force if used correctly. Not only does Caltrans have billions of dollars at its disposal, but California also has a good bond rating and stable fiscal outlook. And gas taxes are just another excise tax—there’s nothing predetermined about spending them on roadways, and the state should be thoughtful in how to best use its funds to achieve the goals it sets for its transportation network.

The California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA) and its subordinate agencies could use those funds to promote redevelopment. It could leverage its dollars to support the development of infill infrastructure, capturing tax revenue from the new development. Whatever creative way legislators come up with to use the state’s transportation revenue, there’s more than enough money to get them started.

Once lawmakers have settled on how to flexibly use transportation revenues, it’s incumbent on CalSTA to direct its subordinate agencies on how to do so equitably. The question of where to invest will be paramount. Of course, regions with higher levels of density have more complex approaches to developing their land, while sprawling areas will likely take a different tact. Sensitivity to existing neighborhood contexts will be crucial, and even supporting gentle density through less dense development can reduce VMT.8

New ways to use transportation funds

It’s up to California’s leaders to reimagine where, how, and on what to use their transportation revenues. Fortunately, there are domestic and international examples of governments that have leveraged their transportation dollars in different ways. State leaders can look to these places as they draft their own reforms.

Even with its transportation revenues in a lockbox, Maryland has supported transit-oriented development (TOD) through its Transit-Oriented Development Capital Grant and Revolving Loan Fund. This loan fund distributes transportation revenues to capital and planning efforts meant to enhance development around existing transit stations.

A bit further away, Japan and Australia had versions of the same debate over how transportation funds should be spent. In 2009, Japan decided that its growing transportation revenue was leading them to fund unnecessary roadway infrastructure; now, those dollars are completely free and counted among the country’s general funds. Since Australia loosened its restrictions on transportation dollars, its government has announced hundreds of millions of dollars to develop homes and parks in TOD precincts.

Principle 5: The state should strive to impose the lowest possible compliance burden to still deliver desired outcomes

Local and regional governments will always be partners with the state in lowering VMT. Right now, though, officials must undertake onerous processes that can be easily manipulated to produce compliant plans but limited results. Even localities that try to achieve state-set goals are still often left with lengthy documents and little progress. Worst of all, those governments’ staff are taxed beyond their capacity. Without sufficient resources to meet state demands, they often shirk training permanent staff and opt for short-term fixes with consultants. As reforms to the state’s system are proposed, legislators should remember: Demands for local compliance should match local capacity.

State legislators should take two crucial steps. First, they should make the state’s regulatory regime less burdensome. That will likely include both unraveling some of the complexity of the current legal framework and ensuring that new laws don’t increase compliance costs. In the pursuit of reducing VMT and environmental risks, state decisionmakers should solicit feedback from local and regional officials to design more streamlined planning and compliance laws, as long as they are equally or more capable of hitting climate and VMT targets.

Second, lawmakers should provide funding to cover the administrative costs of complying with the state’s legal regime—whether new laws are passed or old ones amended or rescinded. Not only will that funding act as a carrot to ensure local and regional governments comply with state requirements, but that kind of fiscal support will also only make those requirements more politically palatable to the entities and the associations that represent them. Critically, and per the first step, the state must resist increasing compliance alongside funding levels. If they do, officials we spoke to worried that the new funding would have to be spent on consultants to maintain compliance instead of building enduring staff capacity.

On the margins, state agencies can do more to set localities up for success. At the very least, these agencies should issue timely and clear guidance to accompany all new laws with which localities must comply. The state can also be more proactive by facilitating peer learning through a repository of successful practices from cities, counties, and regions on public engagement, financing development, transportation planning, project design, and more.

Principle 6: Culture change demands top-down leadership and buy-in from rank-and-file staff

Caltrans was conceived to build roads. And throughout the 20th century, delivering on that core purpose was a boon to the state. But while expanding California’s roadway network led to an explosion of new homes, it destroyed others. Though connecting some residents and businesses increased aggregate economic productivity, it permanently displaced many communities of color at the same time. Still, without its roads and the agency that built them, California would never have grown into the fourth-largest economy in the world.

Last century’s core purpose, though, is no longer aligned with the state’s current long-term goals. With interregional connectivity complete, lawmakers are understandably turning their attention toward household affordability, environmental justice to write Caltrans’ historical wrongs, climate resilience interventions, and long-term stewardship of the state’s treasured natural environment through climate mitigation. Delivering on that wider vision requires staff up and down Caltrans’ organizational chart to execute old tasks in new ways. Simply put: Caltrans must change what has been core to its work for a century.9

Change like that doesn’t come easy. Previous research has shown that Caltrans employees’ skills and how they’re organized in the department are misaligned with the state’s climate goals.10 A reorientation of departmental culture away from roadway building and toward VMT reduction will require an enormous effort by upper and middle management as well as significant buy-in from rank-and-file staff.

We recommend adopting techniques that prioritize teaching—not telling—staff the benefits of the new goals the legislature has embedded in law. Whether for engineers, planners, project managers, or administrative leaders, Caltrans can use its orientation period for new staff and require periods of professional development for current staff to demonstrate firsthand the value of infill-focused projects. That might mean site tours to a Main Street that’s been revitalized by the addition of bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, or showing the hazards wildfire-prone communities face. It can include applied accounting classes that compare costs and returns from different project types. It can be peer exchanges with colleagues in the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), the Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation, local utilities, and private developers. For leadership’s part, acting with strength and conviction by halting roadway-widening projects and diverting the revenue will strongly signal a new direction for Caltrans.

The need for that kind of cultural change may be best documented and most obvious at Caltrans, but other state agencies need the same. Multiple experts told us that the California Air Resources Board was far too focused on the technocracy of greenhouse gas measurement and modeling than actually achieving targeted reductions. A recent San Francisco Chronicle article argued housing in California is detached from economics, noting HCD has no staff economists. Even further, some experts argued the CTC and the California Coastal Commission may be more focused on applying their own rules and preserving their own power than achieving statewide goals.

Without a state workforce both willing and eager to act, the impact of even the best state law will be muted. Bold efforts should excite well-intentioned staff about a new vision for their departments.

Where has cultural change spurred transportation policy forward?

California isn’t the only state attempting to fundamentally shift culture within its department of transportation (DOT). Research on state DOTs has shown that their cultures and workforces are often ill-suited to tackling contemporary challenges. Some states have worked within the bounds of workforces that are mostly comprised of engineers and builders by encouraging experimentation with active transportation solutions. Other states have changed how they interview and hire to recruit younger, sustainability-focused staff.

The shifts abroad have been much more pronounced—and offer successful examples of a path forward. The Rijkswaterstaat, the agency responsible for managing and building road and water infrastructure in the Netherlands, is a particularly instructive example. Beginning in the mid-1800s, the Rijkswaterstaat became dominated by civil engineering approaches. The monumental public works projects those engineers delivered were heralded by the public until 1970, when environmentalists and elected officials began to see those megaprojects differently. In response to shifting views, the agency changed. It hired biologists and ecologists, and, most importantly, it framed new environmental concerns through an engineering lens. Though its priorities and interventions increasingly centered on environmental concerns, the agency continued to prioritize an engineered approach to solving problems.

Conclusion

Embodying these six principles would be a fundamental shift in how California plans for transportation and invests its significant revenues. It would mean acknowledging the kind of projects and places best suited to reduce VMT, and directing big, flexible sums of money there. It would revitalize the state’s relationship with local governments and offer a bold vision to energize agency staff. And it’s all based on the goals policymakers have expressed in law, executive action, and their public commentary. These principles are an affirmative approach for state leaders to deliver the resilient, clean, affordable future they sincerely want.

To help put these principles into practice, we prepared a playbook of policy interventions as a companion to this article. From a completely new funding regime to enhanced workforce education, policymakers in Sacramento have at their fingertips the tools to make good on their climate ambitions.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This research series was greatly supported by colleagues at the Policy and Innovation Center. The authors would like to sincerely thank them for their time spent as thought partners and facilitating understanding of the local perspective on these issues. Their partnership made this work possible. The authors are grateful to those who provided thoughtful critiques of and comments on this report, including Manann Donoghoe, Zack Subin, Jeanie Ward-Waller, Egon Terplan, Jacob Armstrong, Mark Slovick, and many others. The authors would especially like to extend their gratitude to the 27 external experts who were interviewed for this project. The authors thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Carie Muscatello for web design, and the rest of the Brookings Metro communications team for their support. The authors are solely responsible for all remaining errors and omissions.

The Brookings Institution would like to thank the San Diego Foundation for its generous support of this research. Brookings Metro is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Brookings Institution and its donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- Source: Brookings’ expert interviews.

- Source: Brookings’ expert interviews.

- The existence of congestion isn’t altogether bad; evidence of so many people and goods simultaneously moving around is generally a sign of a healthy economy. Instead, the concern is the external costs created by vehicular congestion, especially when there aren’t viable alternatives to driving.

- According to 2025 research by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, commutes accounted for less than 30% of VMT in San Francisco and Palo Alto.

- Metropolitan regions are also setting up their own VMT mitigation banks, which can include various qualified project types to receive public funds. See one example from the Western Riverside Council of Governments.

- Some experts questioned whether the state’s new VMT mitigation bank will reduce VMT at all. One official argued that it may actually lead to more VMT-inducing projects by permitting such projects as long as they’re accompanied by mitigation measures, which may be less effective in reducing VMT than project proponents claim.

- More recent research suggests that increasing transportation infrastructure investment writ large alone will not lead to economic growth.

- For one example, a 2017 article by Jinhyun Hong at the University of Glasgow found that the effects of gentle density on reducing transportation emissions may be even more pronounced than the most dense neighborhoods. Another is a 2019 article by Marlon G. Boarnet and Xize Wang, which found inner–ring suburban developments can often achieve the greatest relative VMT reductions. Finally, 2023 California-based research by Susan Handy, Amy Lee, and others found promising results in multiple locations.

- Beyond Caltrans, many experts articulated analogous needs for cultural changes in other relevant state agencies such as HCD, the California Air Resources Board, and the California Coastal Commission. Cultural changes at these agencies may help California achieve its climate-related transportation goals, but our research primarily focused on the operational culture of Caltrans.

- During our research and in our expert interviews, we primarily heard there was a need for Caltrans leadership to fully dedicate themselves to climate goals and for rank-and-file staff to prioritize climate-benefitting solutions to transportation needs. The cited report articulates a need for organizational change within Caltrans, which may be a complementary strategy toward reorienting the agency to achieve its climate-related targets.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).